To the average comics reader, Joe Casey is the writer behind idiosyncratic creator-owned books like Gødland and Sex and the stellar re-imaginings of corporate-owned superheroes like Wildcats, Superman and the X-Men. But to the pre-teen set, he's the co-creator of one of the hit kid-friendly animated series Ben 10 and a co-writer of Ultimate Spider-Man and the upcoming Marvel's Avengers Assemble. With two radically different profiles, the question becomes this: Which is the real Joe Casey? I'd argue it's both, and more.

Casey got his start in the shifting sands that was Marvel in the late 1990s in the years, filling in on a Wolverine miniseries before quickly stepping in to take over Cable. Much in the same way that character moves back and forth in the time stream, Casey has hopped among titles, genres and companies.

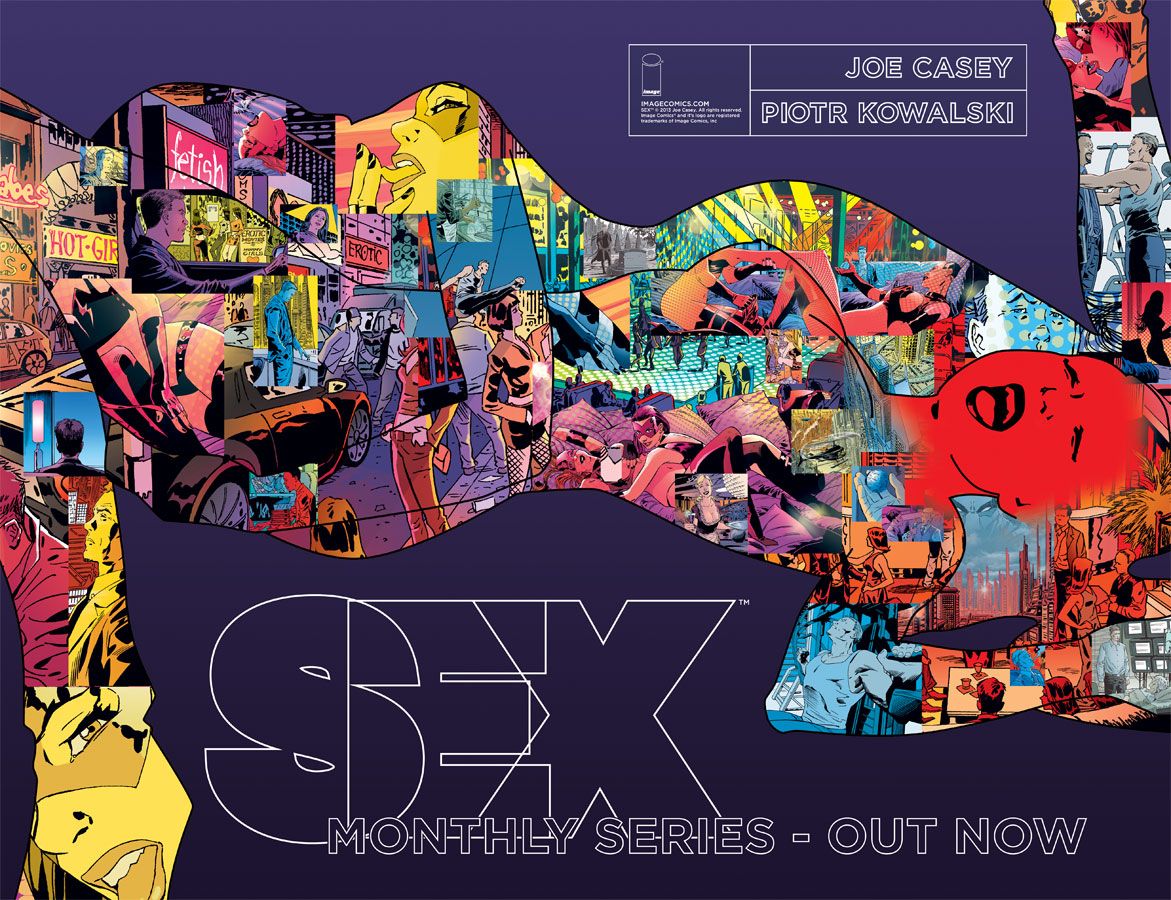

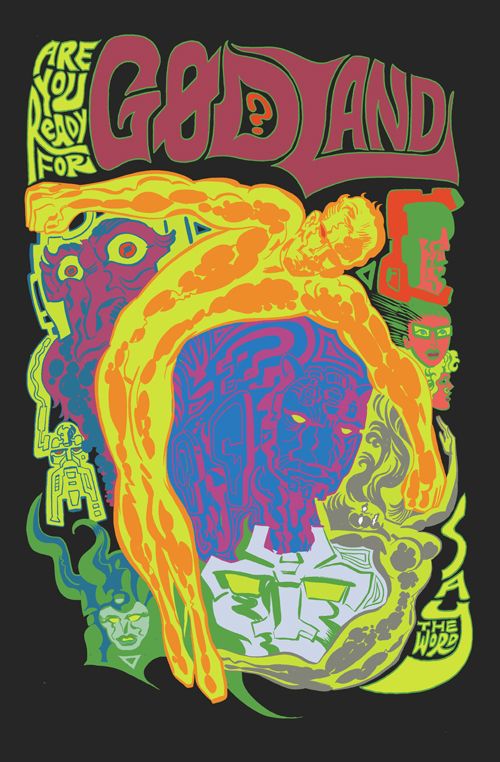

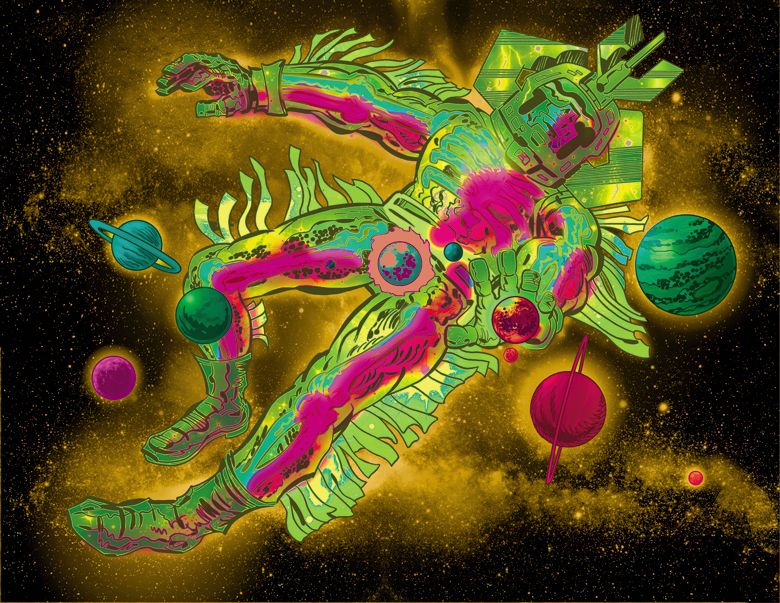

With the success of Ben 10, however, he's become more judicious about the comics projects he pursues and the people he works with -- both artists and editors. While it might result in fewer Joe Casey comics on stands every month, it allows for better Joe Casey comics, such as the current one-two creator-owned punches of the Image ongoings Sex and The Bounce. Although animation keeps him busy (and well paid), he has several other projects in the works, from the long-waited finale to Gødland to the radical re-envisioning of one of Dark Horse's superhero titles in Catalyst Comix.

Casey's success as animation writer has provided him with a different vantage point on comics, from storytelling to the audience. And that's given him big ideas.

Chris Arrant: What are you working on today?

Joe Casey: I just finished the scripts for Sex #7 and The Bounce #9. Still in the middle of writing Catalyst Comix #5. Scripting away like a madman on the Gødland finale. Also waiting for an animated Marvel's Avengers Assemble script to come in so I can read it and sprinkle some magic Man of Action dust on it. Finally, I'm about to jump into another pass on a feature adaptation of one of my creator-owned books. And that doesn't take into account all the proofing I'm doing on all the various books currently in production ... lettering, coloring, design. My brain's on fire from all this concentratin'!

I’ve followed your career for years, first as a fan and then as a writer about comics. And since the success of Ben 10, I’ve noticed you change the type of assignments and comics you do. Has your success with Man of Action in the animation field changed the way you view comics since (presumably) you’re not under pressure to make your full living off comics?

It's definitely afforded me more freedom of choice and allowed me to shrug off whatever stink of freelancer desperation I might've carried around from the early days of my career. There's still pressure, but it's that good kind of pressure a creative artist can put upon himself, the kind that hopefully makes you better. I'm doing pretty much what I want ... which was always the goal from the very beginning.

And I know I probably take shit online just for putting out that general, "I do what I want" vibe. It comes with the dinner. And then, of course, I give interviews like this one and that seems to piss off someone, somewhere, even more. But, hey, I feel like irritating the occasional internet grouch is part of my job as a full-service comic book creator. If you're not upsetting someone out there in some way, you're clearly doing something wrong in your career.

But be that as it may, you haven’t completely given up on writing comics for others – like Catalyst Comix, which you mentioned earlier. What made that something you wanted to sign up and reinvent someone else’s characters in comics for?

Mainly because, in talking to [Dark Horse Publisher] Mike Richardson about it, he signed off on my approach to the material and I realized I'd have a lot of leeway ... almost as much as I would have on a creator-owned title. That's pretty much my main criteria for taking on work-for-hire comic book gigs these days. It's the same reason I did Haunt with Nathan Fox ... because we were given all the rope we needed to hang ourselves. And the thing is, I'm not afraid to fail. As a creative artist, you have to try things and experiment and push yourself into possibly uncomfortable places. If you don't, you'll never get better. So, for me, if the work conditions are right, and I'm feeling like there's some sort of creative opportunity there in a work-for-hire situation, why wouldn't I go for it? I don't know if I could do it exclusively, but as an adjunct to my creator-owned work, why not?

Do you think doing comics helps you in your animation work?

To be honest, not really. Writing for TV -- especially for a specific demographic -- is really its own thing, containing its own demands.

And vice versa, does animation work help you in the comics you’re doing?

No way. I protect my comic book work, that process of creation, with everything I've got. It's one of the purest things I've ever had the privilege of experiencing in my life, and I definitely don't want one thing infecting the other.

Currently your primary creator-owned work is seemingly two sides of the same coin – Sex and The Bounce. One about leaving the superhero life behind to try to have a normal life, and the other a younger person trying to live up life as a superhero the most he can. After all this time, why does telling these kind of stories through the prism of superhero fiction such a draw to you?

It's an old song for me, but for better or worse, superheroes are just a fundamental part of my DNA. I've read them and loved them for as long as I can remember. I've written a ton of them, from the biggest icons on down ... but at the same time, I'm also a grown man who often finds himself grappling with that relationship in many ways. I find it more and more difficult to escape the fact that these superhero characters were built specifically to entertain children and, somewhere along the line, a few successive generations of dedicated readers -- mine included -- were unwilling to let them go and now there aren't many kids who read currently published comic books, because it's mostly geared for the over 30 crowd. If there were still a legion of bright 12-year-olds out there who were as passionate about reading Marvel/DC superhero comics as I was when I was 12, I'd be more than happy to keep writing them. But it's difficult to imagine writing, say, an X-Men title for a readership that's not much younger than I am ... which means they're way past identifying first-hand with the metaphor that made the X-Men concept so exciting 30 years ago (when it was mainly a teenaged or even pre-teen readership). It seems like that would be a weird audience to write for. Maybe it would be some sort of bizarre challenge, I dunno. And for the guys who're doing it ... hey, more power to 'em.

Ironically, it's the animated Marvel shows that are reaching that original age group that these characters were originally meant to entertain ... kids, 6 to 12. So far, so good. But I wish the actual comic books were still aimed at that age range ... and not like the ones so obviously branded as "kids comics" or, even worse, "all ages," which I'd imagine just drives kids far away. Y'know, when I was 7 years old ... there was Spidey Super-Stories and there was the "real" Amazing Spider-Man comic. Even as a 7-year-old, I knew that one sucked and one didn't. I really don't think much has changed since then, in terms of what really appeals to kids.

I just feel like guys like Stan Lee, John Broome, Jack Kirby, Roy Thomas, Len Wein, Denny O'Neil, Arnold Drake, Gardner Fox, Steve Englehart, Marv Wolfman, Jim Shooter, David Michelinie and many more ... they knew their audience was primarily children or, at best, teenagers. But they never wrote down to them. If anything, they were instrumental in raising the literary perceptions of young readers in a really profound way. They did for me, no doubt about it. Superhero comics don't seem to function in that way anymore, and that bums me out.

Jesus, I went off on a tangent there, didn't I ...?

Tangents ahoy! Like you said, you write that way in your animation work – at Marvel and elsewhere. Forgive me if I’m missing something, but in your creator-owned work have you done something aimed at that ideal 12 year old out there? Or do you think the industry or mechanism that gets comics out there, isn’t built for those kids at all anymore?

I've done one or two creator-owned books that could probably be read by a general audience. But you just said it yourself ... the industry isn't set up to get comic books into the hands of kids in any meaningful way anymore. I'm not in any position -- or have the kind of power -- to do what's necessary to turn the big ship in the direction it needs to go to get the kids back. So, until someone does, I'll be delivering material that hopefully speaks to the readership that exists right now.

Ironically, I think the last generation of bona fide kids that actually bought and read comic books were the first-generation Image Comics readers, pre-teen or young teenagers in the late '80s/early '90s, who got caught up in the excitement of the first Batman movie, were psyched at seeing the new art styles and new publishers and, unfortunately, the speculator boom that came soon after. Now, once the market contracted, a majority of those readers fell away. But that generation of readers -- the ones that stuck around, I mean -- has grown up as I've been working in this business. They're in their 30's now... and I'm writing for them. Mainly at Image Comics. And, clearly, I like the creative freedom of a "mature readers" label, particularly when it comes to stuff I own.

In an interview we did at Newsarama, you said part of the reasoning for doing these was to tell the kinds of superhero stories that the predominant superhero publishers – DC and Marvel – couldn’t and wouldn’t do. I remember you talking here at CBR in 2008 about a great pitch you had at Marvel to do a political-themed superhero series, but I imagine that wasn’t the first or last idea that the Big Two turned down for perhaps being too outside their comfort zone. Of the work you have done for them, what has been the most surprising that you were greenlit to do and be published?

I dunno ... maybe the Dark Reign: Zodiac book I did with Nathan Fox for Marvel, during all their "Dark Reign" nonsense. We were kinda poking fun at the circumstances of the Marvel Universe in an actual Marvel comic, exposing its narrative contradictions -- and maybe some of its ridiculousness -- which I thought was a mildly subversive act at the time. Not to mention, I'm sure Nathan's art was a shock to the system of the average Marvel reader.

Turning it around – is there a pitch you had out there that you’ve had the most hopes on that it’ll get the greenlight but wasn’t approved? I know you’ve done several, on your own and as a group – but what is the biggest missed opportunity in your mind for work-for-hire projects you’ve dreamed up?

Ah, I dunno ... things that didn't work out, in hindsight, it's always for the best that they didn't. I thought my Justice League Academy idea was a commercial slam dunk, so much so that I'm actually surprised they didn't just rip it off and do it without me involved. But in the long run, why do I give a fuck whether or not I deliver a commercial hit for DC Comics? What does that get me, ultimately? Or, on the other hand, four or five years ago I pitched a Teen Brigade series to Marvel that had the exact roster of characters that I ended up using in the 2011 Vengeance miniseries ... including the two I created: Ultimate Nullifier and Miss America Chavez, who people seem so excited about now in Young Avengers. So I got to see that particular idea through and get it in print, which was cool. Sometimes you just have to be patient with these things. A good idea can always come back around.

Another thing I noticed while looking over your bibliography for this interview is your uncanny luck/talent to work with an inordinate number of top comics artists before their famous – Sean Phillips on Wildcats, Eric Canete on Ladytron, Chris Burnham on Nixon’s Pals, Jose Ladronn on Cable and Ed McGuinness on Mister Majestic, to name a few. Looking back on the number of artists who’ve grown to be big forces in comics after you worked with them, what would you chalk that up to? You being an early pinpointer of great artists, or what?

Well, with someone like Ladronn, I just lucked out there. He had the Cable gig before I did. And Sean Phillips had a pretty healthy career in British comics and as a Vertigo artist long before I dragged him over to Wildstorm. But, beyond that, I don't think it's too egotistical for me to say that I have impeccable taste in comic book artists. If someone doesn't agree, then obviously they have no taste. It's a great pleasure for me to work with guys I'm a fan of. I mean, look at the Catalyst Comix line-up: Dan McDaid, Paul Maybury, Ulises Farinas ... these are killer talents that Marvel and DC would never dare hire for their mainline superhero series. And that's their loss, completely.

The thing is, I always want the comic books I make to be great. And just because a writer works with a so-called "A-list" artist doesn't guarantee that the work itself will be great, no matter how talented that artist is. It also doesn't guarantee that the work will sell in great numbers either, but that's beside the point. I'm always on the lookout for that certain kind of alchemy that occurs with a good writer/artist collaboration. For me, that's where greatness can spring from.

I dunno. Maybe. I generally know what kind of artist I want to work with, I usually have someone in mind during preliminary discussions with an editor or a publisher. Otherwise, I probably wouldn't be having the discussion in the first place. My own career history has shown that, many times when I've been paired up with an artist that I didn't know or suggested myself, I haven't turned out my best work. I don't know how I compare to anyone else working in the industry, but I didn't grow up loving comic books to just write them -- just to be one, isolated part of the typical assembly line. As a young kid, coming up with my own horrible, hand-drawn comics, I wrote them, drew them, lettered them, colored them, designed and drew the logos, even drew in the price captions, company mastheads and UPC boxes on the covers. I wanted to "make comics" ... which, for me, means being involved in every aspect of their production. That probably makes me a big pain in the ass to some people, and I'm sure on some level they're right. But, y'know, I gotta be me.

What about comics that excite you – what books or creators are you excited about today in comics, and where do you find out about them?

I try to keep my ear to the ground as much as possible. In a world full of endless white noise, that's the only way to find the good stuff. I find it hilarious when I read interviews with other creators and, when asked about what they're currently reading, they either rattle off a few of the typical, top ten Big Two sellers or they cite series written by their industry friends (who coincidentally happen to be working at the same publisher they are). To me, it's lame and it's transparent. When guys like Alan Moore or Mike Baron would get interviewed back in the day and name check books like Yummy Fur, Cerebus, Mister X, Journey, Love and Rockets or some other really obscure independent comics they were reading and enjoying ... these were things they seemed to be genuinely fans of, as opposed to just trying to kiss someone's ass in an interview setting.

So, having spouted all that ape shit, right now I'm really digging Michel Fiffe's work on Zegas and Copra. I thought his Deathzone one-shot was the best DC Comic I read last year ... and it wasn't even published by DC. I like Benjamin Marra's comics a lot. Paul Pope's stuff is almost always cool. I love what Charles Burns does. Jim Rugg's Supermag! is gonna be very cool. And I still go back and re-examine comic books I grew up on, as though I were some sort of funky archeologist trying to discover new meaning in these old artifacts. I also like to dive into the oeuvres of guys like Don McGregor or Steranko or Chaykin or Kirby's '70s Marvel work or Crumb's autobiographical strips and try to pick 'em apart, like I'm doing research for some sort of in-depth comic book dissertation. There's still a lot to learn about the medium, and that definitely excites me.

And your habits as a comics reader – have they changed much over the course of you being a comics creator? Do you still go to your favorite shop and read them the way you do, or has that changed?

It's changed, but I think for the better. I still try to hit a comic shop every week, but I guess I'm a lot less tolerant of books that might be perfectly acceptable as base-level genre entertainment, but if I'm going to spend time as a reader -- as opposed to spending time as a creator -- what I'm reading has to be goddamn spectacular. It's got to blow me away. Life's too short, y'know? And I guess I've been around too long, read too much, and seen behind the curtain enough times to get very excited about someone's "revolutionary" take on Iron Man or Animal Man or whatever Marvel/DC IP is getting a spit and polish this month. It's all very "been there, done that" for me. That's not an insult to the work, because fundamentally it's not aimed at me anyway (although, as I said before, I suspect it's still aimed at my age group). But, as it happens, I think there are more readers out there like me than anyone wants to admit. And I also know that the Big Two publishers aren't going to take a chance at something genuinely revolutionary with their IPs ... not when all that popcorn is at stake.