On Jan. 6, approximately 6.7 millions viewers tuned in for the debut of "Marvel's Agent Carter." Transferring "Captain America: The First Avenger's" secret agent Peggy Carter (played by Hayley Atwell) to the small screen, the first two episodes took us back to the 1940s Marvel Universe. But instead of throwing us into "Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D."-type science-fiction plots, "Agent Carter" dropped us into a period piece, set in the sexist world of 1946 America.

"Agent Carter" is a superhero show about the postwar erasure of women from American culture -- which is incredibly fitting, as after World War II the comics industry erased women on the page and behind the scenes. As a comics community, we need to address the fact that women in comics is not a new occurrence. Women have been here since day one, a fact that is often ignored because this postwar erasure of women from our culture worked so well.

A little context to start with: The history of World War II is the history of comic books. Though invented before the war, the creation of the superhero popularized the medium and ushered in what we now call the Golden Age of comics. Through stories largely written, illustrated and published by Jewish Americans and anti-isolationists, creators put politics into their work, pitting heroes against the Nazis even while America was still uninvolved in the hostilities. Captain America punched out Hitler in March of 1941 -- a good nine months before Pearl Harbor would actually send the U.S. to war.

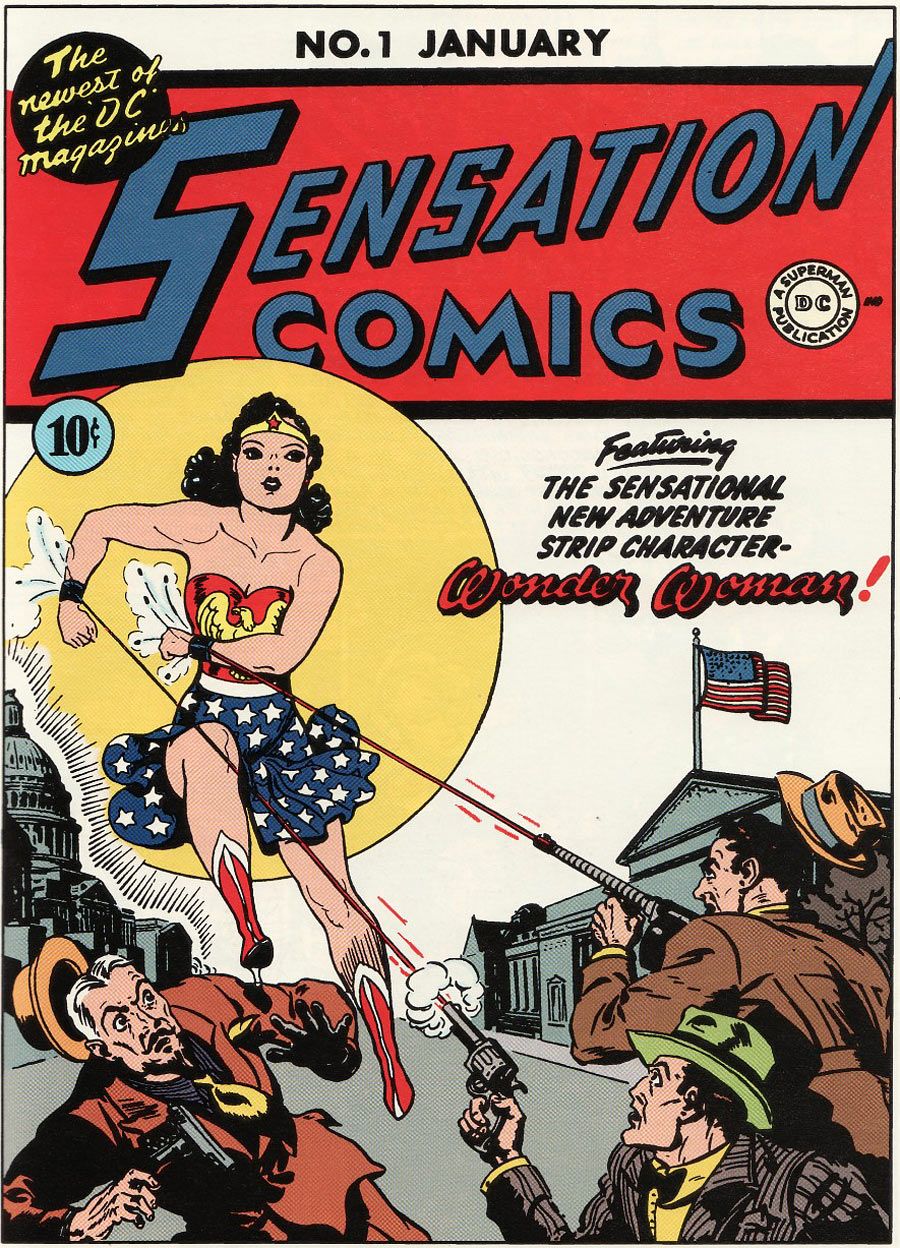

Once the war began, this propaganda became more official, with Batman and Superman selling war bonds or extolling the war effort. As real-world women entered the workforce to fill positions once held by now-drafted men -- the number of women employed in the comics industry alone tripling, according to multiple historical accounts -- fictional female crime-fighters and superheroes also dominated. Phantom Lady, Miss America (the Quality Comics character), Liberty Belle, Miss Victory, Spider Widow took up the war effort. Even existing heroes like Black Cat and Wonder Woman got involved, fighting Nazi super villains such as Wonder Woman's Baroness Paula Von Gunther.

By 1946, the war had ended and millions of women found themselves fired in favor of returning male G.I.s. It's during this messy part of history where "Agent Carter" begins. It would be easy for the show to pay lip service to the documented discrimination against women -- have a character mention someone getting fired, as Peggy's roommate Colleen does in the first episode, and then call it a day. But "Agent Carter" looks deeper, addressing the heart of the matter: That women were being told that nothing they actually did -- no matter how skilled or impressive -- was equal to what a man theoretically could do.

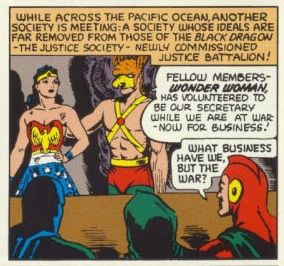

Peggy Carter is a qualified field agent, yet is made to perform secretarial work by men who are supposed to be her equals. Want to find a similar story? Just open the pages of "All-Star Comics," where the male members of the JSA are so impressed by Wonder Woman's crime-fighting they give her an honorary position -- as secretary. It wasn't until issues later that the Amazon warrior was allowed by to join the team on missions. "You have to pay your dues," waitress Angie (Lyndsy Fonseca) tells Peggy, trying to console her about work. But like Wonder Woman, Peggy already paid her dues and is still being shut out.

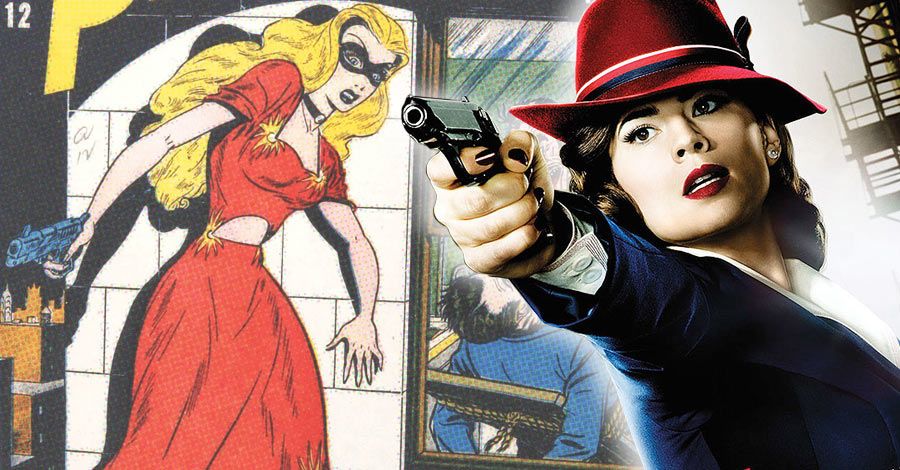

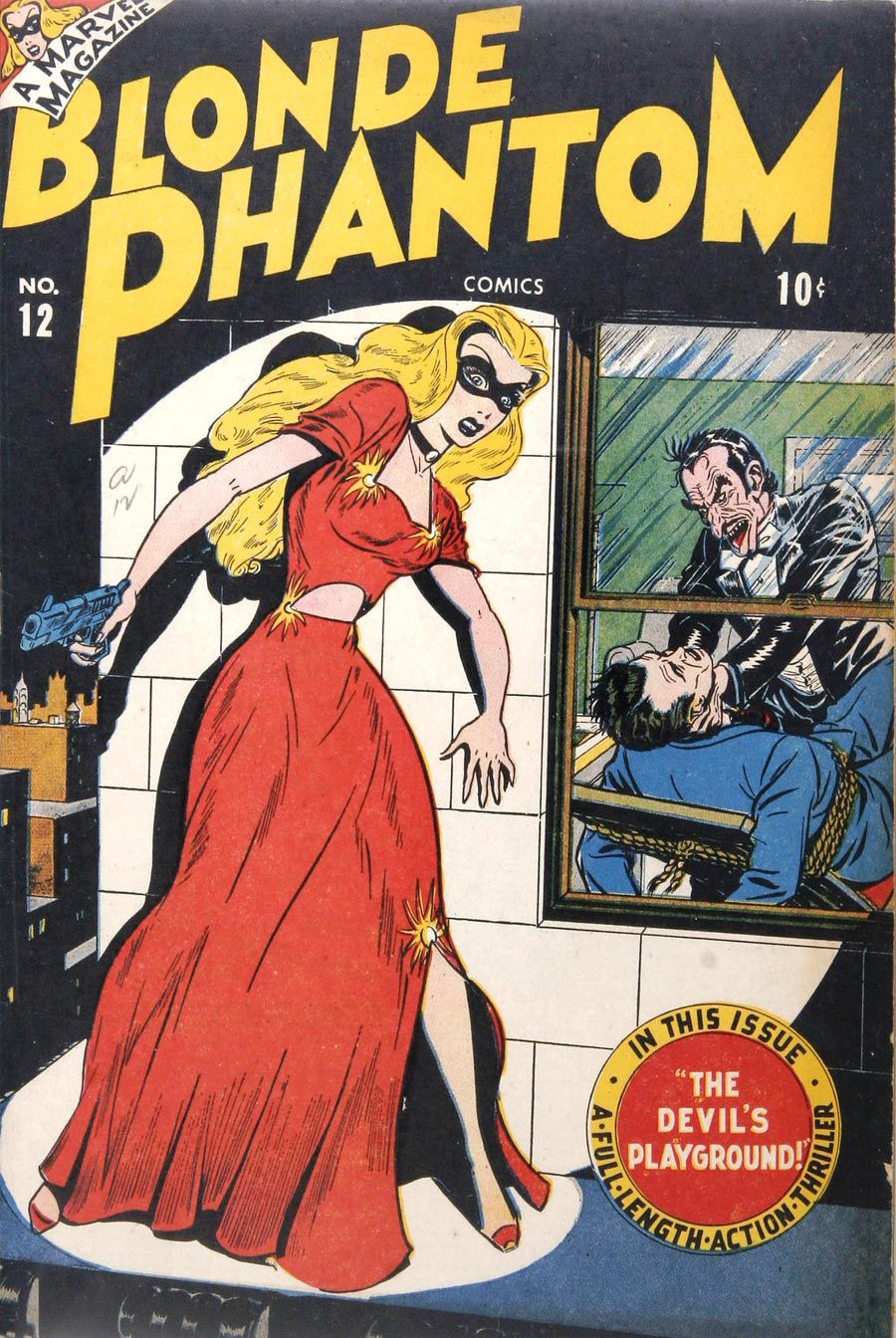

Timely Comics, the company that would evolve into Marvel, attempted to launch three new female superhero titles in 1946, the same year "Agent Carter" takes place. The only character to survive for longer than three issues was Blonde Phantom, a vigilante who donned evening wear to fight crime, and is clearly referenced in "Agent Carter" when Peggy slaps on a blonde wig and gown to go undercover. The Blonde Phantom's day job? Secretary.

It's not just the job downgrade that plagues "Agent Carter's" Peggy. She's also dealing with the pervasive attitude that woman are simply less capable then men. Peggy's boss refuses to listen to her about Howard Stark despite the fact that she personally knows him. Handicapped agent Sousa (Enver Gjokaj), while treated badly by his peers, is still the first choice for sifting through evidence on Stark despite the fact that, again, this case is tied to Peggy. It's also implied that if Peggy came clean about her covert operations, instead of getting promoted for her incredible detective work and quick thinking, she'd be fired. Male agents like Jack Thompson (Chad Michael Murray) are supposed to show initiative; Peggy is supposed to fill the coffee.

This is the attitude that led to the real world mass firings of women in the late '40s, hitting the comics industry especially hard as the numbers of women employed went back to pre-war numbers. Whole publishers such as Fiction House, which employed large numbers of women and was specifically hated by anti-comics crusader Fredric Wertham, went under. Timely would stop buying work from the Jacquet Studio, another shop that employed many women. In 1946, the National Cartoonists Society would be formed, with women finding themselves deliberately and blatantly excluded from the organization. Indeed, the organization's constitution specifically stated, "any cartoonist (male) who signs his name to his published work" was eligible for membership.

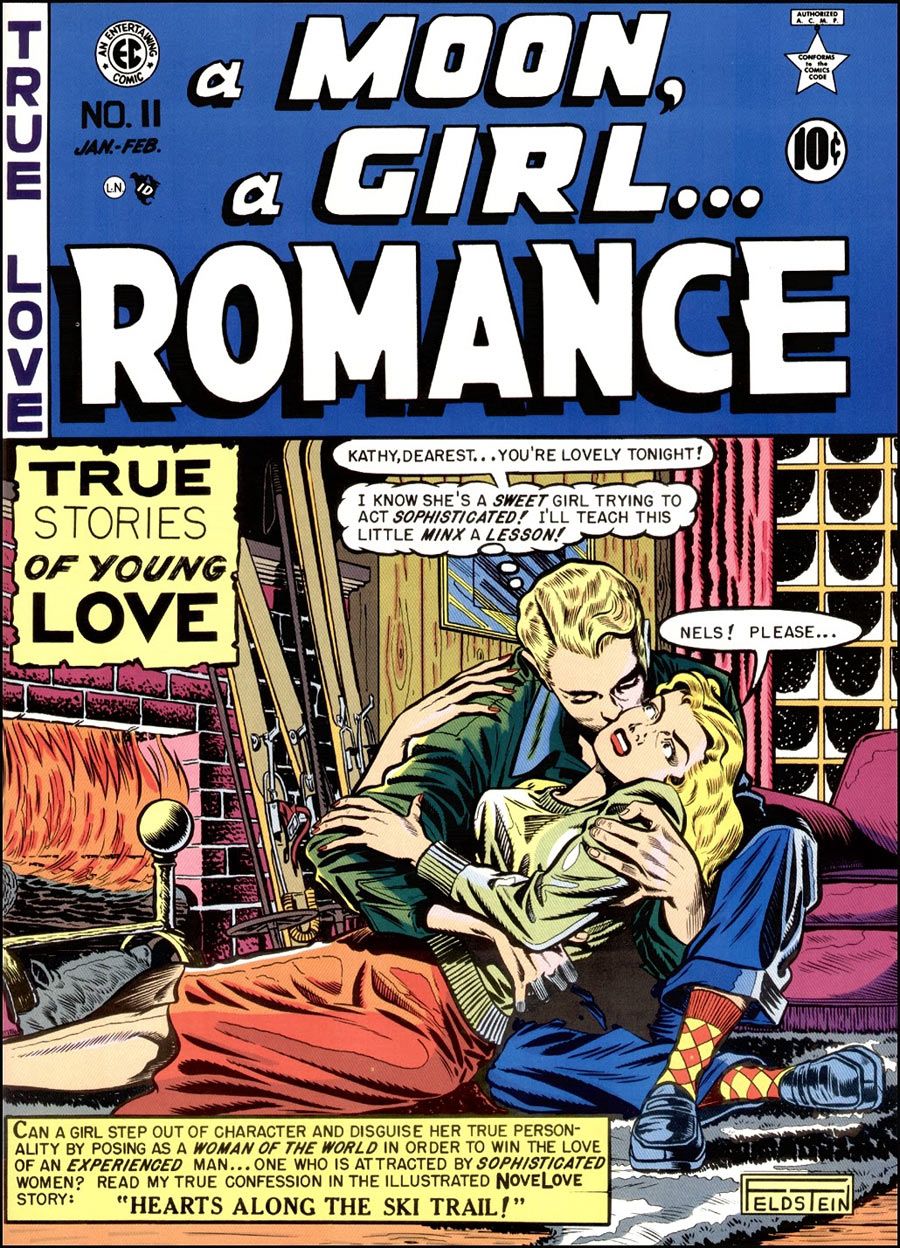

But the show isn't just playing on the misogyny of postwar America -- it is deliberately calling the media out for normalizing sexism. Just as female superheroes were turned into comic book sidekicks, the radio version of Peggy is transformed into Betty Carver, the helpless nurse/damsel in distress who depends on Captain America to save her. We laugh as Betty bleats, "If only Captain America was here to rescue me!" But when the stars of postwar comics such as "Young Love" or "Career Girl Romances" declared "I guess from now on, I'll forget my silly notion of trying to act like a man!" audiences weren't supposed to laugh. They were supposed to agree.

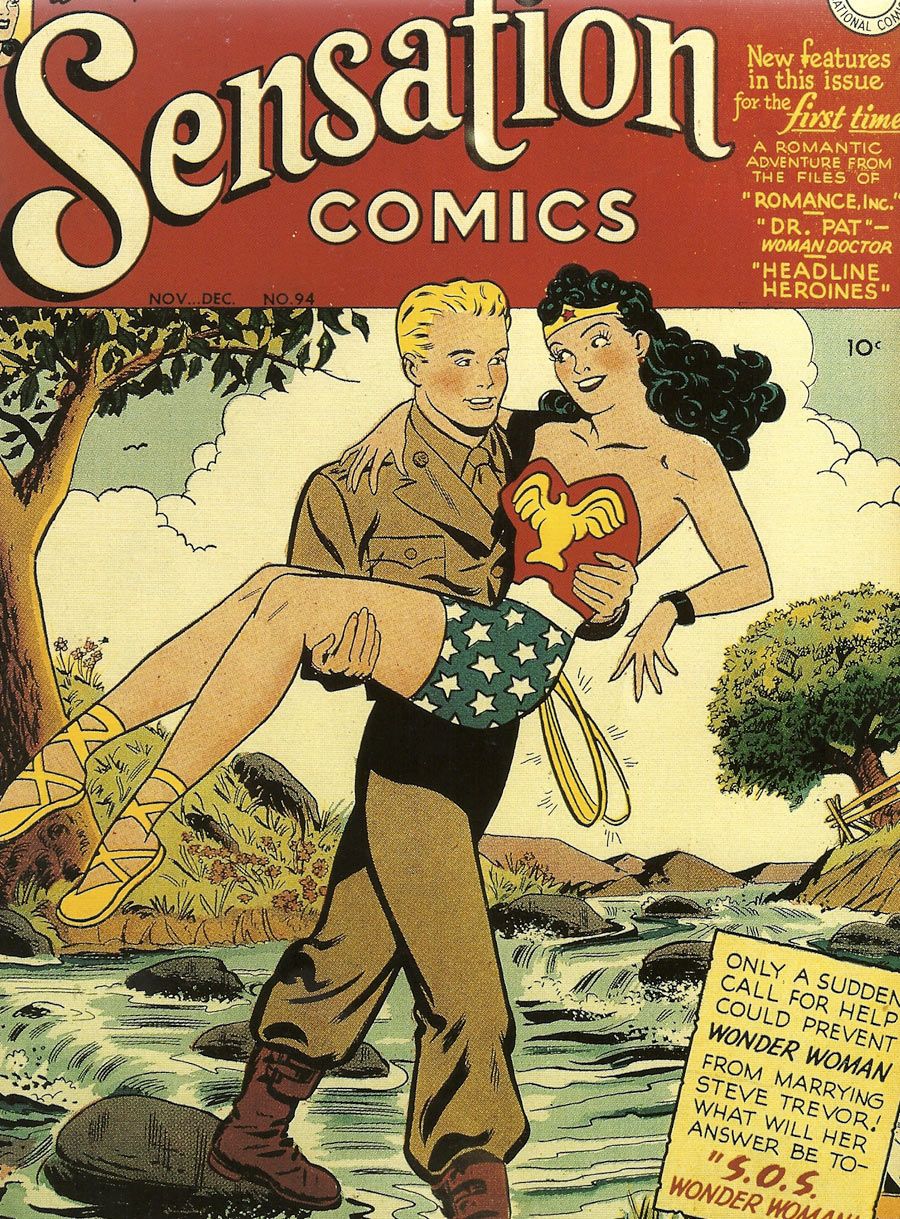

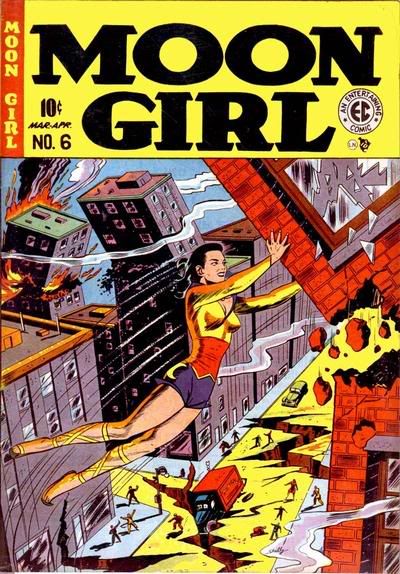

Like Peggy's role in the War was converted to Betty's hapless misadventures, female comics characters were divested of heroic elements and turned into love interests. EC's Moon Girl, star of "Moon Girl Fights Crime!" transformed into the teen love comic, "A Moon, A Girl...Romance!" Miss America, the Timely version, began life as patriotic crime fighter. By her second issue, she was relegated to the back pages as Patsy Walker, a powerless teenage girl, took center stage. Comic books literally de-powered women.

In postwar America, there was only one role for women: housewife. In episode two of "Agent Carter," Peggy gets her apartment application approved by "correctly" answering she plans to work "only until I'm married." Betty Carver is always identified on the radio show as Captain America's main squeeze, which, in turn, is all anybody knows about the real Peggy Carter. The heroes of the postwar era weren't sophisticated female spies or competent women who existed in their own right. They weren't women at all. They were girls: Sun Girl, Hawk Girl, Supergirl. Even into the '60s, they existed as an extension of men: Invisible Girl is Reed Richard's love interest. Jean Grey does all the housework for the X-Men. Namora is Namor's cousin and isn't even named Namora. It's a codename given to her simply because she's related to him.

Most importantly, they were non-threatening. Solo female heroes largely disappeared in the face of the Comics Code Authority, which upheld "traditional" roles for women and men. To quote excerpts from the section entitled "Marriage and Sex":

(1) Divorce shall not be treated humorously nor represented as desirable.

(2) Illicit sex relations are neither to be hinted at nor portrayed. Violent love scenes as well as sexual abnormalities are unacceptable.

(4) The treatment of live-romance stories shall emphasize the value of the home and the sanctity of marriage.

Got that? So no swinging single ladies, no LGBT characters and if a woman is a love interest, she had better constantly talk about how she wants to get married. This exact dynamic played out in "Superman's Girlfriend, Lois Lane" as well as basically every other Silver Age supporting female character's every appearance. Oh, and no pants, ladies: "All characters shall be depicted in dress reasonably acceptable to society."

For further context, here's a quote from Wertham, that foremost postwar anti-comics crusader, grousing about how women in comics are bad role models: "They are not homemakers. They do not bring up a family. Mother-love is entirely absent."

But even woman's sanitized, domestic role was seen as lesser. A housewife was worth less than a career man. An unmarried woman wasn't worth anything at all. On "Agent Carter," Peggy's coworkers deride her for her involvement with Captain America. Her boss insinuates that she's a slut in front of the entire office, stating that Peggy undoubtedly found out a lot "being Captain America's...liaison." Agent Krzeminski (Kyle Bornheimer) instantly chuckles to his fellow male agents, "Sounds like Carter knew a lot of guys during the war."

I could compare Peggy being reduced from human to sex object in 1946 to characters like Phantom Lady finding her comic turned into a cheesecake title in 1947, but I don't need to go back in time for that. Go check out the Wikipedia pages of Venus, Miss America (DC/Quality), Phantom Lady and Namora; unless some kindly soul has edited them since, as of this writing, the opening blurb explaining the important details for each one (publisher, creators, etc.) also includes the fact that they all ranked in the Comic Buyer's Guide's "100 Sexiest Women in Comics" list.

And that's the issue. The propaganda role comics played didn't end with the war. It continued with the deliberate, sexist changes made to women in comics in the late '40s and early '50s. Captain America punching Hitler before the war even started sent a deliberate message to readers, and so did changing the 1940s Wonder Woman feature "Wonder Women Of History" into a section called "Marriages A la Mode."

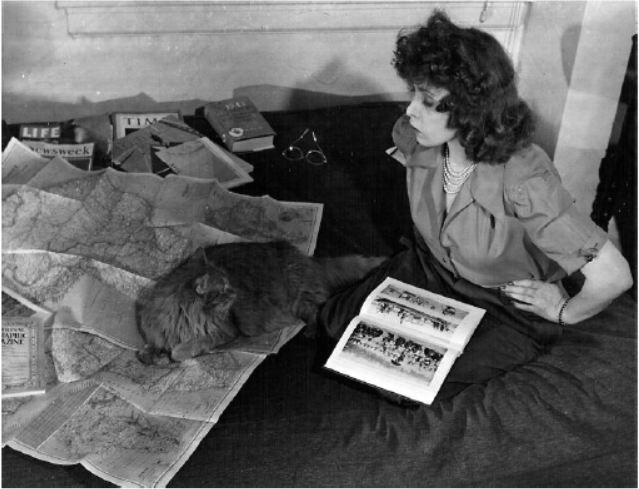

But while fictional characters could be changed, the women colorists, inkers, scripters, letterers, writers and editors were simply kicked out. Quick:, name three people working in comics industry during the Golden Age. Was "Miss Fury" creator Tarpe Mills one of them? What about artist Ramona Patenaude? Josephine Elgin, who inked "Kid Eternity?" Alice Marble, who assistant edited "Wonder Woman," or Elizabeth Burnley Bentley, who did letters and backgrounds for Batman and Superman? I'm betting that, for most of you, this is the first place you've even heard of them. We act as though the history of comic books is the history of male creators writing male superheroes because the postwar erasure of women worked. What has no worth has no place; what has no place will be forgotten. Say that women are worthless and their contributions become worthless as well, easily forgotten and hidden away.

Problems with female representation in comics still exist today. In 2018, Marvel will release a Captain Marvel movie -- after 10 years of Marvel movies headlined by male characters. Wonder Woman will finally get her big screen debut in 2017. That is, if DC and WB don't scuttle the plans for it as they did in 2007. Or throughout the '90s and 2000s, which saw the studio go through at least seven different scripts and creative teams. And that's not even counting the 1966/67, 1974 and 2011 failed pilots.

But the biggest problem facing us as a comics community is the fact that we act like women reading and creating comics is a new phenomenon. That social justice conversations are a modern creation, facilitated by the Internet. This is demonstrably not the case. Women's involvement in comics is literally as old as comic books themselves. "Agent Carter" is giving us a chance to address our guilt and recognize the women who built the medium, and they're doing it within our genre, our characters, our culture. But if we can't recognize this as a community -- if we cannot address the fact that women have always been part of our comics culture -- then we'll erase the contributions of women more thoroughly than any postwar policy ever did.