For over three decades, when it came to comics, editor Diana Schutz was the name to know. The editor's editor, Schutz has spent her career working with some of the industry's biggest creators on some of the most influential comics of all time, from Will Eisner to Frank Miller, from "Cerebus" to "300" to "Usagi Yojimbo" and more.

But after twenty-five years editing at Dark Horse Comics, Schutz is moving on -- or, as she said with a laugh while discussing her announcement with CBR News, "No more twelve-hour workdays chasing after deadlines!"

Announcing her retirement in our exclusive interview, Schutz spoke with CBR about the decision and her career, from her comic shop beginnings to joining Dark Horse and helping grow the company into the publisher it is today. While there is much to be said, we'll let Schutz explain it in her own words as we look back on her work, her decision to retire, and her hopes for Dark Horse and the industry as a whole.

CBR News: March 5 marked your twenty-fifth anniversary with Dark Horse. I know in the past you've said that editing was first and foremost in your wheelhouse, and you were less interested in creative work, plus you've been doing a lot of teaching. What led to the decision to retire, and are you using retirement as a chance to do more creative work and move away from being an editor to work on your own personal writing projects?

Diana Schutz: No, there aren't any "personal writing projects" waiting in the wings. As you say, I've always been an editor, first and foremost. Too many wannabe writers end up as editors almost by default, and I'm definitely not one of those. My primary focus has always been editing; I honestly enjoy working with writers and artists to help shepherd their vision and to make good comics. And I've been lucky: I've worked with some very talented people and by all accounts been a fairly successful editor.

But Dark Horse has changed through the years. It's grown a lot larger than the ten-person operation that Bob Schreck and I joined in 1990, and even though that growth is the mark of a successful company, I'm personally more comfortable in smaller situations. And I've changed through the years, too: my own tastes have shifted and evolved, and now at age sixty, after literally a lifetime of editing, there are definitely some other interests I'd like to pursue, mostly academic ones.

In fact, when [Dark Horse President] Mike Richardson first moved Bob and me to Portland in 1990, I went to grad school at night to get a Master's degree in Communication Studies, because at the time, that was my only way into academic study of comics. This was before Scott McCloud had written "Understanding Comics," which is what kick-started the development of Comics Studies in the universities, so there wasn't much of a scholarly scene at all back then.

And in 2002, when I first started teaching my Comics Art & Literature course at Portland Community College, I was the only game in town, but that's really changed now. A lot more Comics Studies courses and programs and even degree programs are being offered all across the country, and I love that I helped pioneer that here in Portland -- and also rallied other industry pros to share their expertise, like Brian Bendis, who's been teaching Writing Comics since 2009, and now Kelly Sue DeConnick. I mean, forty years ago, when I was getting my Bachelor's degree, I would've died to take comics courses like the ones we're offering, so it's pretty exciting to kind of pay that forward. And with all the new teaching -- and learning -- opportunities available, I want to flex those muscles a little more than I've had time for in the past.

And yeah, I also want to slow down a bit. No more twelve-hour workdays chasing after deadlines! Losing my friend and colleague Kim Thompson a couple years ago, and then my father just two months after that, was a serious wake-up call.

Remembering Fantagraphics' Kim Thompson

Since you started in the early '90s at Dark Horse, the scope of independent comics and comics culture has grown exponentially. As someone who's lived those changes, what are your thoughts on the many independent publishers that have sprung up or achieved success in recent years versus your work in the '80s and early '90s?

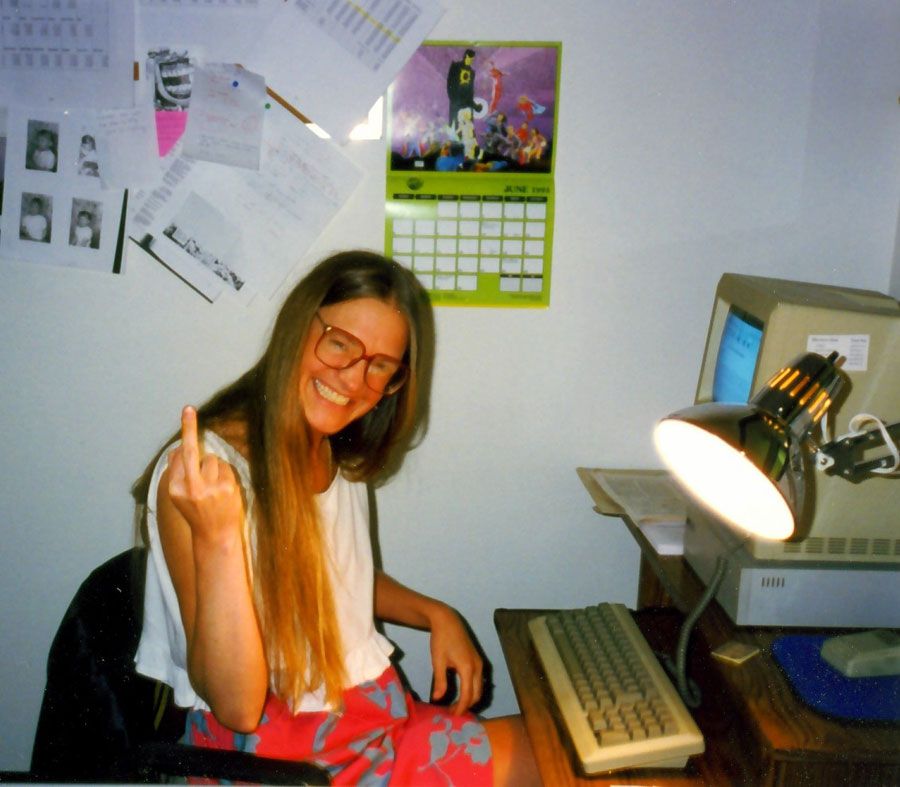

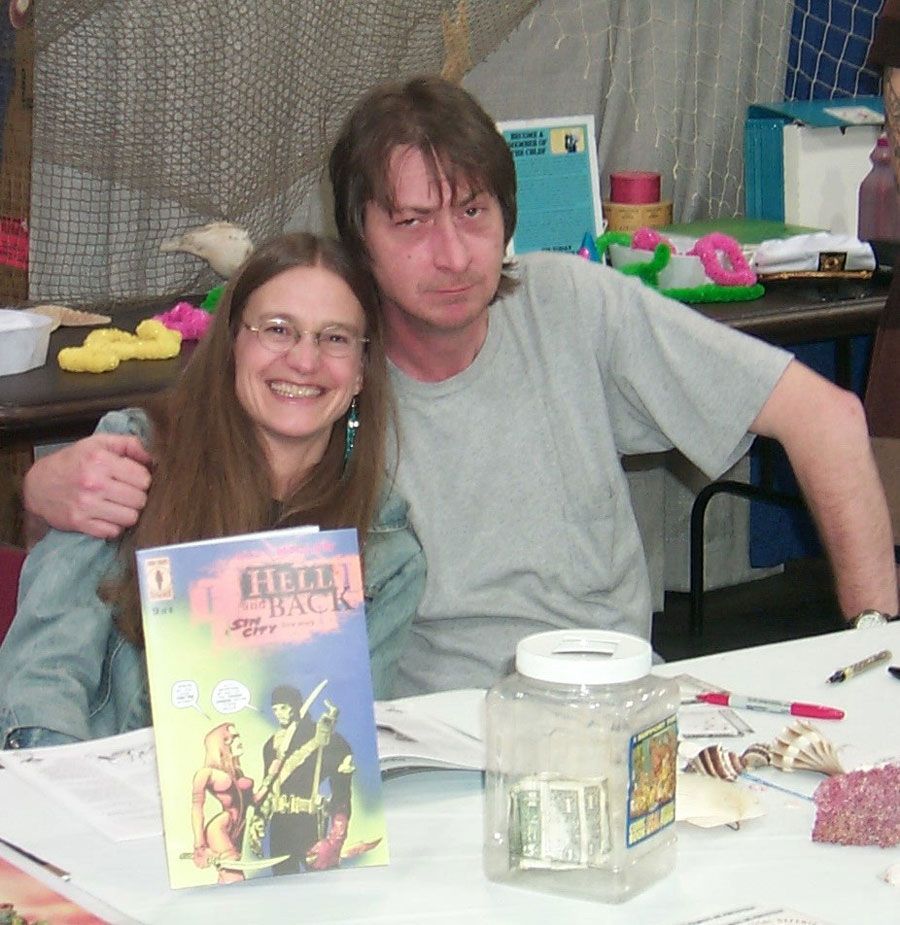

Well, my very first job in comics was even before that: in 1978, at The Comicshop in Vancouver, British Columbia. I started there during the early years of the direct market, and was one of only a few women working behind the counter of the comic book store -- one of only a few women shopping at the comic book store! [Laughs] But there wasn't a lot of choice available when I first came back to comics as a twenty-year-old in 1975. It was seeing Steve Gerber's "Howard The Duck" on a spin rack that turned me from a casual reader into a committed fangirl, because "Howard" was so wildly different from the usual run of spandex series. But in those years, your reading choices were pretty much limited to Marvel and DC. I didn't get turned onto undergrounds until I started working at The Comicshop, which is when I also discovered the self-publishers: Wendy and Richard Pini on "Elfquest" and Dave Sim on "Cerebus" (Who knew, when I read that first issue of "Cerebus," that years later Dave and I would be an item?). But in terms of the incredible amount of great comics and graphic novels that are being published today: no comparison! I bankrupt myself every week at my local comics store because there's so much to read -- and I'm not even the target demographic. It's amazing, and gratifying, to see how the medium has grown, not only in content, but in experimentation and form as well.

Looking at your career, it feels like you can play six degrees of separation from Diana Schutz with almost every big independent comic book creator: you've worked with Frank Miller, Stan Sakai, Paul Chadwick, Dave Sim, Matt Wagner, and the list goes on and on. Do you feel the work you did at Dark Horse helped create this space where we now have Image and Fantagraphics and Top Shelf/IDW and all these other publishers successfully competing with the "Big Two" and bringing in new readers?

To some extent, that's for other people to decide. Dark Horse was founded in 1986, following in the wake of other companies like Eclipse Comics before it, and Comico and Fantagraphics, what in the 1980s we called the "independent" publishers -- meaning independent from Marvel and DC, not necessarily independent in content. All these publishers were "independent" in that we were committed to offering royalties to creators along with ownership of their own characters and intellectual property. In 1977 when Dean Mullaney founded Eclipse Comics around that specific creator-friendly mandate, it was virtually unprecedented in comics and certainly unheard of at the "Big Two." And Eclipse set the standard for all the other independent publishers to follow, including Image and Top Shelf in the '90s. Dark Horse's great success, I think, is that it survived the volatility of the marketplace, and continues to survive thirty years later -- and that's entirely due to Mike Richardson.

Let's talk about your part in all of this, going back to your first comics job. I know in Canada you were getting your philosophy degree, so what made you leave academia to go stand behind the counter of a comic book shop?

[Laughs] That's a lot of years ago! Well, you know, I was reading Bertrand Russell and Immanuel Kant for school, so on the weekends I'd kick back with Stan Lee and Jack Kirby. Same stuff in a lot of ways! At first I was buying old Marvels at secondhand bookstores, for a nickel apiece, but then I discovered The Comicshop -- an entire place dedicated to comics and the people who shared that passion. I found my tribe! [Laughs] It really was like finding a home. So in 1978 I dropped out of philosophy grad school, went to work at The Comicshop, and never looked back. Ron Norton and Ken Witcher, who co-owned the shop, changed my life.

Before Dark Horse you worked on "The Telegraph Wire" and then with Comico, and though you've described your editing history as "eclectic," it always seems to center on working with creators who have a very strong aesthetic or a very specific message or point of view on what they do. So what was the draw for you to move over to Dark Horse back in the '90s?

"The Telegraph Wire" was a "newsletter" for the now-defunct seven-store Comics & Comix chain in Northern California. I say "newsletter" in quotes because it ran anywhere from sixteen to thirty-two pages, more like a fanzine and loosely modeled on "The Comics Journal." It was my baby -- and birthed before the dawn of the personal computer, so everything was typed up by hand, my hand, and pasted up in old-fashioned mechanicals. So I learned publishing from the ground up, and from there went to work as an assistant editor at Marvel, where I lasted all of four days: just long enough to learn how comics production schedules work. [Laughs] An invaluable skill, really. After that I was hired by Comico, where I was Editor-in-Ehief from 1985 to 1989.

When Bob Schreck and I left Comico in 1989, the comics industry was a very different place. If creators wanted to work for Marvel or DC, they had to sign away any claims to copyright, period. Vertigo didn't exist. The independents had come pretty firmly into being by then, providing a new publishing model in response to some vocal creators standing up for their rights: people like Frank Miller, Alan Moore, Bill Sienkiewicz and a raft of others. When Dark Horse offered Bob Schreck a job, with me in tandem since we were married at the time, DC had also made us a serious offer. But we chose Dark Horse because it was, first of all, a small company. There were ten people! [Laughs] We all worked out of one big room, so the vibe was a good one: friendly, committed, everyone was into making good comics. The appeal was to get in on the ground floor and help build a company that we really believed in.

And just as important: Mike Richardson founded Dark Horse on the principle of creators' rights. The company paid royalties and offered ownership to writers and artists; these were all political ideals that were really important in the industry and weren't taken for granted back then as they are now. Many of us felt very strongly that creators had not been getting treated properly by the corporate superhero publishers. So it was politically important to us to go with Dark Horse because of the company's stance towards creators and the opportunities it offered creators.

You've always said that your stance on editing is that you're not telling the creator what to do, you're not changing the content, you're there to make sure it's grammatically correct and put their vision forward. Did those political views influence your editorial philosophy and how you approached your work?

Sure. I think a smart editor just hires the right people and then gets the hell out of their way! In those days, with the exception of the late, great Archie Goodwin, editors tended to get bad raps. That's because they were editing work owned by their corporate bosses, and they were paid to toe the company line. When I finally started working with writers and artists to make comics -- and especially comics that they owned -- I wanted to undo that bad rap and give creators an editor they could trust, someone who would stand up for them in the face of publisher greed. And someone who would not "interfere" with the work so much as shepherd it. Ultimately, that means giving the creator as much, or as little, as they want from an editor, and backing off when it's time.

I'll illustrate this with a quick story, one that taught me an early lesson. Sometime in the mid-'80s, I was working with Matt Wagner on a "Grendel" script that he'd written for, I think, the Pander Brothers to draw. Matt and I always had marathon conversations about each of his scripts, going over every single change I thought should be made, right down to the last comma. And I'll never forget the discussion we once had about a word I felt he'd used incorrectly. We must have spent twenty minutes going back and forth about that one single word! I was trotting out dictionary definitions, grammarian-style arguments, you name it! [Laughs] Finally, Matt just said to me, "Di, it's my book." Well, end of argument, you know? Because yeah, it is his book! For better or worse, when you're working with creators who own their own material, that really is the bottom line: as editor you can provide feedback, but in the end it's up to them to take that feedback -- or not. And you let go your own ego, 'cause it's not about you. That's what creator ownership means, and that's the political underpinning of my own editorial philosophy, something I've tried to live up to as much as possible.

Like Matt, who is your brother-in-law, many people you've worked with were friends or you knew beforehand. Were there projects that you felt you couldn't be objective about, or would have a hard time editing, because of personal connections?

Well, Matt and I had already worked together for a few years before he became my brother-in-law, but your question's a good one. It was particularly telling in the case of Frank Miller, because Frank and I had been good friends since 1981 when we first met in Berkeley.

A little digression here: the comics biz was so much smaller in the late '70s and early '80s that you honestly could get to know everyone. And that's why there are those six degrees of separation, not just for me, but for most people of my generation who worked in that small pond in those early years of the direct market.

Anyway, in 1994, when I became Editor-in-Chief at Dark Horse -- a job I hated, by the way, because it meant I couldn't edit anymore -- Frank asked me to assign Bob Schreck as his editor, and they worked really well together, but when Bob left Dark Horse at the end of '96 to found Oni Press with Joe Nozemack, Frank called and said, "Diana, you have to be my editor now." But we'd been friends for so long at that point that I was nervous about potentially screwing that up. I didn't want to lose our friendship, and beyond that, how in the hell do you edit Frank Effing Miller? Frank said, "Let's give it six months and see how it goes." Six months turned into more than a decade! [Laughs] And we're still friends all these years later.

I've felt that way, incidentally, more than a few times: like, how do you edit Harlan Ellison? Or Neil Gaiman? An honest-to-god Pulitzer Prize winner like Michael Chabon? Or the late, great Will Eisner? The answer is: you just do. Will was the only person on that list who wasn't already a friend before we began working together, but we grew very close very soon afterward. Sometimes that actually makes the professional relationship easier, more relaxed.

Now that you're on the cusp of retirement, what do you feel is your proudest contribution to Dark Horse?

The master schedule! I shouldn't admit to that: it's the bane of every editor's existence! But when I first started at Dark Horse, the company was so small that they didn't even have production schedules. And in those early years, keeping the trains running on time was kind of a hit-and-miss proposition at Dark Horse. When I got there, they'd been soliciting for "Aliens Vs. Predator" for over a year and hadn't been able to deliver the first issue, let alone the rest of the original miniseries. Mike told me I had four months to get "AvP" #1 published and into stores, and I did it. That was real trial by fire, all right!

And I did it by setting up the system of individual schedules for all DH books, as well as the overriding master schedule, which incorporates those individual creator deadlines, along with in-house editorial and production deadlines, plus the printer deadlines -- for everything. Of course, twenty-five years ago Dark Horse wasn't publishing nearly so many titles; nowadays their master schedule has had to morph into a giant, complicated affair, and Scheduling is its very own department.

Aside from having contributed to Dark Horse's growth, really just by virtue of having been hired early in the company's history, there are many moments to remember, and they all have to do with a certain pride in the work itself. For instance, 2014 marked my thirtieth year as editor of Matt Wagner's "Grendel." And, in 2009, I edited my one hundredth issue of Stan Sakai's "Usagi Yojimbo" (issue #122). Those milestones are personally significant, especially for comics publishing, which is still a relatively young industry.

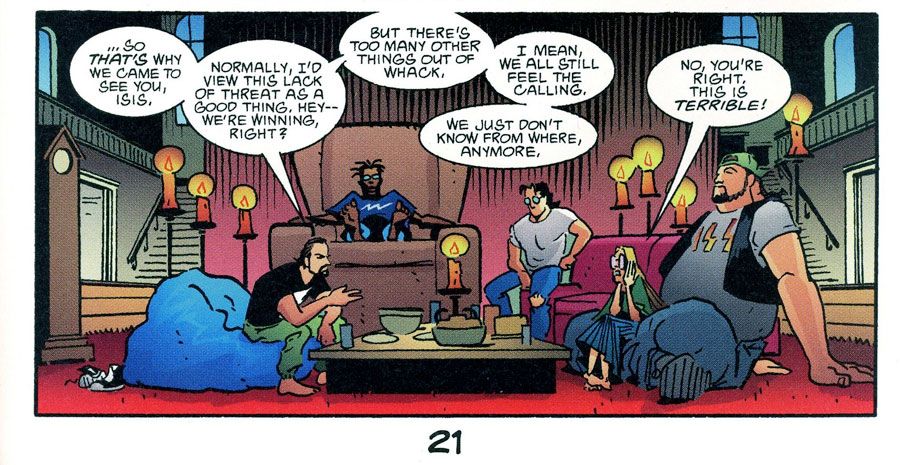

I'm proud that, back in 1999 or 2000, I began nurturing the talent of two then-unknown Brazilian artists, twins Fábio Moon and Gabriel Bá, who would eventually go on to become very successful in the U.S. comics market and whose "De:Tales" is a favorite of mine. Really, I've had the great good fortune to work with so many talented creators -- some too briefly, like Brian K. Vaughan or Glen David Gold, and others, happily, for years, like "Watchmen" co-creator Dave Gibbons or "Concrete" creator Paul Chadwick. By the later '90s, my focus was almost entirely on creator-owned projects -- for which I'm enormously grateful to Mike Richardson, because that's where my heart was and is -- and that allowed me to edit the kinds of projects that are more idiosyncratic and less traditional than most monthly floppies, like the beyond-eclectic "Beanworld" by Larry Marder; the "AutobioGraphix" and "Sexy Chix" anthology books; Farel Dalrymple's "Pop Gun War," Rick Geary's "The Adventures of Blanche," Gilbert Hernandez's "Loverboys," or Paul Hornschemeier's heartbreaking "Mother, Come Home," not to mention "The Oddly Compelling Art of Denis Kitchen" and Jeff Smith's "The Art of Bone." All of these are highlights of my time at Dark Horse -- and there are more, like ten years as editor of Harvey Pekar's groundbreaking "American Splendor" or the more recent work I've done on European graphic novels in translation, like the beautiful "Blacksad" books or the comprehensive, multivolume "Manara Library." I've been very, very lucky.

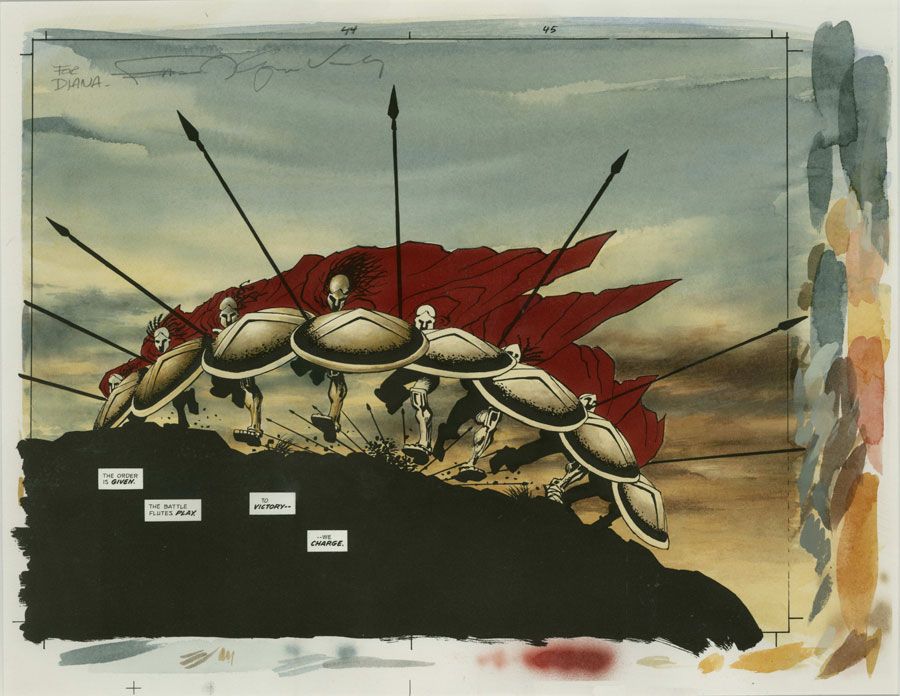

And I feel badly for younger editors who will never know the joys of working with original artwork now that comics publishing is moving into almost exclusively digital environments. Frank Miller and Lynn Varley's "300" was another high point of my editorial career, in part because nothing could ever match those days when either Frank or Lynn would ship an issue of "300" art to me. Frank drew every one of his black-and-white pages as double-page spreads and at twice-up (meaning twice the size of reproduction), so these gigantic inked pages would come in to the office in gigantic Fed Ex packages -- and those boards were spectacularly stark and beautiful. We then reproduced Frank's black-and-white artwork at actual publication size on watercolor paper, printing five to ten copies of each spread for Lynn to hand-paint until she was happy with one of them. Every publisher was moving to digital color by then, yet here was Lynn using traditional watercolor painting for, appropriately, a historical piece, while the rest of the industry was off chasing the future.

I'll never forget receiving that first issue of Lynn's painted colors on "300." I wept like a baby. I'm not kidding. I brought that magnificent art into Mike's office and wept! It was so overwhelming that I was literally brought to tears by its beauty. No digital file will do that.

Color-scanning technology in 1998 was not what it is now, and I remember sometimes going into the double digits -- fourteen, fifteen, sixteen, once seventeen rounds of scans on a single page -- before I was finally satisfied that the scan had indeed captured the exact look of Lynn's color. I probably worked harder on "300" than anything else, and in many ways I'm prouder of that than anything else, too, just because it was so beautiful and so revolutionary.

Like you've said, Dark Horse from the get-go was focused on pushing the boundaries of the medium in content, creators' rights and publishing. Looking at the industry now, what boundaries are left to push? What battles are left to fight?

If I were to stay at Dark Horse, if I still had the energy to keep fighting the good fight, I'd continue to push for more original graphic novels and more real world-based content. I'd also like to see a lot more diversity on the staff, especially in the editorial department since that's where publishing projects originate. Unless some female assistants get promoted soon, I'm leaving Sierra Hahn to carry the torch as Dark Horse's only distaff editor -- just as I had to do when I first started there twenty-five years ago. I can't speak highly enough of Sierra; she's already inherited my brother-in-law, so you know I have great faith in her editorial skill! That said, there are a number of hard-working editors and assistant editors on the Dark Horse staff -- like my own assistant, Aaron Walker -- whom I really admire. I'd just like to see a few more women in positions of authority generally, to replace the two of us who are retiring this year.

As the comics industry continues to become more girl-friendly, I see more and more women now entering the field and one result of women making publishing decisions is that there are more reading choices for women than ever before, which continues to bring more women in, and so the one feeds the other. Things have definitely changed since 1978 and my first day on the job at The Comicshop, when a customer asked the owners, "Who's the skirt?"

Given that it's been more than three decades, is there anything you'd like to say about your career, or to the fans? Any parting words?

It may sound hokey, but for people who are trying to break into the industry, well, I've been very lucky, but I've also worked damn hard. You really have to be determined to pursue your passion.

So, parting words? Yeah, work hard. And be careful what you wish for!

Diana Schutz ends her storied tenure at Dark Horse Comics on March 13, 2015.