As a Marvel Comics editor for more than a decade, Carl Potts mentored and worked with many young creators starting in the industry, including Jim Lee, Arthur Adams and more. At the same time, Potts worked as a writer or artist on a number of books, including most famously a long run writing and doing layouts for "Punisher War Journal," and writing his co-creation, "Alien Legion."

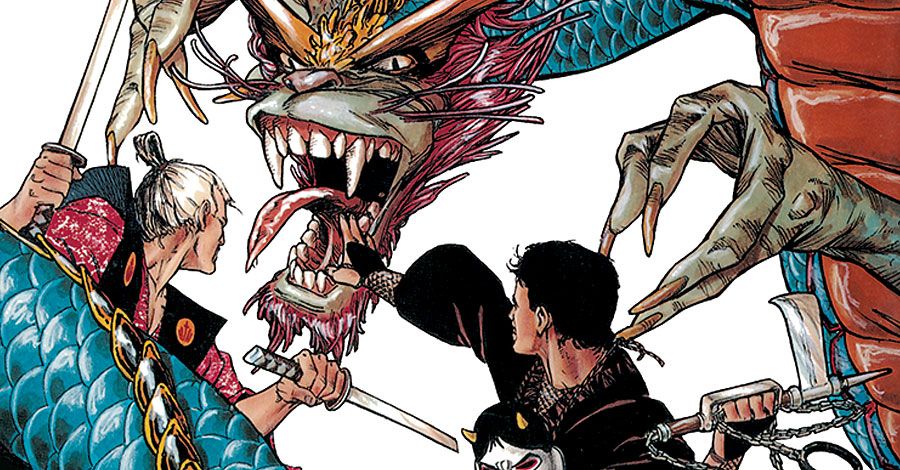

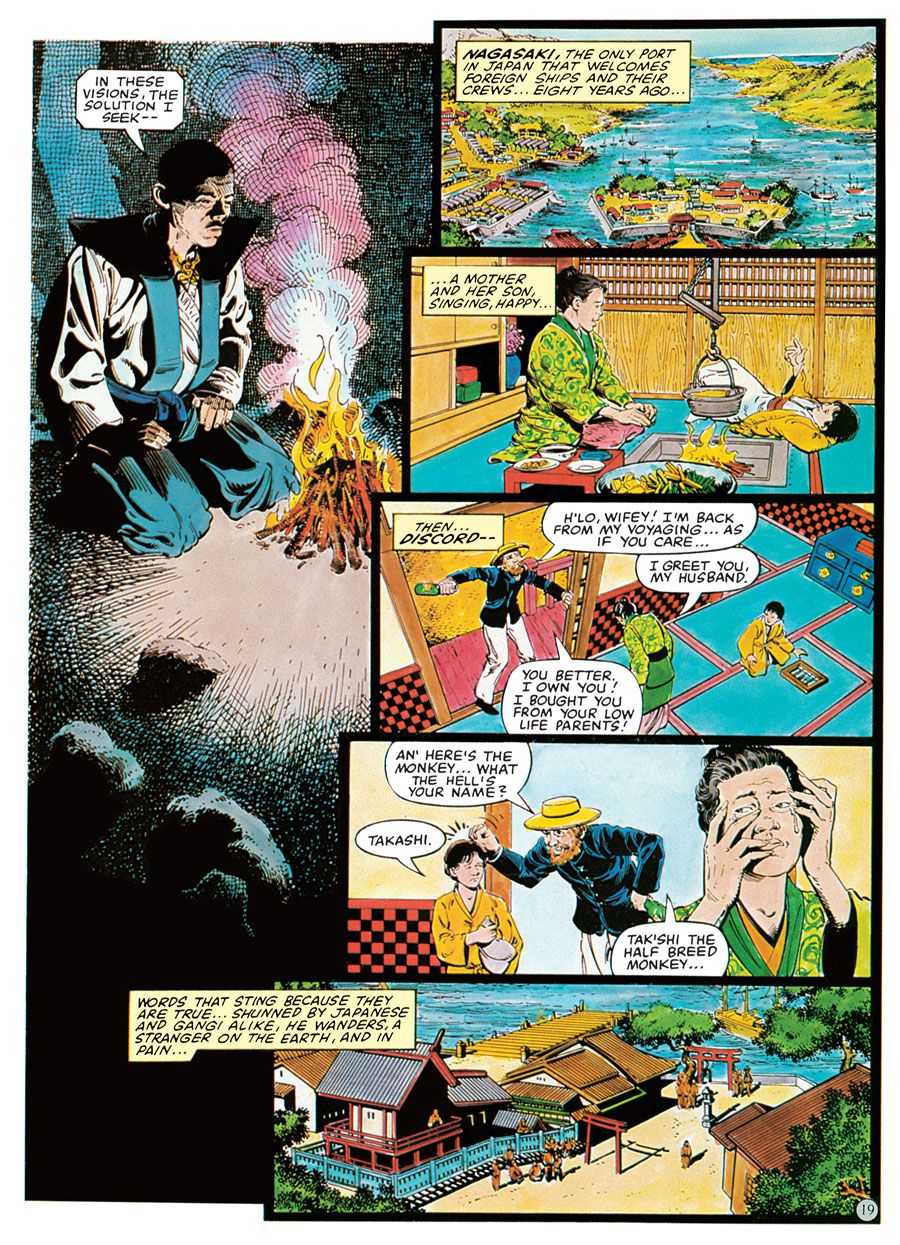

One of Potts' first comics projects, "Last of the Dragons," originally published in "Epic Illustrated," has been repackaged and released by Dover Books. The story, written and illustrated by the comics veteran in the early '80s, has a unique take on monks, ninjas, samurais and dragons as a group of monks in 19th Century Japan have trained dragons and plan to bring them to America. The human characters are treated seriously, with actual sources, and the look and background of the dragons comes from Japanese mythology.

Potts spoke with CBR News about returning to his first major creator-owned work, the joy of professional naïvete when putting together the series' all-star creative team and his hopes to a live-action version become a reality. The longtime editor also reminisced over his time working with up and coming creators, including Jim Lee and Arthur Adams, and the projects he's working on now.

CBR News: You pencilled and wrote "Last of the Dragons," but it was scripted by Denny O'Neill, inked by Terry Austin, colored by Marie Severin and edited by Archie Goodwin. At the time, were you thinking, "How do I get arguably the most talented people in comics to work on this?"

Carl Potts: As a new comics creator at the time, getting all of these amazing people to work on "Last of the Dragons" was so simple and relatively easy that I assumed this is how things happened all the time. I wish getting a movie made was as easy as putting the original "Last of the Dragons" team together!

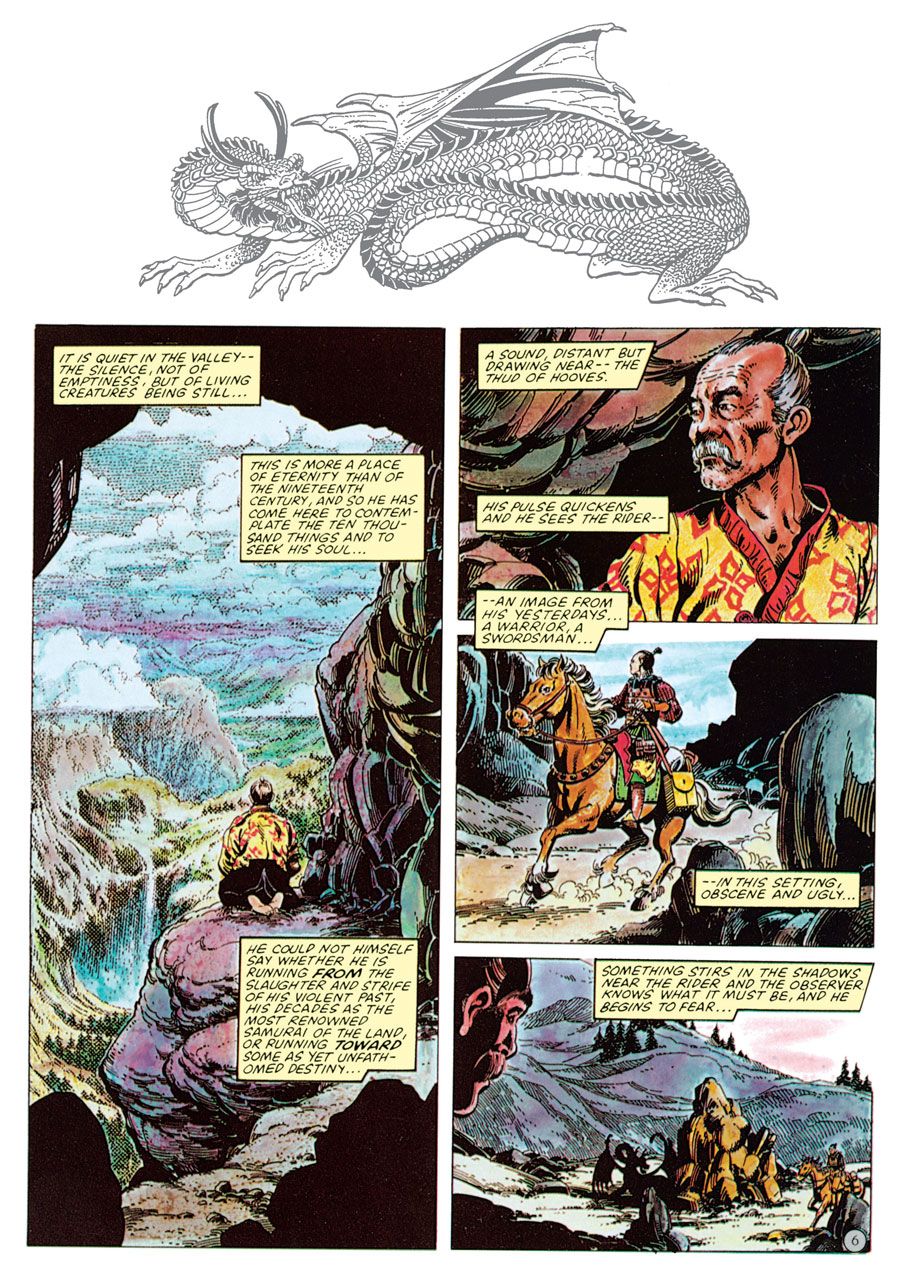

With publications like "Heavy Metal," Marvel's "Epic Illustrated" and a number of small press direct market publishers appearing, the ability to publish stories across a wide range of genres was growing. I'd been slowly pulling the plot for "Last of the Dragons" together. It was a result of a combination of my interests in action/fantasy and the Japanese part of my heritage (my maternal grandmother was Japanese). I was going to the Bleecker Street Cinema every week to watch Samurai films, buying lots of books on Japanese history and martial arts and taking Karate (artist Val Mayerik, a Karate black belt, taught the classes). Later, I got into studying Aikido and Ninpo.

After working out the basic plot for "Last of the Dragons," I did some presentation art to try and line up collaborators and a publisher. Terry Austin, also a fellow Continuity Studios freelancer, liked what he saw and agreed to ink the project. At the time, Terry was rapidly becoming one of the most in-demand inkers in the business. That was the first big piece of the team personnel puzzle and helped give the project credibility.

When I had the first chapter penciled, I pitched "Last of the Dragons" to Archie Goodwin, editor of "Epic Illustrated" and probably the most universally liked and respected figure in the comics business. Archie liked the pitch and agreed to begin running the series after I had several more chapters completed. I was confident in my plotting but unsure of my scripting skills, so I had the naive audacity to ask Archie if he'd like to supply the dialog over my plot. Archie politely suggested I find another experienced writer to do the finished script. My two favorite writers at the time were Archie and Denny O'Neil, so I walked over to Denny's office at Marvel, pinched the project and asked him to script it. "Last of the Dragons" immediately grabbed Denny's interest and he came on board.

On a roll, I also easily got Marie Severin and Jim Novak to join the team. At the time, I was very happy that this crew of great talents had agreed to collaborate on the project. However, I was not fully aware of just how rare it was to have everything break my way so quickly and easily when putting a highly respected team together. Today, it boggles my mind.

What it was like writing the book with O'Neill and how did it change during the scripting stage?

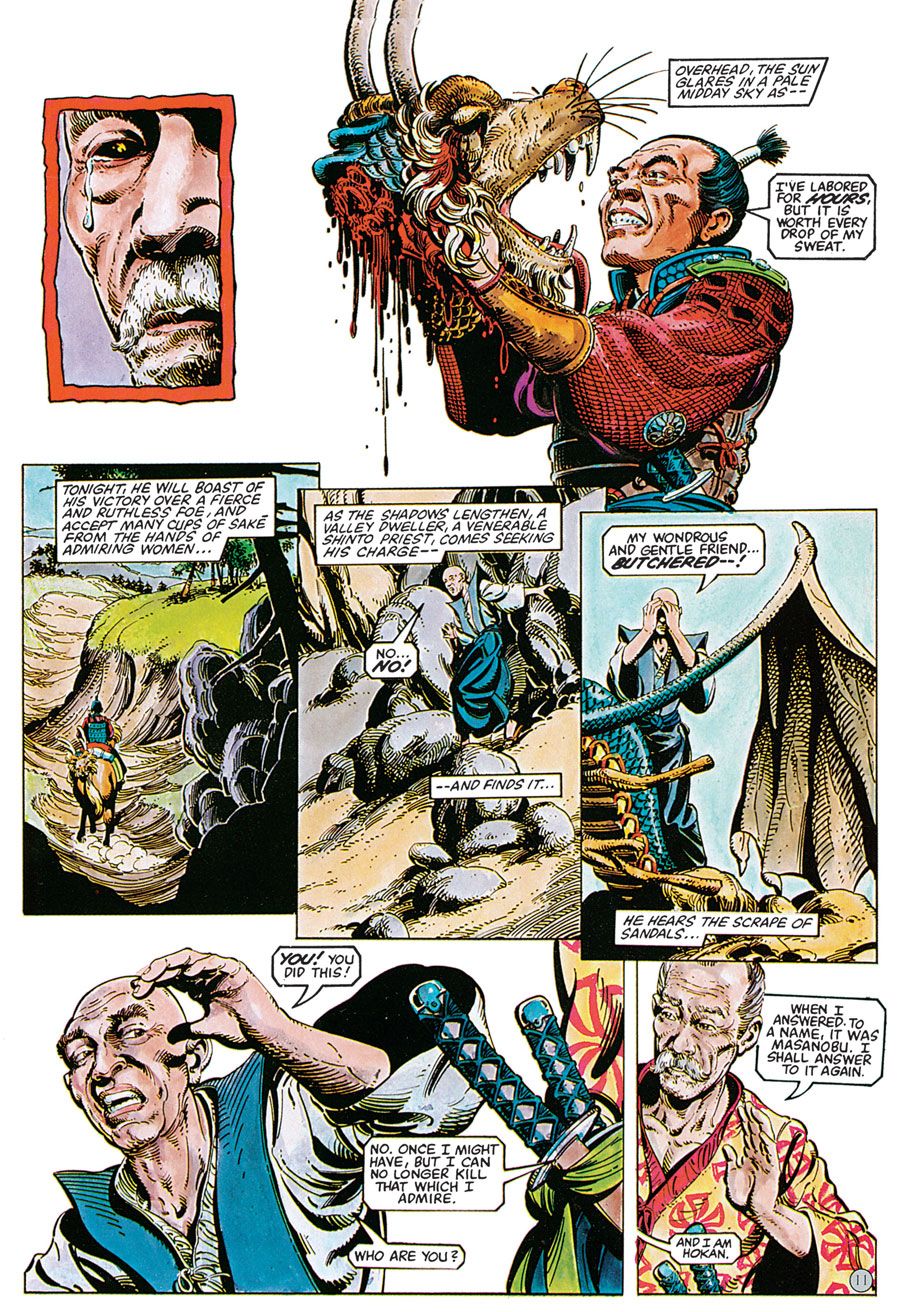

I don't recall Denny suggesting or making any changes to the plot. Early on, I'd given him the plot of the whole series. Every time I finished penciling a chapter, I'd send it to Denny and, soon after, he'd send me the finished dialog and captions. He'd often add, or emphasize, aspects of the story, making it much better than what I'd originally had in mind. Masanobu's thoughts in the first chapter and a good example. Denny brought out more of the philosophical themes than I'd indicated in the plot.

What was it like putting together the piece for the magazine and working with Goodwin, in particular?

As long as he liked it and thought it would work for "Epic Illustrated," Archie Goodwin was open to work from everyone from established pros to relative newbies like me. He was very good at making suggestions on how to make a project better but rarely utilized those skills. When needed, he could make suggestions for much-needed improvements in work in a way that the freelancer's feelings weren't hurt. On creator-owned material, I think Archie felt that if he liked a project enough to buy it, he should then let the creators do their thing.

I don't recall Archie, or his assistant, Jo Duffy, making any suggestions for changes to the art, story or script. Archie was slightly perturbed when I added an extra page -- the last page of the story -- to the final chapter without getting clearance from him first. That extra page threw off Archie's line up for that issue. The magazine had a mix of color and black and white page signatures. My extra color page threw a monkey wrench into that issue's line up. After looking at the extra page, Archie decided it was indeed important to include and reworked the issue's page set up to accommodate it.

When delivering either chapter 4 or 5 to Archie, he slowly read the pages while I waited. He looked up and told me that he liked the series a lot and now wished he'd agreed to do the script when I first asked him to. That may be the best complement I've ever received on my comics work.

How did people react to the story when it first came out? I'm thinking specifically of how it treated dragons, which was probably different than most people thought about them.

As far as I know, until "Last of the Dragons" was published, most North American and European comics stories featuring dragons focused on European dragons. The Asian dragons featured in "Last of the Dragons" were pretty unique. I received a few comments about that. People seemed to enjoy looking at the legendary beasts from a very different perspective.

I didn't get to see any of the letters readers sent, so audience reaction was hard to gauge. At conventions, I received some nice reader feedback. Most of the reactions I got were from peers in the comics business. Their comments were very favorable, however, I don't know if anyone who didn't like the series would have come up and told me so! The best indication I got that "Last of the Dragons" was sincerely appreciated was when Archie Goodwin told me that, whenever the latest edition of "Epic Illustrated" was distributed around the Marvel offices, he'd walk around to see what stories people turned to first. When "Last of the Dragons" began being serialized in the magazine, he said most of the people he observed immediately focused on "Last of the Dragons."

"Last of the Dragons" is a small story, but there's so much going on in it. Was this always intended to be a one-off project, or did you have other ideas and plans for these characters and this world?

"Last of the Dragons" was originally conceived as a self-contained story. Since my time to work on it was limited (I was working full time as a storyboard artist), the page count was much lower than the story really needed. A lot got cut, or heavily condensed. For example, the priest Hokan goes from having a vision of Takashi to suddenly finding and hiring Takashi's ninja clan. Hokan's search for Takashi could have easily filled one or two chapters!

In recent times, I've fleshed out the original story (adding several new characters) and worked out what happens to Takashi, the last few dragons and their allies after the events of the graphic novel. I've been developing it in hopes of setting up a TV series. The TV series bible goes into great depth on a variety of topics not covered in the original comics, including the history of the ninja clan Takashi is adopted by, the history of the dragon priesthood and Shonin's experiences when he traveled to America before the events in the original "Last of the Dragons" story.

You were working as an artist and a writer on projects at the same time that you were editing. How did you balance all that?

Since my editorial duties were more than a full time job, I produced a fairly low volume of my own creative work during my 13 years on Marvel's editorial staff. I could only work on my writing and/or art projects at night and on weekends. When I got married and started a family, that situation affected my time as well.

I proposed "Punisher War Journal" to publish on a six week schedule. That allowed me to write and do layouts for the book while still working on the editorial staff. However, the book became a huge hit so rapidly that the company wanted it to go monthly as soon as possible. Jim Lee didn't need anyone doing layouts for him so I decided to write the title as a monthly. Jim did all of the pencils, and we brought Scott Williams on board to ink.

Much of the art I produced during that period was never seen outside of Marvel. These were roughs I drew when mentoring new art talent. I also did cover layouts (sometimes very rough!) for a lot of the titles I edited. On his blog, Kevin Nowlan has a few examples.

Are there any projects you edited that you're especially proud of working on?

That's almost like asking a parent who their favorite child is! I had the pleasure of working on many projects with lots of great talent. That said, "Alien Legion" holds a special place. "Power Pack" is a special title I'm proud to be associated with. Developing the Punisher from a second string guest star into a cross media franchise was fun.

When I took over as head of the Epic imprint, the first project I set up was the "Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser" miniseries by Howard Chaykin, Mike Mignola and Al Williamson. I'm still very proud of that one.

Much of my time at Marvel was spent discovering and mentoring a lot of talent. That was very satisfying.

Could you talk a little about what that involved and some of the people you worked with over the years. You've been teaching since then and I'm guessing you enjoy teaching.

When I was a fan trying to turn pro, it was frustrating to mail copies of my work to the publishers and either not get a response, or get one ages later that told me nothing useful.

When I was asked to join Marvel's editorial staff, I vowed that every submission sent directly to my office would get a quick response that would include useful information -- pointing out strengths and weaknesses, recommending specific instructional books to read and/or drawing exercises. It was a lot of work added on to the normal editorial work load but it was important for several reasons. First, whether or not the samples showed promise (the vast majority did not), they were being sent in by Marvel's most dedicated fans. These people not only loved reading Marvel Comics, they wanted to help make them. To let their submissions sit around collecting dust for extended lengths of time (and then possibly sending them a generic form letter) was inconsiderate to Marvel's most ardent fans. At the very least it was bad PR.

During my first day on the job, I discovered Art Adams' samples while going through the stacks of submissions I'd inherited from the office's previous editor. I showed the work to my assistant editor, Ann Nocenti. Eventually she teamed with Art to create the "Longshot" miniseries.

As word got around that submissions sent to my office got a quick response, the volume of submissions skyrocketed.

Eventually, I ended up with a loose baseball team model for developing talent. The major leaguers were working on the monthly titles I edited. The AAA talent worked on fill-in issues, miniseries, annual back ups, etc. The AA talent worked on a 6-page training story not meant for publication. The story was usually "Double Vision" written by Tom DeFalco. It was a tough story to draw and really put new talent to the test. An artist's strengths and weaknesses became quickly apparent when drawing that story. The artists would produce layouts. After I gave them feedback (often with tracing paper overlays showing corrections), they would produce tight finished pencils. I'd then give feedback for corrections to be made to the finished pencils. Sometime the finished Double Vision pencils were used to test the skills of new inkers.

When one of the major leaguers left a book -- often lured away by the X-men office! -- I had the option of calling up someone from the AAA "roster." Occasionally, a talent would jump quickly from the AA level to the major league level. Jim Lee is an example. This meant I didn't have to try and "raid" talent from another editorial office.

Even though the efforts were not always successful, I also tried to train new talent to be reliable professionals. Many fans who dreamed of creating comics had never held any type of job, much less a job that required them be reliably creative on demand.

Some very talented people could not produce the work reliably -- even when allowed to create their own schedule. Late artists who at least kept me posted on their trials and tribulations got a longer leash than those who just let their deadlines pass without a word.

The excuses some artists came up with for failing to live up to their deadline commitments were pretty funny, but ultimately sad since it meant that I'd have to cease dedicating time to help mentor them and move on to a new prospect that, hopefully, was more reliable.

I have to ask, after so many years of working at Marvel how did you end up writing "The DC Comics Guide to Creating Comics?"

I'd hoped to write a similar book while I was still at Marvel. In the evenings and on weekends, I'd written the curriculum for a new art training program that Marvel planned to begin. New talent would be trained in the office every day and also help do art corrections work for John Romita Sr. When the Ron Perelman regime at Marvel began self-destructing, plans for the art training program were scrapped. After that, there was little interest in my art training book idea at Marvel.

In 2001, I was consulting for Paul Levitz at DC and submitted the proposal for what became "The DC Comics Guide to Creating Comics: Inside the Art of Visual Storytelling." It was quickly approved, but the editor on the project left and the project was in limbo for many years. After jumping through a lot of hoops due to personnel and corporate structure changes, it finally got done and published in 2013.

What are you working on now?

Comics projects I'm working on include crafting a story for a new "Alien Legion" comics project. The most recent one, "Uncivil War" was collected in a hardcover by Titan Comics. I've also been very slowly working on two very large history-based comics projects. One is set during WWII and Bill Reinhold is producing the art.

These days I do freelance assignments for several marketing and education clients and teach at School of Visual Arts in NYC. I also teach online for San Francisco-based Academy of Art University. I've given my seminars on sequential visual storytelling to a wide range of education institutions and companies including Pixar, Blizzard Entertainment, Ogilvy, Psyop, SCAD, NYU, Society of Illustrators, Blue Sky Studios, SUNY Purchase, Roy H. Park School of Communications (at Ithaca College) and Syracuse University.

For some time, my "Alien Legion" screenplay has been in development at Bruckheimer Films. Still waiting to see whether or not it'll end up in front of the cameras!