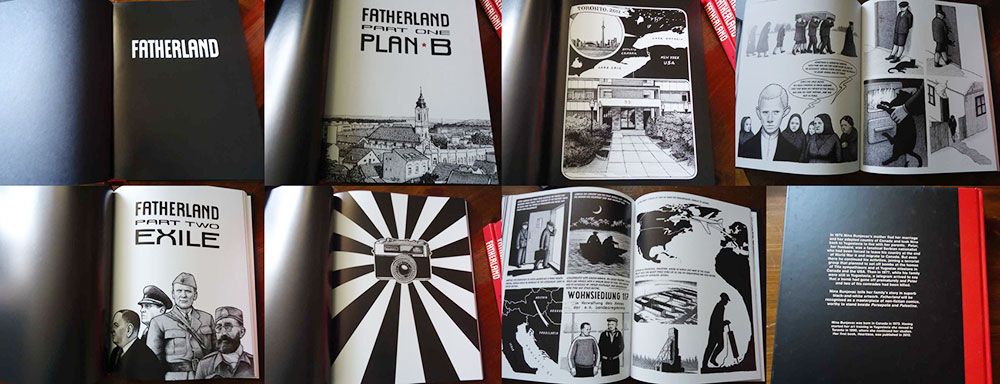

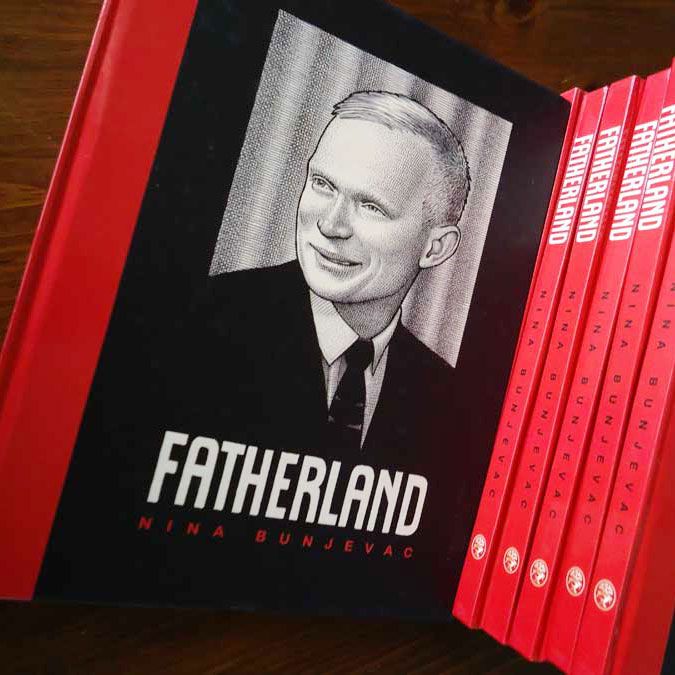

Fatherland: A Family History is a gorgeously drawn, black and white, biographical comic book (or graphic novel, whatever you prefer) by Nina Bunjevac. Ever since I first saw it I have been very excited to share it with you. The quality and quiet intensity of this book makes it a must-read for anyone interested in the ways the medium can subtly convey a depth of emotion without excess dialogue or narration. It is a harmonious, elegantly solid portrayal of a jumbled collection of terrible events, and for me it was a great step forward in my own expectations of what it is possible for a comic book to convey.

In the simplest terms this is a book about Bunjevac's childhood move to Yugoslavia with her mother and sister, and about her violent father who’s activities as a Serbian National terrorist drove them away. Almost as a side act, the book offers a broad history of twentieth century Balkans, as it impacted her family and their lives… But this is the most basic description of the book, in many other ways it is a stark indictment of the way choices made by the powerful impact the people under their care, and while there are no judgements or accusations from the author, the pain of her family is laid bare for the reader to see.

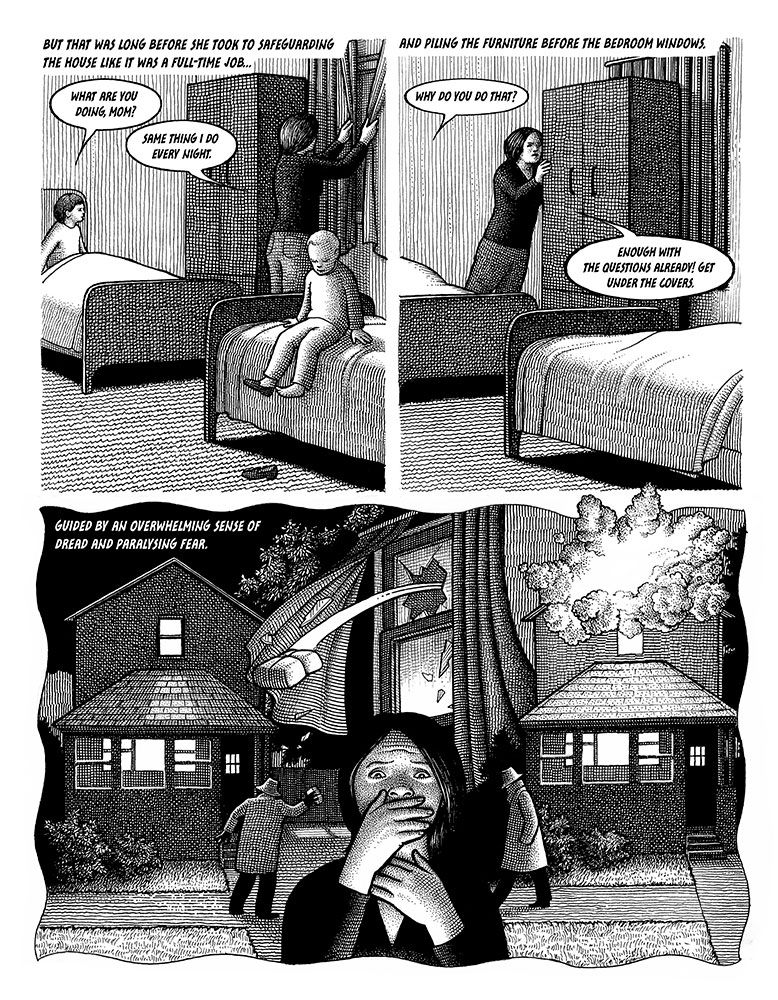

Beginning with the author in present day Canada, we see her interact with her aging mother who is not a little paranoid and still trying to feed and care for her adult daughter. We’re quickly swept into a series of flashbacks, depicting Bunjevac's childhood in Canada and the events which led her mother to flee to Yugoslavia, forced to leave her son behind with a controlling, abusive father who is risking all their lives. As the story shifts further back to the events which led her father to choose this path, so too the narrative style shifts and Bunjevac delicately places all of the pieces on the board for us to see the painful inevitability of this life. From his own abusive father’s death in the concentration camps, through to his childhood experiments with torture, we understand the pain and anger which created him.

The consistent pain and loss associated with a life led without warmth or care are particularly apparent in this second half of the book about her father and his history. Though understanding the pain which brought this man into being does not mitigate or detract from the choices he made, it does make his focus on destruction seem inevitable, and within the context of his view of reality it almost is a redemption as he turns his naturally destructive tendencies towards a cause. Throughout the story the thin thread of fear and selective amnesia which her mother clings to is tugged at, she seems to represent Bunjevac’s strongest external tie to her past. By unravelling the past it is as if the author is trying to unravel her mother’s behavior, seeking simple explanations and finding instead this chaotic confluence of poor choices and bad luck which led them to the people they are today.

Llike Spiegelman’s Maus or Sacco’s Palestine, there is much here to digest, both on a personal level and a wider, political level. By using a repetitive narrative structure the intimate story of a nuclear family is placed in the wider context of grandparents and great-grandparents, then into the much broader context of world politics and the ramifications of decisions made far away. Using an overarching narrative could easily have lead to a personally accusatory tone, but Bunjevac is content to weave her story and allow us to come to our own conclusions. By telling the story twice, (once from the immediate point of view of the author as a child cataloguing a series of strange memories, and then again from a historical perspective), the poor decisions made by adults begin to make sense in the context in which they were made. By first giving us the stream-of-consciousness tale of the traumatic changes in her little girl life and following it with an examination of the causative events leading up to those changes, Bunjevac creates a richly patterned story which draws us deeper in to the broadly political history in a very personal, human way.

Initially Bunjevac’s art attracted me to the book, her labor-intensive technique of using pointillism and cross-hatching everywhere is very beautiful, creating a strangely conflicted reality where everything and everyone seems incredibly solid, yet simultaneously as if they’re woven from a delicately woven fabric which could tear apart at any moment. The subject matter is weighty and yet incredibly tenuous, both the people and the world-altering events which are depicted, and the art is a perfect metaphor for this dichotomy. The metaphorical jail she finds herself in is constantly reasserted by the complex art, detailed with a million lines of wear and shadow. As an adult and as a child, Bunjevac’s gaze is compassionate but unflinching. She is aware of her family’s flaws and yet she doesn’t label them as such, merely notes that this is who they are and how they came to be this way. All emotional responses, be they love, hope, sadness, shame, or recriminations must come from the reader and we draw what conclusions we will, based upon the information we’re given. By telling her story in this simple way Bunjevac gives us a gift, a freedom to read and understand what happened and how it impacted one small family in many terrible ways.

...

Nina Bunjevac's Fatherland: A Family History is published by Liveright Publishing and out now.