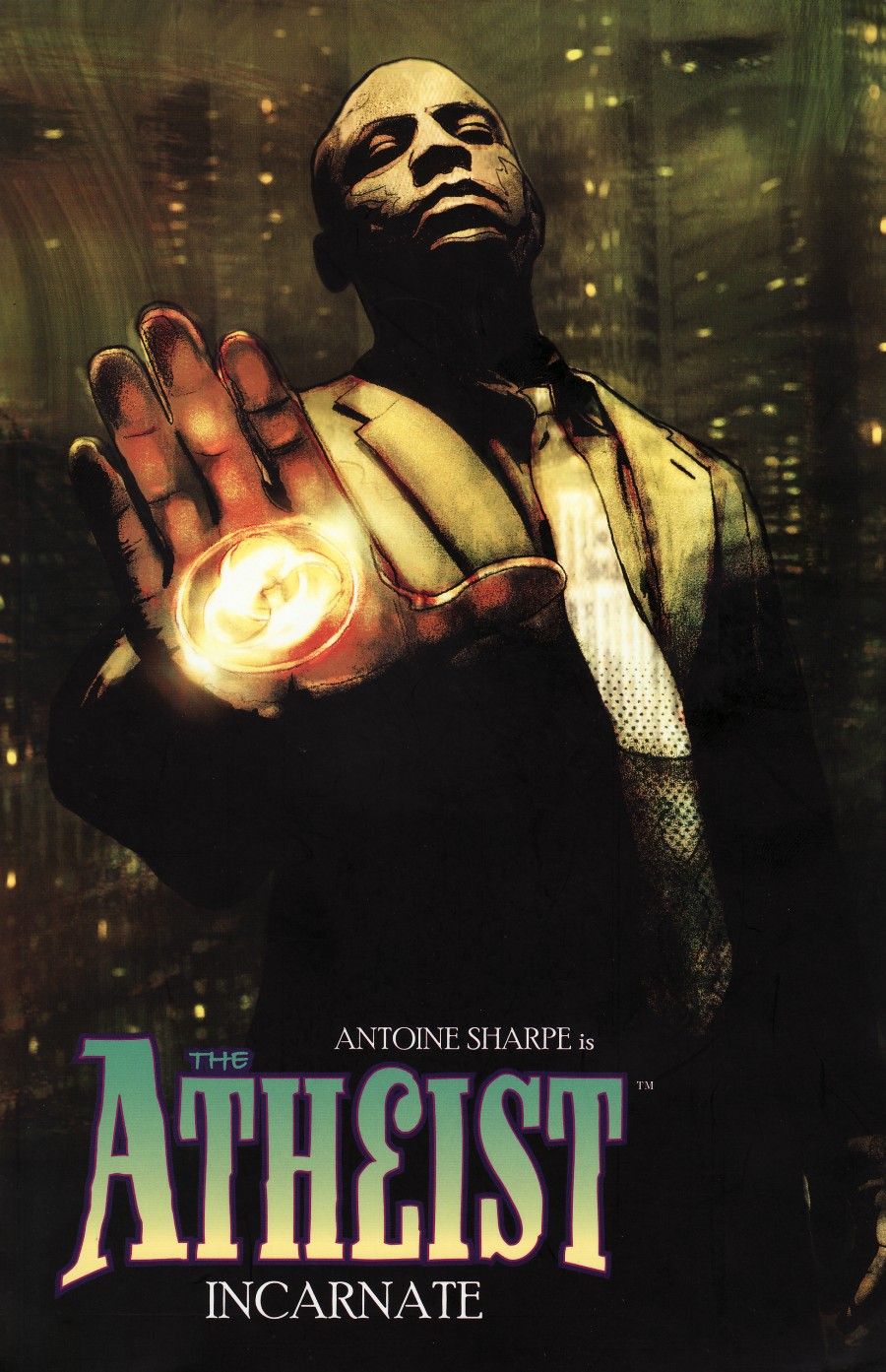

The Atheist, Volume 1: Incarnate

Written by Phil Hester; Illustrated by John McCrea and Will Volley

Desperado; $15.99

I had dinner recently with someone and I mentioned that I was reading The Atheist. "Oh, yeah," he said. "There was some controversy about that title, wasn't there?" I don't remember the controversy itself, but I do remember an interview or something in which Phil Hester felt the need to explain the name of his book. He does it again in the introduction to the collected volume. What's surprising, I think, is that it's not conservative religious people who were complaining this time.

Hester writes, "I thought The Atheist was a snappy, if somewhat jarring, hook of a title. It seemed to perfectly describe Mr. Sharpe's uncompromising brand of skeptical thinking and just plain old sounded cool. Of course, I should have considered that this title might cause readers to infer the book would have some stance, pro or con, on the atheist world view, and that some atheists would take offense at their views being fodder for a horror comic book." He also says that he's dropping the title on any potential future volumes.

I bring this up because I remember being jarred by the title when the first issue came out. I remember wondering whether the book would take a stance on atheism and whether it would be pro or con. This was one of the first books I read where Hester was writing but not illustrating it, so I didn't know what to expect. But I also remember reading it and being relieved that atheism really wasn't what the book was about at all.

It's not that Hester skirts the issue. He doesn't even acknowledge that it is an issue. The main character in The Atheist is an atheist, and that affects how he reacts to events in the story, but there's no controversy about it. There's no debate. That's not what interests Hester. What interests him is telling a good story, which is awesome because I'm also much more interested in reading one of those than I am an essay on belief.

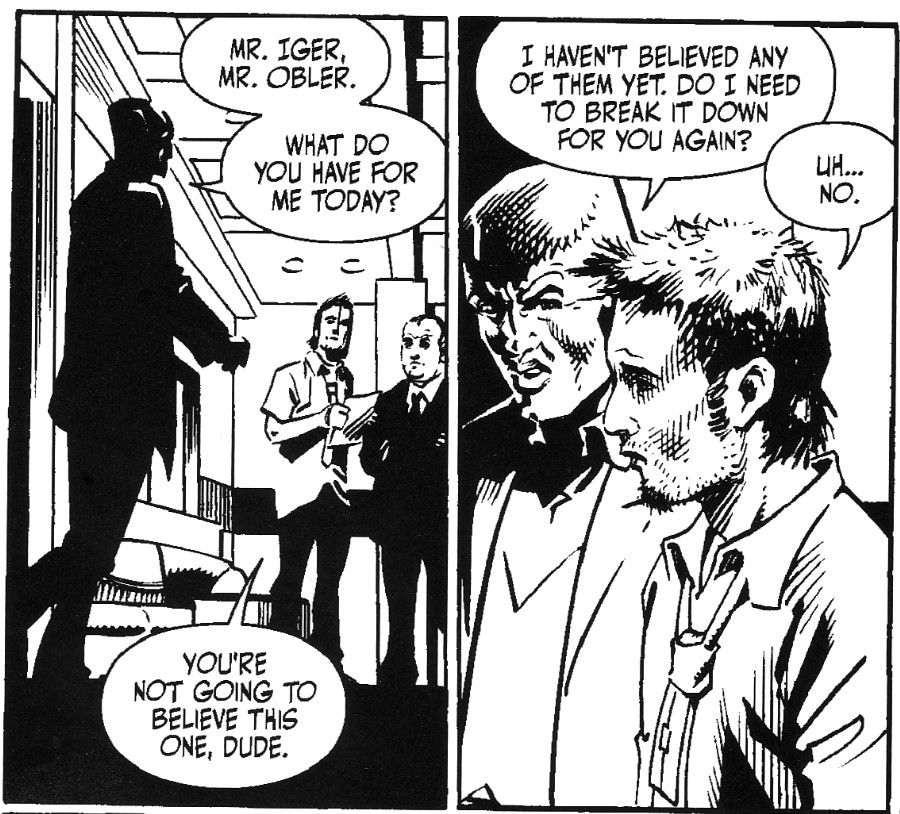

Antoine Sharpe is a freelance agent who specializes in solving cases that normal government agencies snicker at. Got a Bigfoot or Chupacabra sighting near a murder scene? Ghosts on government property or psychic terrorists? You bring in Sharpe to figure out what's really going on and put a stop to it. As Hester says in the intro, in addition to being a brilliant investigator, Sharpe is also an uncompromising skeptic and that allows him to see past all the distracting, supposedly supernatural details to the real problem. It also makes him somewhat infuriating to work with; not just because he refuses to accept anything at face value, but also because he's right most of the time.

You can't have a skeptical government agent investigating supernatural cases without inviting comparisons to Dana Scully, but I'm not sure that that's a comparison to back away from. The Atheist may have some similarities to The X-Files, but it's no rip-off. For one thing, "rip-off" implies that something's inferior to the original work. The story in this volume is equal to the best of The X-Files' standalone episodes. If you like The X-Files, you can be sure of enjoying The Atheist as well without fear of disappointment.

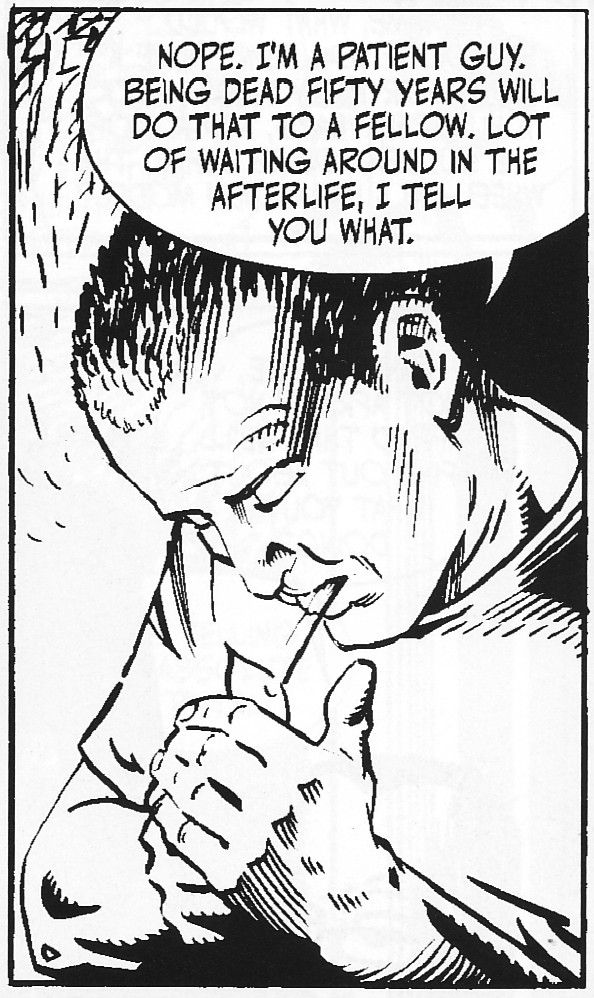

The story in this volume has Sharpe investigating what appears to be possession of bodies by spirits from the afterlife. A wide variety of people - but mostly teens - are all leaving home and moving to Winnipeg where they're living on the street and claming to be dead people. There's even some evidence that seems to support their claim. They're speaking in languages they have no way of understanding and possess intimate knowledge of the deceased individuals they're claiming to be. Sharpe thinks it must be a remarkable, new mental illness if not an outright hoax or a new religion.

Hester does a great job of bringing Sharpe to life. He can be completely ruthless in his investigation - including threatening an innocent man with his daughter's safety in order to get information - but is extremely compassionate towards a scientist friend who's body is systematically being replaced by intelligent cancer cells. "His body is hideous," Sharpe warns the Canadian Intelligence agent he's working with, "but he's the most beautiful person you'll ever meet." Later he reveals that he's a bit autistic, reads at the pace of a first grader, and can only stomach wearing yellow and white clothing, but can figure out the age and gender of an author by looking at a single printed page. He's got other quirks as well, but none of them are distracting or laughable. They round out the character without turning him into a cartoon.

The art goes a long way towards this as well. This volume collects four issues; three of which were illustrated by John McCrea and the fourth by Will Volley. And though they have slightly different interpretations of the characters (McCrea's Sharpe is more chiseled and rugged than Volleys, for example) Volley perfectly mimics the realism of McCrea's issues. There's no confusion about which character Volley's showing you and issue three flows smoothly into issue four with very little to slow you down. The whole book feels very grounded and truthful which makes Sharpe's perspective more believable and the danger more serious. The action is exciting and scary. There's a showdown between a snowplow and a car that had me cringing and bracing myself for impact.

The book is full of intentional contradictions, whether between reality and fantasy or simply within Sharpe's nature as a human being. I said earlier that Hester didn't intend to discuss atheism as a world view, but that certainly doesn't mean that he's not asking readers to think. He doesn't explain away or simplify the incongruities in Sharpe's character; he shines a giant spotlight on them and makes you deal with them. And he does it in such an honest way that he humanizes his main character at the same time that he's forcing you to examine your own inconsistencies.

Four out of five mutant scientists.