Despite being such an important part of the comics industry, there can be a tendency to think of graphic novels as a separate, compartmentalized medium with no connection to our monthly, single-issue releases. There's a belief among some that readers tend only to be interested in one side or the other, with little or no crossover to be found between the two. This path of thinking can lead to an arbitrary disconnect, denying readers the chance to enjoy the best of both worlds.

In order to try and sort things out a little and give a better view of what graphic novels are and how they fit into the overall comics picture, CBR arranged a roundtable interview with three of the most acclaimed people in the graphic novel business.

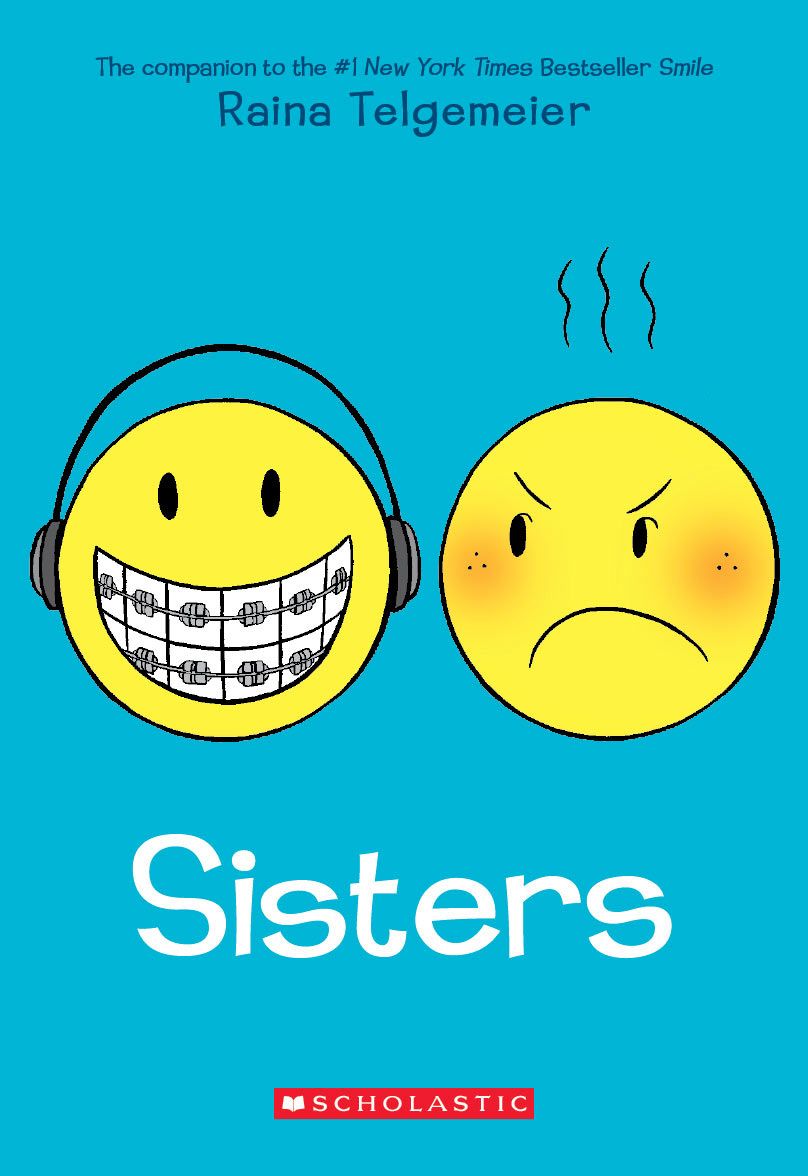

Raina Telgemeier is the creator of "Smile," which won an Eisner Award upon release and spent more than 50 weeks on the New York Times Best Seller list. The initial print run of her newest book "Sisters," a semi-sequel to "Smile," is for 200,000 copies.

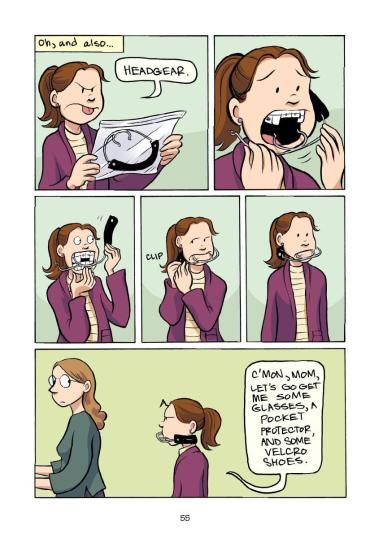

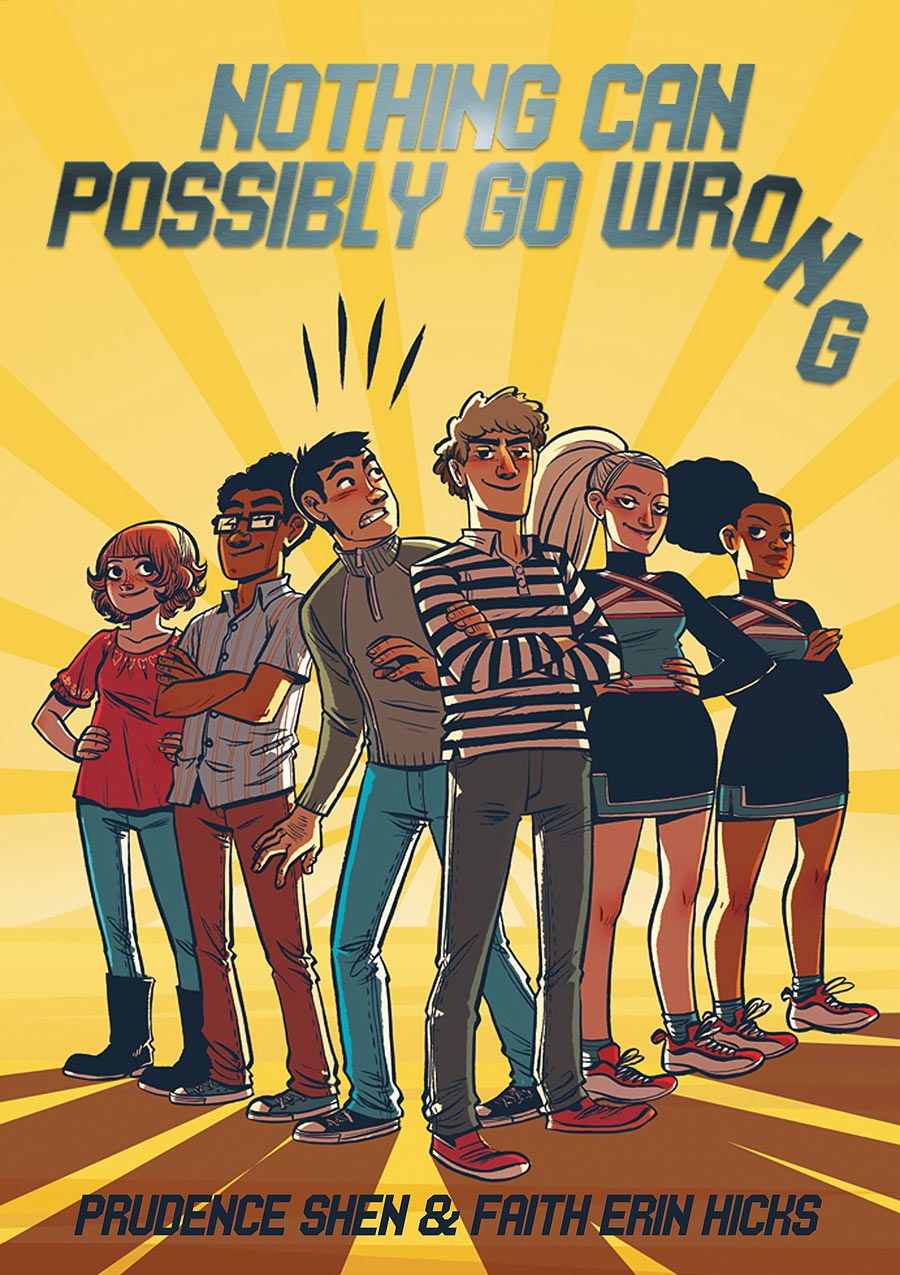

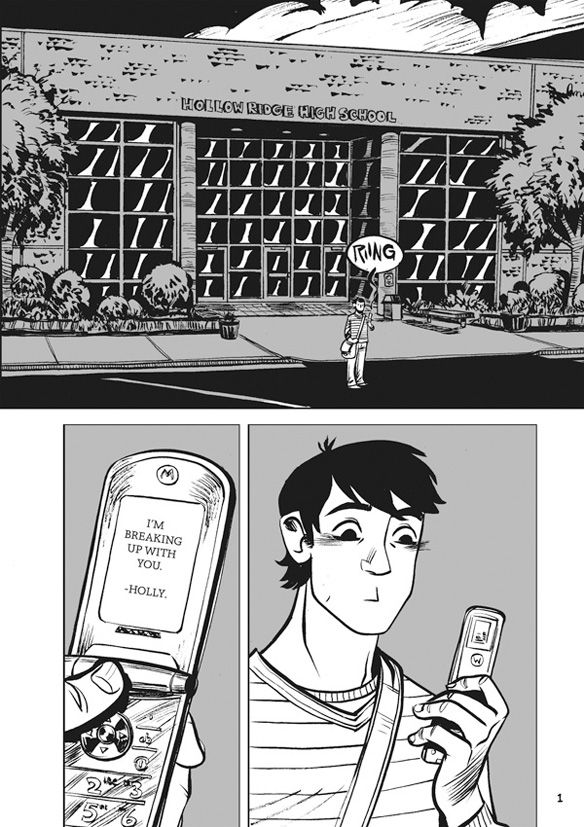

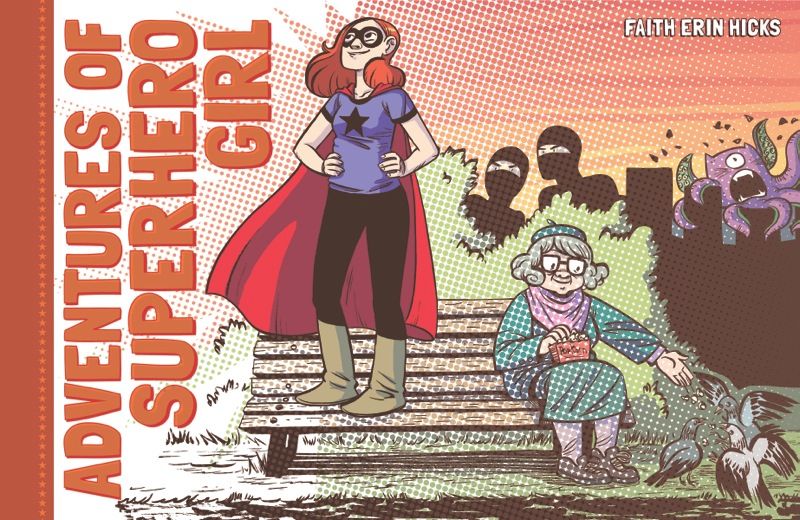

Faith Erin Hicks started out publishing webcomics, including her acclaimed series "Demonology 101." Since then, she's kept one foot in digital whilst embracing print; creating books like "Friends With Boys" and working on stories like "Bigfoot Boy" and "Nothing Can Possibly Go Wrong." Last month, she won the "Best Publication for Kids" Eisner Award for "The Adventures of Superhero Girl."

Calista Brill is the Senior Editor for multi-award-winning publisher First Second, which published -- among many others -- the aforementioned "Nothing Can Possibly Go Wrong." This years releases have included the acclaimed "This One Summer" by Mariko and Jillian Tamaki, and "The Shadow Hero," by Gene Luen Yang and Sonny Liew. She is a highly respected editor, with an undeniably strong track record.

Together, they have sold hundreds of thousands of books, to a massive range of people. They work at the top of their industry, and have an amazing insight into a world many comics readers may not have been exposed to.

CBR News: You've all been involved in graphic novels for years now, but what was it that first hooked you into graphic novels as a medium?

Faith Erin Hicks: I'm Canadian, so like most Canadian kids, I grew up reading "Tintin" and "Asterix" comics. I remember always being very attracted to comics; something about the combination of pictures and words forming a narrative is very appealing to me. I didn't read very many comics through my teens, although I did read a few X-Men comics.

Availability was an issue: I grew up in a small town that did not have a friendly local comic store, and comics were not yet supported by libraries. So although I wanted to read comics, I didn't have access to many. When I was in my early 20s, I discovered "Bone" by Jeff Smith, and that became a touchstone for me. It was a comic that I felt was written and drawn with a reader like me in mind.

It was also a comic written and drawn from start to finish by a single person, which was very different from the X-Men comics I was reading at the time. Since "Bone," I've discovered how diverse comics are, and now read a wide variety. Last year I kept track of how many graphic novels (I include TPBs in that) I read, and it was over 100. Most of them were pretty good, too!

Calista Brill: I also grew up reading comics. Early favorites were "Uncle Scrooge" and "Little Lulu." I fell deeply in love with "Elfquest" as well, and also discovered "Love & Rockets" and Jim Woodring's "Frank" pretty young. It's a little hard to articulate what the appeal is, though it's a powerful one -- I guess I just love stories, and I love looking at pictures, and comics give you both of those things, so I was sort of helpless to resist from day one.

Raina Telgemeier: I came to the medium via newspaper comic strips, and started buying the collected volumes of my favorites: "Calvin and Hobbes," "For Better or For Worse," "FoxTrot." Then, my dad passed me his copy of "Barefoot Gen" the summer of my tenth birthday. I had always liked reading longer books, so being able to get lost in a comic for hours (rather than the minute or so a single strip took to read) really appealed to me.

Aside from "Barefoot Gen," I didn't read any other graphic novels until I was 15 or 16 -- and then it was "Maus," followed by "Bone" when I was in college -- same as Faith, "Bone" became a huge touchstone, and was the final, inspirational kick in the butt for me to want to tell long-form stories.

What is it about now, making and publishing full, book-sized stories which appeals to you?

Hicks: As a reader, I tend like stories with a beginning, middle and end, so those are the kind of stories I want to make myself. I've enjoyed some long form manga (I'm a big fan of Naoki Urasawa and Hiromu Arakawa), but I haven't really followed a comic that didn't have a definite ending that was coming at some point.

Like everyone on the planet, I'm reading and enjoying "Saga," so it'll be interesting to see how many years and trades it'll go before I start getting eager for it to end -- although that may be the one magic comic that I'll never get sick of, who knows?

As for my own stories, I like collaboration, but I also like that in comics I can do pretty much everything on my own -- except for publishing. (Please continue to publish me, publishers!) I love being able to create a story from start to finish all by myself.

Brill: What Faith said! As an editor, I love working on projects where I can put some real thought into shaping the work as a whole -- into making it graceful and satisfying and intentional from start to finish. It's kind of exhilarating to watch people like Faith and Raina sit down and create something on the scale of a graphic novel. I have a front-seat row to the coolest -- and hardest -- job around.

Telgemeier: Just echoing these two! I've always loved sitting down and reading a good, thick book with a beginning, middle, and end -- whether that book takes an hour to read, or a week. I like the quick satisfaction of making short-form comics too, but spending a couple of years to craft a solid story is infinitely more satisfying, as is knowing I'm giving the reader a complete reading experience.

I also just love the tactile experience of flipping through a thick brick of printed paper; the smell of a new book is up there with bread warm from the oven.

How do you decide what stories you want to tell? Do you ever have an idea and then think "Wait, this won't work as a long-form story" and have to try something else?

Hicks: At this point, since I write and draw comics for a living, I tend to want to do stories I think my publishers will want to publish. So all my super nutty ideas go in a folder for "someday in the future." I try and think of short stories, but for some reason, most of my ideas tend to expand and become long-form, eventually. I guess I just have the tendency to ramble on, which is kind of terrible.

Occasionally I get invited to be a part of anthologies, so that's a good excuse to try and do a short, contained story, but I find those really hard. I like stories where I have lots of time to expand the world and characters I'm writing.

Telgemeier: My ideas tend to come in flashes from out of nowhere, and sometimes those ideas make me lose sleep for hours and days and weeks, as I process them in my mind before I set paper to pencil. The ideas (and characters) that just won't let go of my brain tend to be ones that have legs.

I'm not a terribly long-winded person, but I do like my books to have tons of breathing room. That means a story might not take all that long to tell, but pacing out the narrative in a way I find satisfying might take several hundred pages. If it means a reader burns through my book in 30 minutes, that's okay -- graphic novels merit re-reading, to fully appreciate the art, the jokes, and the rhythms.

As for how to decide which stories to tell, my new book "Sisters" is an example of a book I didn't realize was going to exist until I wrote it. "Smile," which is autobiographical, proved to be really popular with young readers, most of whom wanted to know when the sequel was coming out. Well, I didn't think it was possible to write a "Smile" sequel!

That story is about a very self-contained time in my life, dealing with a specific problem (my dental drama), which came to a resolute end when I was 15. The next phase of my life had nothing to do with teeth or dentistry. And, there was no other experience from my childhood that I imagined would fit into a nice, neat, self-contained package.

But the more I thought it over, the more I realized there were indeed lots of anecdotes and funny stories from my childhood, and cherry-picking the ones that added up to a narrative came more easily than I thought it would. "Sisters" is being marketed as a "companion" to "Smile," because it's the same characters and told in a very similar format, but the story is completely stand-alone. You can read either book before the other.

To pick up on Faith's thoughts about anthology work: I enjoy the challenge and constraints of doing short-form comics, but I've found that I do my best work when I have few distractions. Producing multiple stories at the same time is getting harder for me as time goes by, and the more I travel to promote my books, the less time I have for side projects. I've turned down a lot of really fun-sounding short projects this year, in the interest of keeping myself focused and on track.

Brill: I look at a lot of pitches, and have to decide which ones seem like they'd make sense for First Second to sign up and publish. One of the things I try to figure out about each pitch is, "Is this enough/too much story for a graphic novel"? Sometimes, even when the answer is no, I still try to find a way to make it work. We publish books that range in length from 48 to 600 pages, so --

Is there a feeling ever that you have to stay within a certain genre to attract attention, or do you find you can freely experiment in style, storytelling and narrative? How does the medium treat genre?

Hicks: I've been lucky in that so far, I've been able to write and draw the stories I want to make. I've occasionally worked with writers on other projects (I did a kids book series called "Bigfoot Boy" with J. Torres, as well as a prequel to the video game "The Last of Us'), but for the most part, I've just had ideas that I like and my publishers have been okay with publishing those stories.

I like working within the supernatural/young adult genre, probably because "Buffy the Vampire Slayer" had such a huge impact on me as a teenager, but I like a lot of genres. I like science fiction, I like zombies, I even occasionally like realistic fiction. Sometime publishers seem to want you to stay within a genre where you've previously been successful (which is understandable), but I've been lucky with my publishers mostly supporting the different directions I want to go in.

Sometimes I feel kind of not nerdy enough for comics, but too nerdy for the book trade. When I look at what's really successful in the direct market, it seems to be a lot of genre-heavy stuff. And I like a lot of those comics. I love stuff like "BPRD," all these superhuman and human characters dealing with the end of the world and humanity. Totally love that stuff.

But I also really enjoy books like "Fun Home" or "Tamara Drewe," which are very grounded in realism. A lot of people in the book world know me for "Friends With Boys," which on the surface seems kind of realistic, but I think is actually a very nerdy book, even if it is about a teenage girl and her friends.

So sometimes, I feel like I maybe have to cover up my nerdy tendencies to be successful in the book market, but then, maybe I lose the comic market because I'm not writing and drawing something genre-heavy? I don't know. I'm probably over-thinking.

Telgemeier: I don't know about attracting attention, but my publisher is really happy with what I'm currently making: Realistic comics for a middle grade audience, starring middle-school-aged girls. I was a 9-year-old girl who loved comics, so it made sense to write books for girls like I was, even though at the time my first book was published (2006) there wasn't a lot of evidence that the audience was there. But they absolutely are, and I'm thrilled I get to make comics for them to read!

When I wrote "Drama," it was originally going to be about high school kids, but my editors talked me into aging them down to middle school. In that sense, at the time, I felt like I was being told by a marketing machine that my audience was very young, and it was going to stay young, and it would be wise to keep making books to satisfy that appetite.

I struggled with that idea, until "Drama" was actually published; then I discovered Scholastic was absolutely correct. There will never be a shortage of 9-year-old readers in the world, it turns out.

The book I'm cooking up now has just a little bit of a genre bent, which is new for me, but it's still grounded in realism. At some point, I might like to try something completely different, but I'm comfortable and happy doing what I'm doing. I'll cross the next bridge when I come to it, I guess.

Brill: First Second as a rule doesn't publish a lot of "genre" stuff (sci fi, fantasy, crime, superhero, etc). But every time I say that, I think of a different exception on our list. I guess maybe it'd be more accurate to say we don't only publish "genre" books. We try to publish as wide a variety of different kinds of books as we can, and some of those books seem to generally do better in the market than others. It's something we pay a lot of attention to but try not to let ourselves be completely ruled by.

Is there a standard demographic for your readership? For that matter, is there a set audience within the world of graphic novels, do you think?

Telgemeier: Well, I just spent several paragraphs extolling the virtues of 9-year-old girls! Who are awesome, and make up the bulk of my readership, at least as far as who writes to me and comes to my events. But they're not the whole picture. I have older brothers, dads, 40-year-old librarians, theater majors, moms-who-are-New-Kids-On-The-Block superfans, grandmas, 5-year-olds, and everyone in between as readers.

I don't think graphic novels have a set audience, because graphic novels themselves aren't a genre -- so you can have all kinds of graphic novels for all kinds of readers. All that determines their audiences is their availability, so now that you can find book-length comics in libraries, elementary schools, big-box retail stores, college literature courses and online, almost everyone has access to them.

Hicks: From what I've seen, online and off, I'd like to believe my readership is a healthy mix. I think my books like "Friends with Boys" or "Superhero Girl" age up or down pretty well. So I have teen readers and younger, but I also meet adult readers who say they like my books. It's pretty nice, actually. I've seen a very broad spectrum of readers, which is very encouraging.

I kind of joke about wanting to be Jeff Smith when I grow up, but he literally made a comic that I would give to a 9 year old or a 90 year old, and that's something I really strive for in my work. I don't really know about the gender divide of my readers. I know a lot of women read my comics, but I've met a lot of dudes who do too.

Brill: "First Second publishes great graphic novels for every reader" is our unlovely but hopefully accurate motto. Not all of those readers know they want to be reading graphic novels yet, is the thing. Our job is to find them and convert them.

Is this even something you consciously choose to do, or are you just naturally more inclined to tell all-ages-appropriate stories, do you feel?

Hicks: In terms of the stories I want to tell right now, I'm very attracted to all ages stories at the moment. Three of my current favorites are "Avatar: The Last Airbender," "Fullmetal Alchemist" and "Bone." I think all of these stories are appealing to a wide readership, and exemplify the best kind of storytelling for all-ages (although probably not wee little ones).

They all have dark, dramatic elements to them that anchor the story, but they're also very good at comedy and not allowing the darkness to overwhelm the story.

At this point in my career, I'm not very interested in grimdark storytelling. I'm bored by movies or comics that are so completely dark, it's like the storyteller is trying to grind it into your brain. It's an exhausting reading/watching experience, and I don't think it's necessarily "mature" storytelling.

Telgemeier: I'm an overachiever and a people-pleaser, so I've always liked making things that can appeal to everyone. People often apply the term "all-ages" to Pixar movies, and while Pixar didn't start making movies until I was a teenager, I did grow up as a huge Disney Kid -- and my dad was a total Disney Dad. It's fun being able to create things that span generations.

I also just have a kid-like sensibility, I think; call it arrested development, but I still powerfully relate to and empathize with kids. I never wanted to grow up. I was mad when I got boobs. I was upset when my friends started drinking as teenagers. If I could live in a perpetual 10-year-old time capsule, I would, and writing books about being that age seems like the best solution.

A comics publisher would absolutely market my work as all-ages, but because I work with a trade book publisher, they have to be more specific. Thus, my work for Scholastic is deemed "middle grade" (roughly, for ages 8-12) and I sometimes have to convince people that it's still okay for 5-year-olds and their grandmothers to read my work, too.

Brill: As someone who works in the publishing industry I spend a lot of time thinking about categories and age ranges and how to communicate those concepts both to creators and retailers. I try not to shoe-horn the authors and artists I work with into awkward-fitting categories, but I also advise them on what audience they can best reach, and what the market expectations are going to be as far as content goes. I keep a light touch here but it's definitely part of my job.

For example, Faith's trilogy that she's developing with us definitely counts as all-ages, but that term isn't very useful in the world of publishing. Everything is category-driven. So I'm quietly toiling behind the scenes to figure out which category we want to present Faith's new series as, even though from her point of view -- and, ironically, from the point of view of her eventual readers -- it's all-ages.

In my experience, the categories tend to matter a lot to the middlemen and not so much to the creators and consumers of graphic novels.

I believe you've said before, Calista, that First Second have three divisions: kids, YA and adult fiction. How important to you all is it that you target your books not just for older readers, but also for new readers, and young readers?

Brill: Super important! We love publishing for as wide a variety of age ranges as possible. Lately, we've been trying to get some really young projects out there, which is new for us, and it's been great fun. Basically, we aim to have at least one book you can hand to anyone and they will love it. And that includes 3-year-olds.

Despite the huge appeal of graphic novels -- your new book "Sisters," Raina, has been announced as having an initial print order of 200,000, which is absolutely massive -- I know that you've all spoken before about the difficulty to get the comics community to talk about your work. Do you find it a struggle to get interviews with websites, or to have them host previews or cover publishing news?

Hicks: I'm just working on what I observe online, but I find it a little odd that more isn't being said about the importance of Raina's comics. There's an entire generation of kids growing up on "Bone" and "Smile," and that's just so amazing to me. And of course not all of those kids will continue to read comics, but some will.

If even a fraction of Raina's readers move on to my comics, or "Hellboy" or "20th Century Boys," that's still a huge amount of readers. And I just find it weird this is something that isn't really brought up much. I don't know if it's because "Smile" is technically a comic for kids, so the typical adult comic book reader is ignoring it or something, but I think it's a pretty significant omission by the comics community.

I dunno, I've been yelling about it a bit on Twitter. I'm not part of the comics blog-o-sphere, but I yelling about it on Twitter makes me feel like I'm contributing to some kind of discussion, I guess.

When it comes to my work, I feel like sometimes the comics media is interested, sometimes they're not. At this point, people like Heidi McDonald and Tom Spurgeon seem to know I exist, which is cool, so I'm pretty happy. Honestly, I would much rather yell about people not paying attention to Raina's work than not paying attention to mine. I don't have that much self-confidence.

But just the other day I saw a comic pro saying on Twitter, "If only anything in comics sold 100,000" and I thought, um, there is Raina right there. Are you not aware of what she's doing?

Brill: Right? It's weird, because we do get a lot of recognition and visibility in the comics community, but we also get a lot of recognition and visibility in the book world, and what's odd about it is how little overlap there is between the two. I think that's changing a bit, but slowly.

Telgemeier: My books didn't get huge print runs out the gate, I just want to point that out. I'm entering my tenth year as a professional graphic novelist, and my eighth as a published one. My first published work was illustrating the "Baby-Sitters Club" graphic novels, and that was after self-publishing my own minicomics and drawing webcomics for about 7 or 8 years. My self-published work enjoyed a little bit of press from indie comics sites like Sequential Tart and Optical Sloth, and I got nominated for an Eisner Award and an Ignatz Award pretty early in my career, which was wonderful!

I'm honestly not sure how people define the "comics community," and anyway, I've never made comics for a "mainstream" audience, if Marvel and DC are what people mean when they use that term. I've done a little bit of work for both of those publishers, but never on a monthly title and always in the context of "indie artists doing their take on things!"

So, I've never expected the fanboy community to have a huge awareness of, or interest in, what I'm doing. However, many fanboys eventually have young daughters. I've had countless mid-30s, male comic book fans discover my work because their kids got into it, and it manages to bridge the interest gaps in their families. And many of these people come to me for recommendations on what to buy their daughters to read next, and that's where I'm delighted to have Faith's books to suggest! Please keep making comics, Faith!

Is there ever a feeling that you are in competition for attention with single-issue comics, at all?

Hicks: I'm not really sure. It's not really something I've ever thought of -- sorry!

Brill: Me neither! But now I can tell this is going to keep me up at night, thanks a lot. *shakes fist*

Telgemeier: Again, it depends on whose attention you're competing for. Much as we all know and love comics, there is a world beyond the comics community. Libraries, for example, aren't able to shelve a single-issue, because it doesn't have a spine. Thousands and thousands of libraries stock graphic novels, though!

And graphic novels might not get as much shelf space in comic book shops, but they're being displayed on endcaps in Barnes and Nobles all over America. Different strokes for different folks -- why's everything gotta be a competition?!

Do you think that ignoring the place of graphic novels as a part of comics serves to downplay the importance of younger readers, of female creators, of self-contained storytelling?

Hicks: I'd say definitely the importance of younger readers and especially serves to ignore female creators, as there seems to be more women working within the book trade end of comics than the direct market. I guess I get pretty sick of articles that ask the question, "Where are the women creators in comics?" yet only look at superhero comics, with maybe a peek at what Image is doing.

There's a big, wide world out there, and when you actually look at all of comics, from graphic novels to self-published work to webcomics, the number of female creators rises quite a bit. I think counting out kids' comics is very problematic. As so many literary studies have shown, if you get kids reading at a young age, they are much more likely to continue reading as adults. And isn't that what we want for the comics industry? More people reading comics, so more creators can make living wages and continue making fantastic comics? I know I do.

Brill: Hear, hear! Though probably you could say the opposite as well -- that folks who are paying a lot of attention to graphic novel publishing aren't really keeping serial comics publishing in mind. I know I'm pretty ignorant about a lot of aspects of that world. There just aren't enough hours in the day, you know? It's two very different publishing models, and the readerships and cultures of them overlap but aren't identical at all.

Telgemeier: I don't have a lot to add that Faith and Calista haven't already said here. I have noticed that there are a lot of sites and blogs popping up that are all about the women in and of comics, and those sites tend to cover both sides of the spectrum: comics media and trade book media.

In general, I've always felt overwhelmingly supported and appreciated by the women in every aspect of the industry. Maybe that makes me a glass-half-full type, but I've been too busy being happy with what we have than being upset about what we don't.

The role of the Internet has been an interesting one for publishers over the last few years. Digital serialization has now become a fairly standard policy for First Second as a whole -- I believe you serialize one story a year, roughly, amongst them "Friends with Boys." What prompted you to try putting out a comic in this fashion?

Hicks: We web-serialized "Friends With Boys," as well as my most recent First Second graphic novel, "Nothing Can Possibly Go Wrong." I wanted to put them online, basically, and First Second was kind enough to be supportive of that. I got my start in webcomics, and wrote and drew them for years. I wanted to try going back to web serialization because I feel like comics still have an access problem.

Getting comics into libraries and onto iPads has helped draw in new readers, but it's still sometimes hard to get people to read comics. Not everyone has access to a good library, or comic shop. But pretty much everyone has the Internet, and access to a computer. I felt web serialization was a great way to give readers access to my graphic novels, and hopefully enough of them would enjoy the free comic that they'd want to pick up a hard copy of it.

Not everyone who read the comic online for free bought a copy of "Friends with Boys," but I believe enough people did that it was worth my time.

Brill: We decided to start serializing stuff online because we were pretty sure it wouldn't hurt sales and pretty sure it would probably help them. Which generally seems to turn out to be the case.

What have the results been, overall? Do you think digital serialization has formed a bridge, or sorts, between the reading experiences of single-issue comics and graphic novels? Given how many people predicted digital would be the death of print, that would prove to be an interesting turnaround, if so.

Hicks: I certainly think it's a great way to keep your comics in the minds of readers. It's a great way to engage with readers, and hopefully engage with them in a way that makes them attached to you. I hoped that by blogging online while both "Friends with Boys" and "NCPGW" were ongoing I could show people that there was a person who made this comic, and hopefully readers would find that person's work worth supporting.

Brill: What we've found is that it's an incredibly powerful way to build a readership for a print book -- and for a creator -- but that it takes a lot of work to do that! You can't just put a story up online and expect people to spontaneously create a community around it -- webcomics require a certain amount of personal presence as well.

So it's something we think about carefully with authors when we're considering putting something up online: do you have the time/energy to be present, interacting with your fans, on a daily basis?

Telgemeier: Can I just jump in, too, and say that having a web presence really helped me when it was time to publish my first books. Even having an audience of a couple hundred online readers meant I had people going to the store on my book's debut day, asking to order a copy, or buying one for a friend. Nothing is better for word-of-mouth than something people are already familiar with.

How do you feel about the medium as a whole, currently? Do you think that things are starting to strengthen? The importance of graphic novels is starting to get highlighted by critics, readers, the wider comics community as a whole.

Hicks: I see an incredible diversity of work being produced by the comics industry, from webcomics, to pamphlets to graphic novels and manga. There's a lot of great comics out there, so many that I can't keep track of them all (although I try).

It's really exciting to see how much things have changed even in the past 15 years; the kind of comics I really wanted to read when I was a comics-hungry teen are out there, and that blows my mind! I feel like comics have a real chance to -- I don't know, if not become a part of the mainstream, at least become an art form that is acceptable to all kinds of readers.

I love that I sometimes see kids reading "My Little Pony" comics at my local coffee shop, or a dude on a bus reading "Fullmetal Alchemist." More readers means more money coming into our industry, which means more comics sold, which means maybe more creators can make a living doing this incredible art form. At the end of the day, that's all I want. More comics!

Telgemeier: Graphic novels are enjoying a nice moment in the sun, for sure, and there's plenty of room for growth. I was just at the American Library Association's Annual Conference, and graphic novels and prose novels were getting equal treatment from publishers and readers alike.

I do sometimes worry that the bubble might burst. The key is good work. If too much so-so work gets published, there will be a glut. If what's published is really good, readers will continue to support it, and publishers will continue to support creators.

Brill: The only reason I think it's inaccurate to say that this is the golden age of graphic novels is that implies it isn't going to keep getting better and better -- and it is.