Unpredictability. For some people that's a negative trait, but in comics it can be advantageous.

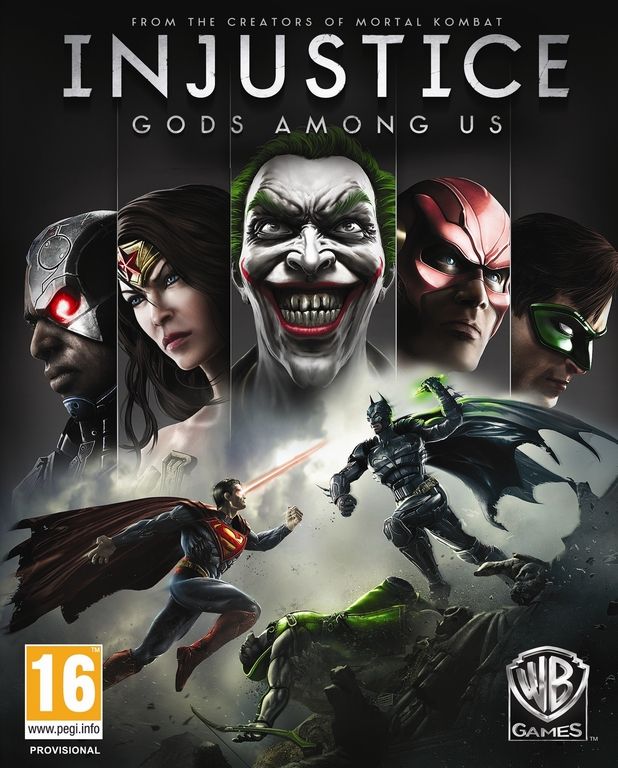

Justin Gray is unpredictable, in a good way. While some writers fall into the trap of working within one genre or one flavor of story, Gray has quietly created one of the most diverse bibliographies in comics with his frequent collaborator Jimmy Palmiotti. He's done superheroes for DC Comics and Marvel, including a celebrated run on Power Girl. He's written a variety of creator-owned work, from the early 21 Down and The Resistance at DC/Wildstorm to more biting, adult fare like Random Acts of Violence and the recently released Sex & Violence. He's also become an in-demand writer of comic-centric video games, working on DC's Injustice: Gods Among Us, Mortal Kombat vs. The DC Universe and others.

Oh, yeah, and he and Palmiotti helped to prevent Jonah Hex from becoming a footnote in comics history.

While other writers like Grant Morrison and Brian Michael Bendis might soak up most of the spotlight, Gray is quietly able to jump from one project, genre or medium to the next.

Chris Arrant: Justin, what are you working on today?

Justin Gray: I’m currently co-writing Batwing and All-Star Western with Jimmy Palmiotti for DC Entertainment. Jimmy and I helped develop the story alongside Neatherrealm for the Injustice: God’s Among Us video game featuring the DC Universe’s best-known characters, and that ships in the second week of April. Sex & Violence, a successful Kickstarter campaign that Jimmy and I put together, should be shipping in the next week or so. Based on the success of that project, Jimmy and I are collaborating on another Kickstarter as well as a handful of creator-owned and creator-participation deals that I’m excited about and can hopefully start discussing this summer. I just read through two screenplays based on properties that Jimmy and I created, one being Random Acts of Violence, written by Jay Baruchel and Jesse Chabot. I loved it. I wish I could talk about how great it is, but I can't.

Good to hear you're busy. Throughout all the comics work you’ve done in the past 11 years, you’re best known for Jonah Hex by a mile -- both in his self-titled series, a graphic novel and now in All-Star Western. What’s that like for you, being so connected to the Hex character?

I think I’m fortunate to have the opportunity to work in comics. Certainly, Jimmy and I have enjoyed a long run with Jonah Hex and hope to continue to do so for the foreseeable future. I like the fact that the book and Jonah Hex has survived in an era where content is often line-wide event-driven material. The climate of comics has shifted dramatically during my time as a professional, but the focus we’ve always had is to do the best with what we have in front of us. Sometimes we fail and sometimes we succeed, but we continue to challenge ourselves both as a team and as individuals. There are worse characters to be associated with.

Yo

u and Jimmy have ridden Jonah Hex through great times and bumpy roads, with a lackluster movie and then also the switch to All-Star Western. What do you think makes it so you’ve stuck to Hex so relentlessly?

It's funny, we can only be responsible for what we’re given in life, but we should fully accept that responsibility. When we started pitching Jonah Hex back in 2005 we were equal parts excitement and cynicism. The idea of doing a western had great appeal, but the reality was that I think two-thirds of people expected failure. We approached, and still approach, every issue like it is our last. The other funny thing is how many people have said they’d give his or her right arm to write a Jonah Hex comic. There’s a unique responsibility with a character like Hex that differs from Batman, Wonder Woman or any of the other iconic heroes. I think that was evident in the resulting changes made to the film. We understand Hex, he’s a part of us. What began as a great opportunity to work in the western genre, evolved into a cathartic exercise in violence and social anger has ultimately brought us to a point where we can comfortably tell any kind of story with Hex. That’s what we intend to do this summer.

You two recently jumped on board the DC series Batwing, not so much picking up where it was before but turning a new page on this. Can you describe what the situation was like coming aboard, and the latitude you two were given with this?

Jimmy and I approached Batwing from multiple angles. We like David Zavimbe and respect the work that both Judd Winick and Fabian Nicieza produced during the initial 18 issues, so we wanted to reflect that in this transition. The book wasn’t selling, which is unfortunate because there are important stories to be told about Africa that transcend what novelist Chimamanda Adichie calls "the danger of a single story." I think this has hurt Batwing in the same way it damaged Josh Dysart’s Unknown Soldier. Yes, there are a small number of comic fans that can appreciate, and did support, this book and the style of storytelling, and hopefully we gave them closure. From a business perspective we were given a book with low sales and asked to do our best to turn around that trend. To do that we felt it was important to bring Batwing closer to the core line of Bat-related books, to make it feel like it meant more to Batman on a personal level. I desperately hope people understand the position we’re in and give 19-20 a try. That’s all we ask.

You and Jimmy are some of the most versatile writers in comics, doing traditional superhero books like Batwing and The Human Bomb while also balancing doing licensed work like Injustice: Gods Among Us, digital-first projects like Ame-Comi Girls and also an active output of creator-owned projects like Sex & Violence. In this day and age, where do you see yourself in the industry?

Honestly? I don’t often think about where I fit into the larger landscape of comics. I might make a joke on Twitter once in a while saying I wouldn’t mind being the Gregory C. Coleman of comics, but I tend to shy away from some of the things that drive people in the entertainment industry. I think that’s probably because I worked in the service industry for years and it is vastly different from corporate, office or freelance work. By example, when you work as a chef or a cook in a restaurant everybody knows if you’re good, bad, slacking or giving 100 percent. You can’t hide behind people or blame others if things go wrong. I realize comics are a business and when I’m hired to do a job for a company I do the best job possible with the tools and resources I’m given. Even on the worst of days I’ll take “professional writer” over any other job I’ve had. Creatively I can’t see myself working exclusive in one genre or medium.

You recently started a Facebook page in an effort to organize support for DC to consider doing an Absolute edition for Jonah Hex. You’ve found a lot of support in the fan community, from the Monolith reprint to the numerous Kickstarters you’ve done. Do publishers listen to fan support, be it activity on Facebook page or numbers on Kickstarter?

Everyone says they have the best fans, and I’m no different. I can’t believe I have fans. I can’t comprehend someone being nervous to meet me, and when it happens I’m kind of bewildered. Fans are the lifeblood of every project. As for grass-roots campaigns I think corporations respond to financially rewarding situations. It's no secret entertainment companies put the bulk of their efforts behind known commodities or properties with a built-in audience. For me, on a much smaller and more personal level, a Kickstarter like Sex & Violence is like making a playlist for your closest friends. There’s an intimacy with this kind of direct to supporters creation of a book. I stood in Jimmy’s house looking at boxes and boxes of personalized packages containing our work and it felt like we were doing something important with and for the people that follow our work.

A lot of pros looked on Creator-Owned Heroes with a lot of anticipation for pushing your creators-first anthology. Although it ultimately didn’t hit the sales numbers to continue, what did you gain from doing that project?

I’m not afraid of failure. No one that worked on Creator-Owned Heroes is. I’m also not going to blame the industry, readers or retailers because that’s a default consolation that ultimately serves no purpose. The reality is there were people who appreciated what we were doing, but that number was not large enough to sustain our continued efforts. There were naysayers, some were critical of the name, but if you don’t at least try to create different things then you’ll never grow. We learned a number of things that we’re applying to other projects moving forward.

Could you see yourself doing something similar in some form down the road?

I really don’t know. In a way Sex & Violence is a progressive step following Creator-Owned Heroes. It features Jimmy and myself working independently with different artists and operating around a central theme. One of the driving forces behind our creator-owned work is quality, attempting to produce a book that looks and feels like it is worth every penny. I know that makes some of our collaborators crazy at times, but when the dust settles and you hold something like Sex and Violence you can see how much we love what we do and the people that support us.