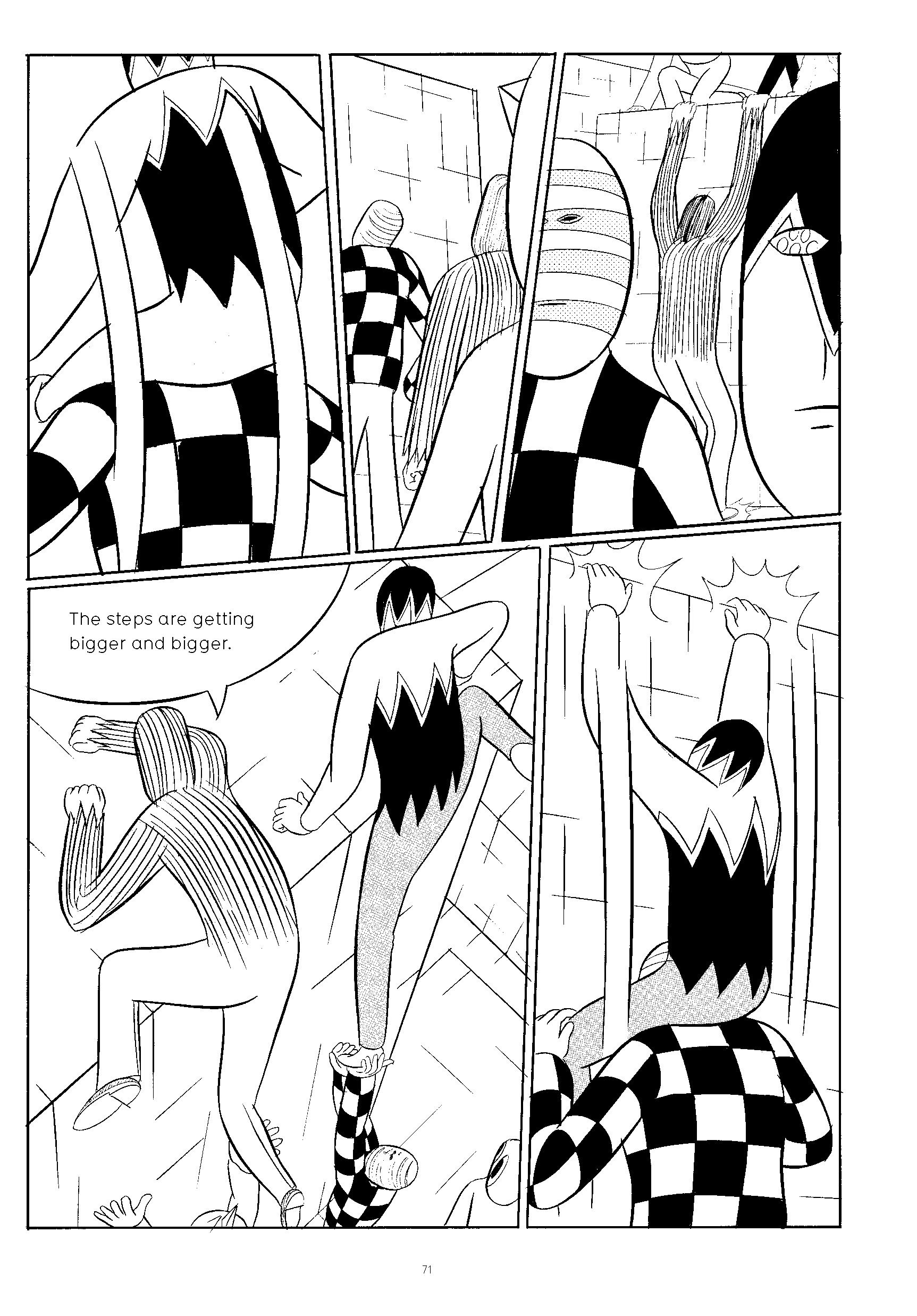

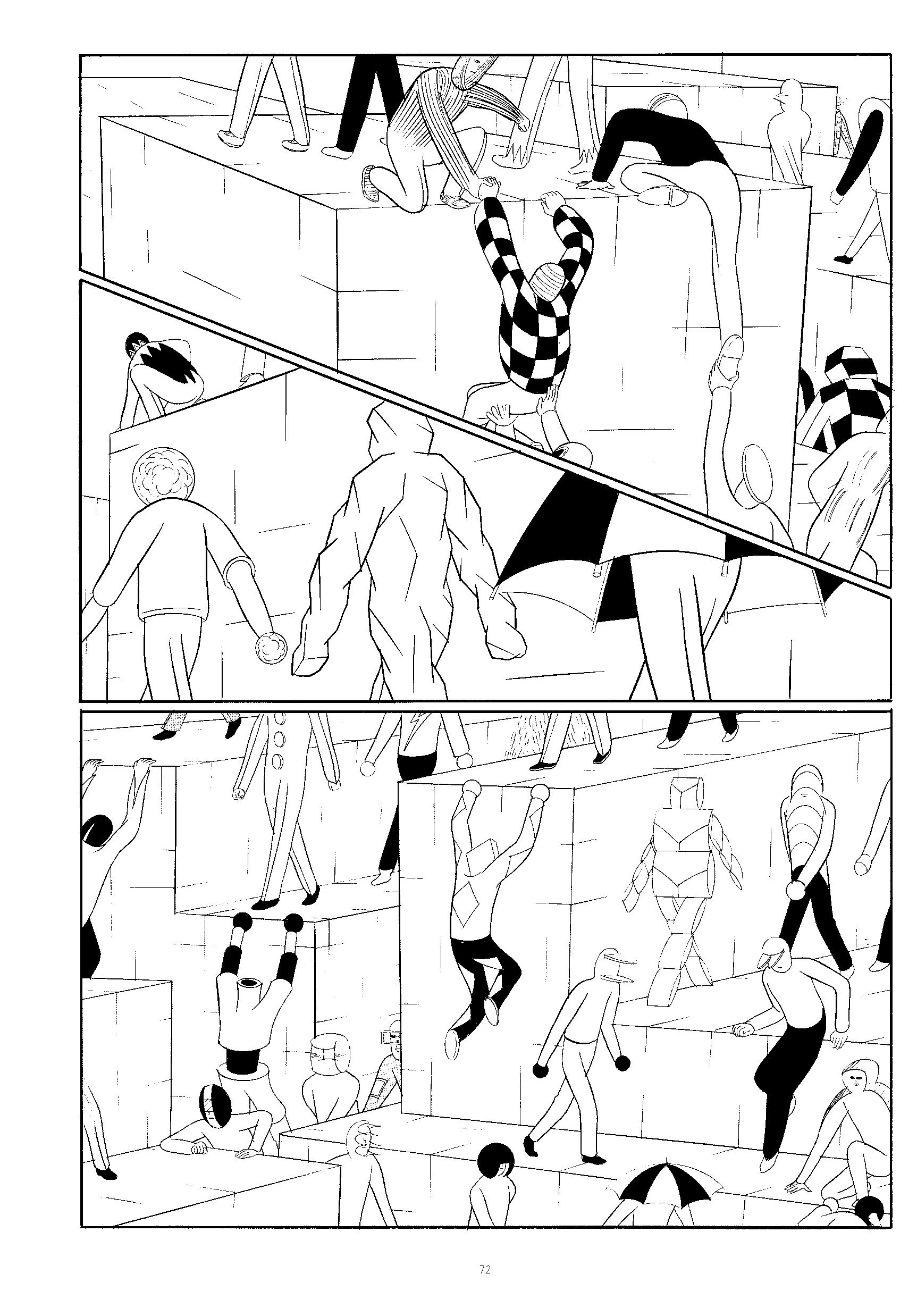

It's always a good sign, and a rare blessing, when you close a comic and say to yourself, "Well, I've certainly never seen anything like that before." Such was my reaction to Garden, the upcoming PictureBox graphic novel from acclaimed manga artist Yuichi Yokoyama (currently in Previews for a May 4 release; Diamond code MAR111221). Sure, this is the same guy who made guys throwing books at one another as exciting a fight scene as anything out of Kill Bill in his collection New Engineering. It's the same guy who made a bunch of dudes taking a ride on the train as thrilling as Jack Kirby drawing someone hijacking the Moebius Chair and going on a joyride through Apokalips in his book Travel. But Garden takes Yokoyama's unique combination of deadpan characters, robotically clean lines, zany costumes, epic sets and scenery, and hyper-caffeinated action to a whole new level. It's like a magical mental amusement park.

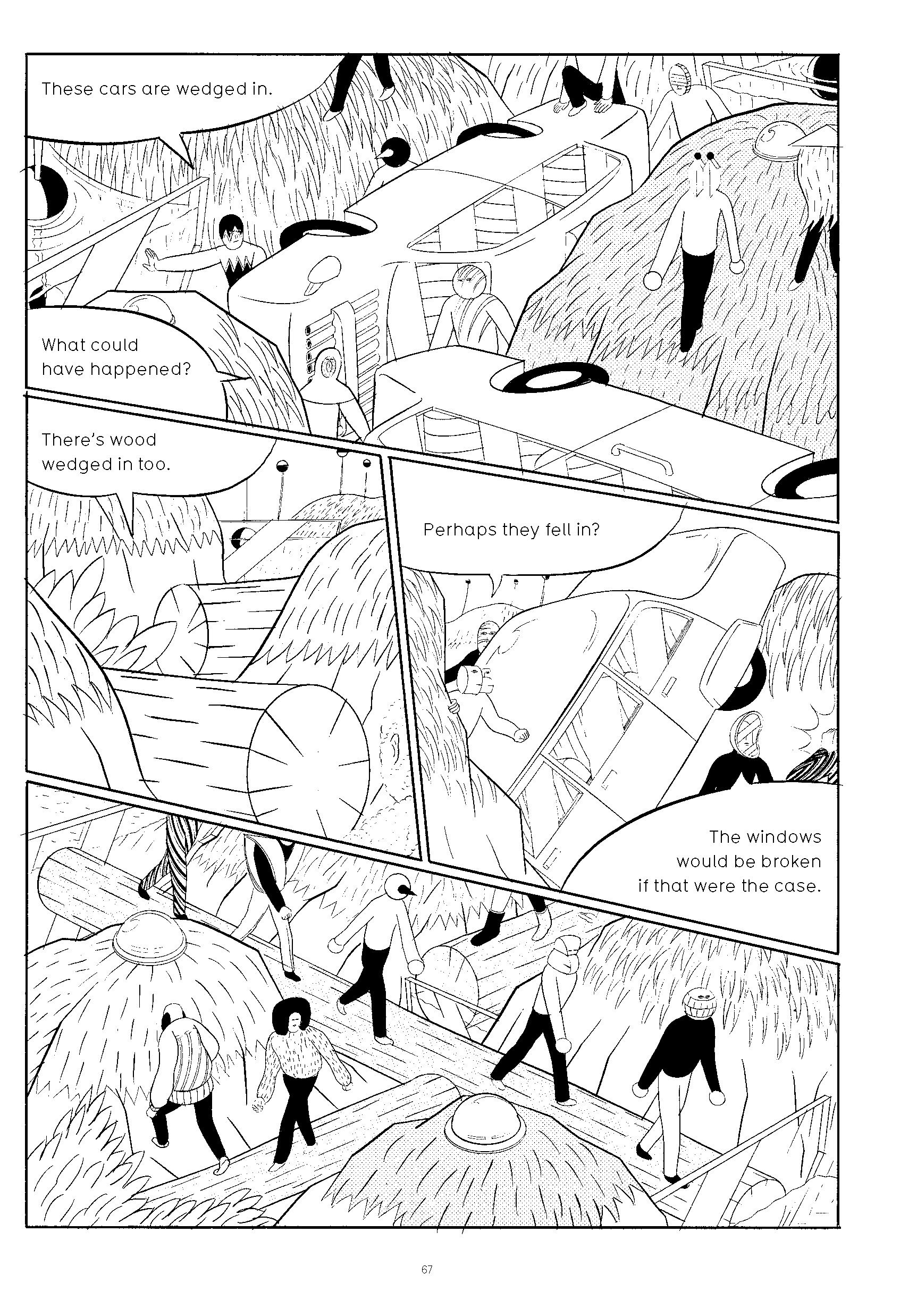

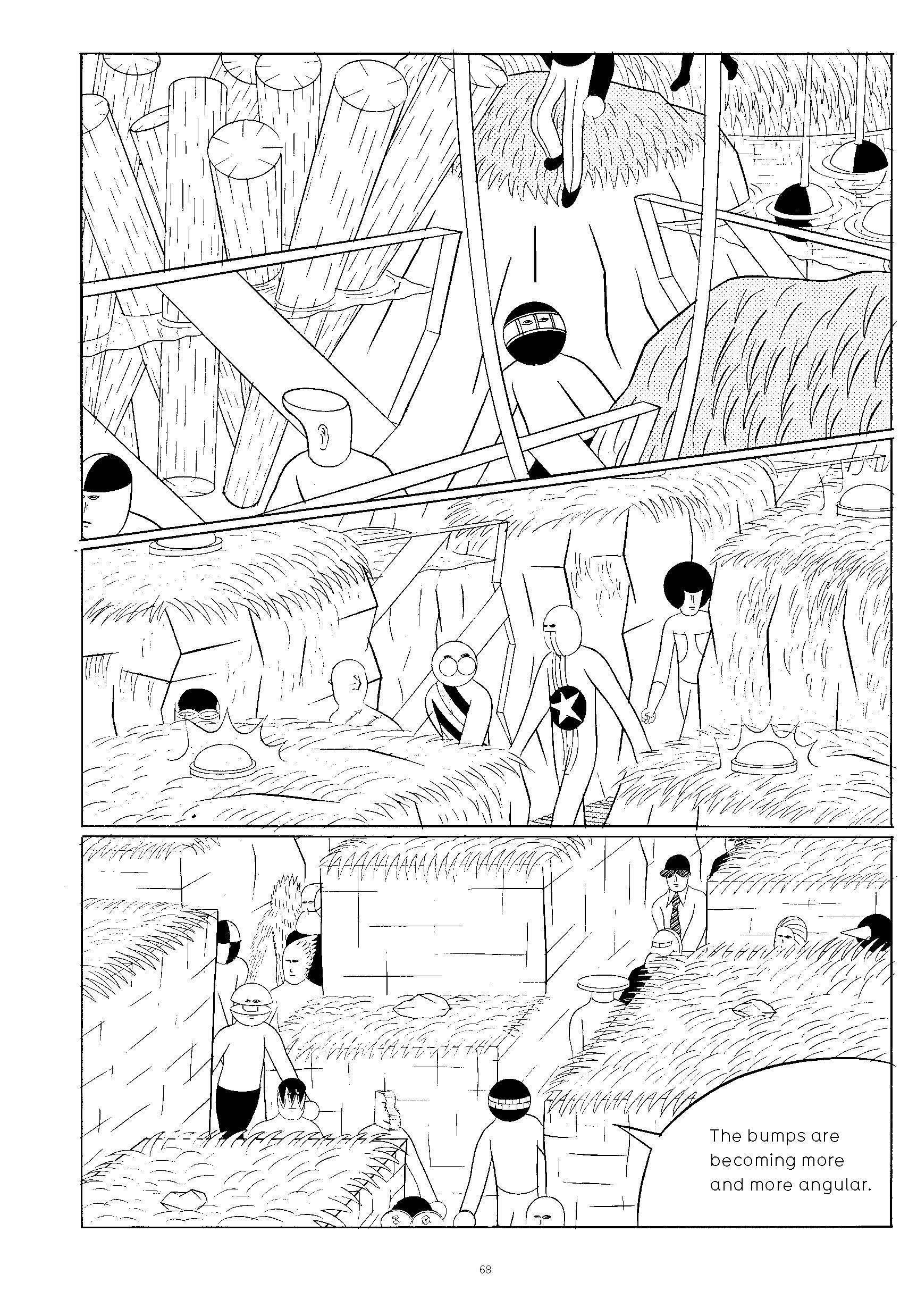

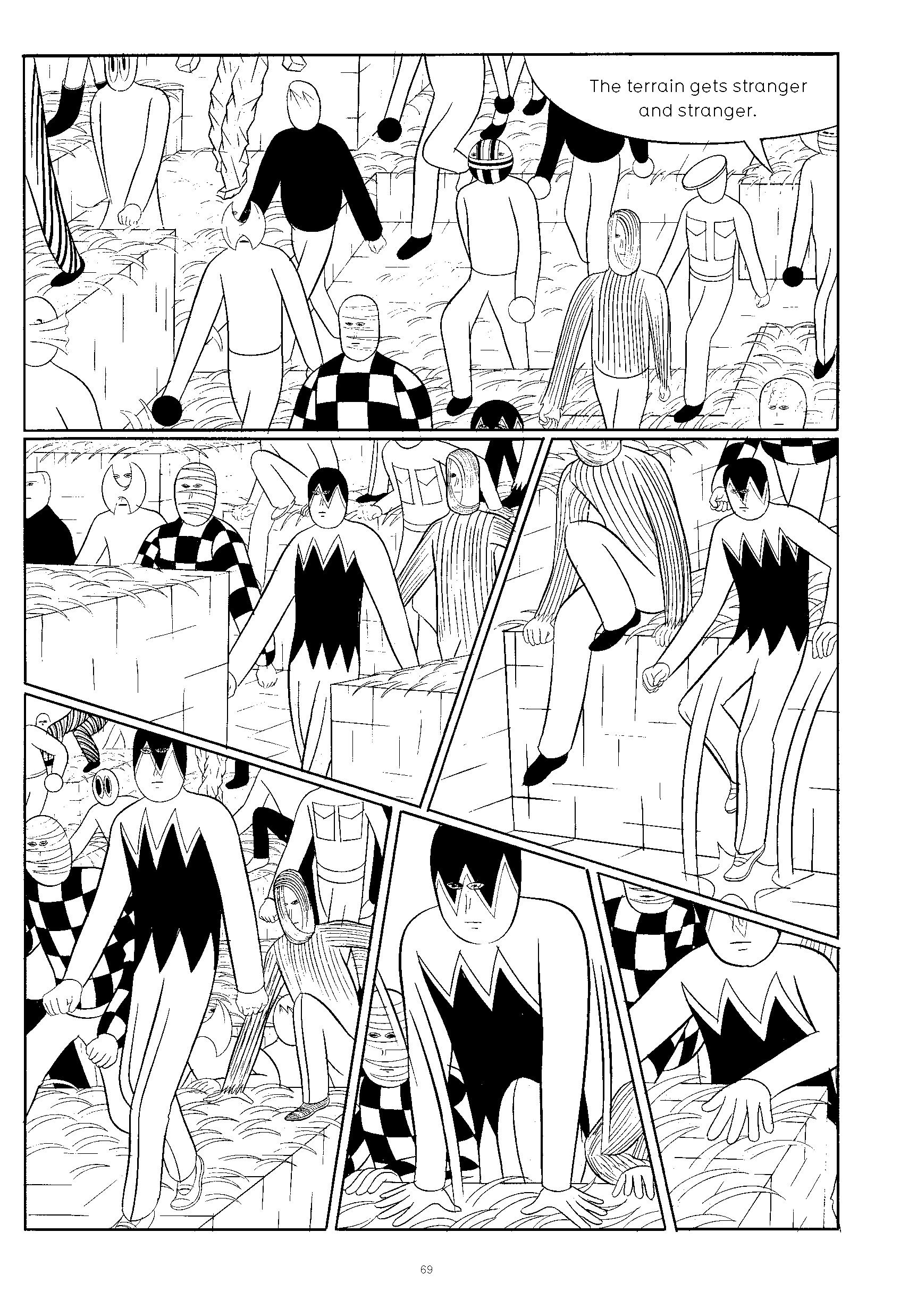

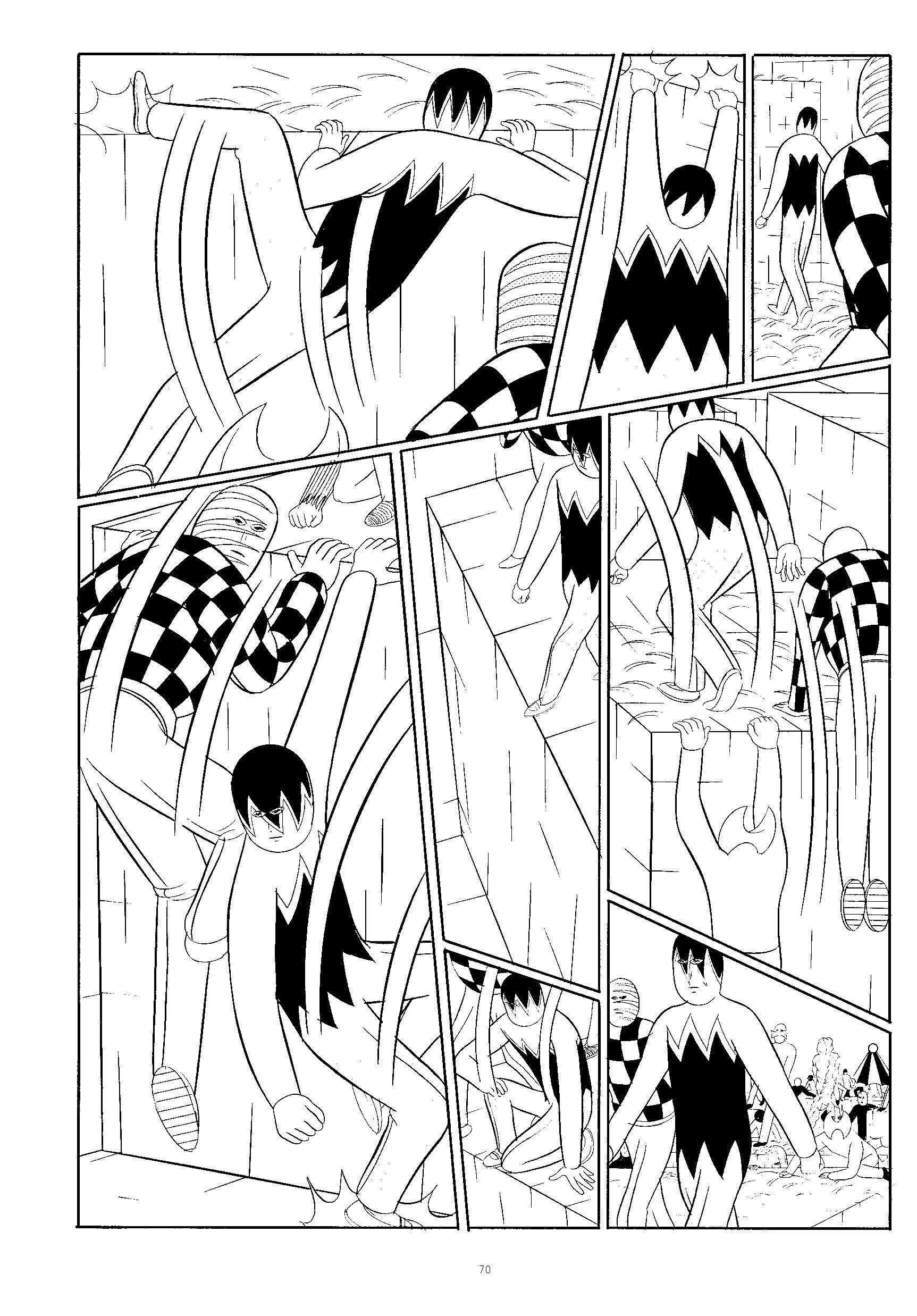

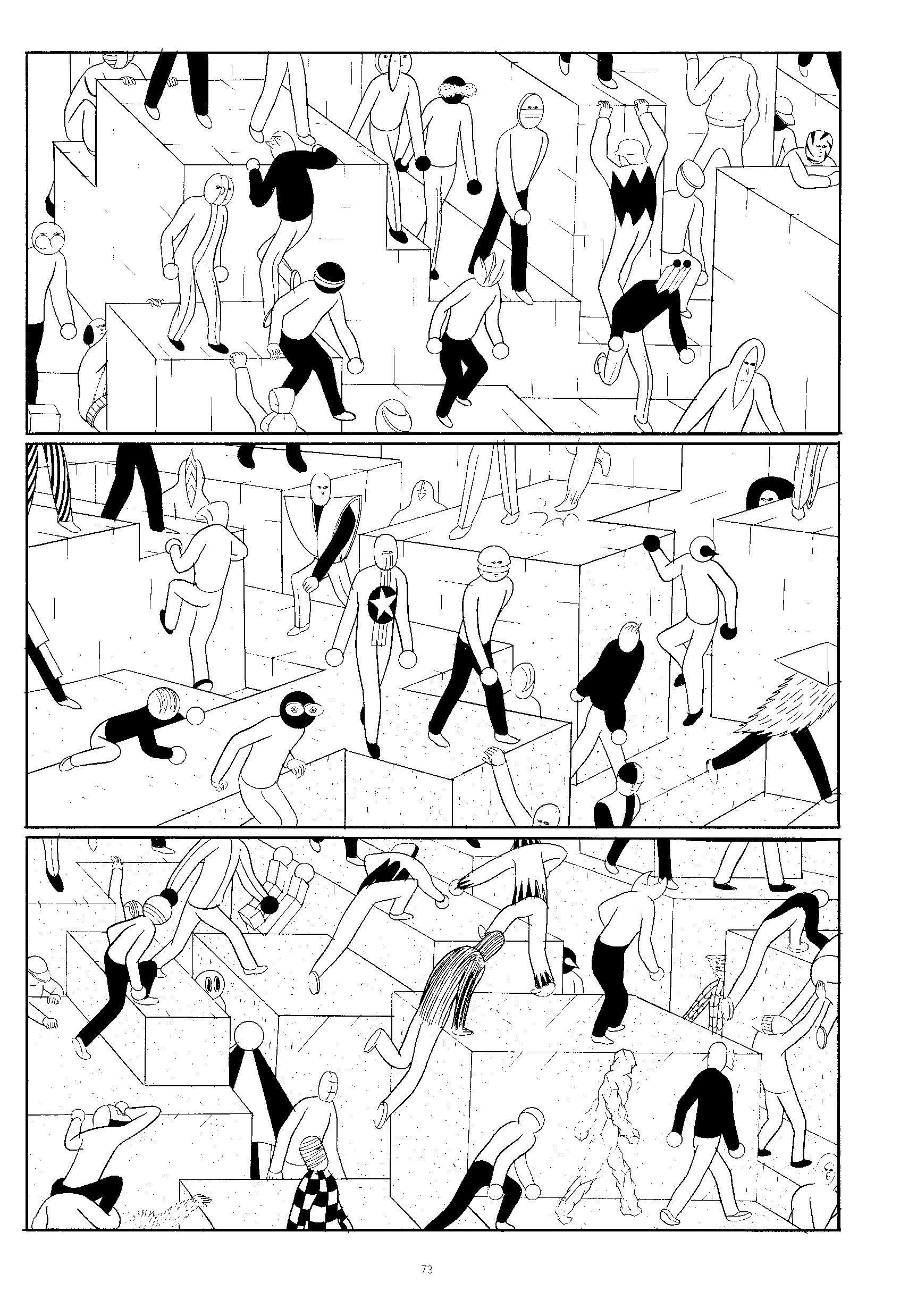

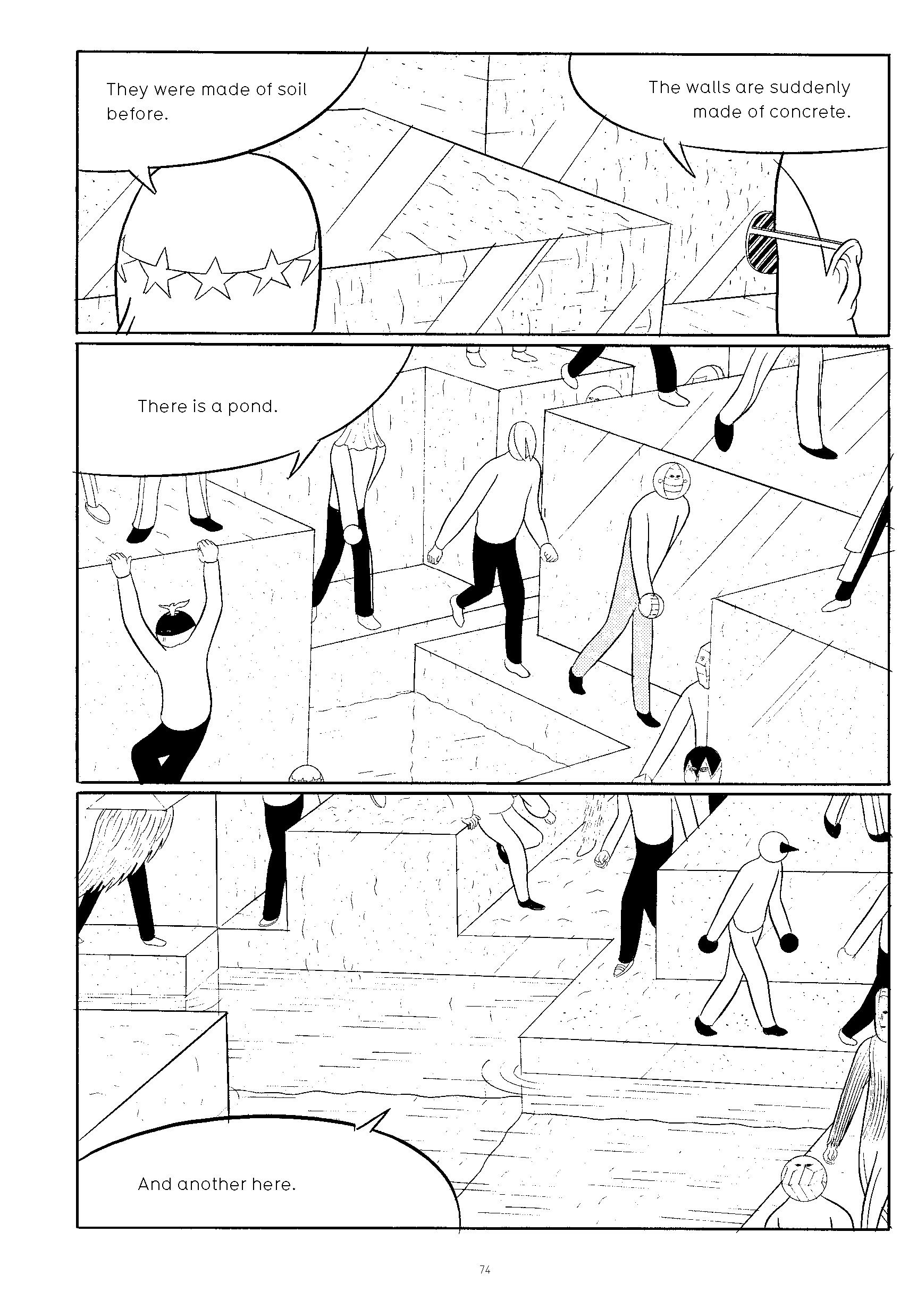

The plot of Garden is pure simplicity: A crowd of would-be sightseers (all wearing costumes and headgear that make them look like a lost Kinnikuman toyline) sneak into a sprawling "garden" filled with inexplicable, incredible sights and structures, from a river of rubber balls and a forest filled with disassembled cars to mountains made of glass and a massive hallway filled with floating bubbles. The endlessly chatty characters slowly walk, climb, swing, float, and otherwise make their way through the environments and obstacles, constantly narrating as they go. ("Now what could this be?" "It's a field of boulders." "All the boulders have ladders on them." "Let's climb it.") By explaining exactly what's happening at all times, the little explorers make following Yokoyama's often kaleidoscopic art a breeze, freeing you to simply marvel at the sheer scale and scope of his imagination (and chuckle at the the crazy stuff the characters encounter). The overall effect is like being strapped in for a ride through some Bizarro Disney World where every single attraction is as colossal and otherworldly as the big Spaceship Earth golfball, as fast as Space Mountain, and as dizzying as the Mad Tea Party.

Courtesy of PictureBox, Robot 6 is pleased to present this exclusive eight-page preview of Garden, and an interview with Yokoyama about the book, in which the cartoonist gives us some fascinating answers -- about his love for the collision between the natural and artificial, his goal in including all that dialogue, and why size matters -- and raises just as many compelling questions.

(Special thanks to Dan Nadel and Yu Marooka for their help in facilitating and translating this interview respectively.)

Sean T. Collins: The biggest change in Garden from your previous books is the constant dialogue. The characters narrate their experiences in the garden, telling us exactly what they're seeing and doing. To me, this created a sense of extreme focus: It forced me to concentrate fully on what was happening in each panel, rather than requiring me to interpret events my own way. Was that your goal in using all this dialogue?

Yuichi Yokoyama: During the events of Garden, that's the only thing that characters can do — moving around it, taking photos, expressing their view, delivering their opinion. In Garden, I would like to draw scenes where the humor comes from how the characters talk and express their own view. Of course, such dialogue by the characters helps readers understand the story easier.

That's true! I found it much easier to follow what was happening, thanks to the characters' explanations; this made reading the comic much less stressful and much more enjoyable. I felt like I was going along for the ride with them. Did you have the readers' understanding in mind when you wrote the dialogue?

In my recent stories, I always try to make dialogue and explanation as simple as possible, so that readers can understand easily. Although I am not sure if my plan is successful or not.

I think it worked perfectly. To talk about your older work for a moment, in New Engineering, you showed us man-made versions of nature -- giant machines building mountains and fields and rivers and so on. You did this in Garden as well, but you also showed us the reverse: Man-made objects becoming integrated into nature, like the cars buried in the forest, or household items floating down a river. Those features of the garden seem like a different approach to the tension between the natural world and humanity's desire to exercise control over it than, for example, the fake mountain ranges and lakes...

As you say, I can say that Garden is the story in which I showed my desire for the natural world. I enjoy seeing the natural world mixed with artificial things made by humans much more than just seeing the natural world itself.

When in your life did you first realize this? For me, seeing big treehouses for children was the moment when I realized how fascinating the mix of natural and artificial could be.

I can't identify when, but I was impressed by seeing dams and construction sites when I was younger.

At times, Garden reminded me of going to a theme park and playing around on rides and exhibits. For example, when the characters ride up the mountain on a moving block of stone, or climb up trees and slide down poles to get from place to place, it made me think of Disney World, almost. And Disney World itself is a Garden-like environment, where people created a vast artificial playground in what was otherwise wilderness. Were amusement parks or theme parks on your mind when you created Garden?

No, I never had such idea or images when I created Garden.

In addition to the kinds of natural and artificial features we're accustomed to seeing in large scale -- mountains and bodies of water, buildings and walls -- Garden also featured photographs, books, and household furniture used in such quantities that they became massive features of the landscape themselves. Why did you choose to make these intimate objects so monumental and intimidating?

I didn't intend to choose to make them so monumental and intimidating, but I would like to enjoy such common and familiar objects by giving them other different meanings of existence. Also, I always yearn for large scales, massive spaces, and huge objects.

I can tell! Actually, the sheer size of all the places explored by the characters left me wondering who or what could possibly have constructed them all. Do you ever give any thought to the architects and builders who create these spaces within the story, or do they simply exist?

They simply exist. I don't have any background on who created them.

Finally, I noticed that the characters ask many questions that remain unanswered. They never find out why the objects they encounter were built the way they were. They never find out about the mysterious person who seems to have arrived at some of these locations before they did. They never find out what lies along the paths they don't take. Are there answers to these mysteries?

There never are answers to these mysteries, so I would like readers enjoy imagining by him(her)self. These objects and events seem to be artificial, but they aren't made for human use. There are no intellectual explanations for them.

I think it's in our nature to seek explanations in fiction, but so much of your work seems designed to be beyond explanation. What are you trying to accomplish by denying readers these answers?

I believe that it's more natural that everything doesn't have explanations,

and I think it's unnatural to give readers rational explanations for everything.

---

Garden

Release Date: 5/4/2011

Writer : Yuichi Yokoyama

Artist : Yuichi Yokoyama

Manufacturer / Publisher : Picturebox

Diamond code : MAR111221

ISBN : 9780982632710

A group of friends attempts to enter a garden just beyond a wall. When they succeed, the garden they finally enter is no Eden, but rather a massive landscape of machines, geometric forms, and all manner of nonorganic objects. In Japanese comic-book artist Yuichi Yokoyama's newest and longest work, his characters become enmeshed in a fantastic wonderland of distorted mirrors, photographic equipment, massive libraries and complex pathways, thus yielding a reflection on the myriad ways human interact with the complex mechanical world we have created.