The problem with doing these in alphabetical order is occasionally you get two things in a row written by the same person. Luckily, it's been a while since I wrote about Enigma, and I threw the old one about 300 in between, so it doesn'tfeel like I'm slurping Peter Milligan. But when the man writes good comics, the man writesgood comics! (And, of course, there are SPOILERS below!)

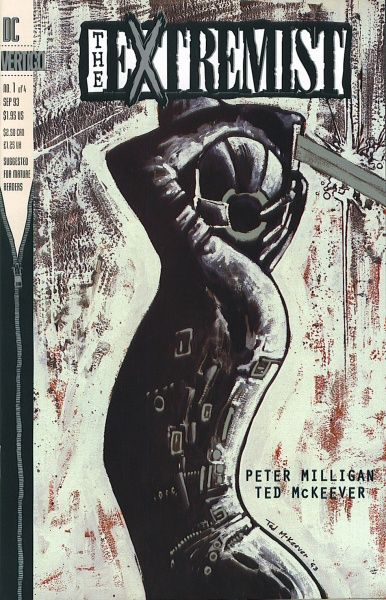

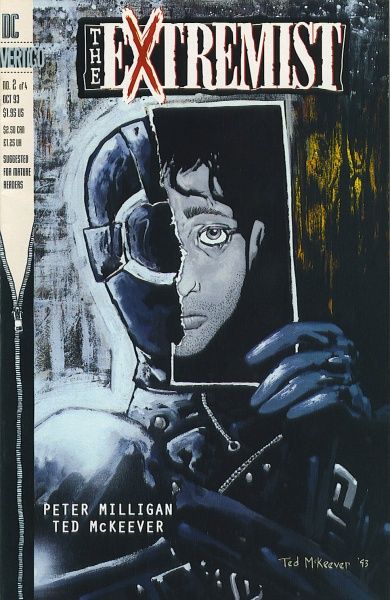

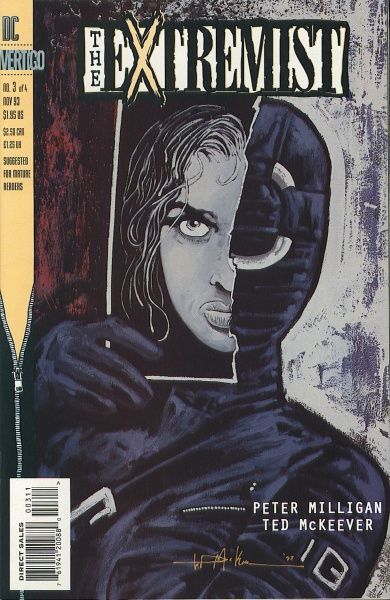

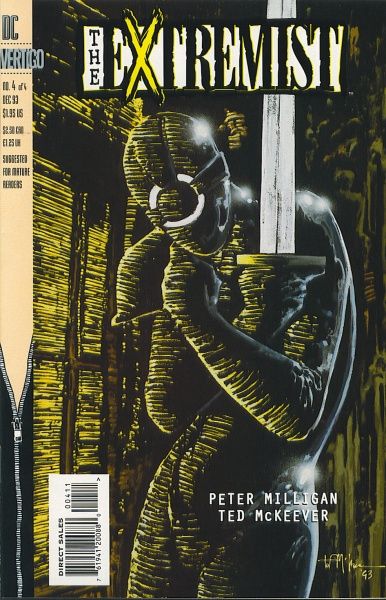

The Extremist by Peter Milligan (writer) and Ted McKeever (artist).

DC/Vertigo, 4 issues (#1-4), cover dated September-December 1993.

Around the time he was finishingEnigma, Peter Milligan was also bringing us this twisted little tale. It's not as grand in scope as that book, but it's a worthy companion piece. Both books are concerned with secrets and sex and how the two often get mixed together. In many ways, this is a much bleaker comic than Enigma. But all is not what it seems in Milligan's world, as usual, and The Extremist has some very interesting things to say.

The actual plot of the comic is pretty standard fare, as Milligan concocts a mysterious group called the Order that uses an assassin to enforce their rule. The Order is running things in and around San Francisco, where the story takes place, and sometimes people get out of line. The assassin is the Extremist, who wears that leather outfit on the covers and carries a sword to dispatch the victims. In the first issue, a woman named Judy is wearing the suit, and we learn that she's playing the role of the Extremist to find out who killed her husband, Jack, the original Extremist. As the story unfolds, we learn about Jack's secret life before his death and Judy's journey into his dark world and her own, and in the end, Judy must choose what kind of life she's going to have. As a plot, it's relatively mundane. We never actually find out what the Order is or who its members are, but they're pretty much a MacGuffin anyway. There's not really an external conflict for either Jack or Judy to handle, as the Extremist's reputation around town means that he/she gets to do whatever she/he wants. So if you're looking for something with a big meaty plot to sink your teeth into, go elsewhere. This is not the comic for you.

But it's so much more than that. I've mentioned many times how obsessed Milligan is with identity, especially sexual identity, and this might be his most disturbing treatise on the subject. Whereas Enigma was about a sexual awakening of one kind, this is about one that is far more malevolent. We can look at it as another iteration of"what happens to someone when the put on a costume?" and it wouldn't be wrong to view it that way, as Milligan shows two people descend into depths they didn't believe existed. Even before this book came out, it was a cliche to suggest that people who were superhero costumes were engaging in fetishistic behavior, but Milligan does something interesting with that theme: he challenges us to think that the sort of behavior people get up to while wearing the costume is desirable. Usually, writers bring up the idea that wearing a superhero costume (the Extremist's leather costumeis fetish gear, sure, but it's also superhero gear) is somehow liberating but depraved, and ultimately to be avoided. Even Alan Moore hints at this in Watchmen, perhaps the ultimate statement on the subject. Milligan asks us to embrace the depravity and consider what it really means, and that makes The Extremist a very uncomfortable comic to read. It's also what makes it so gripping.

The two main characters, Jack and JudyTanner, both become the Extremist. How Milligan sets up his tale is interesting, because we begin with Judy taking up the mantle of assassin in order to find her husband's killer. Immediately Judy feels as if the leather outfit of the Extremist is her "real self," and this disturbs yet thrills her. As she moves through San Francisco's sexual underworld with her handler, Patrick, she becomes more comfortable with the perversion she sees around her. Both she and her husband, Jack, whom we see in a flashback, find themselves drawn to the world of sexual "freedom," but neither can admit it fully. Jack, who is hiding his double life from Judy, wants to tell her about it, but can't. As Judy discovers more and more secrets about Jack and then Patrick, she has to decide if she wants to make the same choice Jack did, which is quit. Jack was killed because he wanted to leave the Order. Milligan asks us to consider whether it was the correct choice. Did he save his soul because he couldn't commit fully to the Extremist? At first, it appears that's exactly what Milligan is saying. But we can't be sure, because as Judy makes her own journey, she finds herself enjoying it more and more. Patrick is a better lover than Jack is, and her old existence seems shallow and pale compared to what she lives as the Extremist. However, she is still makinga journey. Patrick reveals that he killed Jack, and Judy must decide if that was a liberating thing or not. We discover that after everything Patrick did to destroy her life, she joins him in the end and embraces the Extremist. Why? Because, as she tells the last victim in the book, "He'd given me another life." Milligan toys with us, because we expect Judy to "come back" from the extreme, but she doesn't.

It's interesting to contrast Judy's choice with Jack's. Early on in his career as the Extremist, Patrick tells Jack he has to leave her. "She is like the shadow of a tumor across your immortal soul," he tells Jack. Jack refuses, and it's his "morality" that destroys him. He has made a journey into the heart of darkness, so to speak, but he pulls himself out. He does this, ironically, for his wife. Milligan allows us to believe that Judy would not hesitate if she was told to leave Jack. She doesn't have to make that choice, of course, because Jack is dead, but it's interesting that she refuses to avenge her husband's death when she finds out who really killed him. She threatens to, but she comes to realize that Patrick freed her. But did he really?

The freedom from morality that Patrick offers is a double-edged sword, and Milligan does a nice job dealing with this problem. On the one hand, Judy embraces her new life and goes off with Patrick, a new woman. On the other hand, the fourth major character - Tony Murphy, who discovers Judy's diary tapes and becomes mesmerized by the Extremist - is unable to break free of his life. Tony and his wife, especially, are fascinating characters. Tony sits on the steps of Jack's "Extremist" apartment and gets to know him, but Judy ignores him. When Judy disappears, Tony goes into the apartment and finds the tapes and the costume. He becomes obsessed with the Extremist, but he is inept at breaking free from the morality of his life. Janet, his wife, unnerved by his obsession, scolds him and tells him to give it up. She is the voice of reason in the entire book, getting angry at him for listening to Judy's tapes and telling him to get back in the real world. At one point Tony, who's a large man, tries the costume on and looks, frankly, ridiculous (which he acknowledges). Janet catches him and says she's going to her sister's place. "Don't bother getting in touch until you get your sanity back," she tells him. It's the last thing she says in the book.

The notion of sanity is one of the main ideas of this comic. Jack, Judy, Patrick, and Tony are not insane, but they act in a way beyond the normal boundaries of what we consider sane. The question becomes: Are they, especially Judy, really free? She is bound to the Order, after all, and bound to Patrick in a lesser way. She's not insane, but has her insane path taken her too far, and can anything be considered "too far"? Milligan implies that nothing is too far, but in a way, he undercuts his own argument. Janet is, after all, a survivor. No one else escapes unscathed, not even Judy, who claims to have been "freed" by the experience. She has a different life, but she is still, to a certain degree, chained. She's a slave to a different kind of normality. Is her slavery any better than Janet's? Or Tony's?

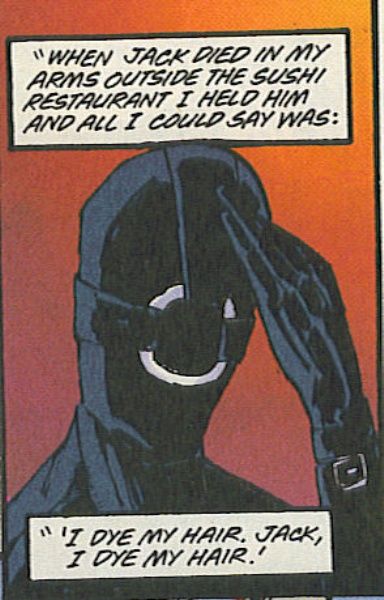

The real heart of the comic is, interestingly enough, honesty. Jack and Judy are not honest with each other, and that drives them apart and leads to Jack's death and Judy's transformation. Tony brings this up to Janet one night. He's making love to her, but stops because he imagines Jack and Judy watching, laughing at his pedestrian method. He tells Janet, "I ... I just had a thought. What if Jack and Judy had really known each other." She yells at him that they're supposed to be making love, and he responds, "I know, but ... what if they'd known how each other really felt? The things they really wanted. Maybe neither of them would have needed to be the Extremist." Jack brings this up just before he is killed, but he never gets the chance to talk to Judy about it. Even the fact that Judy dyes her hair is a lie they tell each other. Judy doesn't tell Jack, and Jack doesn't tell Judy that he knows. Ironically, Tony's moment of insight obscures the fact that he and his wife have secrets, too, and he can't reach her. Instead he delves into his obsession with Jack and Judy. Patrick is a reprehensible person, but he is honest. So, in her own way, is Janet. These two characters change not at all, because they don't need to. Milligan sets up a scenario that seems to favor leaving morality behind and indulging one's every whim, but this is a more subtle and interesting comic than that. The Extremist becomes a story about lies, and how our society and our relationships are built on lies. Being "extreme" means being honest, even if it hurts. Jack and Judy could have been honest with each other, and both would have survived. As it turns out, they were much more similar than either knew, but the lies they told each other built a wall between them. Jack attempts to break it down, but he's killed. Judy eventually does break it down, but she no longer has anyone to share it with. Therefore, it's not surprising she embraces the life Patrick offers. She has no one to share her newfound attitude, and the tragedy of the book is that this happily married couple could have found new love, if only they had had the courage to speak.

McKeever's odd art helps the story greatly, because this is a story about secrets and sex, and McKeever has a style thatmakes the entire world feel more secretive. Hisdrawings are "ugly" in that they don't show the world as we see it, but a skewed version of the world, which may be closer to how it actually is. His Extremist costume, with its leather and buckles and large ring in the center of the face, comes alive not only when someone is wearing it, but when it's draped over a chair or hanging in a closet as well. The ring in the face makes it look as if the Extremist is always smiling, a horriblyunnerving image, especially when he/she is killing someone or playing Russian roulette, as Judy does in the first issue. McKeever's drawings of the sex clubs thatPatrick frequents are also wonderfully done, with almost deformed peoplestrainingtoward their limits, their faces horribly twisted. In a comic about honesty, McKeever shows us an honest portrayal of the world in all its sad glory. His most devastatingly beautiful drawing of Judy is the last time we see her, when she isabout to put on the Extremist mask for the last time and leave our purview. Judy'sface is evil and triumphant, shorn of human emotion except total satisfaction, and it haunts us beyond the book. McKeever's books are often difficult to lookat, because he doesn't fit what we would think of as "nice-looking" art, but he's brilliant on comics like this, where the story calls for something more brutal and, to befrank, extreme.

Theshocking thing about The Extremist is not thatMilligan suggests that Judy is better off losing her soul and indulging in every fantasy. It appears that way, but despite Judy's final look, there's something a bit heart-rending in the very next panel, when she puts on the Extremist mask and gazes back into the room where her final victim lies. It's a look of pity and perhaps regret (McKeever conveys this wonderfully through body language, as she is, after all, wearing a face-covering mask), and it leaves us feeling that although Milligna, on the surface, is promoting an "extreme" lifestyle, the truth is far more unsettling, and that is that we are all extreme, and having the courage to face it will lead to a greater understanding of who we are. We don't have to go out, dress in fetish leather, and slaughter "regular" humans, but we do have to confront this animal inside us, because it destroys everything. Judy might think she's better off, but she has lost her husband, who despite his faults loved her, and she has lost all semblance of humanity. There is no need to go as far as Judy goes. What's needed is a recognition of the roiling emotions and desires we all have, and if we can accept those in ourselves and in the ones we love, then we can become better people. If Jack had been honest with his wife, his marriage and his life could have been spared. If Judy had been honest with Jack, they could have made it work. If Tony had been honest with Janet, he wouldn't have felt the need to pursue Judy to the end. That's the tragedy of this comic, and not even Judy can escape it.

It's perhaps not terribly surprising that DC has not collected this ina trade paperback, and I have no idea about either the cost or the availability of the issues. I can't imagine they would be that scarce or that spendy, but you never know.This is one of those wonderful early Vertigo mini-series,and it's definitely something to check out if you can find it. Read it with Enigma for your Peter-Milligan-sex-and-violence-fix!