Last week, in Part One, I talked a little bit about what the comics and super-hero landscape looked like when I discovered them at the age of six. This week, I want to jump forward ten years, to what the world of comics looked like to me when I was sixteen.

*

"Potential" was a word I was heartily sick of by the time I was a junior in high school. It seemed like that was all anyone ever said to me -- Greg, why are you wasting your time on this stuff? You have so much potential. I had pretty much made up my mind that when an adult started off by talking about "potential," it was a way of saying, I want you to pay attention to what I like now, and maybe later we'll look at what you like.

Delayed gratification was not something I'd ever been good with, and there was something so maddeningly condescending about being told, over and over, that if I wanted to write then I should write this way, or that if I wanted to draw I should do these subjects. I didn't need advice about what kind of thing I should be doing. I needed technical help; I desperately wanted someone who could help me get what was in my head out on to the paper somewhere.

I needed, most of all, to not feel quite so much like a lonely voice in the wilderness, to get some kind of validation for the kind of work I did want to do. The books and comics that I admired WERE worthwhile, damn it! It wasn't TRASH any more! Why did everyone still think it was all Adam West and Biff Bam Pow? Holy misrepresentation, Batman!

The truth of the matter is that in the late 1970's, comics were all about unrealized potential, too.

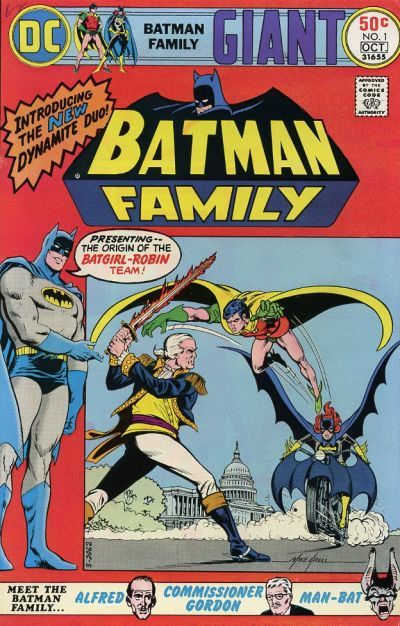

The decade had started with such amazing promise. O'Neil and Adams on Batman. Thomas and Colan on the Black Widow. Englehart-Brunner Doctor Strange. Mike Grell's groovy Legionnaires. It seemed like all over the funnybook landscape, superheroes were getting a hip, happening makeover. Even Robin -- the TEEN wonder these days, thankyewverymuch, shove that up your Holy whatever -- got a little more respect and a coolness upgrade.

DC's 52 Pages -- Bigger and Better gave way to the 100-Page Super Specataculars, which combined the new hip relevant stuff with my beloved archival 80-Page Giants. Those 100-page monsters still stand as some of my favorite comics of all time.

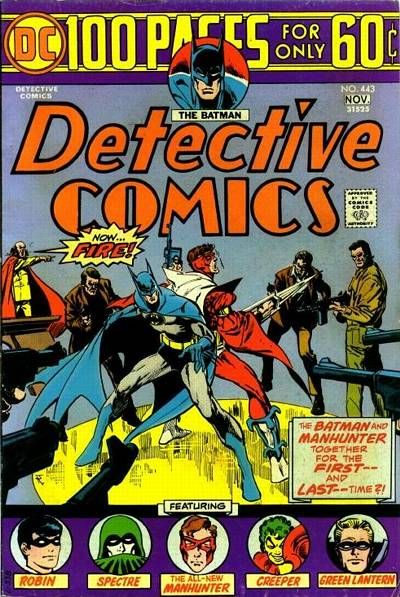

The trouble was, nothing lasted. I absolutely loved Archie Goodwin's work on Detective -- to this day, "Goodwin and Simonson's Manhunter" is usually the answer I give when my students ask me what my favorite comic is. But Goodwin's entire editorial tenure on 'Tec only lasted a year or so -- seven bi-monthly issues. That was followed by Wein and Aparo's "Bat-Murderer" under Julius Schwartz, another seven-issue arc that I liked all right (nowhere near as good as the Goodwin books, but it was okay) but halfway through the arc Aparo moved on and they quit doing the 100-pagers. The art was finished out by Ernie Chan, who again was okay but he wasn't Jim Aparo, and even Aparo wasn't a patch on the greats that had been on the book under Goodwin -- Alex Toth, Howard Chaykin.

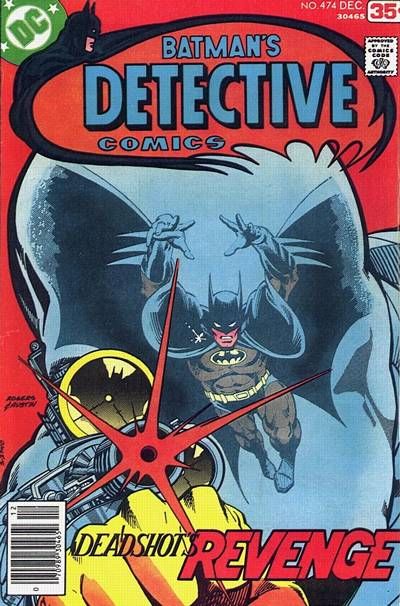

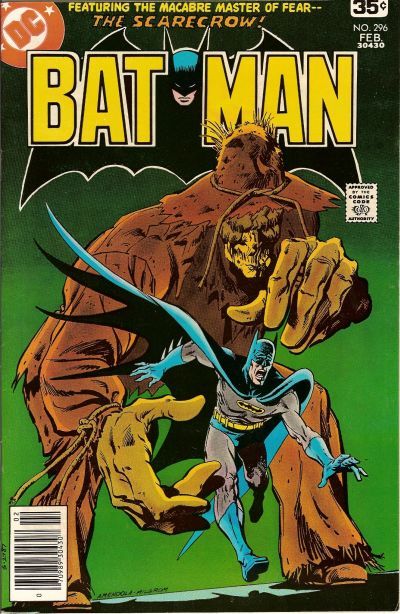

This was a pattern throughout the 70's -- get excited, get disappointed. The Batman titles, especially, blew hot and cold. You never knew when you were going to get something awesome like Englehart and Rogers...

...but the best you could hope for was six or seven issues. As soon as you started looking forward to the books again you'd get some pedestrian gimmick story by David V. Reed.

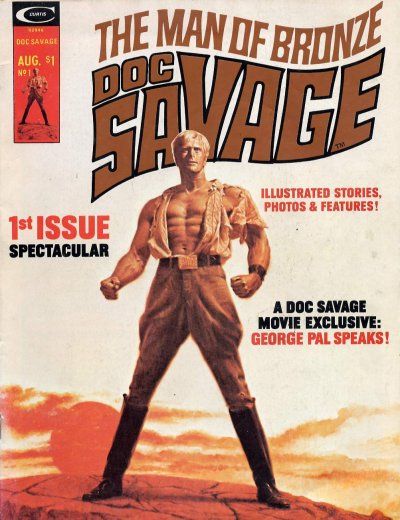

That pattern of brief excitement leading to an inevitable letdown colored everything in the mid-to-late 1970's, it seemed like. Another example was how I got all excited over the idea of a Doc Savage movie when I heard about it-- Doc, by George Pal! The Forbidden Planet guy! This was SO GOING TO ROCK!

And... well, it didn't. I've come to appreciate the movie quite a bit more since then, but at the time I was bitterly, bitterly disappointed. The magazine was pretty cool (and it's still the best comics version of Doc, I think) but, again, seven more issues and then it was over.

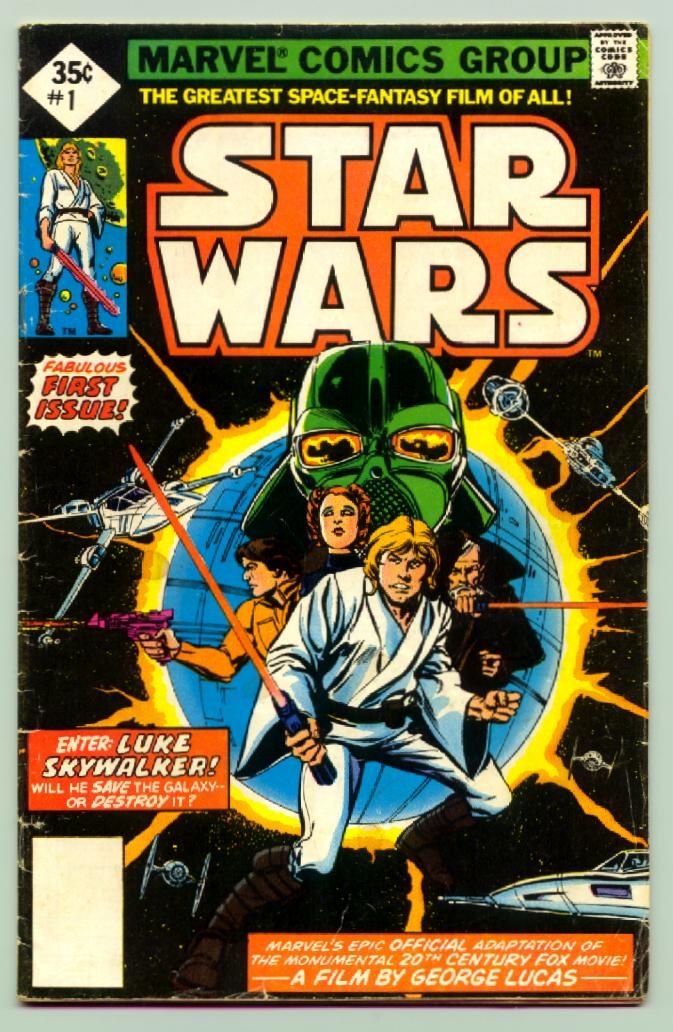

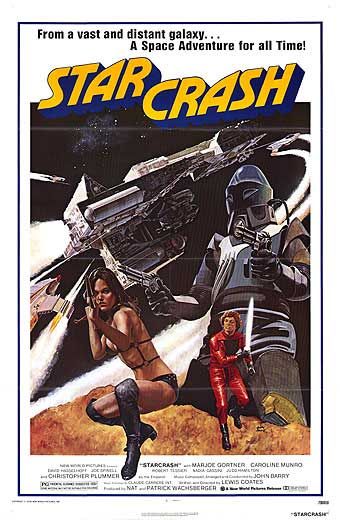

In 1977 the entire geek landscape changed when the cultural nova called Star Wars hit.

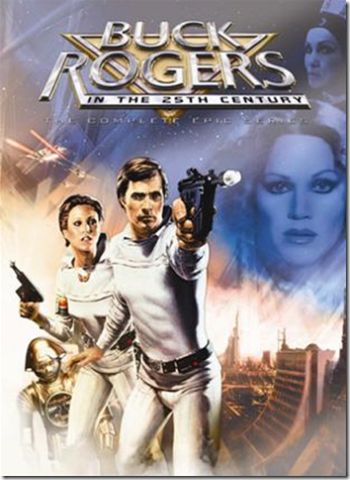

Except it really didn't. Not as much as we THOUGHT it was going to. What we got was a lot of people rushing stuff into production hoping for a little coat-tail action.

Stan Lee managed to somehow wheedle Universal Studios into a contract for a bunch of made-for-TV movies based on the Marvel characters. That was pretty exciting news -- until we SAW them.

It didn't matter how much I tried to explain to my Mom and Dad that the comics weren't LIKE this... they dealt with Important Issues, they were Relevant and Meaningful Literature. There was nothing in the film or TV adaptations of the 70's that changed their position. It was still crap and a waste of my time -- and as far as these TV efforts were concerned, in my heart I knew they were probably right.

Although I am still very fond of the Bill Bixby Hulk series that resulted from that deal, and I have a soft spot for the Phil DeGuere Dr. Strange pilot, my folks were right; I couldn't really put any of this stuff in the plus column. Even the charming Lynda Carter Wonder Woman was too smirky for me, back then. The comics-get-respect thing still wasn't happening the way we thought it would.

Instead it felt like everything was in some sort of downhill slide. My favorite books at Marvel were in such sad shape by 1978 I ended up dropping them.

I felt ridiculously sad over it. End of an era.

The landscape was changing. Comics were getting thinner all the time and series were getting canceled left and right, and the prices kept going up. You look at a DC book published in '77 or '78 and it feels more like a brochure than a magazine... a sad, anorexic thing that cost almost three times what it had a decade previously.

But my tastes and attitudes were changing too. I was less driven about finding an escape hatch from my real life (though that was still pretty sucky) and more and more obsessed with finding a way to DO this kind of work, to write and draw my own stuff. It wasn't enough to live in an imaginary world any more -- I wanted to create my own.

I knew I had some writing and drawing chops -- there had been enough teachers who handed out a few grudging compliments (before the "wasting your potential" lecture) that I knew that I could do something. What I needed was an outlet. I just wasn't sure what that might be.

Art class at school wasn't cutting it, or creative-writing class, or any of the other school-type outlets. It probably didn't help that I was arrogant and snide and my temper was on a low-level simmer even on my best day. No one can work a persecution complex like a sixteen-year-old kid. There was enough truth to it, at least where home was concerned, that I had plenty of fuel for all that rebellious anger. Goddammit, why didn't anybody GET IT!??

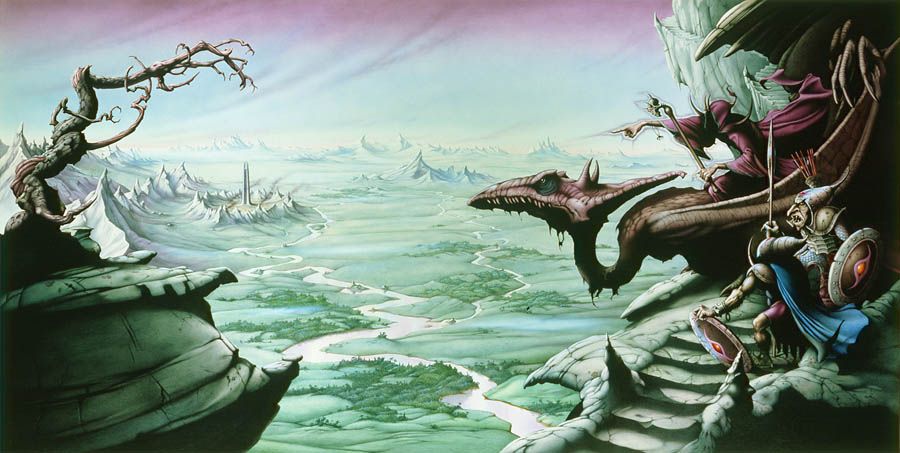

I had found a few kindred spirits. My friend Joe, in particular, was an accomplished guitarist and introduced me to the wonders of artists like Rodney Matthews and Roger Dean.

There were times I ended up buying records I hated because I was so in love with the cover art.

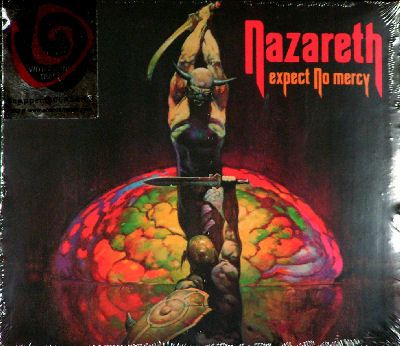

I fell for this one just because it reminded me of Robert E. Howard's "Tower of the Elephant." (Yeah, I know, it's a dorky reason. But own up. Show of hands -- how many out there bought that lame Nazareth album to get the Frazetta cover?)

Slowly I was forming a sort of cultural aesthetic; the stuff I liked had a rock and roll attitude, a cutting-edge graphics sensibility, it was Serious (no Biff! Bam! Pow! Adam West-style smirking allowed) but still swashbuckling enough to be fun... that was the stuff that set me on fire. That was what I aspired to.

But how to do it?

Into this roiling subconscious I-Want-To-DO-Something need I was carrying around, came my sudden discovery of Jim Steranko.

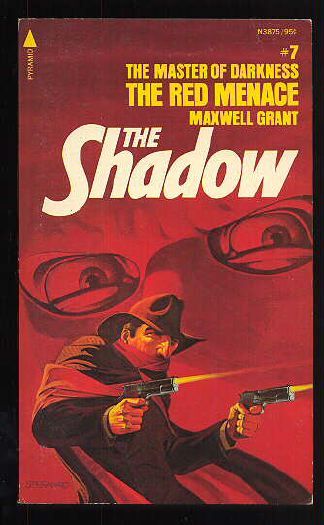

It had started with the Pyramid reprints of the Shadow pulp novels that Steranko was doing covers for.

I had to do a speech for a class, illustrated with posters; and I thought I'd do one on the history of the Shadow. I had two great posters from Mike Kaluta but I needed more of them. So I set out to re-create the Steranko covers at poster size, with markers, for this class project.

And it worked. Just copying the Steranko Shadows at that larger size I learned all sorts of things about color and shadow and form, and I learned how to do it with impact. I ended up delivering that speech at various school competitions throughout the state and even winning a couple of awards, and I am convinced it was the posters that sold it.

At the same time, I and my fellow high-school refugee Joe had taken to driving into downtown Portland a lot. That was where all the good record stores and book stores were to be found, and with Joe a newly-licensed driver there was no longer the need to sneak around or lie about taking a bus into the city. (My mother had an irrational fear that going into the city would get me in terrible trouble. This was obviously silly -- I never needed to leave the neighborhood to accomplish THAT, there was a park at the end of the block where we could drink stolen beer and smoke dope.)

Anyway, I'd just holler that I was out with Joe, back later, and off we'd go. (Years later, Joe commented wryly to another friend of ours, "Picking up Greg at his house always felt like driving the getaway car.")

One of our frequent stops was Looking Glass Books on Southwest Taylor, between 4th and 5th. (It's still around -- it's over on the East Side these days, but it still has that indie sensibility from what I can tell.) That place was a gold mine -- it was where I could actually find all the stuff that I'd only seen advertised in my comic books.

That was where I found probably what were the two most influential publications on me in the 1970's, they literally shaped my career path. And both of them involved Jim Steranko.

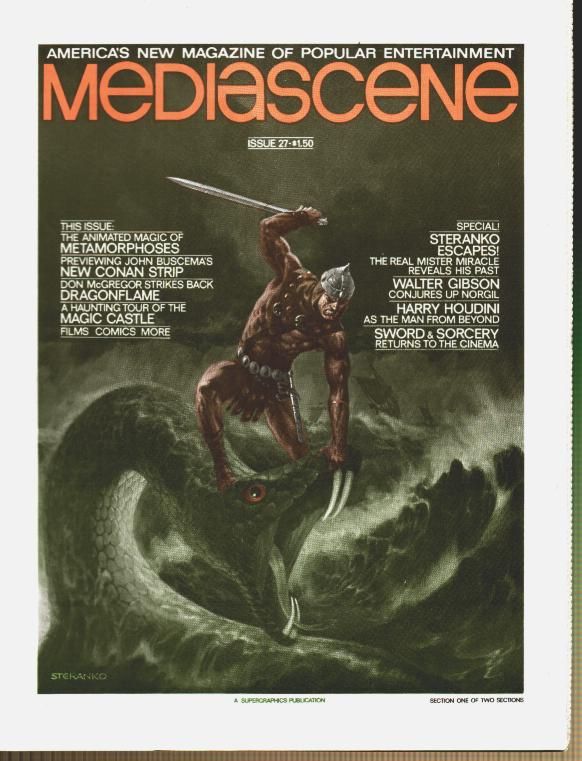

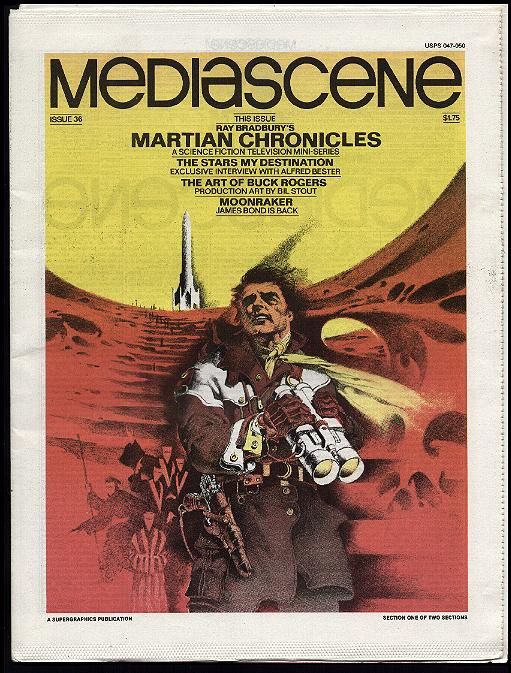

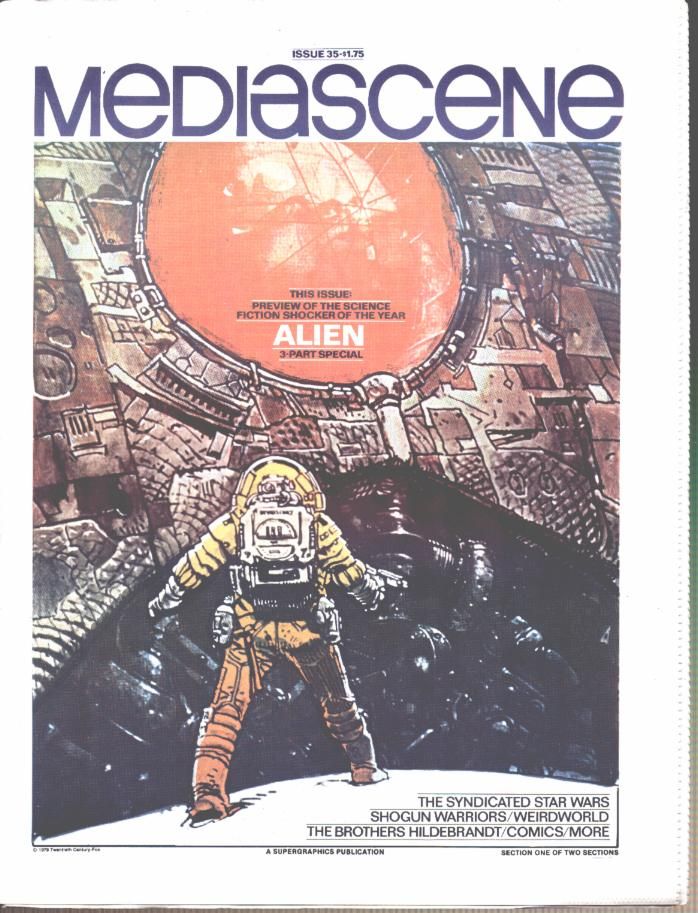

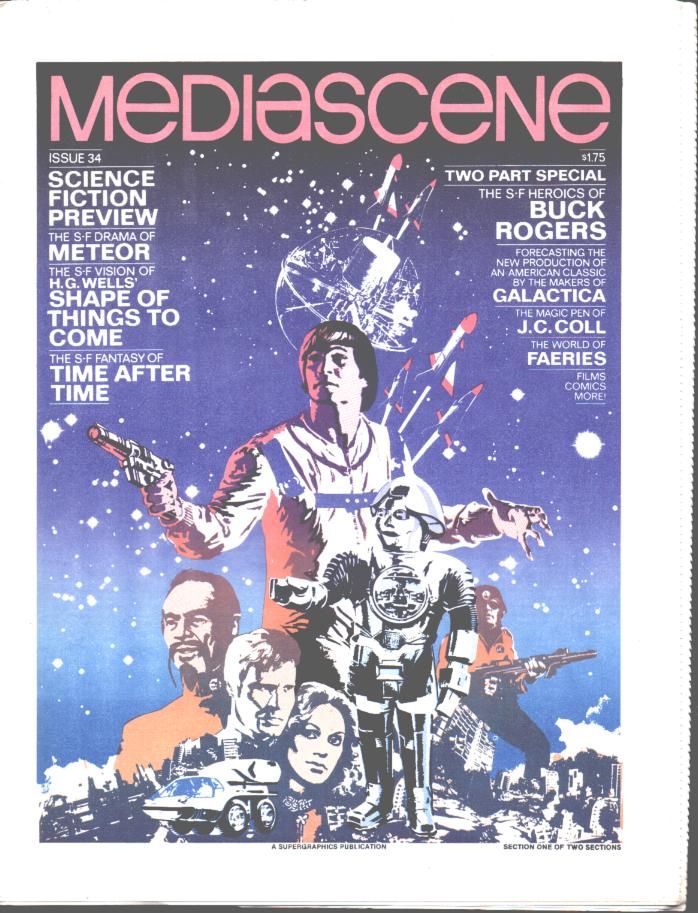

The first one was Steranko's MediaScene.

This was a tabloid that covered not just media, but geek media -- MY stuff. And because it was Steranko's baby, the design work was extraordinary.

No matter how inanely-written the puff pieces might be, the package always looked gorgeous.

Often the paper itself was way cooler than the crap it was covering, but that was part of why I loved it. It was the aesthetic.

Yeah, it was basically a fanzine, but done with amazing skill. And I'd never seen a fanzine before. It gave me that validation I hungered for -- I wasn't the only one that loved this kind of thing. Most of all, artistically it had that same movie-poster graphic sensibility, the same techniques I'd been trying to teach myself doing those Shadow posters.

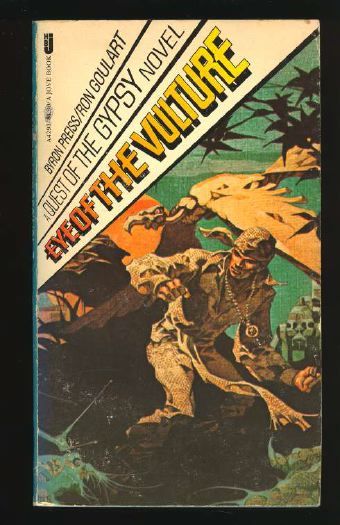

And around the same time I found Weird Heroes. I've talked a little about these books here before -- another 70's effort that stuttered to a halt with volume eight, sadly, with several promised follow-up projects left unfinished.

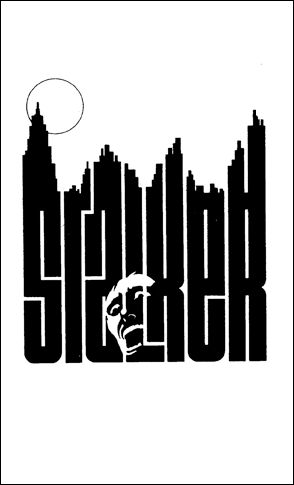

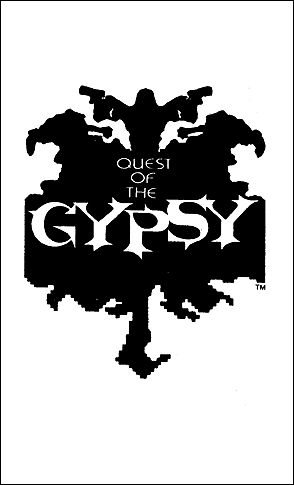

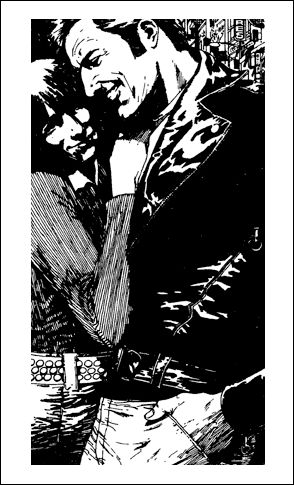

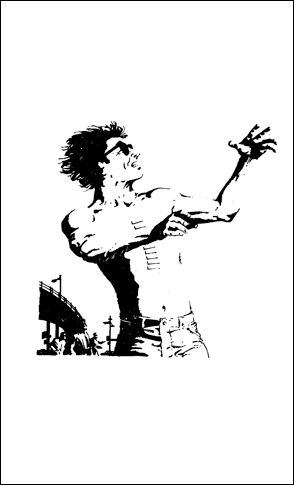

But at this point they were going strong and volume one, especially -- another stunning piece of Steranko design -- served to crystallize my ambition.

I wanted to do stuff like THIS.

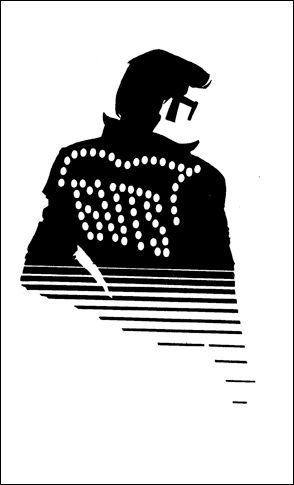

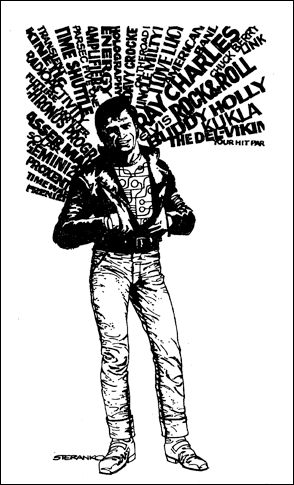

Steranko had done these amazing logos for every individual entry. And he'd also illustrated a couple of them, and the illos he'd done for "Guts the Cosmic Greaser" demonstrated a pen-and-ink technique I thought maybe I could learn.

This was a goal I could reach. Well, maybe. But by God I was going to try -- immediately all my drawings were done in this style, that spot-black rendering with lots of white space.

Actually, not so much the rendering itself but the method, the high-contrast no-gray-tones style that could be duplicated with markers. Markers were the kind of art supplies I could afford.

Joe and I had both enrolled in Journalism, my senior year in high school, and we found it to be a continuing frustration. The school paper was a tepid thing, at least by our punk-rock standards, and we were continually butting heads not just with the teacher but even with our classmates. At one venting session in the cafeteria another friend said to us, "You guys should start an underground newspaper."

Hmm. We should. But how would we do it? What would it look like?

I knew it would look a lot like MediaScene. But with fiction, too, and stuff about bands we liked. "Something people actually want to f'n READ," was what Joe and I told our friends, smugly.

Joe and I had attended a one-day SF show at Portland State, a desultory little affair with a couple of writer's panels and a showing of Fritz Lang's Metropolis. (Put on by the Portland Science Fiction Society -- "PorSFiS," they kept calling it -- little did we know that this one-day event would eventually mushroom into the Northwest's SF institution OryCon.)

Of the writers that were there, I remember Vonda McIntyre and John Varley (both of whose books I made it a point to track down.) But for Joe and I, the star that day was a young John Shirley, who reminisced briefly on stage about trying to get an underground paper going at his high school. THAT set us afire.

Shirley exuded almost a godlike cool as far as we were concerned -- after all, not only was he a published SF writer but he also sang lead in the punk band Sado-Nation. We were awed, but not too awed to corner him in the hallway and ask him how he'd done his underground high school thing and what it took. Mostly he exhorted us to just Do It, and the hell with what anyone else said.

Thus encouraged, I marched down to the principal's office the following Monday and put it to him. My friend Joe and I weren't satisfied with the way the school paper was being done and we wanted to do our own. Would we be allowed to distribute it on school grounds?

Mr. Schell -- a much nicer man, really, than he ever got credit for with students -- listened to what I had to say, how we wanted something with art and fiction and music reviews "that people would actually READ!!" and when my rant finally ran out of steam, he regarded me thoughtfully over steepled fingers.

"What if the school paid for it?" he asked.

I blinked. I was telling him his school paper sucked! Was he agreeing with me? Had he not been paying attention?

"I'm serious. This sounds like something we would be willing to support. Find a faculty adviser to sign off on this and we would be willing to publish it."

I had been ready for almost anything but this. However, it didn't take me long to agree. We were BANKROLLED!

It took a fair amount of fast talking to get our journalism teacher to agree to act as advisor; I suspect he was just happy his two problem children were finally fully engaged with something. But he agreed to co-sign our folly.

The resultant magazine, Visions, only ran one issue, and it took Joe and I months to get THAT out. It taught me... well, it taught me what an enormous pain in the ass being an editor was, for one thing. Herding cats would have been easier.

Still, we were proud of what the finished 'zine looked like. We'd recruited our friend Marion to design a cover logo and do a couple of illustrations, our friend Todd did the photos, and we had a series of stats shot of a bunch of student art and printed that in a section called "Gallery" that I wanted to do as a regular feature. (This was in the Dark Ages before high-speed photocopying; Xerox copies still came out wet and smelling strongly of solvent back then.) We had an interview with a local actor that was touring the high schools with a one-man version of Oedipus (using authentic Greek theatre masks), a feature on a local band (the TuTu band, a sort of low-budget rock cabaret group that was doing elaborate stage shows) and I was determined to find some student short fiction as well. Finally I wrote one of my own, a story about a guy that lives in a society so repressive that he retreated into a coma where he lived out his own fantasy daydream. Well, you write what you know. I used a pen name because I didn't want it to look like a vanity publication.

In the middle of it all I recruited my friend Janet from the debate squad who helped me somehow organize this mess into a coherent eight-page tabloid (mostly she transcribed and edited the interview tapes, something I'd never have time to do on my own) and finally in one crazed night alone in my bedroom I sat there with the strips of typesetting and the stats and a black marker (to do the page border lines and title boxes) and pasted up the entire thing myself.

Reaction was... mixed. Our art teacher thought there was too much science fiction. Our journalism teacher thought we came off too smug in print. (These were both valid criticisms, I think.) My parents were befuddled. My English teacher loved it, and gave me the backhanded compliment that if I put that kind of effort into my actual studies... well, you know how that song goes. The vice-principal wrote us a nice critique that had a lot of good points.

And Mr. Schell called me into his office to tell me sternly that he'd had a couple of calls about the profanity in the story.

"How many?" I demanded. "Our advisor signed off on it. That was the deal."

Turned out it was two calls.

"We've got, what, a student body of 1200?" I snapped. "So that's a potential 2400 parents making angry calls. And you got two. So 2398 thought it was all right." I was just going into my windup. My next demand was going to be that he bring those parents in and I'd talk to them myself. (And they would learn to fear my righteous wrath.)

Mr. Schell waved me off. (In retrospect, having been on the other end of this conversation with my own students in recent years, I can see that his heart probably wasn't in it.) He agreed that two calls wasn't very many, but still, he'd prefer not to have any at all.

That was where we left it, but the next day we discovered it was a moot point. We'd overspent. They'd only fund one. The first issue of Visions would also be the last.

But at least, now, I knew I could DO this. Wait'll I hit college, baby!

*

I'm sorry I don't have a copy of this thing today; I think my English teacher saved one, it's probably somewhere in her attic. And Joe might still have one. (This is, by the way, the same Joe that drops by here once a year to wish me a happy birthday. Joe, if you're out there, send me a scan, would you?)

The other footnote is how delighted I was, a little while ago, to see that John Shirley was a Bat guy, too. Who knew?

See you next week with Part Three.