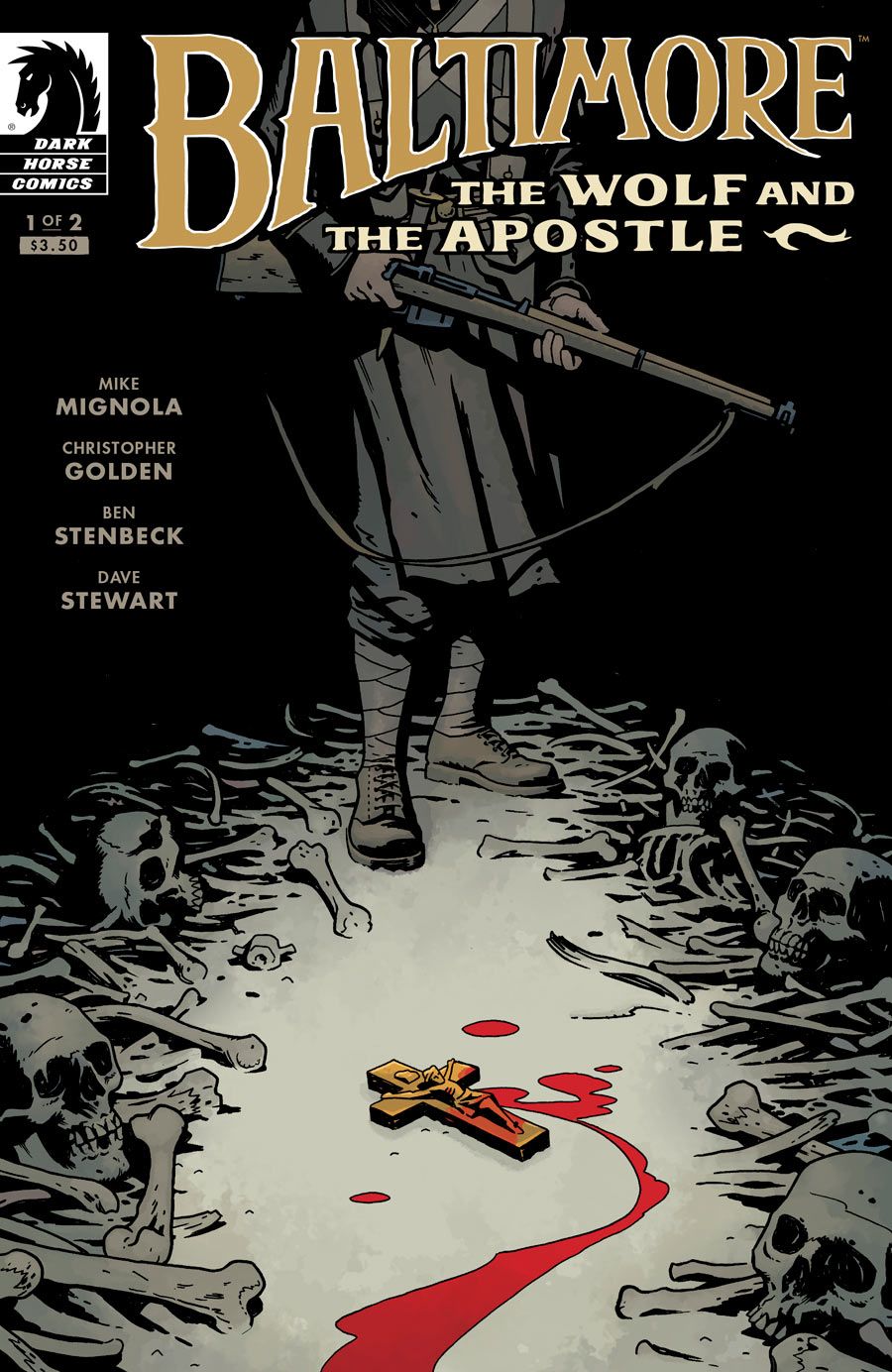

While "Baltimore: The Wolf & The Apostle" serves as artist Ben Stenbeck's swan song on the character's adventures, "Baltimore" co-writer Christopher Golden stresses to CBR News that this two-issue story also provides a great jump-on point for new readers.

Golden characterizes the tale as a "quick and nasty" chronicle of an insane werewolf wreaking havoc and harm throughout an abandoned castle, set amidst an (alternate timeline) broken and desolate post-World War I Europe -- decimated plague and vampirism. In this adventure, Judge Rigo's involvement allows Golden and "Baltimore" collaborator/creator Mike Mignola to offer a different perspective on Lord Baltimore through the pair's interactions, while allowing Stenbeck a chance to portray the judge on page and set the character's look for his artistic successor, Peter Bergting.

Baltimore: The Wolf & The Apostle" arrives in stores tomorrow, October 29, from Dark Horse Comics, but we have an exclusive preview of the first issue right here!

CBR News: "Baltimore: The Wolf & The Apostle" is artist Ben Stenbeck's final work (for now) in the Baltimore universe. How important has Stenbeck been to the look and vibe of Baltimore?

Christopher Golden: Ben made the book work, really. Baltimore is a man who was in the wrong place at the wrong time, an ordinary British soldier who encountered a monster on the battlefield during World War I, which led to his entire family being murdered. He's not just a monster hunter -- he's doomed. Damned. An engine of vengeance and a pawn of higher powers. He may not even be human anymore. When he finally got his revenge, he learned that his mission was far from over and now we're learning that there is a dark power behind it all and he's going to have to face that. To pull that off in the settings we've chosen, cities and villages all across plague-ridden, war-ravaged Europe, you need an artist who can give texture and grit and a sense of tangible reality to that world, someone who can really help the reader engage and feel. Ben does all of that. He gave it all weight.

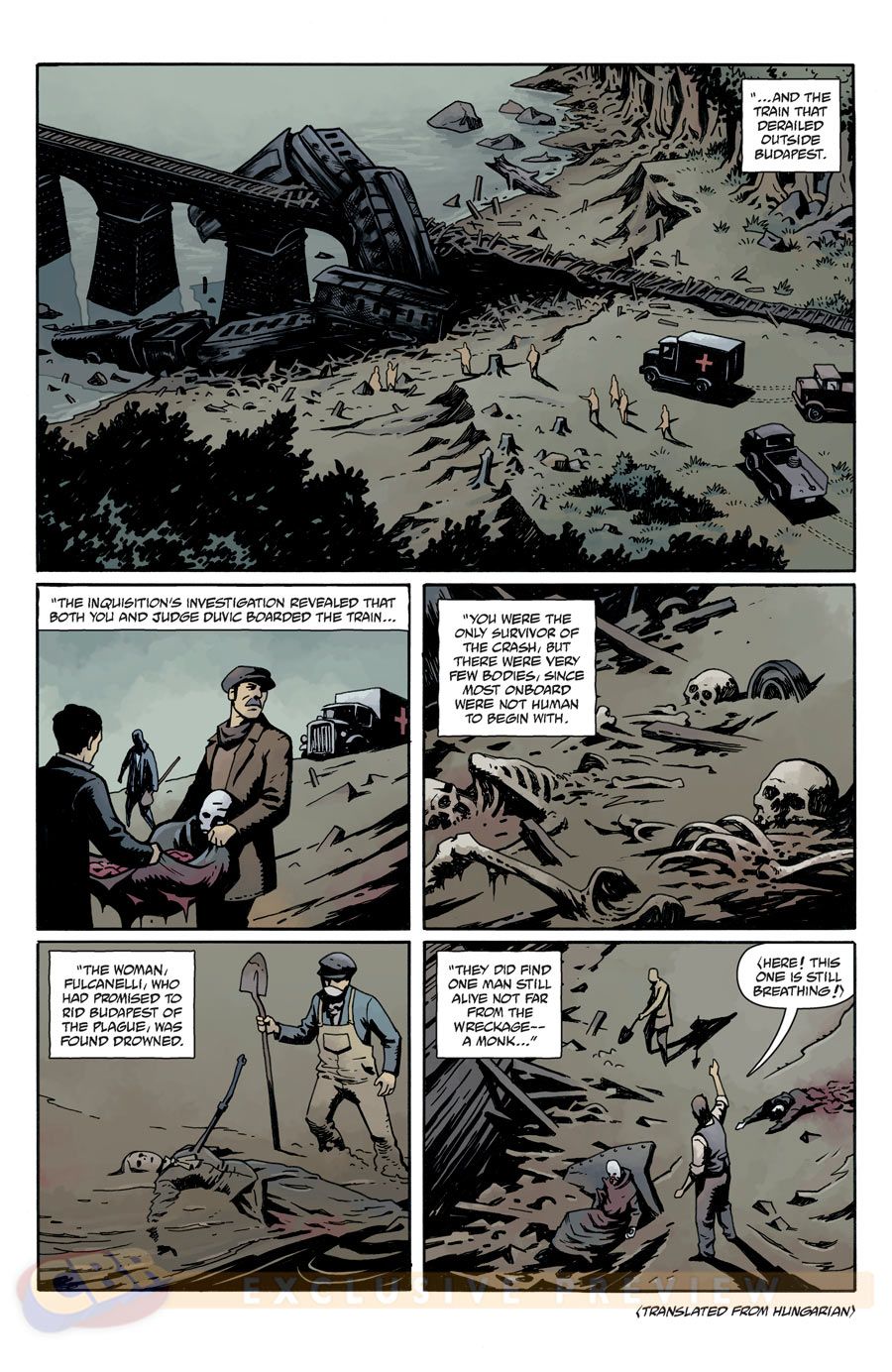

When we were looking for a new artist, we knew two things -- that we didn't want a clone of Ben, and that we wanted someone who could accomplish the same things, but in his own way. Peter Bergting has really come into his own with the Baltimore work he's done so far. With "The Wolf and the Apostle," knowing it would be Ben's last stint on the title, we wanted to let him play. He was instrumental in Judge Duvic coming to life and had done such a great job of turning Duvic into a werewolf, but had only been able to draw the wolf on a few panels. I knew I was going to revisit Duvic and it only made sense that this story be Stenbeck's swan song. The most fascinating thing, though, is that while it's Ben's last story, it's the absolutely perfect story for a new reader to jump on. It's self-contained in the sense that you're getting the story of a new character, Judge Rigo, so you're meeting him at the same time as the rest of the readership, but you're also getting a glimpse of Baltimore and learning about him through his interactions with Rigo. We didn't set out to do this two-parter as a "starting point," but it really is a great place for those who have not read Baltimore before to give it a try.

"Baltimore: Wolf & Apostle" is set in a very different kind of post-World War I era. As a storyteller who clearly has a love of history, what do you most relish about tackling a story in this era?

I did a double major in college, English and History. My history major had a concentration in European history, but I've always been intrigued by European and American history in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. "Baltimore" is set in an alternate timeline, where plague and vampirism basically stopped the war in its tracks, but otherwise the world has marched on. It's such a weird time in history -- a time when most of what we think as modern conveniences had been invented but were only slowly coming into common usage, including cars and airplanes, the subway and the telephone. Yet, in the stories we're telling, there's still something raw and untamed about the world. People are more likely to travel by ship -- or the occasional zeppelin -- than by plane.

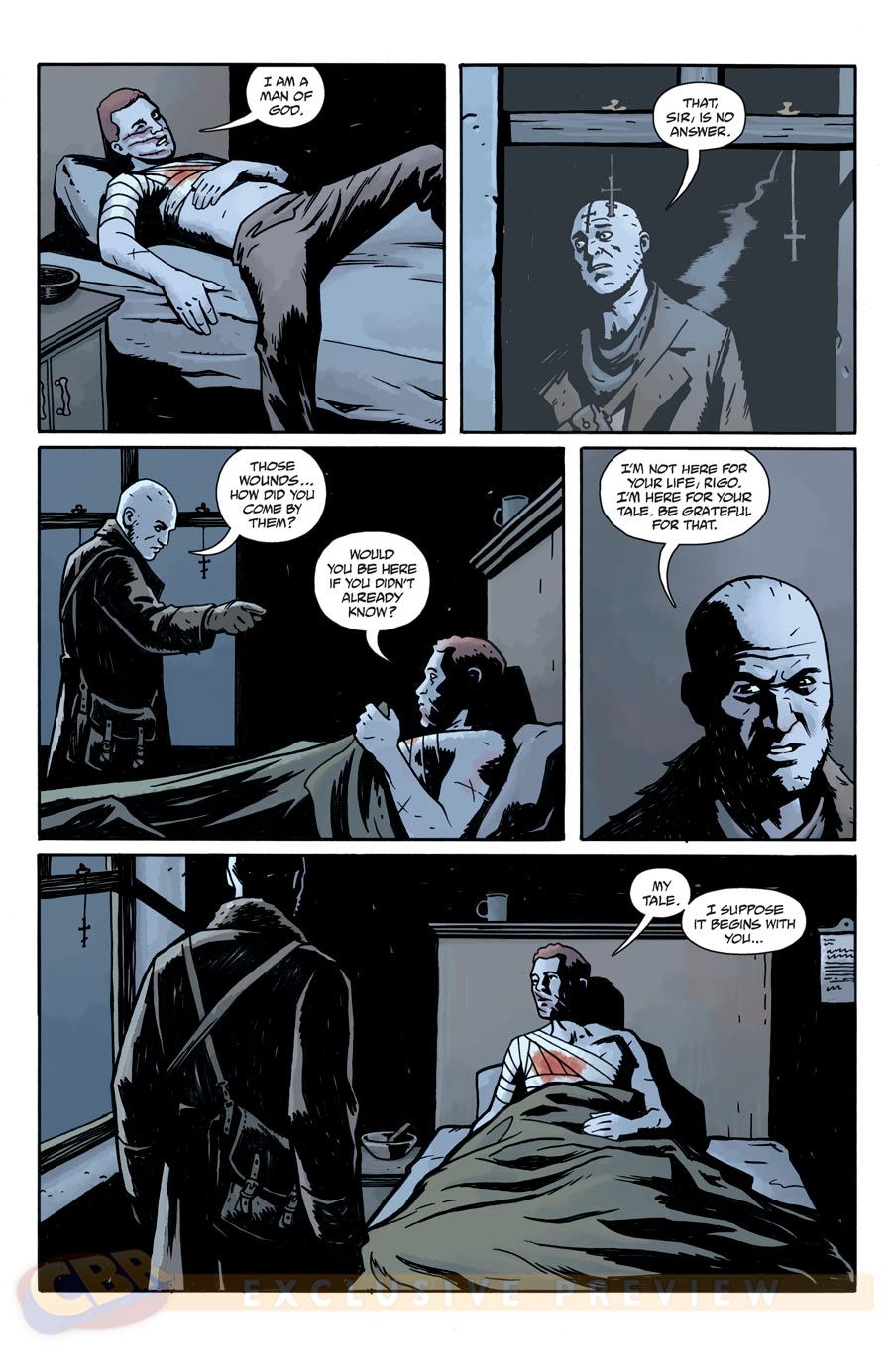

In looking at our sneak peek preview of the first issue, one has to appreciate your portrayal of the Inquisition agents. In particular, this first issue introduces readers to Rigo. First off, how did you and Mignola arrive at introducing him while being interrogated by Lord Baltimore?

Whenever we want to focus on a supporting character, I make sure to come up with a framing sequence using Baltimore to put the story into perspective. How does it work within the context of Baltimore's overall story? In this case, we knew wanted to begin with Rigo remembering all that's happened to him, which would help us include the backstory of the Inquisition itself in a way that would have felt forced if we had just started with Rigo and the other Inquisitors hunting for Judge Duvic. Beginning with the novel, and spreading throughout the history of the comics series, we've explored a lot of story-within-a-story structural stuff.

I also have a love for certain movies and books that begin with a "survivor" sitting around and telling people the tale of what he survived. "The Call of Cthulhu" is a great example. It made sense for Rigo to be telling his story to Baltimore instead of to one of the doctors or nurses caring for him. That also gave us the opportunity to portray Baltimore in a different sort of light. The monsters view him with a certain dread, but so does the Inquisition. He's halfway to being the devil himself as far as they're concerned.

What do you most enjoy about having these new characters, Baltimore's traveling companions, to write?

It's a very different kind of story now -- one that we're just gearing up to tell. That's another reason this is a perfect time to jump in. We're just beginning to explore who these people are who have been recruited by Baltimore to join his fight. From a writer's point of view, the companions allow me to humanize Baltimore to a certain degree, but also to shine a bright light on the ways in which he is becoming inhuman. We can't help but compare and contrast their humanity to his. From a plot perspective, once Baltimore realized that his battle was much larger than he'd originally thought -- that it was about more than just his personal vengeance -- it only made sense for him to pull in some of the people he trusted, all of whom have suffered their own losses to the darkness. The question is whether or not he's brought them in for his sake or for theirs. The larger question is, given a choice of advancing his crusade or saving the lives of his companions, what would he choose? Are they his friends, or simply tools he's acquired?

This particular story is a two-parter. Can you talk about the keys to successful pacing in a story such as this one?

There was never any question of length on this one. Despite the framing sequence with Baltimore and the bits of Inquisition history, it's a down and dirty story. A bunch of warrior priests track an insane werewolf to an abandoned castle overlooking the ocean and things get ugly and bloody very fast. That's not the kind of story that I'd ever stretch out. It only works if it's quick and nasty.

Looking back at your history of Baltimore stories, what are you most pleased in terms of world building in this corner of the fictional universe?

Ben, Peter and colorist Dave Stewart have brought to life everything I could have hoped for. I think readers have an excellent sense of how broken and desolate Europe is in the aftermath of the war and the plague. Trust is gone. Most towns have suffered catastrophic loss of life and people are wary of strangers -- and of those they've known all of their lives. The night is dangerous. In some places there is great sorrow and in others a real sense that daily life is tentative. Yes, we've carefully woven -- sometimes very quietly, in the background -- this huge mythology of the Red King, what he is, who his worshipers are, and where that's all going. But to me, the mythology of what Europe is like in Baltimore's time is just as fully fleshed and interesting, if not more so.

How critical is editor Scott Allie to the success of the Baltimore line?

Scott is Jiminy Cricket. He's my conscience. He looks over every script and always catches the things Mike and I have missed. I've known him more than twenty years, and I think he's developed an incredibly sharp editorial eye. He never tells us where to go, but his feedback is crucial to helping us get there. I was on the phone with him last week about another project, and his insight during that conversation has made it a thousand times easier for me to do my job going forward.

Many writers would love to get a chance to collaborate with Mike Mignola. Not asking for you to brag about yourself per se, but what is it about the collaborative dynamics between you two such a consistent, long-term team?

Mike and I are very different people, and we approach storytelling very differently. But I think, at the core of it, we usually care about the same things in a story. We have a shared frame of reference that is invaluable. For whatever reason, he seems to trust me. Beyond that, I have no idea.

Dave Stewart is a colorist much in demand, how fortunate is the Baltimore creative team to have him part of the crew?

Anyone who reads comics knows that Dave Stewart is the gold standard in coloring. He makes everything look two or three times better than it was before he got to work. Ben and Peter are fantastically talented guys, and so is Dave. The mood and atmosphere of the series, the coloring choices he makes -- Comics fans often overlook the artistry of coloring, but Dave is just as much an artist as any penciler or inker. He's the best there is.

As a veteran writer of horror, I am curious when writing comics are there ever scenes that you write which even take you by surprise (by its ferocity or what have you) when you the artist's interpretation of your words?

Rarely, but "The Wolf and the Apostle" is full of those scenes. It's one thing to write about a headless corpse kneeling in a hallway, it's another to see it drawn by Stenbeck and colored by Stewart.