"Still, you wouldn't want to see my novel on the screen because it is full of people conversing, plus the personal problems of the protagonist. These matters don't translate to the screen. And why translate them, since a novel is a story in words, whereas a movie is an event that moves?" Philip K. Dick wrote that in 1981, discussing his novel "Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?" and the film adaptation "Blade Runner," which merely used Dick's novel as a jumping off point for a related-yet-entirely-different tale.

This quote serves two purposes: to provide a warning that fans of "Blade Runner" will be in for a shock (and a treat) with BOOM!'s adaptation of "Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?" since the two works are quite distinct. The second is to hint at the idea that a comic adaptation of Dick's novel is fraught with difficulties right from the beginning since comics, as a medium, exist somewhere between prose and film, and, as a result, certain compromises must be made despite the presentation of Dick's text unedited.

With prose, how characters and the world they inhabit look is left exclusively up to the reader, each interpreting it differently, and having an artist attempt to visualize every scene -- every sentence even! -- of a novel is going to create a tension between the adaptation and the reader no matter how talented the artist in question is. As well, having the art right next to the text will shape how the reader visualizes the text, the art acting as an influence to how the prose is received. Even though BOOM! hasn't changed or omitted a single word from Dick's novel, this is a very different experience from reading the novel.

That said, what a wonderful idea and fantastic way to introduce the work of Philip K. Dick to new readers. With the huge influence Dick has had on sci-fi and comics, his work should be mandatory reading for anyone who regularly engages either. No doubt most have seen at least one of the film adaptations of his prose, but his ideas have shaped so much of what's followed with top writers like Warren Ellis, Ed Brubaker, and Grant Morrison indebted to Dick. So, now you have no excuse, because BOOM! is putting Dick's work in comic shops this week.

Choosing to present "Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?" in its completeness is a bold decision and, no doubt, some will find it a bit cumbersome. In the first issue, the first two chapters plus the beginning of the third are presented in their entirety. This also means that word balloons are sometimes broken up by 'he said' captions, which takes a little getting used to. Needless to say, this is a text-heavy comic, but at least you won't be complaining that it only takes you three minutes to read it. The opening pages provide a good idea of what the comic is like.

This issue introduces the main characters and concepts of the novel, beginning with Rick Deckard and his wife as they begin their day with a disagreement. Where it gets interesting is how they threaten to escalate it by turning the dials on their mood-alterers to stronger emotions. Dick introduces this concept through a couple's argument seamlessly and, then, uses that to engage the larger world, which is post-fallout with the majority of humanity emigrated off Earth. Taking care of an animal is an important cultural element in this society, as is an empathic religion known as Mercerism.

Dick throws a lot of information out in these opening chapters, but none of it seems forced or heavy-handed. He understands the need to build the world for the reader as quickly as possible and does so admirably. BOOM!'s decision to end the issue shortly into the beginning of chapter three of the novel is very effective since it ends in the middle of action, teasing Deckard's job as a bounty hunter who specializes in androids.

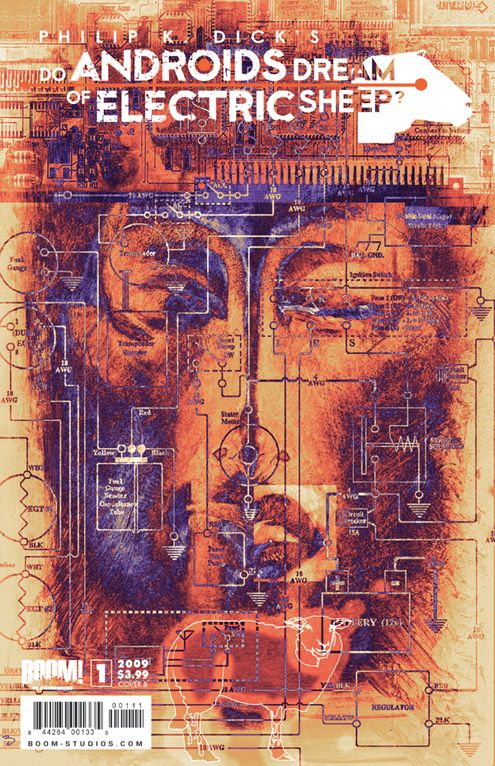

Artist Tony Parker does a solid job, for the most part. He's given the difficult, unenviable job of turning every part of Dick's writing into art -- and to do so without copying the distinct visuals of "Blade Runner." In that respect, he succeeds, going for a much bleaker and drabber world. One of grays and browns rather than nighttime and rain. His Deckard looks more average and down-on-his-luck than Harrison Ford, but also looks like a man able to hunt down androids.

In a few instances, though, Parker runs into trouble as his art directly contradicts the prose he's adapting. Dick describes Deckard's wife as wearing a long robe that trails behind her, but we get a robe that doesn't even reach her knees in typical comic book cheesecake style. Or, the change from Mercer's climb up a hill to a steep, rocky cliff. It's a little jarring.

All in all, this is an experiment that works and also contains a fabulous essay by Warren Ellis that introduces Philip K. Dick in a broader way. All in all, a great package ideal for newcomers and fans alike.