Writer Jamie S. Rich has been a staple of the independent comics scene for more than 20 years, first as a frequent writer to letters columns (sometimes called a letter hack), and then as an editor at Dark Horse and Oni Press. Since 2004 he's made his living as a freelancer, creating comics like It Girl & The Atomics and You Have Killed Me, and writing about film for several Portland, Oregon, newspapers.

But that's not why I reached out to interview him. Yes, we talked about his comics work, but what I was most interested in is his recent prose novella Bobby Pins & Mary Janes, a story about a young woman trying to carve out a life while working as a comics editor. Although far from a comic industry tell-all, it's unique for providing an honest perspective on the editorial role in comics while also serving as a convincing slice-of-life story.

We also discuss his recently announced webcomic at OniPress.com called A Boy And A Girl, his penchant for collaborating with artists in person, living in the comics hub of Portland, and his recent endeavor to do a writer's version of off-hand sketches for fans.

Chris Arrant: Thanks for doing this, Jamie. What are you working on today?

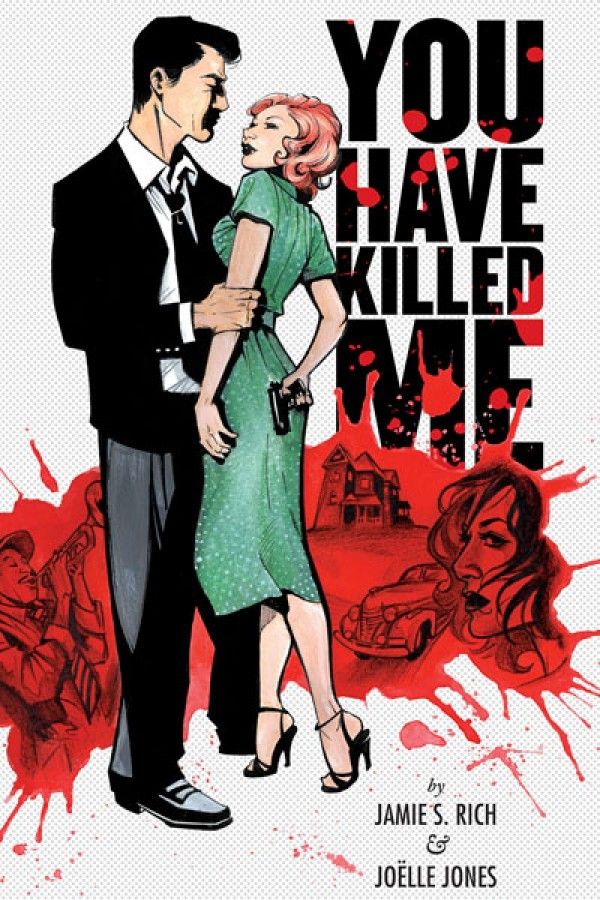

Jamie S. Rich: I have an unannounced project with Megan Levens, a traditional romantic adventure in a real classic Hollywood vein, that we recently had greenlit. And by recently, I mean in the last two weeks. It’s one of two comics I have under way with Megan; the other is in an earlier stage, still being pitched. I met her years ago, I guess around 2004, the last time I went to the Savannah College of Art and Design as an editor for Oni Press. She was graduating, and I vaguely remember her portfolio review. I apparently told her that she would have no problem working in comics, so it behooves me to put my money where my mouth is. Maybe she made that up, though. If so, it’s a great ploy. I met her again in 2009 at Comic-Con when I was promoting You Have Killed Me, just to show you how sometimes the gears can grind slow. We did a short story for Mike Norton and Tim Seeley’s Double Feature digital comic first, and now we have multiple things going, both very different.

So, I have been writing that. I also spent much of the morning reminding people that the third issue of It Girl & The Atomics just landed in stores. And I’ve been polishing my review of the Lon Chaney movie The Penalty.

How much does promoting and marketing your work play into your overall workload as a freelance author?

Quite a bit. Particularly when you’re talking about creator-owned work, your personal investment is quite large, and so it behooves you to get out and pound on doors. In this day and age, readers and retailers alike like it when they can deal directly with the people making the books, too. You have to be your own engine. I try to manage my days so that kind of stuff gets done in the morning, while I am having my coffee, answering my e-mails, reading my RSS feed, etc. I try to turn off the internet somewhere mid-day and get on the keyboard for actual work.

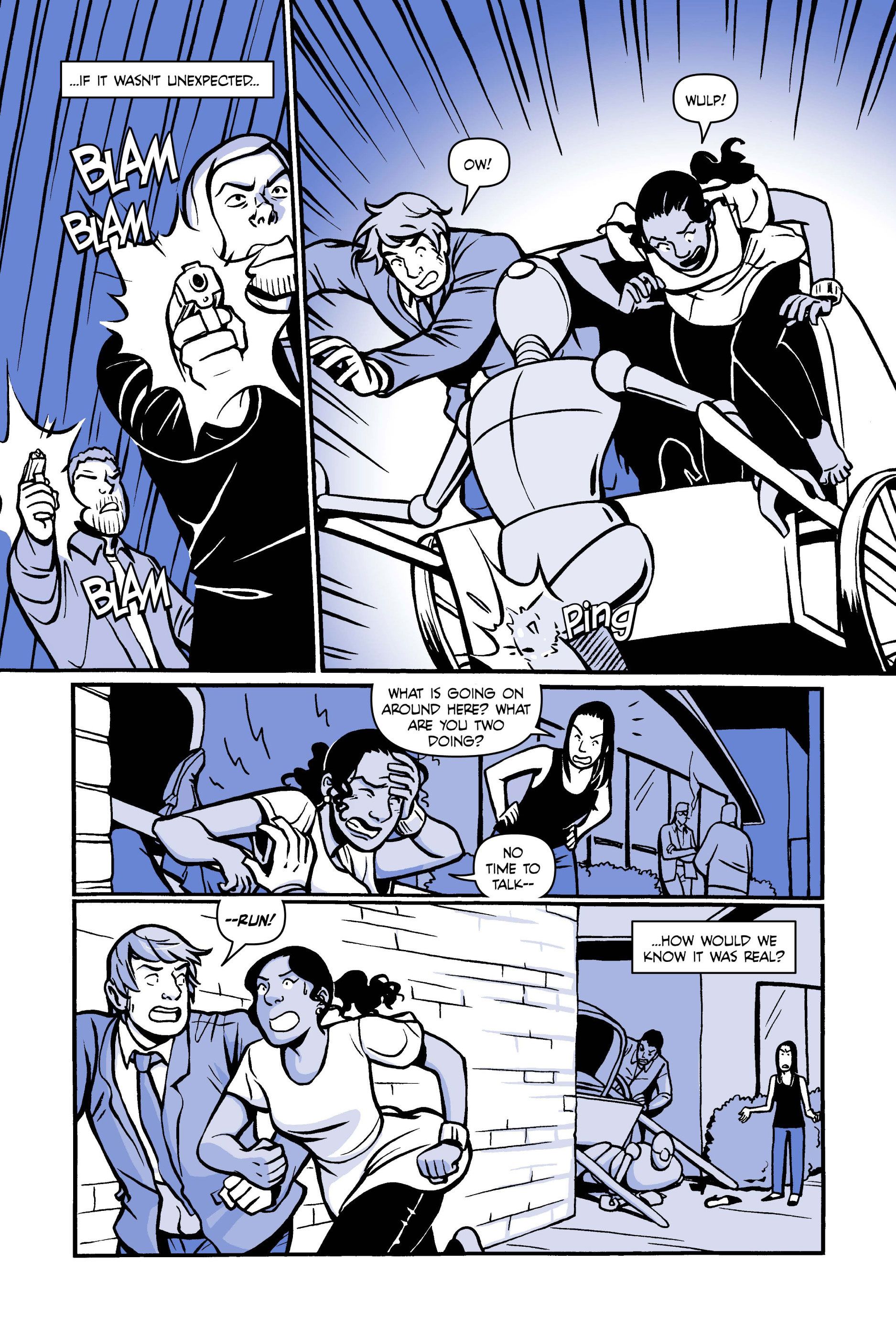

In terms of new work, the big announcement for you in the past few weeks is that your comic with Natalie Nourigat, A Boy And A Girl, is now positioned to be one of the launch titles in Oni Press’ upcoming webcomics initiative. You’ve called this a “futuristic romance,” so what’s it about?

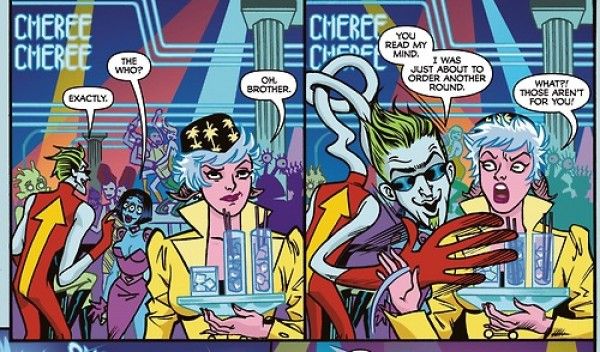

It’s about two people who meet by chance and their attempt to act on their feelings while they have the ability. A Boy And A Girl has a kind “date night” structure, in that it mostly takes place over one night. Charley, our female protagonist, is leaving in the morning to participate in a work program, and so it’s almost like she’s a soldier shipping out, she needs to enjoy herself before her whole life changes. Travis, of course, doesn’t want her to go, it’s not enough time. As the night wears on, their feelings deepen, they explore the city, and circumstances go pear-shaped as some gangsters Travis has pissed off chase him down. I like playing with such a limited time frame, of having a plot that escalates while the clock ticks. It also allowed Natalie and I to toss ideas back and forth and build the situations based on what parts of our future world we wanted to explore. There are robots everywhere and night clubs on top of skyscrapers, and a whole new social dynamic based on technological advances and the like.

What came first, the romance or the futuristic setting?

The setting came second. We began a vague notion of wanting to do something that was personal and relationship-based with two strong characters. We batted around a couple of options and basically were just looking for interesting things for the characters to do and be, and a reason for them to come together. How we landed in the future is something I don’t really remember anymore. It kind of just evolved, and one day we knew we had found the right thing. Some bad ideas finally led to a good. Once we established the relationship between Travis and Charley, what made them attractive to one another, that was the first step to the rest of it making sense. It wasn’t an arbitrary decision, either. What is going on in their world in their time is important to what is happening in their lives. It couldn’t be set in the present as we know it.

Back at San Diego this year, A Boy And A Girl was originally announced as what I thought would be a physical book. How’d it transition to being a webcomic, and is a physical edition of the series still in the plans?

It actually has always been a webcomic, Oni Press just teased the information out slowly. I have been aware of their plans for a while, and I actually signed on first for the comic I am doing with Dan Christensen, a kind of supernatural crime comic, what I’ve joked is the David Lynch remake of You Have Killed Me. I was enjoying the format, and so when the opportunity came up to pitch a book with Natalie, I suggested we take the same route. It actually really worked in our favor, because the chapter structure lent itself to playing with point of view. The sections alternate between the boy and the girl; I think it starts out that he narrates the even numbered chapters and she narrates the odd, and then things cross over as they come together. There’s a definite “he said/she said” aspect to it, though I guess it’s more “he thinks/she thinks.”

My understanding is that there is an end game to publish the material in book form, too.

You’re doing A Boy And A Girl with artist Natalie Nourigat, who happens to live in Portland like you. I’ve noticed that by coincidence or circumstance you tend to work with artists whom you can collaborate with in person like Nourigat and Joëlle Jones. In comics that’s relatively rare, with most writers and artists not often even meeting in person before collaborating. First off, is it coincidence or is it something you prefer?

It’s a bit of both. I really like being able to meet over drinks and talk about what we’re doing, and it’s natural that living in the same town with so many comics people, we’d end up collaborating. At the same time, Megan lives in Los Angeles, and both Dan Christensen and Nicolas Hitori de are in France -- though Dan is an ex-pat, he’s an American transplant. So I really go half and half. Communication is important in general, we all talk all the time in some capacity and share the work as it’s being completed. I find collaboration essential to comics. The It Girl & The Atomics team is all over the place, everyone lives in a different area, but it doesn’t prevent us from having a real camaraderie on that book, too.

Some people I know are strictly into email correspondence, while others working with people they don’t know face-to-face use email, phone and video chat. How do you generally communicate with your collaborators, especially ones like Dan and Nicolas you can’t ring up to go out for a drink?

E-mail exclusively so far, at least for the guys overseas. I am not a big fan of the phone. I always feel like I am put on the spot when someone calls. I actually prefer it when my editors e-mail, for instance, with suggestions or something that requires a creative decision, because it gives me time to react in private and sort out my thoughts, particularly if it’s something I disagree with. I don’t know why, but on the phone I tend to be less tactful and blurt out my immediate response.

What is it like being able to meet with collaborators in person and going over things as opposed to online or phone correspondence?

There is a tactile element to it, a more direct ability to problem solve by sitting together and holding the material in your hands, and sorting stuff out together. For instance, the next project Joëlle and I are doing together, we’re co-writing from an idea she came up with, and so there’s a lot of back and forth. Meeting up at our local and going over thumbnails, we can spark off one another and get new ideas and also have a genuine dialogue about what is happening. It’s more immediate, I guess. Most everyone else, we do e-mail, but there is the delay between sending the mail and getting an answer. With the two dudes in France, you’ve got international time zones between you. The collaboration can be just as involved, but it’s a long distance relationship.

Every project is a little different, too. Megan and I are in touch nearly daily, and I send her each section of script as I finish it, whereas Natalie was looking at the script for A Boy And A Girl more on a weekly basis. I wrote the second book for what I am doing with Dan over the summer, and after the initial pages, he opted to wait until I was done to read them all at once. Joëlle did the same on You Have Killed Me, she wanted to see how the back half played once it was all done.

The one thing maybe that we benefit from hanging out, though, is just the spontaneity of being out and about and somebody saying, “Hey, what if ...” You know, Joëlle telling me her idea while we were waiting for a movie to start, or Natalie suggesting a theme she’d like to tackle if we do another book while we’re grabbing some food. It kind of happens more organically that way. We can also get together on the spur of the moment to celebrate a job well done or blow off steam.

This speaks to the broader issue of Portland becoming a hive of comics creators. You’ve lived in the area for a number of years, so what is the big draw do you think?

It’s a fairly common question. I think the fundamental reason that comics people started coming here is all the publishers. Dark Horse started it. Then Top Shelf and Oni Press came along, and people would visit and decide to stay. The city itself is very artistically oriented. The populace takes a kindly view to artists of all stripes, and I think there is a general acceptance that the guy serving you coffee is a poet, the clerk at the music store is in a band, etc.

For comics in particular, given the amount of time it takes to draw a graphic novel, and the solitary nature of the work--something that is only really comparable to writing prose novels--the fact that it rains the vast majority of the year means it’s real easy to stay indoors and do your work.

How has the influx of comic creators in the Portland area changed the social scene, and the industry scene?

There are way too many release parties to go to anymore. “Oh, good, another PDX peep is having a new comic out, here we go!” It’s easy to get jaded!

In general, I think it’s like any other scene in that we all have our own cliques. I tend to hang out with certain people on a regular basis, and that group may expand or contract depending on what else is going on, but it’s not like we are so localized that we’re always ending up in the same place. It’s the random surprises anymore, like getting to sit across from Vera Brosgol at George Rohac’s going-away brunch--I hadn’t seen Vera in ages so it was fun catching up.

What the numbers have really done for us is get us more noticed by the city at large. We had the Mayor declare an annual comic book month that happens around the Stumptown Comics Fest, the Portland opera has been inviting artists to their rehearsals to sketch and blog about what they see, that kind of thing. The geek subculture in general has just really taken off. There is a whole website, run by a woman named Kenna Conklin, devoted to tracking everything that is going on around the city.

Taking a couple steps back, I wanted to ask about your long-term collaboration with Joëlle Jones. Comics seem to be defined by epic pairings like Kirby & Lee, Claremont & Byrne, Morrison & Quitely, Palmiotti & Conner. So what’s it like working so closely and repeatedly with one person?

Well, that’s pretty impressive company to be considered alongside. I tend to think of us more as Bob and Doug McKenzie.

The answer is simple: She’s just awesome. I love working with Joëlle and cherish every project. Your best collaborator is going to be the person you’re most eager to impress and most frightened to disappoint, because their work is so good, you just want to be able to measure up. Joëlle is remarkably talented and endlessly creative and it makes me have to be better.

The reason the collaboration works is we’re generally on the same page about things. We usually want to go in the same direction, we laugh at the same things, and so the communication is easy. More often than not, when she draws something based on my scripts, it’s exactly like I saw it in my head; when it’s not, it’s usually better than what I imagined. At the same time, the chemistry that is created when we work together, I’d like to think neither of us can do what we do as a team with anyone else. We build the Eiffel Tower out of metal and brawn.

She’s also kind of a rotten person, so she needs someone who can put up with her. Or that might be the wrong way around. That might be me. I am forgetting.

You compare yourselves (jokingly?) to Bob and Doug McKenzie from SCTV, brothers. Brothers, which is deeper than mere collaborators – do you have some sort of brotherhood/sisterhood connection with Jones?

You could say that. We’re best friends when it comes down to it. Even if we stopped working together, we’d still hang out just as much and be pals. And pet sit for one another. The value of a good pet sitter is not to be underestimated.

You recently hosted a screening of the film The Big Sleep in a local Portland theater tied into your crime noir graphic novel You Have Killed Me. To us you’re known as a comics writer, but you’re also a prolific movie reviewer – so what was it like to host this “Evening with Jamie S. Rich”?

It was kind of surreal. Tom Shimmin and Amber LaPraim from Oni Press put it together, and I think originally it was supposed to feature more contributors than just me, so it was really bizarre to have so much attention paid to my having picked a movie. Tom hosted the Q&A beforehand and I did my best to sound like I knew what I was talking about. I think it went pretty well. I’d love to be able to pick movies and show them like that all the time, to curate my own festival. Maybe I should try to do it online sometime, like do a virtual festival that people can participate with at home. I’ll tell everyone what movies and when I am watching them, and I don’t know, tweet or something.

The genesis of this interview came from me wanting to talk with you about your recent serialized novel Bobby Pins & Mary Janes, a fictional story of a woman working in the comic industry. It’s not an expose by any length, but seeing the comics industry talked about from the inside so frankly is pretty intriguing for me as a fan and someone covering the industry. How’d this idea come about?

I think Parker still says in the novel something about how she wish she’d kept a diary when she started working for the publisher, and that was something I used to joke about back in my Dark Horse days. Had I kept notes about the day-to-day craziness, I’d have left four years later with a novel.

The book itself basically began with the image that starts it, with the bobby pins on the floor, and this character who scatters these things that she needs to basically keep herself together willy nilly, where she can always find them. It was born in a hotel room at Comic Con when a friend was explaining why she always had bobby pins on her floor, and that whole opening paragraph appeared in my brain fully written. How the rest of it came about is as mysterious to myself at this point as it is to you: it just kind of happened. It sounds cheesy when writers say this, but it’s true: sometimes characters arrive and tell you who they are and you just try to write it down accurately. In this case, it was a whole new challenge of writing from a woman’s point of view, and the comics thing might have just come out of trying to find an interesting job for her to do and also the notion at the time that comics were invading mainstream publishing, and so that might actually make the book commercially viable. Thematically, I wanted to sort of tear apart things I had done before and critique my male characters and basically in a lot of ways eviscerate my own persona and write cruel parodies of myself, so that went into that, too.

Did you ever think that setting it inside the comic industry was too “inside baseball” so to speak?

No, because fiction is supposed to be about things that are different from the reader. I mean, I don’t have any books on my shelf that detail the experiences of a comic book writer, so if I can understand all of these novels that detail lives that are different than my own, and jobs that I’ve never worked, than there is no reason other people can’t identify with a character who works in comic book publishing. We compared it to The Devil Wears Prada, which is a workplace story that is just as specialized as comics, and probably even more fantastic seeming to an outsider, and that was a big hit. I think it’s only people who are inside an industry like this who get hung up on those details. It’s a very adolescent way of thinking. “I am so special and unique, no one can possibly know how I feel. *sob*”

That said, it’s also my challenge as a writer in any given situation to give you the information you need to understand whatever it is I am presenting. It’s all about relating an experience and creating a vivid picture of who and what and where. It reminds me of when people would say they avoided reading Blue Monday because the first story arc was about Adam Ant and they never liked Adam Ant. Okay, fine, but haven’t you ever been obsessed with a band or an actor or a comic book character? Is not the experience then relatable, and the obsession interchangeable? No one ever says, “I don’t read Superman because I’ve never been an alien from another planet and probably can’t identify.” Only 44 people in history can enjoy the TV show The West Wing because they’re the only ones who have ever been President of the United States!

In short, my fear wasn’t that the story would be inherently inaccessible to outsiders so much as I would fail to tell it properly--which, knowing me, I probably did.

I beg to defer in that regard – but how did you check yourself as writer to make sure you’re taking the reader into the comics publishing world without being too explanatory?

That’s a difficult balance. You don’t want to explain everything, you have to toss in jargon and references naturally so that your people seem real. If there is some kind of story excuse for it, someone needing to explain what is happening to someone else, then that is always useful, to work the exposition into dialogue. One of my favorite TV shows of all time is ER and they were pretty good about that. The shows would move fast and they would toss out medical terms and just leave them there, if you didn’t know what they meant, that was fine, because you were in the moment as a viewer and the writers had your trust. So I aim for that kind of balance, and think about, “If the readers don’t know what this means, can they still understand the scene?” If not, it’s time to start explaining things.

Have you had any conversations about the topic of the book with other creators spurred by this inside look at the industry? If so, can you talk about that?

I haven’t actually talked to anyone specifically about the book, except for a couple of peers who thought they recognized certain things (and were mostly wrong). Some of what is in the book is definitely taken from experience, and some anecdotes are stories I’ve heard. I pull various Oliver Stone moves, making composites of different real figures and combining details from multiple events. But during the writing, I kept it to myself. Comics is a gossipy business, and I didn’t want any speculation or whispers about what I was doing.

Speaking of prose writing, you recently opened yourself up to doing commissions short stories – like a writer equivalent of a convention sketch for an artist. What spurred this on?

Money. Trying to find a way to make the occasional side cash. Most writers envy how artists can sell original art from the books or do sketches, so I was really trying to commodify my own work in a different way. Anais Nin used to do private stories for collectors, so there is some literary precedent.

How has it been so far, in dealing with this as a transaction, and in the results?

It’s been all right. The people who have participated have seemed to like how their commissions came out. I think overall, folks are fairly baffled by the concept or just don’t quite see the why of it. I enjoy doing them, it’s a nice exercise, coming up with a quick story that fits one page. They tend to be a little more poetic and simple than what I am used to and that makes for a nice break. I do similar writing exercises for myself sometimes, give myself a challenge and then set out to write some manner of complete piece within an hour and post it to my blog. Just to get the wheels turning.

This idea of commodifying your work and using it as a writing exercise – how do you think it limbers you up so to speak for your main work ... and would you recommend it for other creative types?

The limbering up comes from just writing fast and not pushing too hard, just letting the words happen regardless of quality. Obviously, that’s different when writing one of the actual commissions, because that does have to be good and it has to fit on one page, so I’ll do more polishing. But it starts with the same principle. I have people give me a picture or a word a phrase to begin with, and I go with whatever comes to mind based on that. For my own warm-ups, I either find the starting point myself, or sometimes I toss out a request on Twitter and take whatever suggestion comes back.

Basically, it’s kind of like stretching before running, you start the flow on something other than your main task, and you get the kinks out before you hit the road. Joëlle does it with her art, she does “daily doodles” and gives herself an hour to draw something. I stole the idea from her. What’s funny, is every time she does it, someone takes issue with the fact that she calls them doodles because they look like finished, accomplished pieces. But that’s just because she’s in shape. Writing and art are just like any other activity or work: the more you do it, the better you get.

At least at the act of doing it. Quality of content is a whole other thing!