Yesterday, CBR and a panel of creators and editors explored the changing landscape of fandom, which, in recent years especially, has become more diverse than ever. From an increasing female audience to the growing representation of the world's true multi-cultural diversity, the comics industry and fandom alike are experiencing numerous changes in a compressed span of time, which makes calm, reasoned discussion more important than ever.

RELATED: Gillen, Wilson, Lark & Huehner On Creative Process, Importance of Reflecting Modern Fandom - Part 1

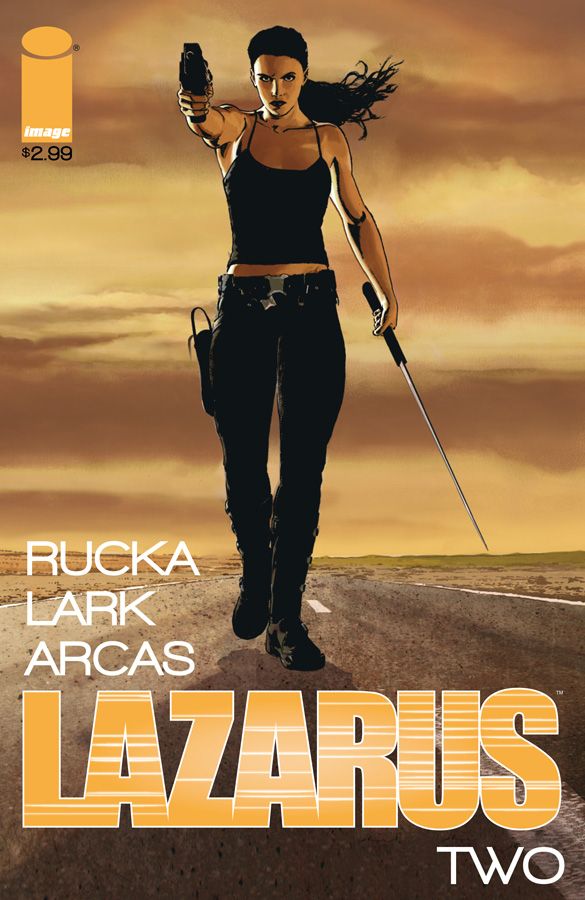

Today, in the second of a two-part discussion, Kieron Gillen (writer, "Wicked + the Divine," "Young Avengers"), Mariah Huehner (Editor, IDW Publishing; writer, "Angel"), G. Willow Wilson (writer, "Ms. Marvel") and Michael Lark (artist, "Lazarus") rejoin CBR News to discuss the best way to balance the needs and desires of a readership with the creative team's vision, and the difference between depicting sexy versus sexualized female characters. We also dig into the true risk involved in attempting honest depictions of various races and creeds in your work and the responsibility those in editorial and creative positions, as well as fandom as a whole, has in setting the tone of the modern comics industry.

CBR News: What does the decision making process look like? When there's pushback, what is the right way to be flexible and balance the needs of the business with the needs of the reader?

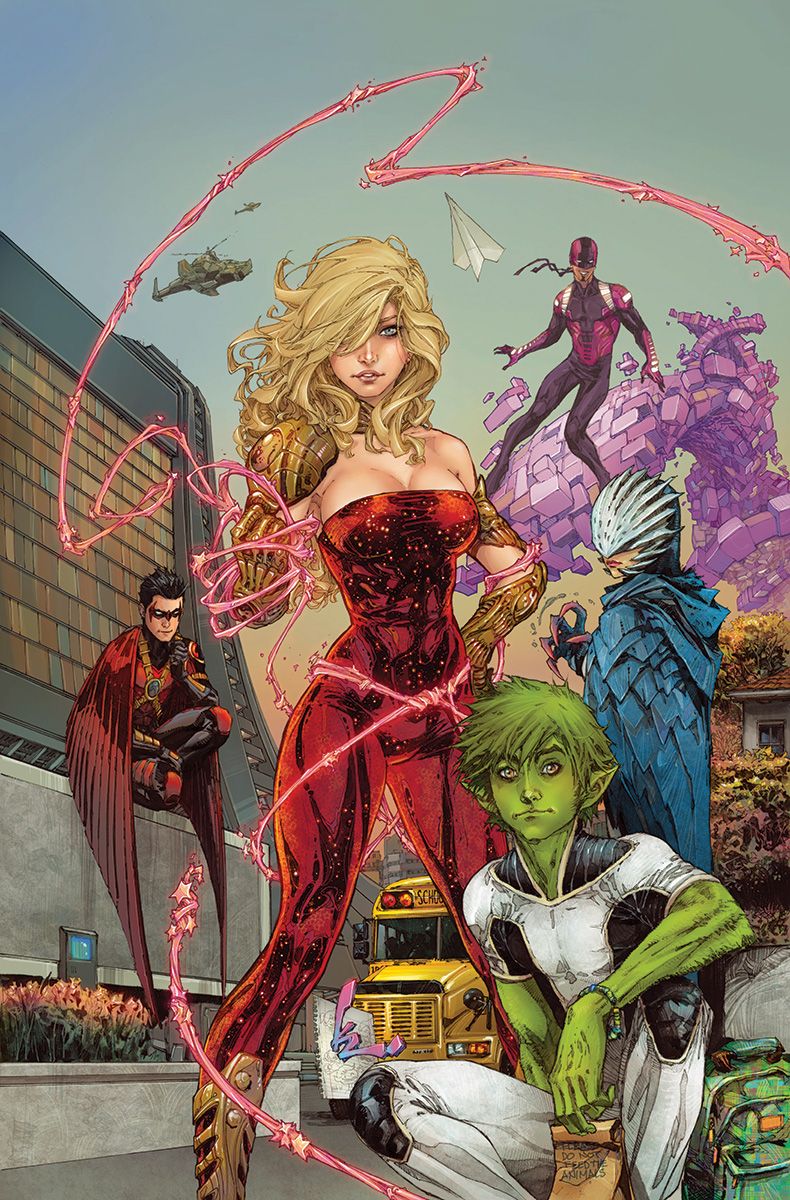

G. Willow Wilson: When the stuff that is problematic gets the green light, more often than not it's a matter of people not paying attention somewhere in the pipeline. Janelle Asselin's article about "Teen Titans" -- with the DDD porn star boobs they put on a 17 year-old girl -- I can say with as close to absolute certainty as one can get without having been in the room that nobody sat around like, "How can we sex this character up?" It's just that the status quo sometimes is very hard to reach escape velocity from. I'm sure that when the guys sitting in the room, and I'm sure it was mainly guys, looked at the art they went, "Oh, this is how superheroes look."

It's that reflex. It's still there. The internal dialogue hasn't happened where they feel like they should have another set of eyes on something. It's difficult sometimes to hold up that mirror and look at your own preconceptions be like, "Wait a second, maybe I should take another look at this." I'm sure people don't sit down and set out to make inappropriate graphic depictions of underage girls, I think the dialogue is what's important. I hope that now these things have come out, covers like that get a second look.

When there is a discussion being had about how a character should look, it's typically the writer, the artist and the editor [are] in a room going through a bunch of iterations. It really depends on who is in the room and what their priorities are. When you get people in the room who are not thinking about these kinds of things -- is this an accurate or fair depiction of this character, what would an actual person wear to go fight bad guys -- those questions aren't asked because they aren't a priority. That's how you get distasteful things and controversy. But if there are people in the room who make those questions a priority, then there's a check and balance.

Honestly, it's more about personality than it is about process. It's important to have diversity in voices not only on the creator side, but also on the editorial side.

What role have fans played in getting this conversation going?

Wilson: The fan's role in all of this cannot be overstated. All of this change has been fan-driven more than anything else. I can remember when I started out back in the mid-2000s; a lot of these conversations were not being had. There were very sympathetic editors, and I remember working closely with several of them, who were passionate about getting more female heroes on the page dressed in things you could actually get into a fight in. There just wasn't a ton of fan support for that kind of stuff. Now that the fans are engaged, that's what I think is driving the change. The blogging, the reporting, people getting up at panels, that's what's really created this change.

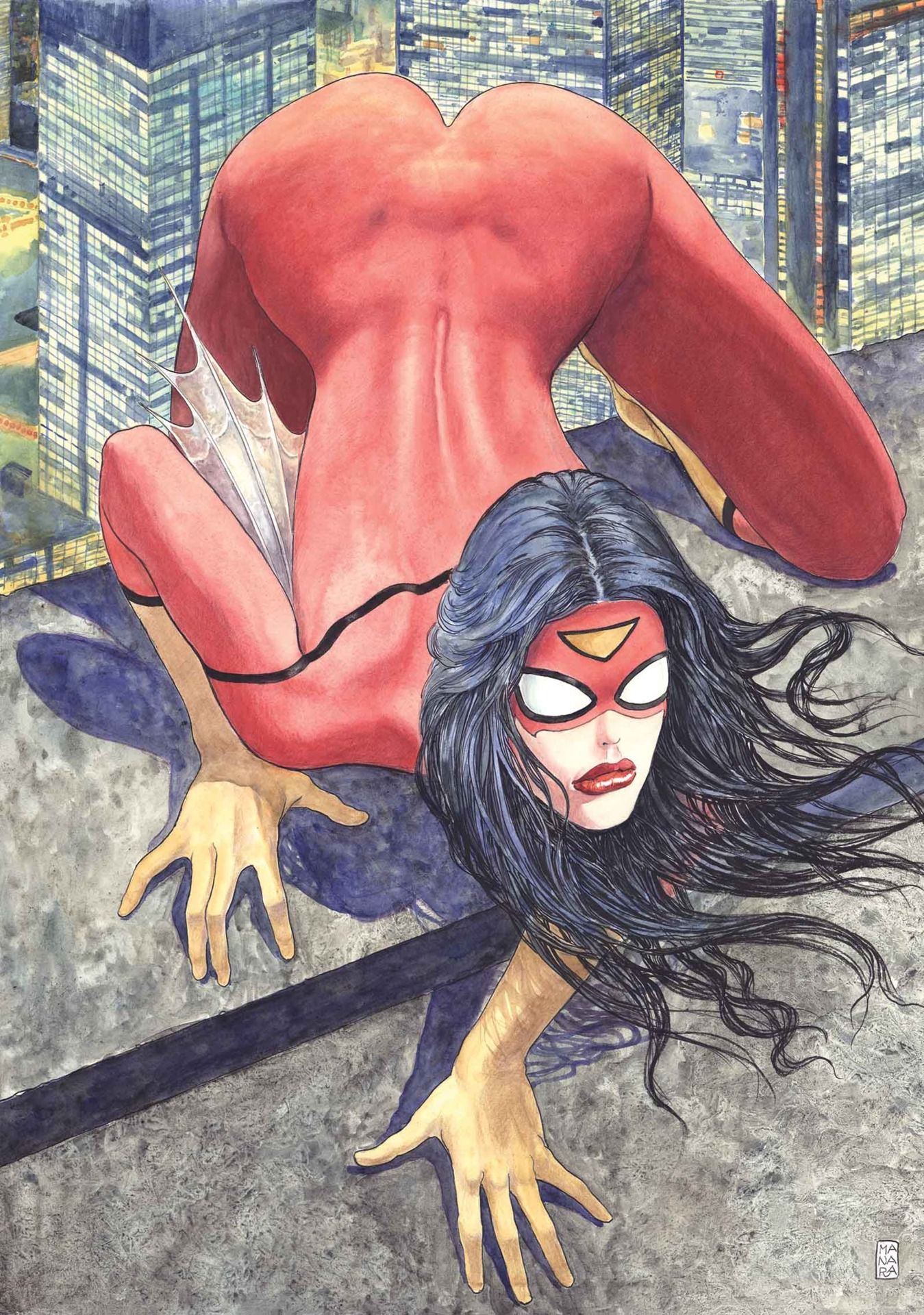

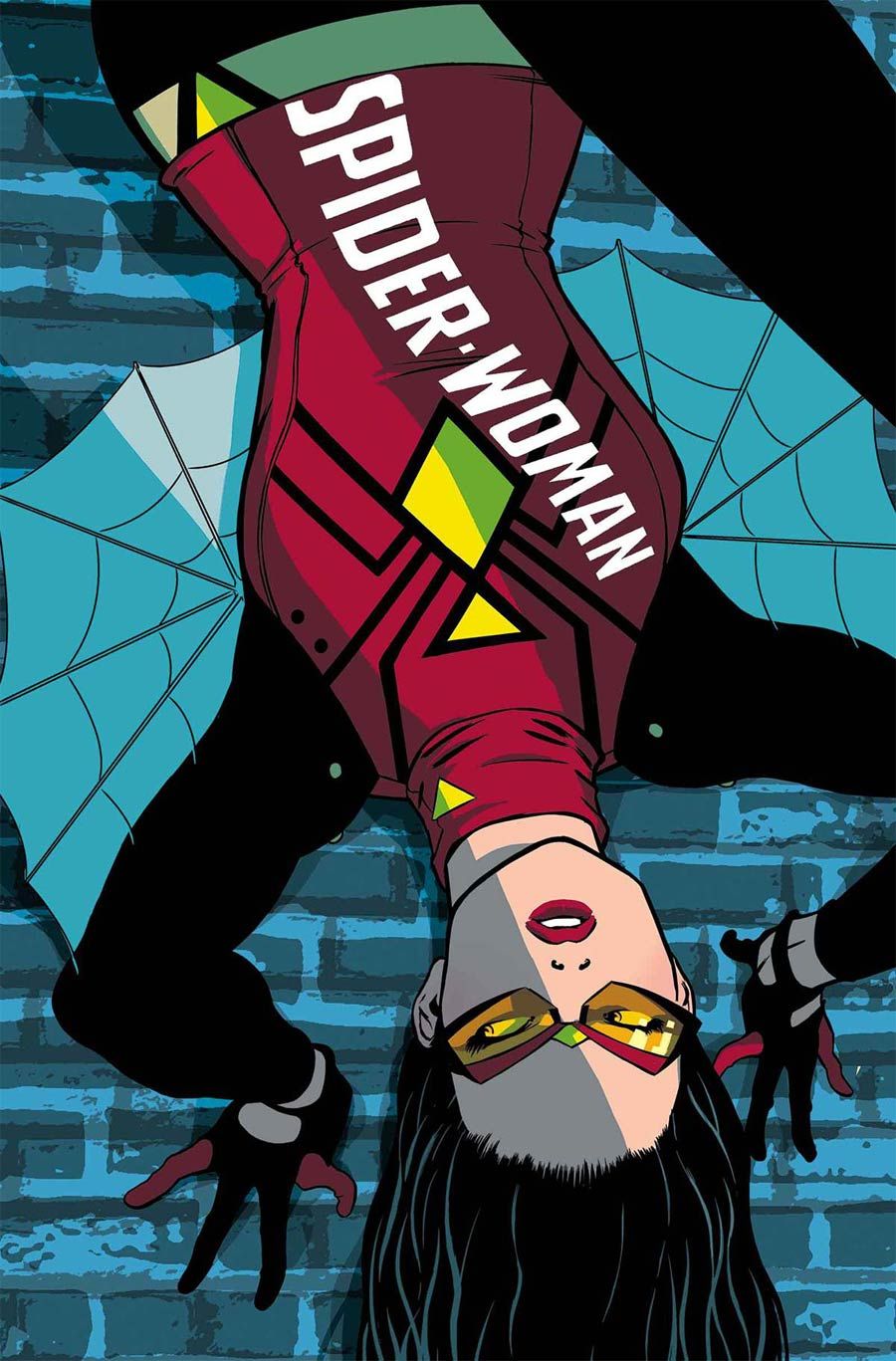

When you see things like the "Teen Titans" cover or the "Spider-Woman" variant cover, where women are shown sexualized in ways that don't suit their character, what are your thoughts?

Mariah Huehner: My first thought is usually sympathy for the editor because we all make mistakes and, generally, I don't think anyone is maliciously setting out to upset people. But they're still mistakes and ultimately editors are responsible and have to own the decision. After the sympathy, though, I'm often disappointed and can be a bit hard on other editors because I think we can and should be better at spotting this kind of thing. And maybe more importantly, better at taking responsibility when we mess up.

Sometimes you just make a bad call. Maybe you didn't see a problem; we aren't all bothered by the same imagery. There's very little that actually offends me, for instance, which means I have to be that much more vigilant because it would be really easy for me to assume that, because I'm not bothered, no one else should be either. And that's really not how it works. Plus, because a specific kind of sexualized image of female characters is so common in comics, you can probably get a kind of blindness to it. Which is, in and of itself, a problem.

I think at this point we should be able to see the obvious problems with something like the "Teen Titans" or "Spider-Woman" covers -- the inconsistent messaging, the disconnect with intended audience and tone. It's not like we haven't been discussing this kind of imagery for a while now, so while I think people can miss it, it's partly because they aren't looking. As an excuse, that starts to ring really hollow and we have to do better than that.

Beyond that, I get annoyed that the default treatment of so many female characters is "sexy" before anything else. And that the idea of "sexy" has become so bland, one note, and boring. What happened to pinups with humor and personality? What happened to cheekiness of expression rather than just... cheekiness? Blank expressions in revealing clothing isn't really a character being sexy because there is no character. It's the Sexy Lamp problem again. It's not telling you anything about who they are or the story or anything. And covers have a responsibility to be, in my opinion, relevant. Variant or otherwise.

At the end of the day I think what those covers often signify is "mainstream" comics' identity crisis. They've been getting away with almost-porn imagery for so long they've forgotten that it often makes no story or character sense and, therefore, shouldn't be on any official image representing a book that isn't porn or pseudo-porn. It's that simple.

To be clear, I don't think people in comics wake up in the morning and say, "Gee, I wonder who I can offend today!" I think a lot of these choices are made based on tired tropes, outdated points of a view and a certain sort of socialization that makes it okay. Do you think conversations between the creators, editor and/or publisher are happening?

Kieron Gillen: This one just seems to be too large to give any kind of answer. This is as different as every creator and every editor, and all the relationships herein. I'm hyper-aware as a Brit writing for a primarily American audience that my socialization is simply not the same as U.S. socialization.

I try to be optimistic. It's like what I say about the whole [video] games as art argument. Games will be accepted as art when all the old people die off. We just have to wait. What you're talking about here is a process, and while the improvement is frequently slow and that slowness is painful, it goes through periods of flux. Today's progressives will be viewed as all kinds of problematic in 20 years by the progressives of 20 years in the future. This is life and art.

What do you think conversations between the creators, editor and publisher look like regarding these choices? Are they happening?

Gillen: I think at this point it's clear who's having those conversations and who isn't. You can see it in the storylines, you can see it in the art, you can see it in the diversity -- or lack thereof -- in the characters. I think they're happening, but I think it's more on an individual editor/creator scale than company-wide edicts in most cases. Sometimes that's because a company is too big and you wouldn't want books by committee. I've seen that; the result is often what you'd expect when too many people are poking around in a story. I think it's also because a lot of responsibility does fall on individuals rather than groups. I think we are seeing more active diversity which is partly why, when there's a slip, it's that much more disappointing. Like, how can you get it right here but then miss it so spectacularly here? It's a process.

So I think the conversations are happening. I know they are. And you can see it in the books that are embracing all kinds of points of view and genres and creators. It's just happening more slowly in some places than others.

Do you think publishers see a risk in embracing more diversity or challenging existing stereotypes? If so, what do you think the risk is?

Gillen: The risk is that you end up doing it badly. That's what scares most people from trying it. Losing the audience who just can't process any diversity without seeing it as "diversity for the sake of diversity" -- which translates as, "I cannot see these people as human beings like I am." That's a real financial risk.

Huehner: I think there's definitely been fear about losing the core audience. The Big Two have expressed that very concern, publicly. That if they embrace other audiences, like women, that their core audience will throw a fit. Honestly, I find it to be an excuse. I'm not saying some of that audience won't throw a tantrum and possibly stop reading, but the potential audiences are so much bigger that it seems silly to me to not reach out because of a few narrow minded "fans." If they were actually fans they'd want comics to grow, not shrink. And I really don't think comics can afford to keep pandering to only one group or they're risking complete obscurity and irrelevance.

It should be noted: I don't think indie publishers have the same fear. I think this is more of a Big Two concern. Indie folks have been reaching out to wider audiences for a long time or they wouldn't survive. They already know you can't rely on one demographic.

What is the responsibility of people in power -- creators, publishers, editors, journalists -- to set the tone they want to see in the community? What do you think the fan responsibility is?

Gillen: Perhaps surprisingly given my answers above, I don't think a creator has any responsibility. I think a creator deciding what they want to do with their art is entirely their own decision. I have a responsibility because Ichooseto have a responsibility. There's no "should" in art. If you want to choose to be immoral and monstrous, go knock yourself out. Just don't act all coy and innocent when you get the inevitable response. Regarding fans, I would encourage them to be a little more relaxed about books that aren't for them. Not everything is about you, or me, or anyone. That'd be nice.

Huehner: Well, we're all in it together. We're all responsible for the culture around comics, for one thing. And it's a really tight knit, small group, when you think about it. So how we engage with one another, what stories we tell, whose voices we value; it all adds up to shaping the storytelling medium as a whole.

Which is something I think a lot of people forget. Comics are a medium, not a genre. It isn't supes or autobio or sci-fi. It's everything. You can tell any kind of story in comics, from every POV, and that's an incredible thing. We have the ability to tell meaningful, fun, silly, serious, ridiculous stories of all sorts. The more perspectives we embrace and celebrate, the richer the whole experience is.

So I think that's our collective responsibility: celebrating stories of all kinds, creators of all kinds, and audiences of all kinds. Creating work that isn't stagnant but challenging and engaging. Everyone will benefit from books and a community that are welcoming, not limiting.

Wilson: Change is inevitable. Nobody wants to alienate the original fan base, but we can make more room at the table for more people. At the same time, what drives these decisions is what sells.

I can remember a perfect example of this. I was on a Marvel panel at a convention recently and a fan got up and asked when we would see more unique events, and not just a series where the world is going to end again. People laughed, and then one of the executives on the panel said, "Well, we'll make those books when you guys buy them. You guys say that, but what you buy is the event stuff."

There's still a bit of a collector mentality -- I'm not saying that's good or bad, it just is. People want to buy the stuff that sounds important. So that's still there. It really is a matter of following the market and this is true of mainstream publishing is well: people often say they want one thing, but they'll buy another. As long as people are buying 150,000 copies a month of the event books, that's what's going to keep coming out. What's necessary to create any sort of seismic shift would be people buying a different kind of title with those kind of numbers, like 140,000 copies of "She-Hulk" or an indie book. All of a sudden, the whole "Big Two" thing is upset and we have other players on the field. That has to happen in order for there to be some enormous generational shift in another direction.

But there is real change. We are seeing actual change in the numbers as well. I know personally with "Ms. Marvel," we've all sort of been blown away by the fan response and the way it's been selling. I'm just stunned, and I feel like I'm not doing anything differently than I usually do. It's a matter of the climate -- right place, right time.

I really have to hand it to some of the popular creators who've gone out on a limb to draw lines and say they won't tolerate bullying or sexual harassment in the community. Gail Simone comes to mind as someone who has called people out in the industry at no small risk to her own standing. These are people who could give her jobs, who are her colleagues, and she's gone to the mat on many occasions to defend people on the fringes. Steve Niles comes to mind, the original vampire man -- when people like that are willing to take on these issues, the issues become a much bigger deal.

There are tastemakers whose role it is to lead the conversation because they have such a big platform and a dedicated following. It certainly makes a difference when they're willing to come out and draw the line about what they will and won't tolerate.

Michael Lark: The people in power are just going to be a reflection of the rest of fandom and the rest of society. I think that it's more a case of people like us at the grassroots saying something about it. At the convention when I saw that banner, I spoke to some friends involved with the convention and I got a lot of pushback about it. It was shocking, because these are good people, people that have daughters. I know they wouldn't want them to see that, but I was told that I was engaging in censorship.

I think it's up to us to risk that blowback we get to stand up and say something, to say it's not cool. It's not okay for people to say the crap they say. If we expect it to come from the top, we're going to be waiting for a while. The people at the "top" are much more interested in selling their product, and if sexually exploitive comics sell, then they're going to be okay with that. It's not that they're necessarily bad people or anything; it's just the way it is. It's the reality of the marketplace.

It's one of the reasons you see a difference at some of the smaller press publishers. I don't think there is anybody coming down from on high saying that books at Image or Oni or wherever should be a certain way; I think the creators have more of a say. The creators are doing their own thing. I think if you've got people that are publishing at a place like Image or Oni, you're generally dealing with people who are dissatisfied with the status quo. It's really easy to work for Marvel or DC once you're in the door, but it's a lot harder to create your own thing, to find your own voice. It's a risk we take. But if you're expecting the people at the top of The Big Two to be the voice of reason on this stuff, it's probably not going to happen. I realize I sound very cynical, but that's been my experience.

Again, that's an uphill battle. You're asking people to take a risk and as corporate entities, they are, by their nature, averse to taking risk. That's why it's a really exciting time to be in comics, because all these small press publishers are making a much bigger splash than they used to. Marvel and DC aren't the only game in town anymore.