Full disclosure: this isn't really about comics. But it brushes up against them, and also animated cartoons, in a couple of places.

I've mentioned this a time or two here before, but in addition to comics and pulp fiction, I'm also very fond of what used to be called "young adult" series adventure novels.

Today they've largely disappeared from the bookstores, though revamped versions of the Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew are hanging in there. (And there's an argument to be made that perhaps the Harry Potter or Twilight series of books are the newest incarnation of the genre.)

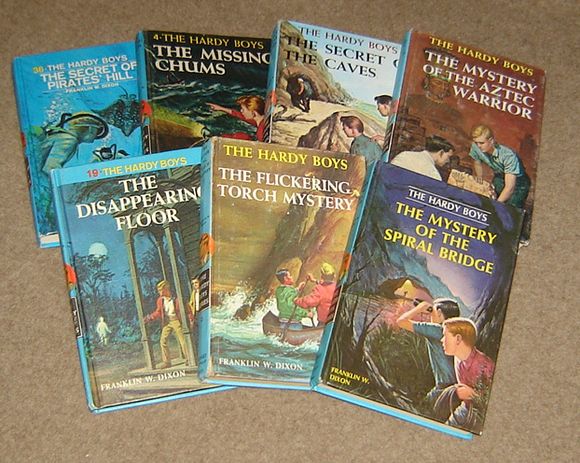

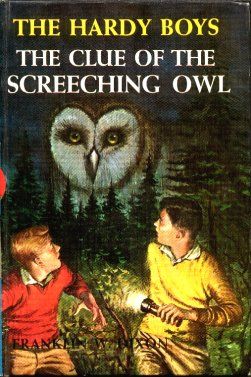

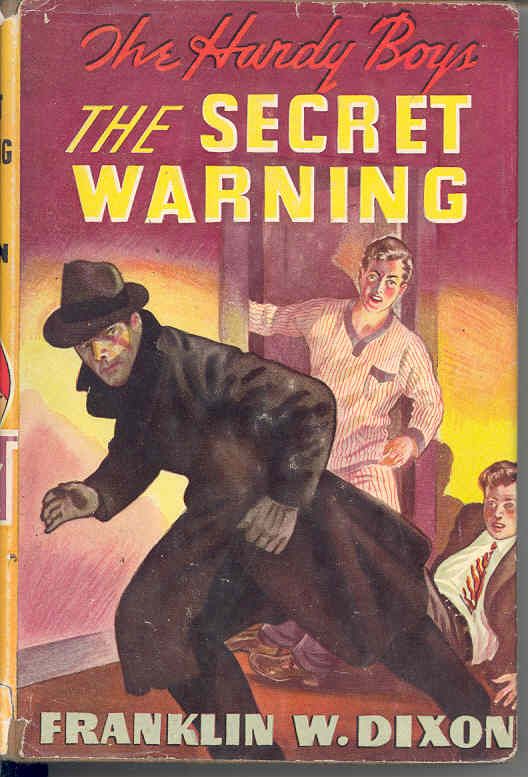

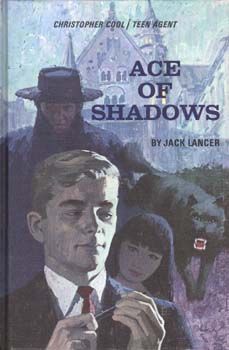

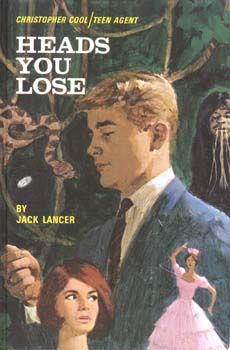

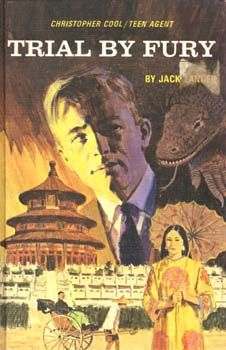

But the ones I'm talking about had a very specific look and format. They were hardcovers, seven inches tall by five-and-a-half inches wide, no dust jacket, roughly two hundred and forty pages or so... and always with a pulpy cover illustration that promised excitement with a touch of weirdness.

Most of these juvenile series books came from one source -- the Stratemeyer Syndicate. They packaged Nancy Drew, the Hardy Boys, Tom Swift, the Bobbsey Twins, the Dana Girls, and literally dozens of others -- well over a hundred different series, over 1200 books in all, were launched between the company's start in 1905 and its eventual buyout by Simon and Schuster in 1984.

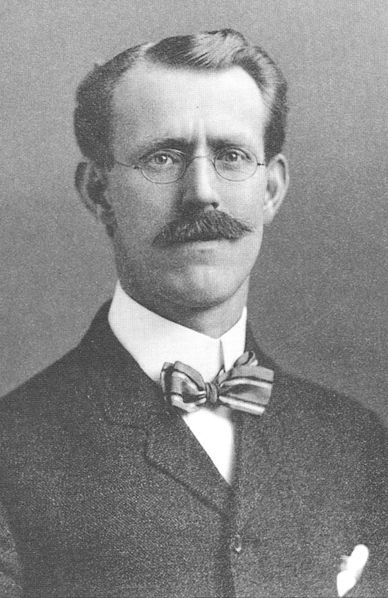

This juvenile-book publishing juggernaut was the brainchild of a man named Edward Stratemeyer, who started with The Rover Boys in 1899.

Edward Stratemeyer wrote the Rover Boys books himself, under the pseudonym "Arthur Winfield." The success of the series showed Stratemeyer that there were huge amounts of money to be made from going after the previously-untapped juvenile market, and he founded the Stratemeyer Syndicate in 1905.

The Syndicate operated under very strict guidelines -- Stratemeyer came from dime novels, he'd put in a lot of time at the pulp factory Street & Smith before striking out on his own, and he brought most of those iron-fisted editorial techniques with him. In particular, he retained all rights to the books and insisted that writers ghost all Syndicate-owned series titles under a house name like "Franklin W. Dixon" or "Carolyn Keene."

In later years Stratemeyer's daughter Harriet took over the business and she refined her father's editorial style into a rigid formula.

Harriet's formula worked over and over again, and really built the Stratemeyer book-packaging empire. Generally, this is how it went --

* Harriet Stratemeyer plotted and outlined story ideas and assigned them to writers to complete, much as the old pulp editors (and comics editors like Mort Weisinger and Julius Schwartz, pulp vets themselves) used to do.

* New series were first published in sets of three books called “breeder” sets.

* Chapters and pages should end mid-situation, to increase the reader's desire to keep reading.

* Characters should not age. (In some of the early series, such as the Rover Boys or Tom Swift, the characters did grow up and occasionally even marry, but sales dropped afterwards, prompting the Syndicate to make a rule that characters never marry or age.)

* Writers surrendered all rights and were paid a flat fee per story.

* All writers signed a contract promising to keep their identity a secret. Books were always published under a house pseudonym.

* Harriet Stratemeyer proofread and revised each manuscript and sent the book to a publisher, usually Grosset and Dunlap.

* Turnaround time was fast; generally just six weeks from conception and a story conference with a writer to the finished product. Deadlines were brutal, which is why the syndicate recruited such a large number of workhorse writers. (Usually guys hungry for work after the collapse of the adventure-pulp magazine markets.)

Probably the biggest success story of the Stratemeyer Syndicate would have to be teen detectives the Hardy Boys.

Frank and Joe Hardy, sons of private detective Fenton Hardy, are amateur sleuths who occasionally get embroiled in their father's cases, often having to rescue Fenton from smugglers or other such criminals. In addition, the young Hardys occasionally stumble into some criminal enterprise while on an innocent camping trip or something. And once in a while their father actually asks them to help out on a case. But until very recently -- in the latest incarnation of the series, Undercover Brothers, the boys are operatives of an agency called ATAC -- but except for that latest version, Frank and Joe Hardy had no official status, they were just regular kids who accidentally would get involved in an adventure and solve a mystery. (Rather like the way sweet old Jessica Fletcher accidentally stumbled over hundreds of murder victims over the twelve seasons of Murder, She Wrote.)

This series, launched in 1927, sold in the millions and continues to be very popular today as the rebooted Hardy Boys: Undercover Brothers. There have been several television series adaptations and even a Saturday morning cartoon from Filmation in 1969.

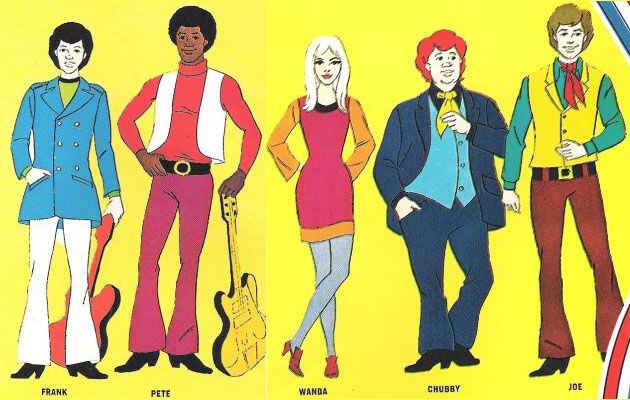

The cartoon re-imagined the Hardys as fronting a traveling rock band... each week they'd solve a crime and then do a song. (This was nothing to do with anything from Stratemeyer -- the success of Filmation's Archies mandated that every other cartoon group of crime-solving teens from that studio had to also be in a band.)

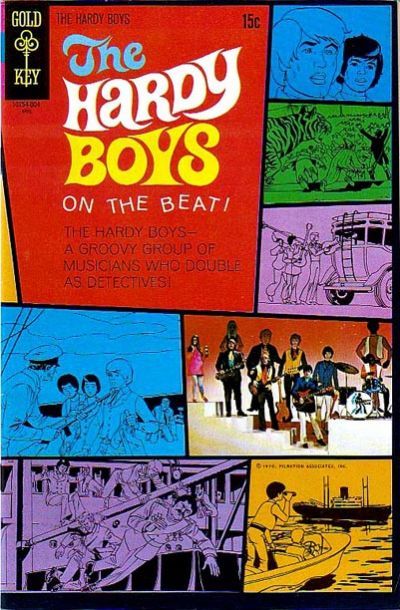

The cartoon in turn led to a short-lived comic book series from Gold Key.

In addition to the comic books, the cartoon also inspired another, very strange, tie-in product -- the release of two studio pop albums featuring live actors playing the cartoon characters. (I am pretty sure the young people in the photograph are not the actual musicians on the records, but no one seems to know who any of these folks were.)

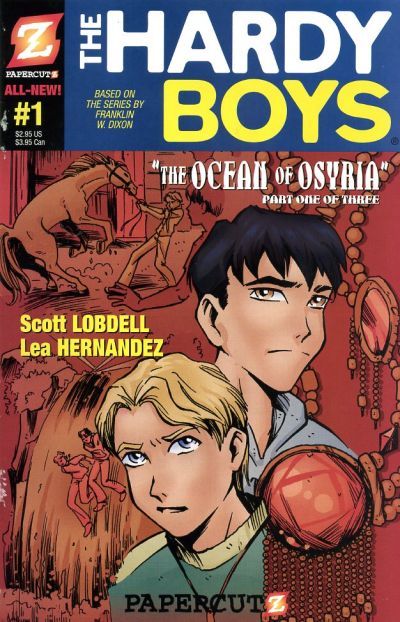

The Hardys returned to comics a few years ago, in a new manga-style series from Papercutz, scripted by Scott Lobdell and drawn by Lea Hernandez and Daniel Bendon.

The success of the Hardy Boys prompted Stratemeyer to launch plucky girl detective Nancy Drew in 1930 and she too has been going strong ever since, with millions of books in print and all sorts of tie-in merchandise -- not so much with comics or cartoons, but there have been five movies and a couple of live-action TV shows, as well as a dozen or so video/computer games.

Other series followed -- The Dana Girls, Biff Brewster, Kay Tracey. I was not aware, until doing some research, how hated these books were by schoolteachers and librarians back in the day. Juvenile series novels, particularly the formula books from Stratemeyer, were considered to cause ‘mental laziness,’ induce a ‘fatal sluggishness,’ and ‘intellectual torpor.' And no less an authority than the Boy Scouts of America published an article suggesting that reading series novels like the Hardy Boys were "Blowing Out Boys' Brains." Seriously. That was the name of the article. Thank God Frederic Wertham or Peggy Charren never got the bit in their teeth about these books or my childhood would have been completely screwed.

Disapproval hardly slowed the factory down, though. At the height of their success in the forties and fifties, there could be as many as a dozen releases in a month. The Hardy Boys, Tom Swift, Nancy Drew, along with lesser lights like Honey Bunch or the X-Bar-X Boys.

As for myself, when I was a kid I read the Hardy Boys and Tom Swift books and enjoyed them well enough, but they were only sporadically good. You couldn't count on them. (This was, I discovered years later, because dozens of different writers were ghosting them for Stratemeyer, so of course the quality blew hot and cold.)

Anyway, even as a kid my preferences tended more towards the oddball stuff like the Three Investigators or Danny Dunn, and far and away my favorite of any of these series are the "Christopher Cool, TEEN Agent" books. From the moment my nine-year-old self read the advertising copy in the back pages of a Hardy Boys book, I knew this was the series for me:

MEET...

CHRISTOPHER COOL / TEEN AGENT

as he plays the deadliest game of all––international intrigue––in America's newest exciting spy stories.

Christopher Cool and his Apache Indian roommate, Geronimo Johnson––sophomores at an Ivy League university––combine their campus lives with undercover assignments for a vital arm of U.S. Intelligence: Top-Secret Educational Espionage Network.

Expertly schooled in all the arts of espionage, the two daring TEEN agents work closely with red-haired Spice Carter, a clever coed agent, to thwart enemy spies in trouble spots throughout the world.

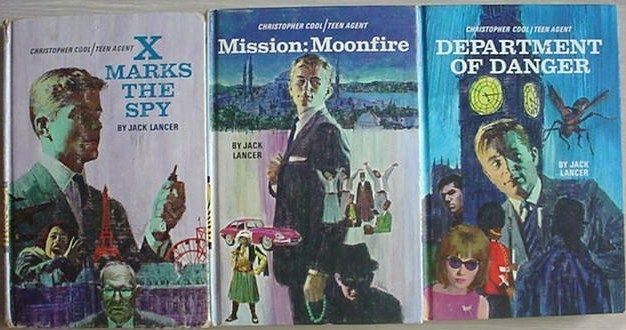

Soon afterward I saw a copy of Mission: Moonfire at a local Fred Meyer and it was relatively easy to wheedle Mom into picking it up for me. (After all, it was a book, not one of those awful comics, plus it sort of looked like the Hardy Boys and Mom knew they were safe.) X Marks The Spy and Department of Danger soon followed, and I was hooked.

The books were clearly inspired by U.N.C.L.E., but author "Jack Lancer" kicked the imagination and spectacle up a notch since he wasn't hampered by a television special-effects budget. Chris and Geronimo are equipped with more implausible gadgets than even James Bond's Q could have devised. A particular favorite of mine are the titanium-soled "rocket-hopper" jet shoes, able to blast Chris and Geronimo fifty feet in the air. (These are also handy for braking falls when a bad guy, say, hurls you off the Eiffel Tower, as an evil TOAD agent did to Chris in X Marks The Spy.)

The premise is similar to UNCLE or James Bond, but the Stratemeyer house rules still applied, so things were strictly G-rated. Keep it moving, lots of action but no real violence, and especially, no kissing. (Despite the presence of gorgeous female TEEN agents like the aforementioned Spice Carter or smokin'-hot Asian co-ed Yummi Toyama, no one ever got up to any hanky or panky.)

There were six volumes of the Christopher Cool books. As usual with a Stratemeyer series, the first three were put into wide release almost at the same time, which is why it was easy for me to get hold of X Marks The Spy, Mission: Moonfire, and Department of Danger when I was a kid, and fairly easy for an interested collector to do so today, as well. But it's taken most of the intervening forty years for me to track down the second three.... well, not in a continuous effort, but it's been one of those minor bookscouting quests I pick at when Julie and I are on our expeditions. The print run on books four, five and six was much smaller and usually dealers want ridiculously high prices for them.

However, I finally managed it, and it pleases me to report that the second three in the series are as wonderfully delirious and adrenaline-fueled as the first three. Once again, I can't top the ad copy, so here you go.

Ace of Shadows: When enemy agents try to snatch the secret files of Count Dietrich von Kronstein––who has helped refugees escape from behind the Iron Curtain to the West––the count seeks TEEN's help. The U.S. intelligence agency dispatches its two most skilled agents, Chris Cool and his Apache pal Geronimo Johnson, to the count's castle in Bavaria. They arrive in time to witness his funeral! During the services a blowgun dart narrowly misses Chris, but kills a diplomat from the Arab country of Marak.

What happens next catapults Chris and Geronimo into a terrifying race to Marak to East Berlin and back to Bavaria, to prevent an international bargain which could destroy the free world.

The TEEN agents match wits not only with the deadly espionage organization TOAD, but also with the elusive and feared Red spy known as the Ace of Shadows.

Heads You Lose: When the shrunken heads of two CIA agents are delivered to TEEN headquarters, Chris Cool and his Apache Indian fellow agent, Geronimo Johnson, are ordered to Ecuador, to apprehend the sinister donor, a revolutionary known as Cascabel the Rattlesnake. A high practitioner of voodoo, Cascabel has stirred the head-hunting Jivaros into a frenzy––part of his monstrous plan to overthrow the government.

In Quito, Chris and Geronimo are hired by an Argentine playboy, Fernando Rios, to transport medical supplies to the disease-stricken Jivaros. Suspicious of Rios, the TEEN agents risk their lives to ferret out the Argentine's real motive and at the same time hunt down the satanic Cascabel.

Mysterious pursuers in the jungle, weird pagan rituals, and voodoo curses add up to exciting and gripping adventures in this spy thriller.

Trial By Fury: Tape recordings of kangaroo trials, in which world leaders are condemned to death, speed TEEN agents Chris Cool and his Apache Indian partner, Geronimo Johnson, to Indonesia on a fantastic espionage mission. Their orders: to track down a fanatic Oriental assassin.

Dramatic developments in Djakarta on the island of Java lead Chris and Geronimo on a dangerous island-hopping chase to Komodo Island, inhabited by fierce dragon lizards twelve feet long. The exciting hunt backtracks to Djakarta, then takes the TEEN agents to Holland, and finally to Singapore, where the intrigues of the sinister assassin threaten their lives.

Evil Counts in Bavarian castles! Weird pagan rituals! Fanatic Oriental assassins! World leaders kidnapped and condemned to death by Komodo Dragon! Really, can't you just feel the AWESOME?

I assure you the books are every bit as much fun as they sound. Not quite as goofy as, say, Derek Flint or Austin Powers, but nevertheless written with tongue firmly in cheek, they're a wonderful way to kill forty-five minutes or so. The second in the series, Mission: Moonfire, is still the best, I think, but any of them are a good time.

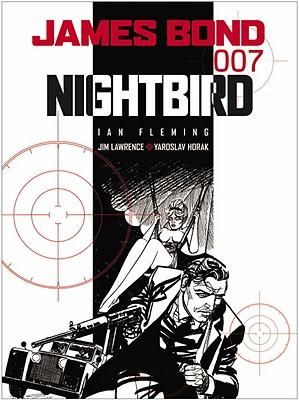

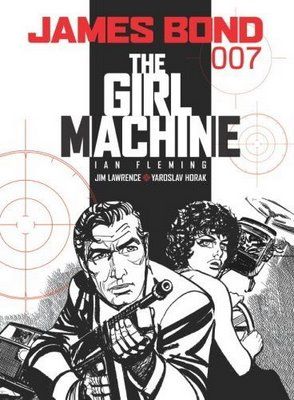

The Stratemeyer Syndicate had a strict rule -- well, truthfully, as I explained above they had MANY strict rules, but the one I want to mention was that all their authors had to use a house pen name. What I did not know until this week was that "Jack Lancer," the creator and author of Chris Cool, was in fact a comics guy. He was Jim Lawrence, who -- after the Christopher Cool gig failed to take off in 1969 -- took over as the writer of the James Bond newspaper strip, currently available in these swell collected volumes from Titan Books.

In fact, not only did Jim Lawrence write the Cool series, but he ghosted a lot of other books for Stratemeyer, as well -- including, I found to my delighted astonishment, the Hardy Boys and Tom Swift books that I remember as being "the good ones." Turns out I wasn't a fan of the series so much as I was a fan of this particular writer. I don't think I've been this floored since I discovered that most of the series paperback writers I loved in the 1970s were all Ron Goulart.

Sometimes I think it's a shame that "Christopher Cool, TEEN Agent" didn't catch on as a series. But then again, maybe not. I love me some Chris Cool, even today, but on the whole, I think I'd rather have the Bond comics. Either way, though, finding out that several of my favorite childhood authors were all actually the same man, Jim Lawrence, is kind of a -- dare I say it? -- cool fact to discover.

See you next week.