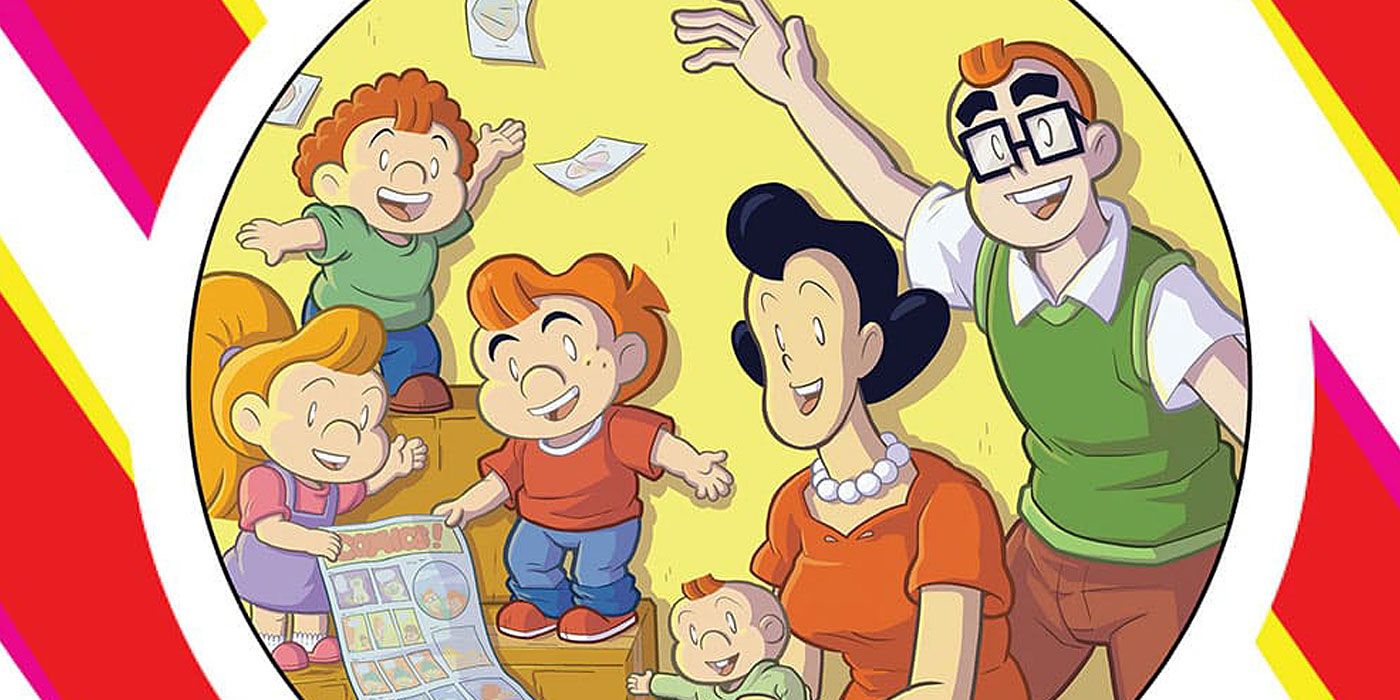

Best known for “Ayn Rand’s Adventures in Wonderland,” this year sees the release of Benjamin Frisch's first full length graphic novel, “The Fun Family.” The book has been called a satire of “The Family Circus,” but while that may have been part of the initial idea, the final project is much more than that. Frisch developed a new drawing style for the Top Shelf-published book, and he clearly takes the characters and their world seriously, even if they’re cartoonish and satirical.

In addition to his comics work, Frisch is also an audio producer, working on "Out on the Wire," the podcast from Jessica Abel about her recent book and creativity. He's the current producer of the weekly podcast "Slate’s Culture Gabfest," and freelances for NPR, KCRW’s Unfictional, and the recent story “Upper Left,” which appeared on the podcast Love+Radio.

Frisch spoke with CBR about telling meta stories, how perspective drawing comes naturally to him, and the similarities between the two visual mediums he works in.

CBR: Where did the idea of “The Fun Family” originate?

Benjamin Frisch: I’d always been fascinated by “The Family Circus.” It’s the kind of thing that’s always there -- it was never not there. It never seemed really appropriate for any time or place. I think that newspaper comic strips generally feel more and more like that, but “The Family Circus” in particular seemed to serve a purpose that I didn’t understand. It was always this kitsch object that was always a part of our lives. Somebody had announced that they had acquired the rights to do a live action “Family Circus” movie -- this was in 2010 or 2011. On a whim, I wrote down, what would my version of a live action “Family Circus” movie be? I wrote it down... and then I lost it, but over the next couple weeks I kept coming back to the ideas that I had written down.

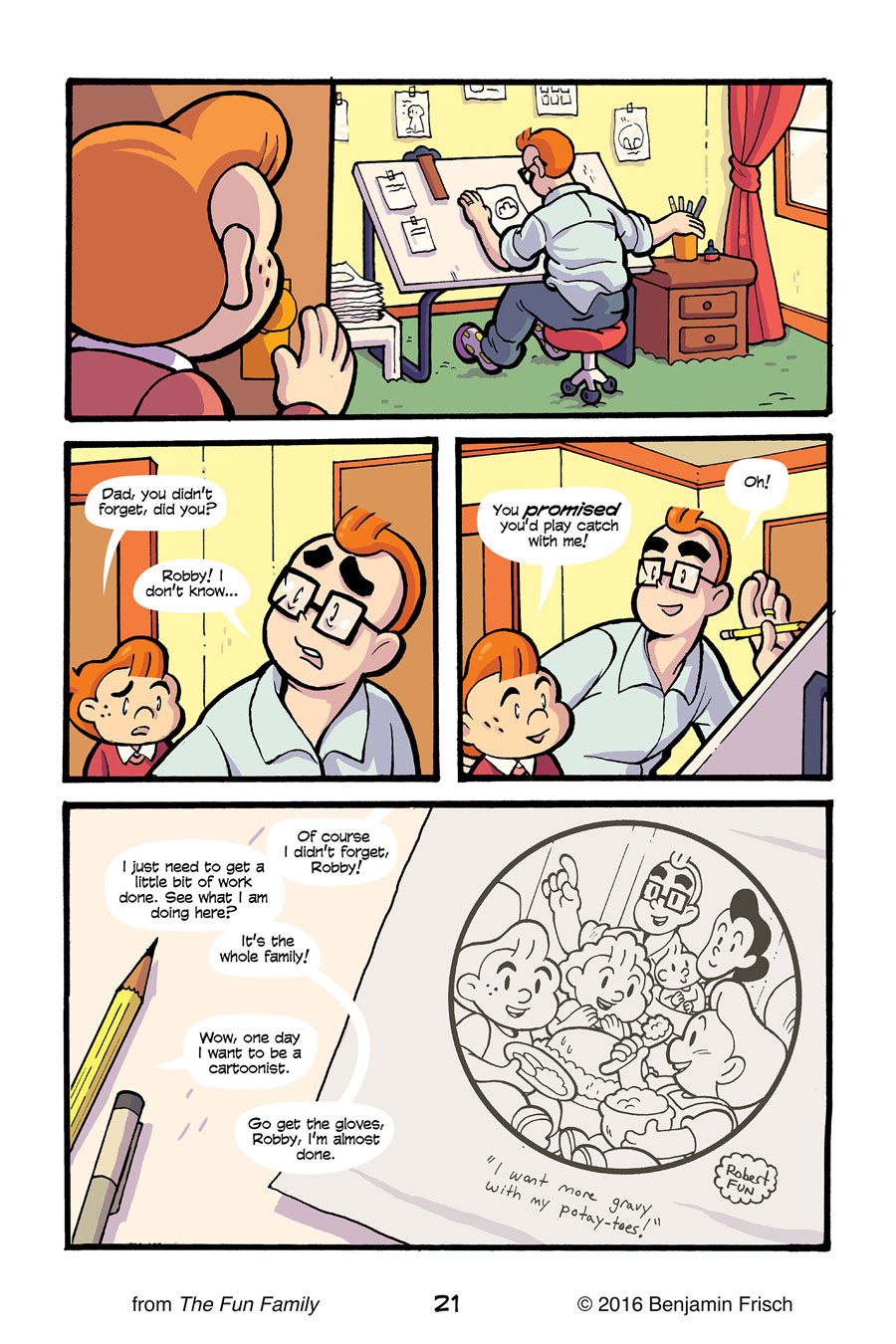

This original idea was probably about sixty percent of what “The Fun Family” is. This meta family drama about a father who draws a comic strip and all the members of the family are trying to figure out what their life is in the aftermath of their family breaking down and having to contend with the idea of their family in the comic strip. I was also very inspired by the book “The Broom of the System” by David Foster Wallace. They never made that “Family Circus” movie. That movie is never going to get made. It doesn’t make any sense. There’s no conflict, which is fine for a one-panel strip, but for a film, that creates some problems.

There’s always been a certain unreality to the strip which you reflect in the book. It’s not, for example, tied to a specific time or place. It’s just out of time.

There are all these premises that go unexplored. The fact that the father draws a comic strip -- which is by far the most interesting to me and the one the book is based around. The “Not Me”s and the little ghosts are so weird. I think I originally intended to have more of that in the book, but I backed off because I wanted to book to stand on its own. The book is coming out in French this month and I’m super excited, but French people have no idea what “The Family Circus” is. To them, it might as well not exist, but they still seem to understand the story. That was important for me.

At the center of the book, it’s about a father who has taken this idea of the family and turned it into this saccharine image.

I see Robbie as the protagonist of the story, but yeah, that’s certainly what the base of the book is about. How do we tell stories about our own lives that aren’t necessarily fictional because stories are convention. We create beginnings and endings and conflicts and they all get tied up in this clockwork way in a classical story, but in real life that’s not actually how anything works. And yet the human experience is completely narrated through stories. I think there’s this huge contradiction in what it means to understand the world and also to live psychologically as a human. That’s something that I’ve always been interested in exploring. All my work is really meta. I’m drawn to work like Charlie Kaufman’s films, “Pale Fire” by Nabokov. I know a lot of meta stuff turns off a lot of people, but I’ve never understood why.

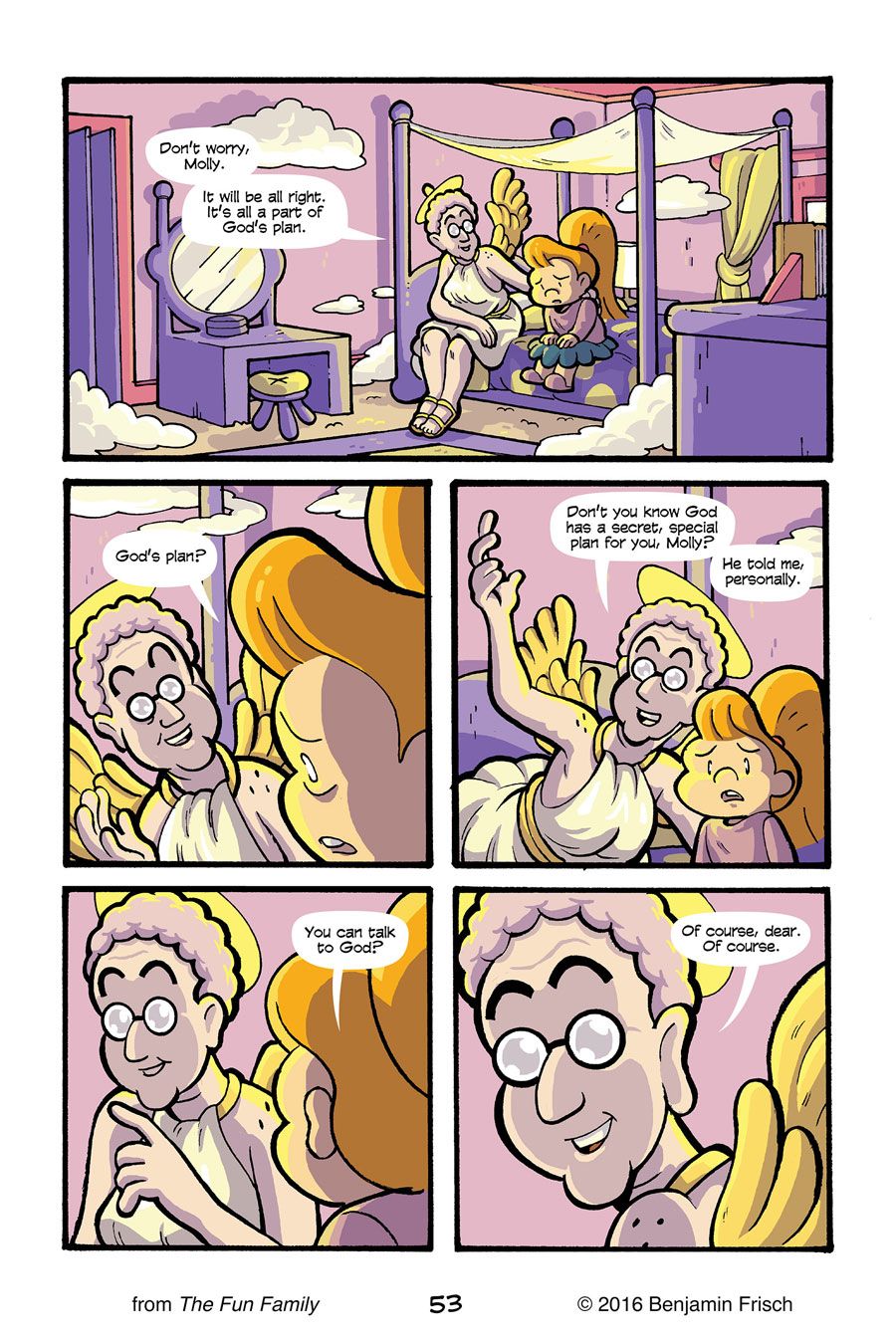

It’s sort of a book about coping. All the characters basically find a way to cope by the end.

Sometimes in unhealthy ways.

I don’t know. I think that often times people proscribe intentions to me from reading the book that maybe I’m a little bit more agnostic on. I have a lot of sympathy for all of the characters -- with a couple exceptions -- but I have at least some sympathy for all of the family members. Everybody’s got to get through the day. If you can do that in a way that doesn’t actively hurt other people, then whatever. It gets much more complicated when what you’re doing is actively harmful to the rest of your family, which is sort of what happens in the story. So... maybe not a good example. [Laughs]

Bill Griffith, who draws “Zippy,” has said that his strip and “The Family Circus” are the two surrealist comic strips in the newspaper. I always thought that’s an interesting way to read it.

It’s a little like David Lynch, where if you keep presenting an image of idealized family life, you just stop believing it. Lynch does this to great effect in the first act of “Mulholland Drive,” which was originally a TV movie, and it’s shot like a TV movie. But because everything is over lit and has this glow about it–this Sunday afternoon Lifetime Channel movie glow–it feels like something is wrong. For a lot of people like me when we read “The Family Circus,” because it’s so light and so sweet and cute, our natural cynical reaction is to go, there’s something really wrong here. On the show that I produce one our hosts was in California and was saying you’re in Santa Monica and it’s just so nice that something must be wrong. That’s definitely “The Family Circus” to me. That’s also a very personal reaction of somebody who grew up in a stable two parent family.

Lynda Barry has told a story that I find incredibly moving about how she grew up in very difficult circumstances. She would read “The Family Circus,” and for her it was this window into a different world. Life doesn’t have to be this way, life can be stable and sweet. Her personal story is much more powerful than me being snarky about “The Family Circus.” Or anyone being snarky about “The Family Circus.” It actually had a positive effect on a person and helped them cope with their circumstances. That’s why I’m really careful to say that I don’t hate “The Family Circus.” I think that it does serve a function and has served a function. At the same time, it is totally singular cultural object that is so weird, it’s so much fun to read into because it’s so totally opaque. There’s all these comic strips on the internet and tumblr that re-imagine “The Family Circus” where everybody’s doing drugs or whatever. I didn’t want to do that because I felt like it had been done. Some of them are funny and some I don’t think are that funny, but that wasn’t where I wanted to take the story. That idea is very played out. I thought it was much more interesting to play with the conventions of it and try to create something new out of it.

You went to school for art at Savannah College of Art and Design. When did you start working in radio?

I was involved in the college radio station pretty heavily and at one point started doing radio news and reporting. That’s how I learned the basics of how you record in the field, how you write for radio. I did that for a few years. I interned at NPR in DC. I like radio because unlike comics you’re still constructing a story but unlike in comics, you’re not responsible for all of the pieces. You’re responsible for letting the pieces happen, but ultimately you’re taking the words of others. People generally don’t realize how much editing there is in radio. That’s due to our own expertise because we make it sound like there’s no editing. Ultimately the two mediums have a lot in common, I think, because you’re still rearranging story elements to make something as powerful as possible. Whether that’s panels or pieces of audio, they’ve always felt pretty analogous to me. The only reason I’m any good at radio storytelling is because I’m educated in how to tell a story visually.

I interviewed Jessica about “Out on the Wire” when the book came out, and I got her story of making the podcast. When did you get involved?

Jessica had finished the book and she had given me a galley copy to read. I had read her "How to Make Radio" book that she had made with This American Life when I was first starting out in radio. It was pretty cool because she had written this thing that had influenced me quite a bit, and all the stuff about storytelling is still very relevant, but all the technological stuff is pretty out of date. Even when I read it when I was in college it was pretty out of date. Still I learned a lot from that book so it was really cool to have this new book which was much expanded and to be able to talk to Jessica about it. One day she told me, I did all these interviews for this book and they’re all recorded. I don’t know what I should do with them. Maybe I should make a blog post or maybe I should make a podcast.

She knew that I had some radio experience and so we said, let’s make a podcast. Originally it was going to be a very short small thing and then it turned into this really big project that was an adaptation of the book that also became its own thing with audience participation and workshop episodes. It was really exciting to do because it felt like we were doing something new and different and really worthwhile. I was looking at the stats on the podcast and we get like 400 downloads a week still and pretty steady. For something that’s finished, that’s pretty amazing. It’s really cool that it’s been really helpful to people.

Have you started working on or thinking about a new comics project?

I have two projects that I really like and am excited about. One of which I think that I would write and have someone else draw. The other I might draw myself. I adopted a style to draw “The Fun Family.” I don’t draw like that normally. But after drawing a 240 page book, it sticks a little bit. I drew a lot in France, and there are things I love about some of the work I did, but I just feel like I’m at a stylistic dead end and I’m trying to figure out what to do next. Maybe that means keeping some of those features and deconstructing them super super far. There’s a comic I’m obsessed with at the moment. You know the “FLCL” comics that are super deconstructed and people who have bad taste will look at them and say, this looks like it was drawn by a four year old but they’re actually super super sophisticated? That’s the kind of work I find inspiring at the moment.

“The Fun Family” is just so constructed. I drew a perspective grid on pretty much every panel. The panels look better and it’s actually faster for me if I draw perspective grids. The result of that is you have this very constructed style where everything feels like it’s in a realistic-ish setting even if it’s cartoony. I like that a lot about the style of the book. I think it fits the book really well, but not necessarily for other projects. I don’t think that artists need to have one style for their whole career. I think that’s a really bad idea actually. To an extent your style is the way that you draw, but I think a larger component for skilled artists–especially people who have a command of drawing as a form–is just choice and taste. It’s how you chose to draw. That’s why “The Fun Family” looks the way it does. It looks like something that was inspired by “The Family Circus” and children’s cartoons rather than anything else. There was definitely a period in which I had to learn how to draw that way. It’s a fairly simple style but the characters exist in the space in a certain way and you have to learn what that means in any specific style because they all exist in environments. I really like drawing backgrounds and figuring out how to fit the characters into them naturally and I didn’t realize that until I started doing the book.

Part of it is I just find it pleasurable to draw. They’re very systematic and you’re following a perspective grid and it’s fun and it makes sense to me. Some people have a really hard time with perspective, but perspective has always made sense to me. If I’m critiquing a piece and there’s something off about the perspective, I notice it immediately and see things that other people don’t see. On the other hand if there’s something wrong with a character’s anatomy, that’s the kind of thing I don’t notice.My brain is just wired to understand perspective naturally in a way that it doesn’t understand other things. I had a professor once who said that students naturally took either to figure drawing or to perspective drawing. I am definitely more inclined towards perspective drawing, even though it’s like not the majority of the work that I’ve ever done.

It’s a series of decisions. One thing leads to another in a way that seems very logical and systematic to me, whereas drawing characters is always what am I doing wrong here, this makes no sense, why does this hand look like garbage? [Laughs] I know a lot of people feel that way about perspective drawing, but not me. Honestly my life would be a lot easier if that were reversed. But I’ll take it. [Laughs]