Nine years after Will Eisner's death, comics' biggest names remain in awe of the legendary creator's talent. And one of them is still in awe -- in a negative way -- of Frank Miller's cinematic homage to the late creator.

"Is there anyone in this room who actually liked the 'Spirit' movie?" veteran writer Peter David asked the audience attending Emerald City Comicon's "Why Eisner Matters" panel. Seeing no hands raised, David continued. "Okay, so we're all on the same page."

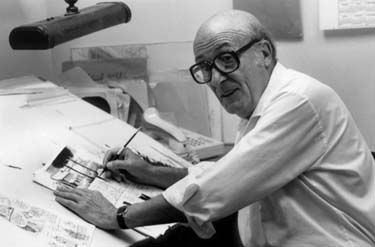

Miller's 2008 action movie is widely seen as a star-studded misfire, a bizarre take on Eisner's classic urban-vigilante comic strip that ran from 1940 to 1952. But even a poorly-received movie based on his most famous creation was unable to tarnish Eisner's legacy as a grandmaster of American comics, whether as a creator, a publisher, a teacher, an advocate or a visual artist.

David came together with writer Matt Fraction and artists Jeff Smith and Michael Avon Oeming to honor their forebear, quickly spinning off into personal anecdotes of encounters with Eisner -- or simply with his work -- which changed their careers, sending them on new, rewarding trajectories.

"When you read Eisner, it's like reading poetry to a great degree -- kind of like reading Bradbury," David said. "He draws incredible drama and pathos and agita from ordinary people -- people who have just come to this country and are trying to build new lives, people who are trying to come to terms with their own religion."

Eisner's 1978 "A Contract With God" is widely hailed as the first true graphic novel -- a term Eisner himself applied in order to open up new markets for his work in bookstores rather than relying solely on direct market comics shops. Long before that, his "Spirit" strip bent the rules of presentation in newspaper comics. He taught the lexicon of the form with his nonfiction "Comics and Sequential Art," and "Last Day in Vietnam" offered a compelling collection of war tales told in his inimitable style.

Fraction, who authored an introduction for a new edition of "Last Day in Vietnam," shared, "There's a story in this book that's so good, anyone, at least of my age -- you would break your thumbs typing and drawing it to get it out so fast. It was a true story, and he clearly waited until he had the volume of material to build around it rather than put out a short story. He knew, 'This is a centerpiece of a book about war that I want to put out.'

"First of all, that long game, I respect," Fraction continued. "To have that self-control of knowing this is killer material. He was still doing things in that book that were incredibly experimental, the stuff you don't think of, quote, 'elder statesmen' trying to do."

Well into his later years -- Eisner died at age 87 -- he remained vital and interested in the work he and other comics creators were pursuing. Oeming recalled, "He didn't want to just be nice to you. He was interested in what the title was of the thing you were working on. He was asking you questions about you."

"What was noticeable about Will was, he was still present," Smith shared, talking about seeing Eisner at cons and other gatherings, late in his life. "Will was still actively engaged in the art form, always was. He got out of it during the war, but he was in some other way following this other idea of his that is doesn't have to be juvenile crap."

Indeed, Eisner spent his Army service in World War II crafting educational comics for GIs -- like Joe Dope, a sad-sack character who routinely demonstrated how not to keep military vehicles in working order.

Little of this would have mattered if not for Eisner's consummate visual artistry, the panelists said.

"He could draw clothing so well," Smith said. "It's so hard to draw a good pair of pants."

"And all of his clothing was wrinkled," David remarked.

"As a writer, the thing I've taken from his work is a physical expression," Fraction said. "You can write an emotion into a book that a reader can hear in the tone, but you can't draw it."

"The thing about cartoons, even now -- there's only like two expressions, stern or surprised, and that's it," Smith said. "Usually, they're not that different...but Will, his characters were thinking and they were overreacting, but that kind of melodrama was fantastic. There was emotion all over (Jack) Kirby's drawings too, but those are two exceptions."

Eisner's "A Contract With God" is a moving exploration of faith delivered in comic-book form, and Fraction described "Comics and Sequential Art" "as though I had discovered the Torah."

"A lot of it is 'how to make comics the Will Eisner way,'" Fraction continued. "But that's not bad. You could do a lot worse."

Sadly, as interested as he was in innovation, Eisner didn't live to see the current era of comics publication in the online sphere, a fact Oeming regrets. "I would've loved to see his thoughts on that."