In this column, Mark Ginocchio (from Chasing Amazing) takes a look at the gimmick covers from the 1990s and gives his take on whether the comic in question was just a gimmick or whether the comic within the gimmick cover was good. Hence "Gimmick or Good?" Here is an archive of all the comics featured so far. We continue with Spawn #1...

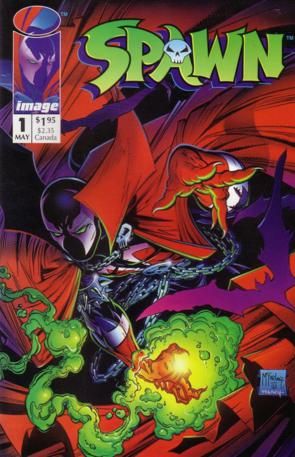

Spawn #1 (published May 1992) – story and art by Todd McFarlane

While Rob Liefeld’s Youngblood was the first title launched by Image Comics in 1992, Todd McFarlane’s Spawn was the publisher’s first true phenomenon, selling more than 1.7 million copies and spurring a major motion picture, an animated series and one of the most successful toy lines of all-time. And unlike nearly every other Image title that debuted in the early 1990s, Spawn has withstood the test of a time and is the company’s only original title, besides Savage Dragon, that is still being published today without any interruptions.

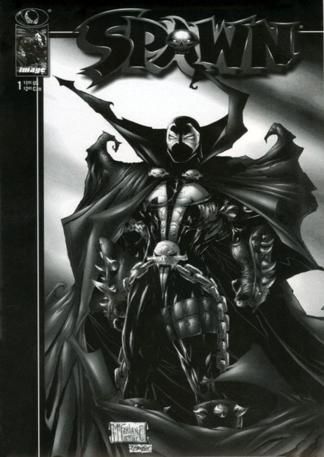

While this comic’s immense popularity was a key part of the comic book industry’s speculator boom – collector’s grabbed as many Spawn #1’s they could find in hopes that the issue would accrue in value – you might be asking yourself what’s the actual “cover gimmick” that qualifies this comic for a Gimmick or Good feature? There’s no foil, holograms, trading cards or polybags here. Well, I’ve found a loophole that allows me to write about Spawn #1. Fast forward five years after the comic was released. When sales for Spawn start sagging in 1997, Image issued a black and white reprint variant of Spawn #1 as a retailer incentive for their order of Spawn #65. Local comic book shops would get one Spawn #1 variant for every 50 copies of Spawn #65 they ordered. A CGC copy of this variant can sell upwards of $500 these days. Given the fact that retailer incentive variants are still a part of the industry today, I’m going to rule that this comic is absolutely in the sprit of Gimmick or Good?

So now that I’ve overly justified my choice, what about what’s inside the comic?

I was not particularly kind to McFarlane’s writing when I talked about Spider-Man #1 in this column a few months ago. I thought that comic’s script was overly stunted and clichéd and ultimately uninteresting (though the art was great). With that said, I actually think McFarlane shows vast improvement with Spawn #1. It’s still not a great story, but it smacks of infinitely more effort than “Torment,” which to me read like an artist who had been forced to write but had no interest in doing so. Spawn #1 still has McFarlane’s trademark flashy splash pages that offer little actual substance to the progression of the comic’s narrative, but in-between those moments, there’s a legitimate story unfolding here that’s drawing me in.

Using my power of 20-20 hindsight, McFarlane comes across as being more empowered as a writer in Spawn #1, and I would wager a lot of that has to do with the fact that he’s creating a script about a wholly original creation of his. I don’t think anyone can doubt McFarlane’s creativity as an artist – whether you actually like his artwork or not. But whatever inspiration and energy that was seemingly lacking during his Spider-Man run seems to be present in Spawn.

For one, McFarlane manages to create a legitimate air of mystery around his titular character. He reveals information about his character in bite-sized morsels and then ends the comic of enough of a cliffhanger that I want to keep reading. We learn from the onset that Spawn if former Lt. Col. Al Simmons, a highly-skilled CIA assasin who died, made some kind of deal with someone, and is now walking the earth again as the powerful Spawn. He is having visions of a woman for reasons he doesn’t initially understand (it turns out its his wife) and when he removes his costume near the comic’s end, Spawn discovers his some kind of hideous monster.

The comic is paced well enough where my interest mostly remains piqued from start to finish. There are a few instances where my attention wavers a bit: McFarlane uses three television news reporters to push the narrative forward about Simmons’ CIA background, and later in the comic, Spawn’s path of mob destruction. These pages are so static and text-heavy they are a total style-clash to McFarlane’s more action-driven work. Fortunately, there’s only two pages where McFarlane deploys this technique, but they feel out of place and overly recappy all the same.

Overall, there’s nothing groundbreaking about what McFarlane has crafted here – Faustian deals with the devil have been a staple of storytelling for centuries – but Marlow and Goethe never had the advantage of having an superstar artist as an illustrator. More importantly, McFarlane seems to be having so much more fun creating Spawn than he did on Spider-Man, which in turn makes the reading experience infinitely more enjoyable.

Verdict: Good