I warned you that there would be more Swamp Thing, and here it is!

Swamp Thing by Mark Millar (writer), Grant "They wouldn't let me turn Swampy into a Dadaist manifesto, so I quit" Morrison (writer, issues #140-143), Phillip Hester (penciller, issues #140-152, 154-155, 157-158, 160-164, 166-171), Chris Weston (artist, issue #153), Phil Jimenez (penciller, issue #156), Jill Thompson (artist, issue #159), Curt Swan (penciller, issue #165), Kim DeMulder (inker, issues #140-152, 154-158, 160-171), Tatjana Wood (colorist), and Richard Starkings/Comicraft (letterer).

Published by DC, 32 issues (#140-171), cover dated March 1994 - October 1996.

I guess there are some SPOILERS, but honestly, I tried to restrain myself. I don't know why - usually I let the spoilers fly, but not with this one!

Post-Alan Moore, Swamp Thing slowly entered the doldrums. Rick Veitch's run is well-regarded, I guess (I haven't read it), but it's more famous for being something it's not (it's not Alan Moore's run), for the creation of Tefé, Swamp Thing's daughter, and for its abortive end when Veitch quit after DC refused to publish the "Swamp Thing meets Jesus" issue than, it seems, the actual stories.

Doug Wheeler took over, and I own his finale, "The Quest for the Elementals," which is a deadly dull arc, and I can't imagine anything before that is any better. Nancy Collins promised a return to horror, and she delivered to a certain extent, but she began to recycle story ideas too much, ending her run with the return of Anton Arcane and General Sunderland. Her run is criticized as being to soap operatic, which is not a completely untrue point, but it's a bit too facile. Collins did a decent job rehabilitating the title, and she did rip apart Alec and Abby's marriage and send Tefé off to South America with Lady Jane and the Parliament of Trees, so there was that. But for 70-odd issues after Moore left the book, the title foundered a bit. And it was Moore's fault, really.

The problem with Moore was that he did such a radical redesign of the character that writers couldn't figure out how to have Swamp Thing interact with the DC Universe without him being the most powerful and conscientious member of that Universe. It's the age-old problem with superheroes - why doesn't Superman save the world? - but it was a bigger problem with Swamp Thing because Moore made him directly responsible for the maintenance of the "Green," and his new understanding of that role and his powers made it so that not doing anything would be too gaping a plot hole. Moore himself avoided this question by throwing Swampy into space and then, when he returned, having him give up his role so he could play house with Abby deep in the swamp.

Veitch apparently avoided it by creating Tefé as a new plant elemental and then sending Swampy through time so he could meet a bunch of characters from DC's history. Wheeler avoided it by creating a big enemy for the Green that Swampy had to defeat. Collins avoided it by turning the title into a domestic drama, even as Lady Jane began tutoring Tefé in her abilities. But the title was spinning its wheels a bit, and it seemed like no writer really knew what to do.

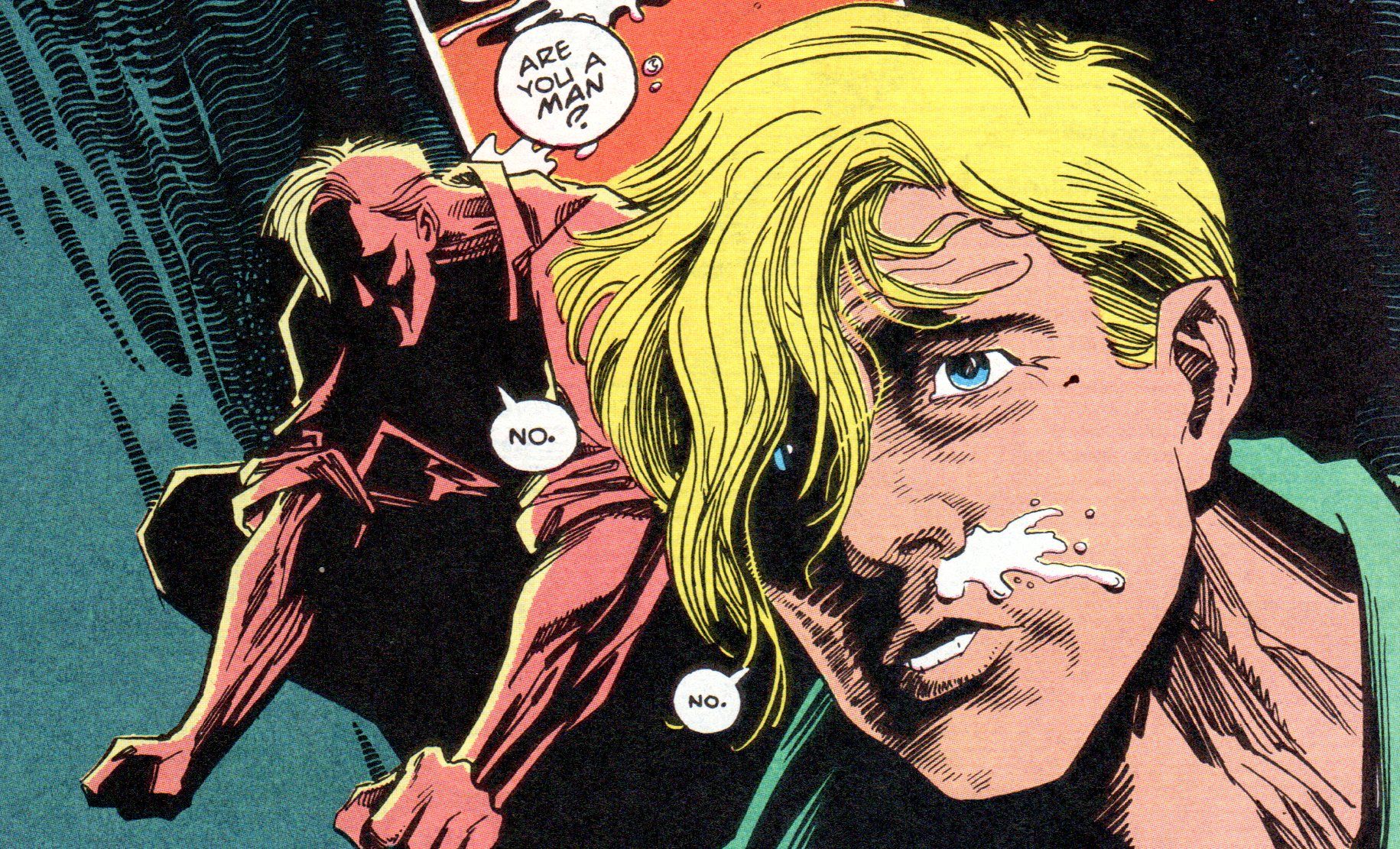

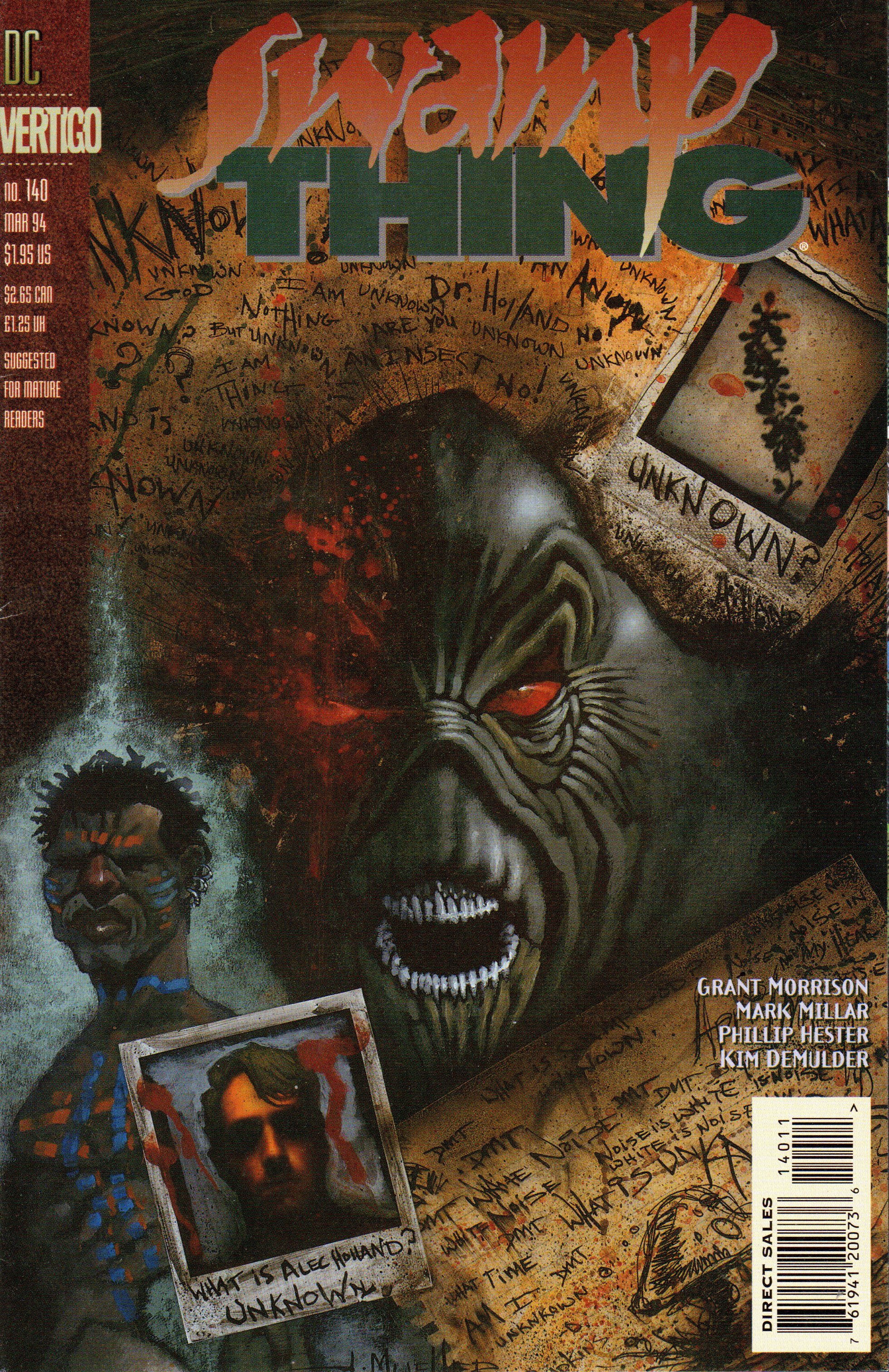

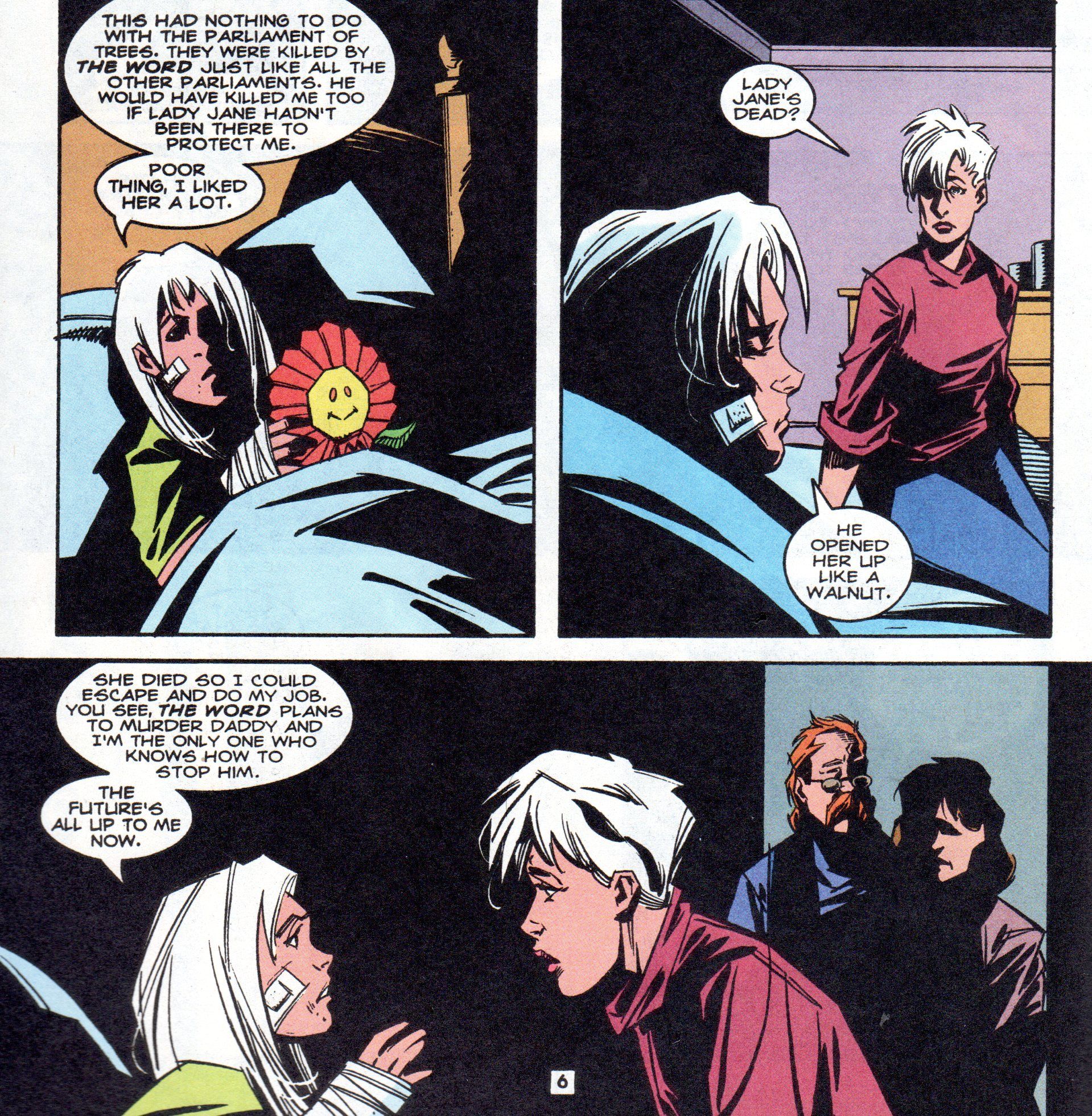

Then Mark Millar came on board, with an assist on the first four issues from Grant Morrison. His run on Swamp Thing, which he began writing around the time he turned 24, remains the best thing by him I've ever read, and it's partly because for whatever reason, he took the character to its logical extreme. I doubt if sales were bad enough, at least early in the run, that DC decided to cancel the book once Millar finished his run, but they allowed him to go as far as anyone could with the character, and cancellation was really the only logical thing left to do. So Millar was able to create a magnificent epic that was not only terrifying, as he gave us the best horror on the title since Moore (and Millar's horror was far nastier than Moore's was in many ways) as well as a wonderfully inspiring story. Millar and Morrison know they have to deal with what Moore did on the title, but instead of simply tying to deal with it by ignoring it, they embrace it. The run begins with Alec Holland waking up in Peru after having dreamt he was a swamp god. The reader knows it's not Alec Holland - DC, Millar, and Morrison wouldn't be so foolish as to wreck what Moore did to the character - but it's still an intriguing mystery. Why is Alec Holland in Peru, and why is a crazed, murdering Swamp Thing rampaging through Louisiana?

It's unsettling in the best way, unlike Nancy Collins's run and very much like Moore's ... without slavishly copying what Moore did. Millar (and Morrison) don't ignore what Moore did as much as confront it head-on, and that's part of why the run is so good.

The reason we get Alec Holland and Swamp Thing, separated, makes perfect sense, and it's part of the reason why continuity between writers shouldn't be overlooked. Millar recaps portions of Collins's run well (this was the first time I had ever bought Swamp Thing, mainly because Morrison was writing it, so I hadn't read Collins's run yet, but I wasn't too confused), but there's no doubt that she did the heavy lifting when it comes to isolating Swampy and causing the events of the first four-issue arc of Millar's run. Without Collins's run, Millar and Morrison's story of a Swamp Thing bereft of humanity is terrifying but the smallest bit less tragic, even though the writers manage to make it work. With Collins's run, the first four issues become sadder, because we know a bit more about why Swamp Thing is killing indiscriminately. Alec Holland's twisted journey from Peru to the United States is horrifying on its own (in issue #142, we get the explanation for what has happened as he rides the Soul Train), but because of what happened when Collins was writing the comic, it's even more tragic. And Alec's and Abby's reunion in the Arizona desert becomes not only a crossroads for Alec, but a watershed in their relationship, the groundwork for which was laid by Collins. If it sounds like I'm suggesting that Collins's run should be included in this post, I'm not.

Collins's run is, as I noted, not bad, but not necessary because Millar and Morrison do such a good job in those first four issues of, basically, recapping it. But the continuity with the previous run, and not just Moore's run, is nicely done and adds a bit of nuance to the terror of the first four issues of this run.

Millar isn't just interested in horror, either, which is nice. He uses horror and terror very well, but his overall story is more uplifting than that. Once Moore introduced the Parliament of Trees, it seemed like it was only a matter of time before someone wondered if there were other Parliaments (besides the Funkadelic kind), and Millar did just that (to be fair, Wheeler toyed with the idea of an alternate Parliament, too). So he uses his big arcs to give us the Parliaments of Stone, Waves, Vapors, and Flames, before the big surprise in the title's final issue. By couching his horror writing in a grander story, Millar is able to make the horror about something - Swamp Thing has to pass tests in order to gain access to these other Parliaments, and the tests are often horrific. We see this even in the first story arc, in which Alec Holland has to come to terms with being Swamp Thing, something Millar implies he never did, as he continued to act too "human." It's a clever idea, and early in the run, Swampy can't even accomplish that - he's the one who wants Abby back in issue #143, and she's the one who rejects him. This isn't too surprising - she had already rejected him at the end of Nancy Collins's run - but Millar and Morrison gave us a Swamp Thing who recognized his mistakes and was willing to change. Abby's rejection is the first in a line of events that break away his humanity bit by bit.

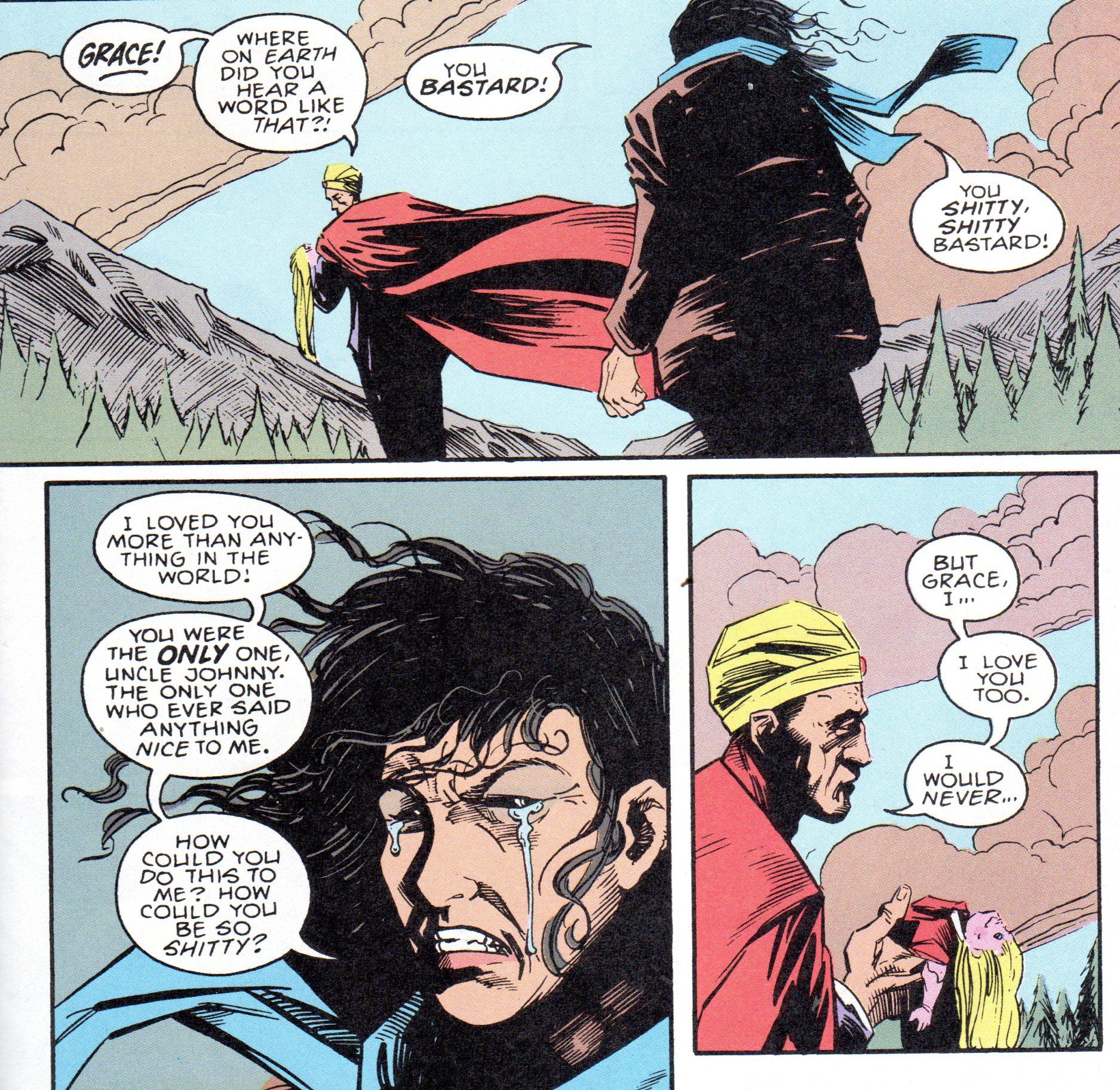

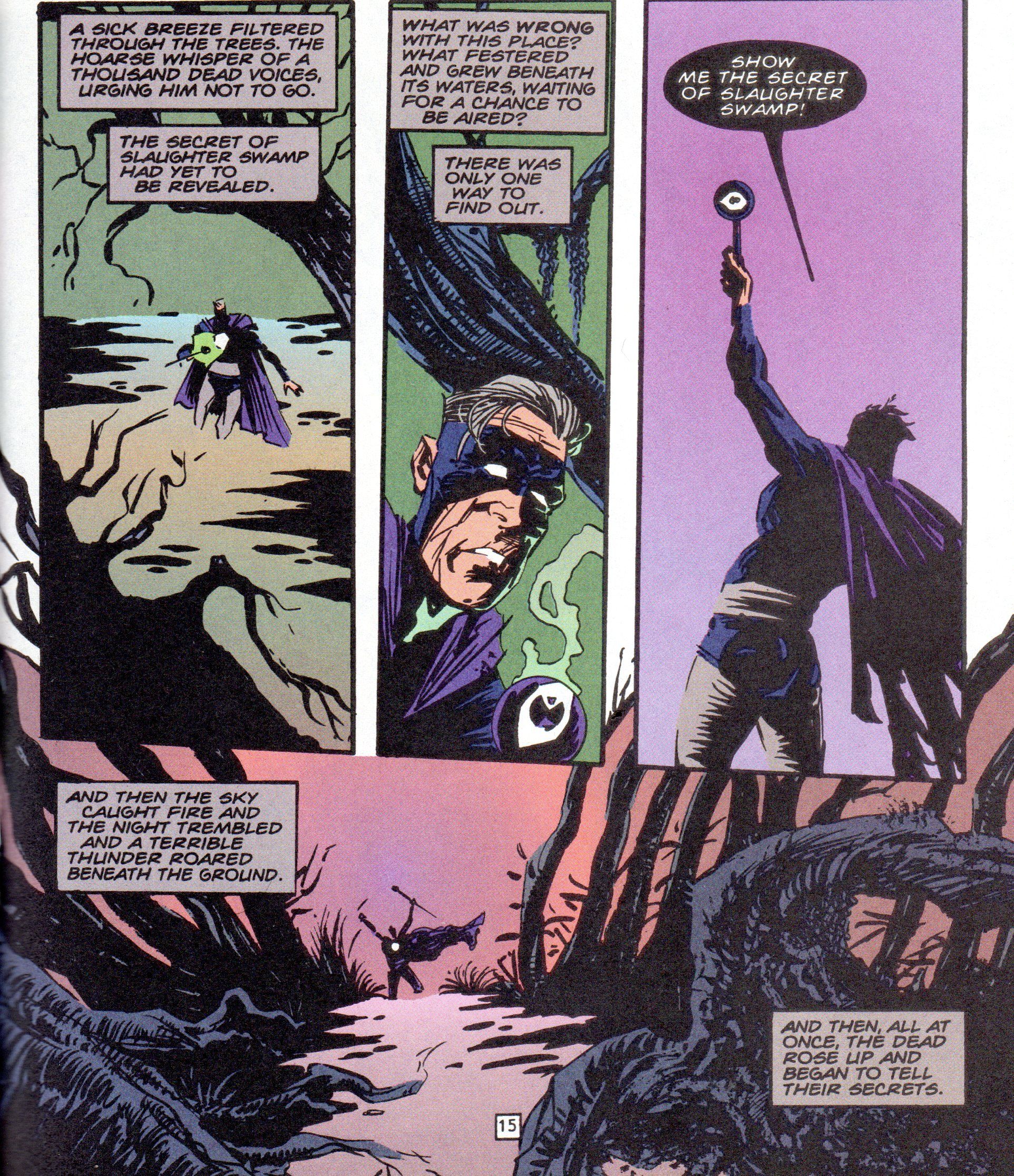

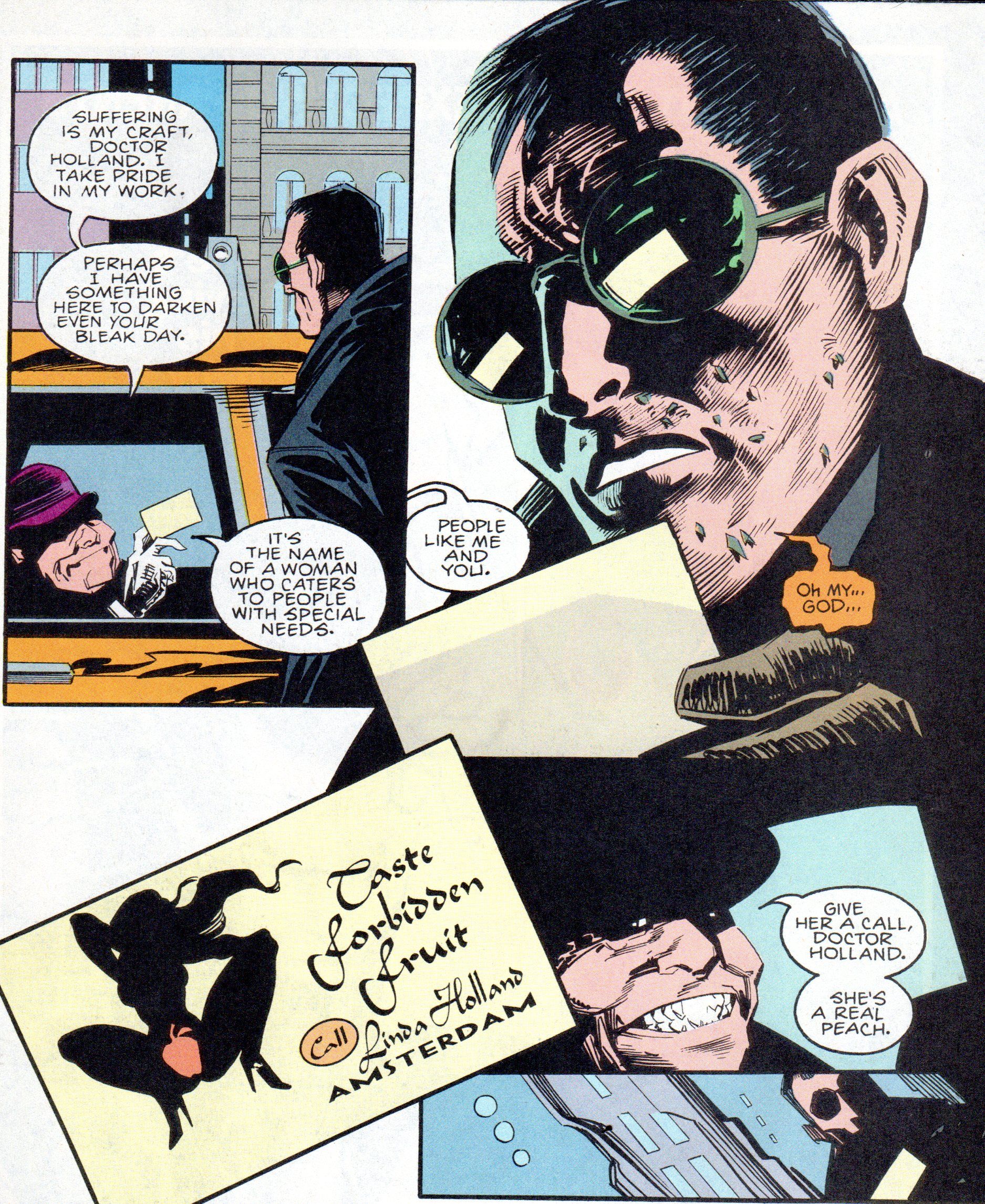

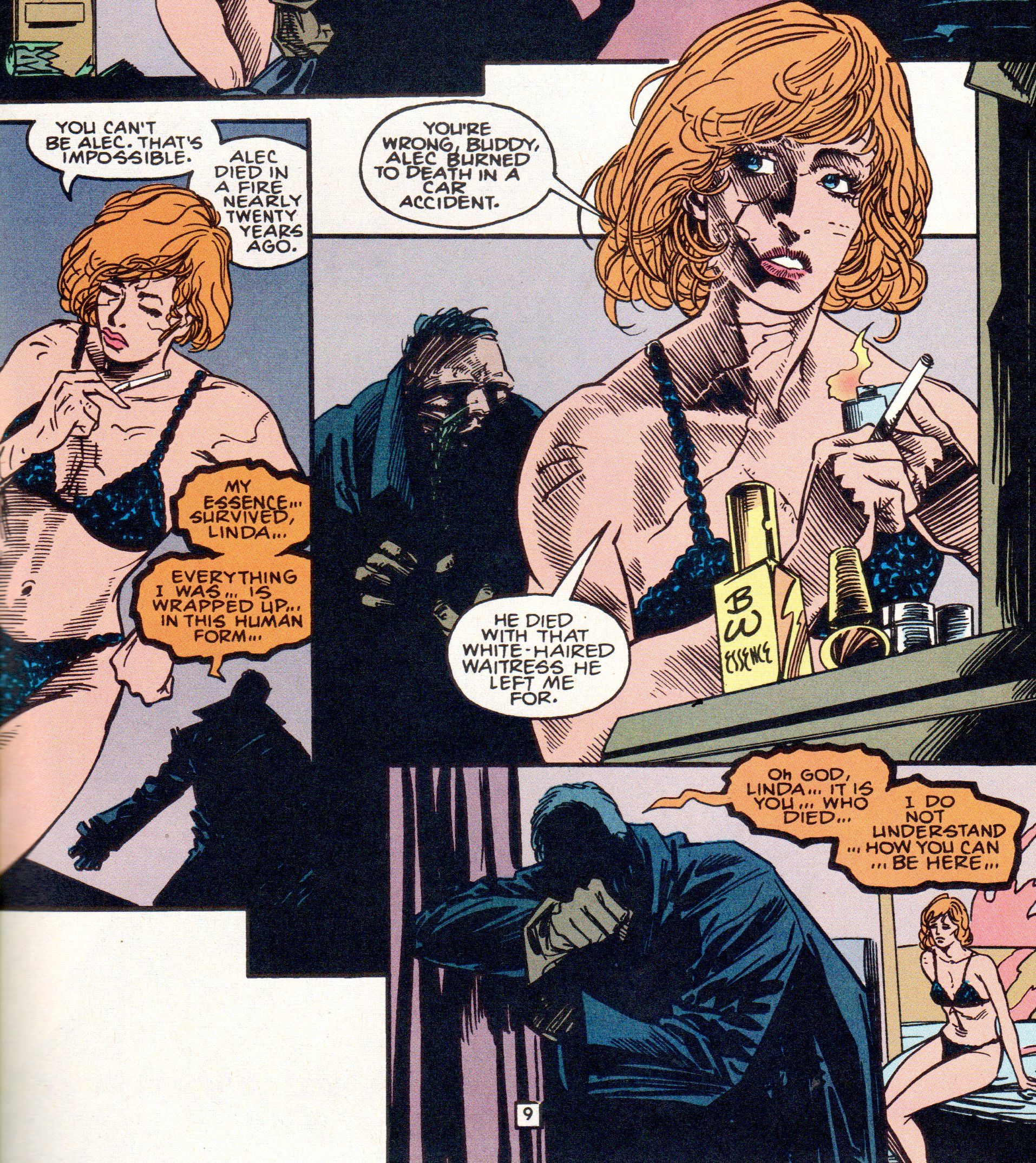

Holland had already met the three men who guide his destiny throughout Millar's run (the Fates?) - Don Roberto helped wake him up, El Señor Blake told him how to get out of Peru (meaning the strange hell he was in), and the Traveller explained what had happened to him. Each of them point him on his road, and then a demon in issue #144 puts him on the road to Amsterdam, where he'll find Linda Holland turning tricks. Linda's secret is terrifying, and I won't spoil it, but it is yet another small rip at Swamp Thing's "humanity," as he forces himself to excise that part of his past. Swamp Thing heads to the Black Forest and fights the Parliament of Stones' champion, and Millar has him lose a bit more of his humanity when he figures out non-human ways to fight. The humanity in the story comes from Sargon the Sorcerer, whom Millar resurrects (after Moore killed him in issue #50), and Sargon's niece, Grace (a bit on the nose with the name was Millar, but still). As Swamp Thing becomes less human, Millar does a nice job showing actual humans displaying positive human traits. In the next arc, "River Run," Millar gets to indulge in his love of Elseworlds tales but continues to strip Swamp Thing of his connections to his old self.

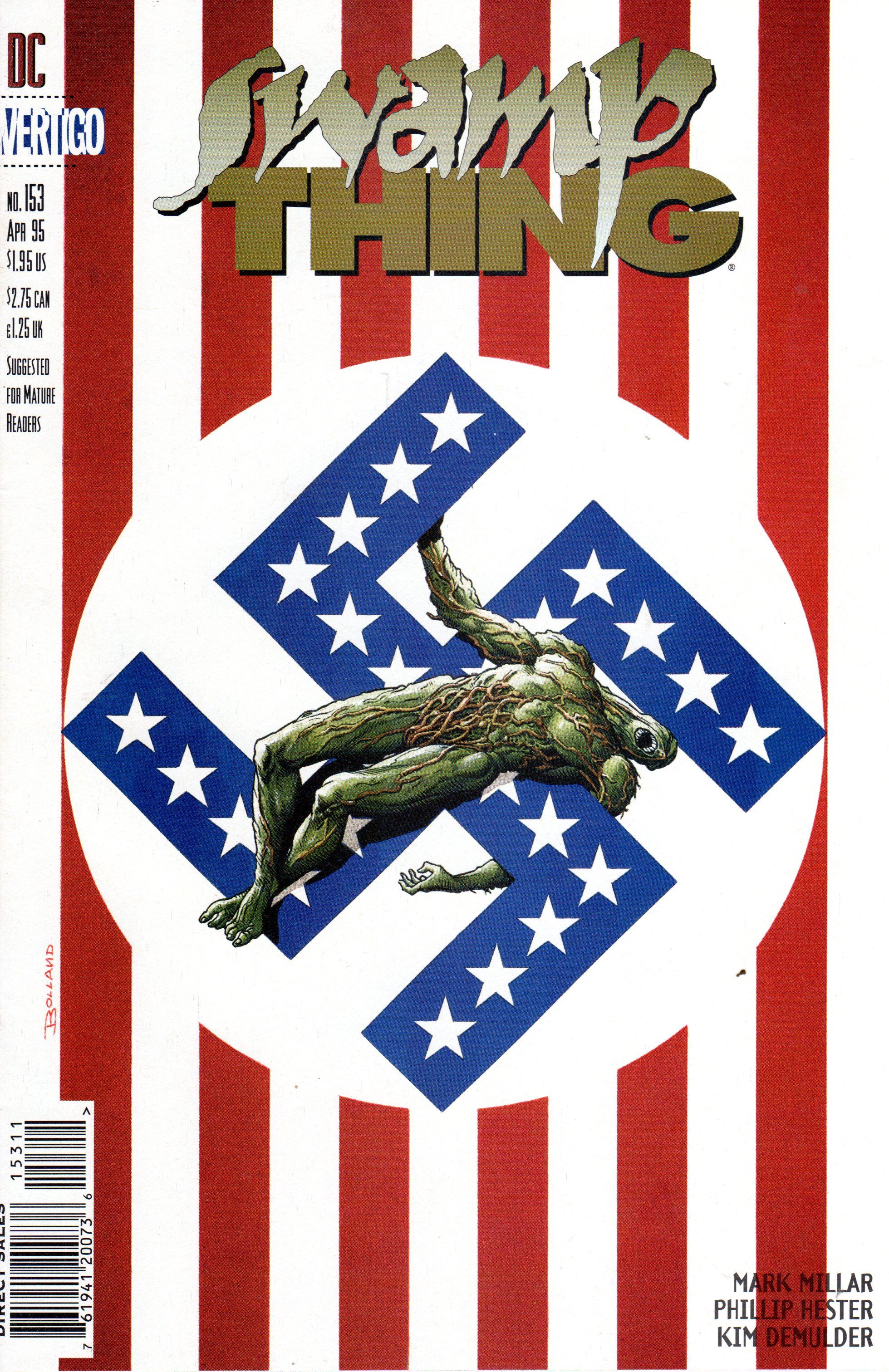

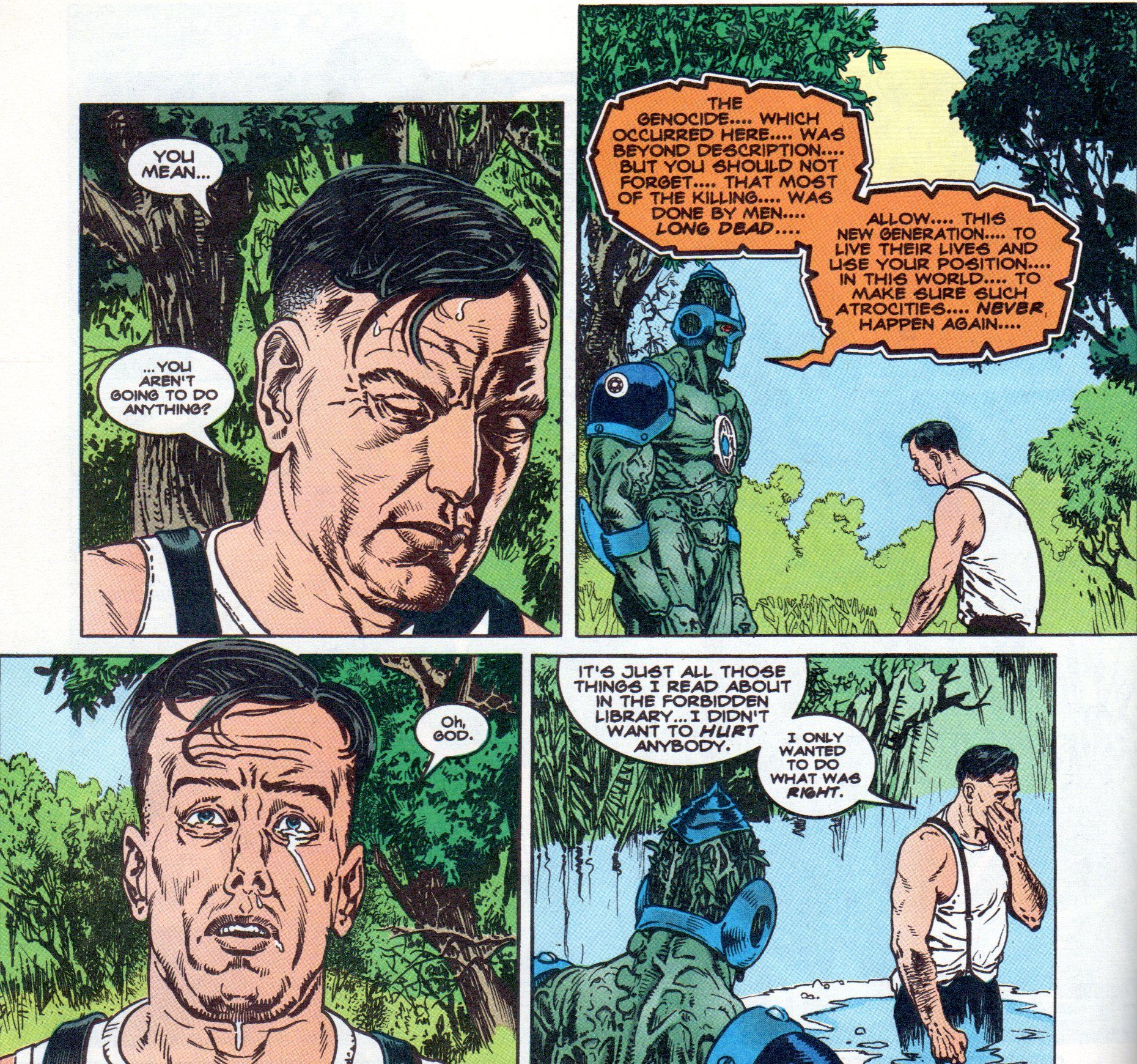

He has much in common with the Devolving Man in issue #152 and knows how to get it to stop killing; he refuses to destroy a Nazi-ruled world in issue #153 because the Nazis are living in harmony with the environment and Swamp Thing doesn't care about avenging their long-dead victims; he meets versions of Abby and Anton Arcane in issue #154 and isn't able to see the truth of what's happening; and he can't stop thugs from killing Alec and Linda Holland in issue #156. Each of these events removes him even further from "Alec Holland," even though his compassion for Anna, the main character of "River Run," is what helps him become the Parliament of Waves' champion. Millar continues to indulge his love of weird and obscure DC lore when he brings back Nightmaster for "Atmospheres," the next arc, but in terms of what it means for Swamp Thing, he brings back Abby, who has changed her mind and wants to stay with Alec. In a twist, of course, now he rejects her, not because he doesn't love her, but because he knows more trials are coming and he's afraid of what he might become. In issue #161, Millar finally makes overt what he's been doing the entire time, as Swampy tells Abby, "My emotions grow more abstract every day ... no matter how hard I fight it ... This erosion of my humanity ... has provoked something I have seldom experienced ... in recent years ... I believe ... in a very distant way ... I'm scared, Abby ..." In issue #162, she leaves, but not before (somewhat unfairly, in my opinion) expressing those very same fears, that Alec is becoming more of a monster every day. By the time he passes the Parliament of Vapors' trial, Swampy is no longer sure he wants all those powers. He tells the Parliament, "The terrible power already within me is stripping away what's left of my humanity and I fear for the world below," but they dismiss him: "Now when we send you back to your home in the swamps your physical body will be as alien as the new perceptions prepared for you cherish these human doubts and insecurities now because they will be your last everything you have feared is about to come true" (the Parliament of Vapors don't use words, just thoughts, so they have no need of puny punctuation!).

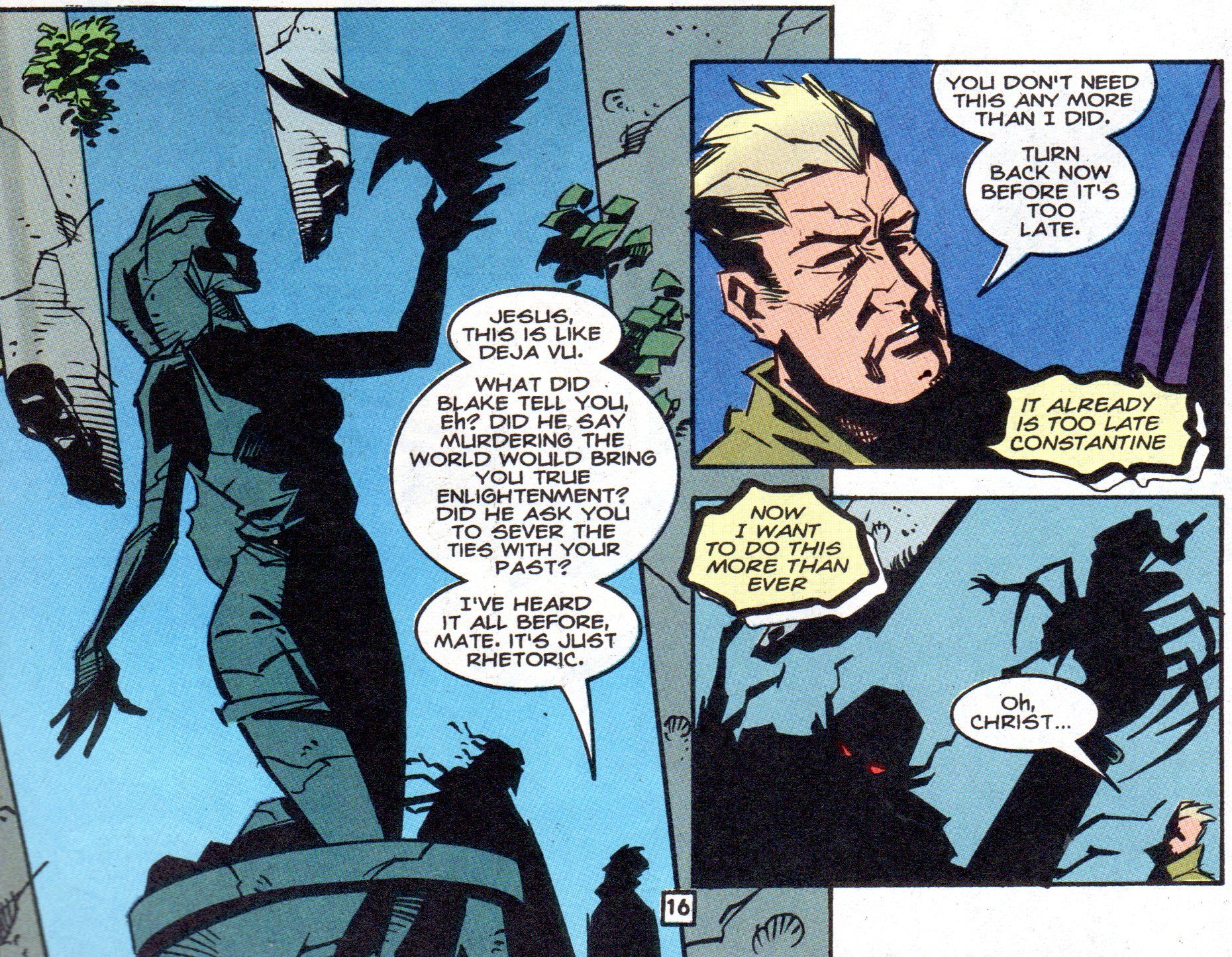

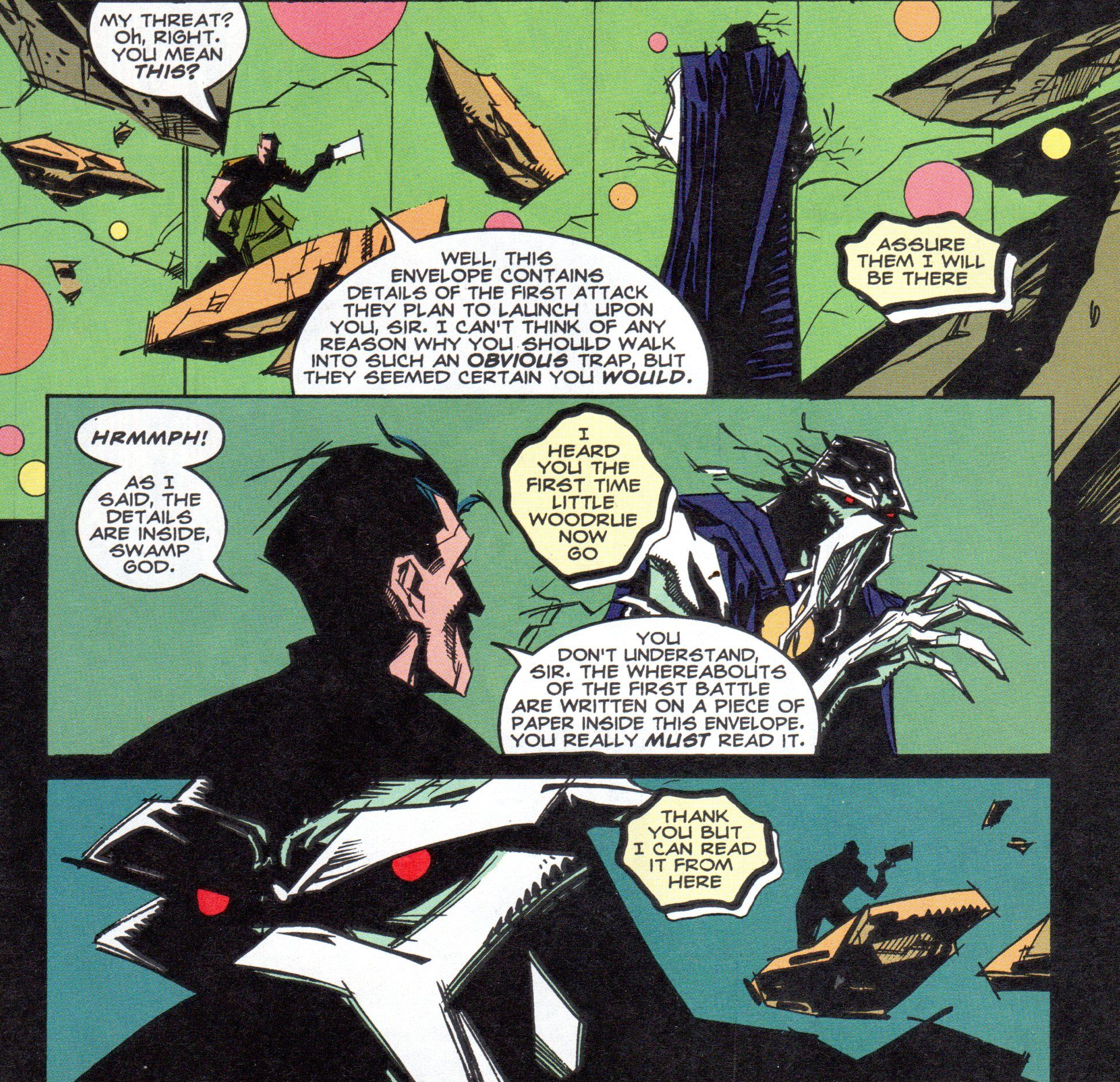

In the next arc, "Trial by Fire," Swamp Thing has left all semblance of humanity behind, as he only takes the shape of a vaguely humanoid figure to converse with the characters sent to talk him down from global destruction - Jason Woodrue and John Constantine, two people the powers that be think can get through to him. Millar has done such a good job taking away his humanity that until the very end, we're not exactly sure what Alec will do. Of course, the world doesn't end (it's a DC comic!), but the brilliant thing about this run is that Millar makes us believe, just for a moment, that it might.

Swamp Thing's transformation into, basically, a god, is a theme that Millar likes to return to, but he rarely does it in other comics with as much subtlety, panache, and just good storytelling as he does here. Millar understands the cost of it, something Swampy recognizes too late, and he creates characters early in the run who also know what it will cost Alec and others who try to stop him. The three "Fates" who send him on his way are manipulative bastards, but they realize that the world is struggling and only Swamp Thing can save it.

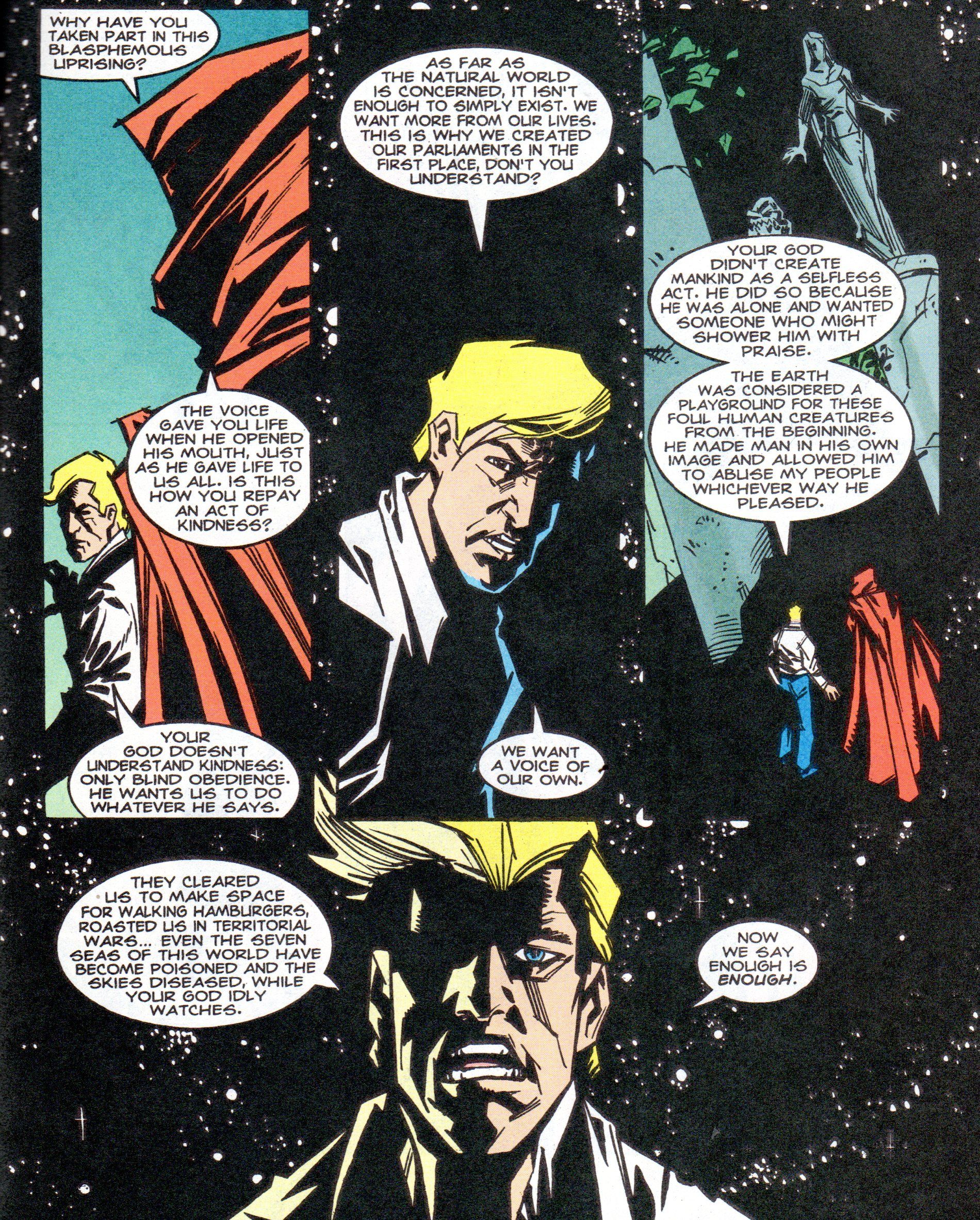

The idea of destroying the world to save it is not new, of course, but it's not usually done with the hero acting as the catalyst. In later Millar comics, he would use ostensible villains to explore this theme (even his Authority were, frankly, douchebags), and in most media, it's the bad guy wanting to wipe humanity away to save the planet. Millar turns that on its head, giving us the main character, the hero, as the one who decides he's going to do it, which makes this one of the most interesting stories in that trope to exist. As I noted above, he pleads with the Parliament of Vapors to keep their power, as he's finally realized what it means, but the fascinating thing is that they're the final parliament. He could have turned away before, like all the champions of the Green before him, but of course, then he would have been destroyed himself. And Millar sets it up so that each trial is something that feels necessary at the time. Nelson Strong, who becomes the Stone champion, is hunting him, and that doesn't stop just because Nelson dies and becomes a Stone elemental, so Swampy has to defend himself. The Parliament of Waves' trial is a bit more subtle, as Swamp Thing needs to learn to accept different vantage points as he travels through different realities (even though he misses the point of the most crucial reality he enters, as I noted above), but ultimately, it's his compassion that allows him to move on as the Blue champion. If Millar had taken that away, it wouldn't be the same character, so it makes perfect sense that he would triumph in that trial.

Finally, the Vapors' trial forced him to use his brilliant intellect, another aspect of his character that he simply could not turn off. All of this leads to "Trial by Fire," in which Millar shows us a Swamp Thing who has become the most powerful being on the planet, and one whose essential character has led him to that place. When he speaks to Woodrue or Constantine, we still get vestiges of his former self, which makes it all the more tragic and powerful that they can't convince him to stop doing what he's doing. When he faces off against the Word (it's a great confrontation, marred just slightly by James Bond Villain Syndrome), we see the old Holland, imbued with the new Holland's consciousness. The run would work fine without readers knowing anything at all about Swamp Thing, but because Millar uses what we do know about him, it makes the work hit harder.

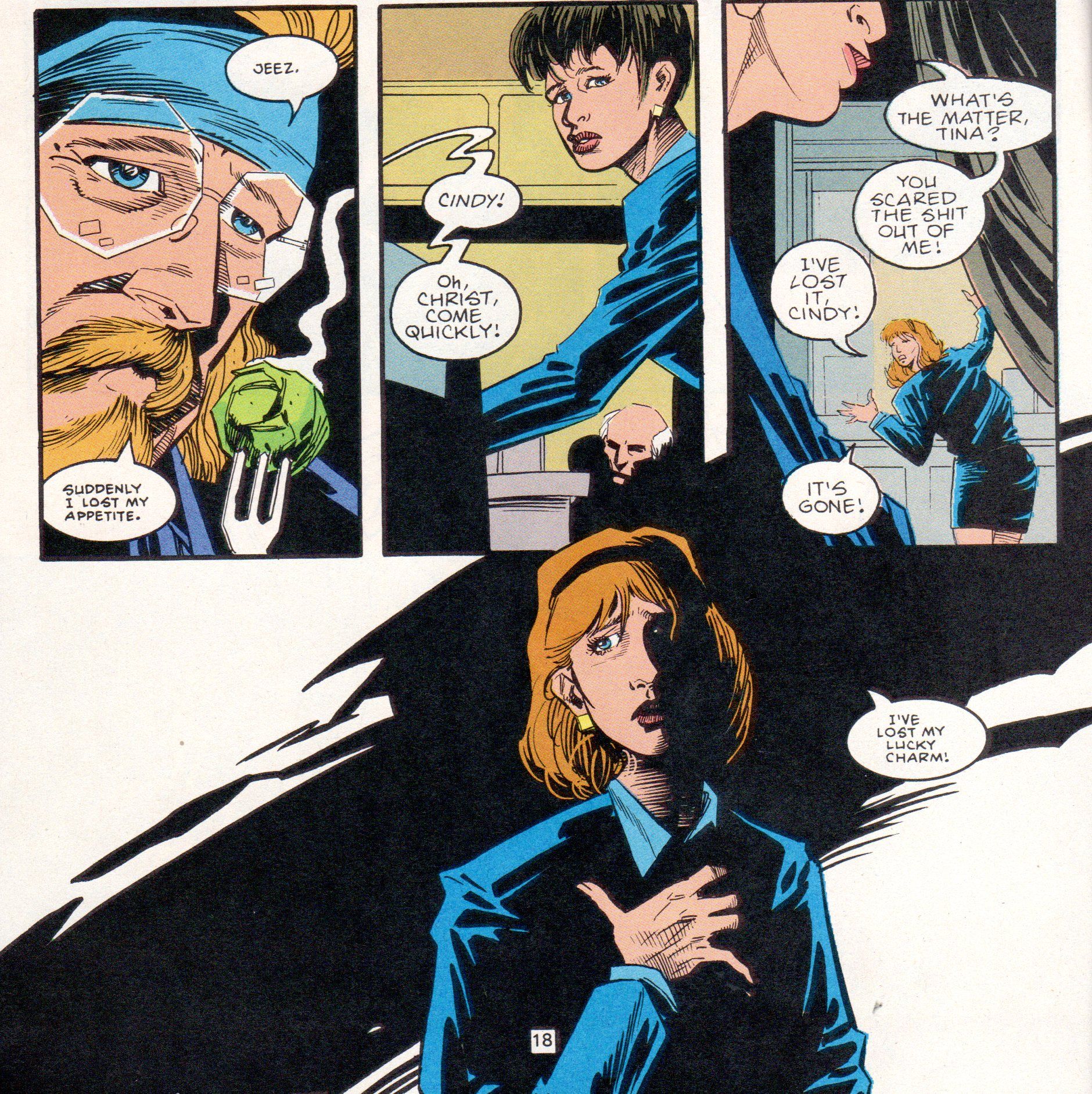

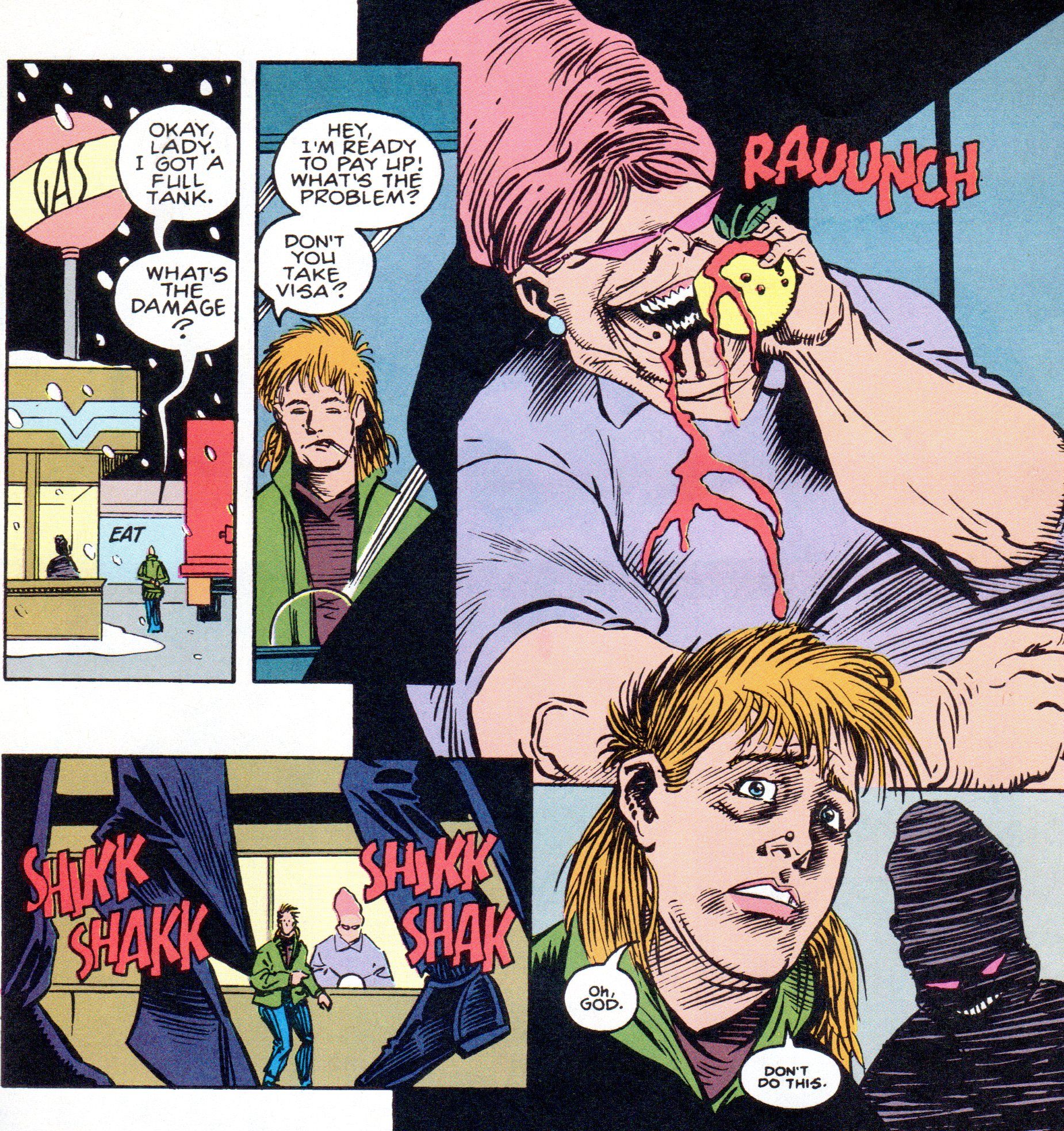

As I noted, Millar's horror is nastier than Moore's in a lot of ways, mainly because his horror is more personal than Moore's was. Except for the situation where Anton Arcane possesses Matt Cable, Moore's horror happens to people that Moore introduces just for that story. Millar does this too, but his horror tends to gets to Swampy and Abby the most, and even when it affects someone like Anna, she's a recurring character, so when it does happen (in issue #157), it's very disturbing. He has a way of digging into the true evil of horror, so that reality itself seems broken, even when we know things are occurring that can't possibly happen (in the context of the comic book universe Swamp Thing lives in).

Just the idea of Alec Holland waking up in Peru is upsetting enough, and his disorientation mirrors ours. When he arrives in New York, he takes the form of Matt Cable to divert suspicion, and Millar makes it just creepy enough for it to be uncomfortable. Linda Holland's appearance is bad enough, but her specialty is truly horrifying, especially as we can believe there would be a market for her skills. Sargon's plot in the Black Forest involves ritual sacrifice, and you might be able to imagine what horrible things Millar does with that. The horror comes from more overt places, of course, but Millar can also be subtle, as when he gives us a Solomon Grundy possessed by Swamp Thing in issue #155. He can also give us tragedy (often but not always tinged with horror), and that's also what elevates the run. The interactions between Alec and Abby are very well done, but throughout, we get people struggling to find the right words, people keeping secrets that tear them apart (which is always fertile ground for great fiction), and people losing everything due to forces beyond their control. Millar's excellent work with Grace and Sargon makes the end of their arc beautiful, while his destruction of Anna is both horrifying and tragic. Millar does great work with Jim Rook, showing a man who was once on top of the world and appears ready to give up, only to receive a second chance at redemption. What Millar does with that chance is both gripping and tragic. It all comes to a head in "Trial by Fire," as Abby enlists Chester Williams and Liz Tremayne to convince Alec to refrain from destroying the world, and it doesn't go quite as they planned.

Part of Alec's plan involves Tefé, and the way Millar shows us what parents are willing to do to help their kids is tragic, as Abby makes a difficult choice about her daughter. Even more tragic is what happens when she helps Alec, as she learns a hard lesson about humanity or lack of it. Millar shows a wonderful understanding of human nature and its darkness, which helps make the horror worse and helps make the tragedies more devastating. Horror is great and all, but if the reader doesn't care about who it's affecting, it's not as powerful. Even in issue #159, "Swamp Dog," Millar takes a terrifying situation and manages to imbue it with such humanity that the tragedy stands out, so much though that the "happy ending" is shot through with despair. (The less said about issue #165, the Elseworlds tale in which Chester Williams becomes a fascist cop, the better. Curt Swan's art, done just before his death, is solid as ever, but Millar indulges in the worst excesses of bad satire, and it's interesting today only because it shows where he was headed with his writing. If you buy these in single issues, you can safely skip this one.)

Phil Hester was also in his 20s when the run started (he was born in 1966) and this was his first big book - he had spent five years or so doing work for First, Caliber, and Dark Horse. He drew 28 of the 32 issues, and his jagged artwork helps unify the run and also provides terrific visuals that fit the tone beautifully.

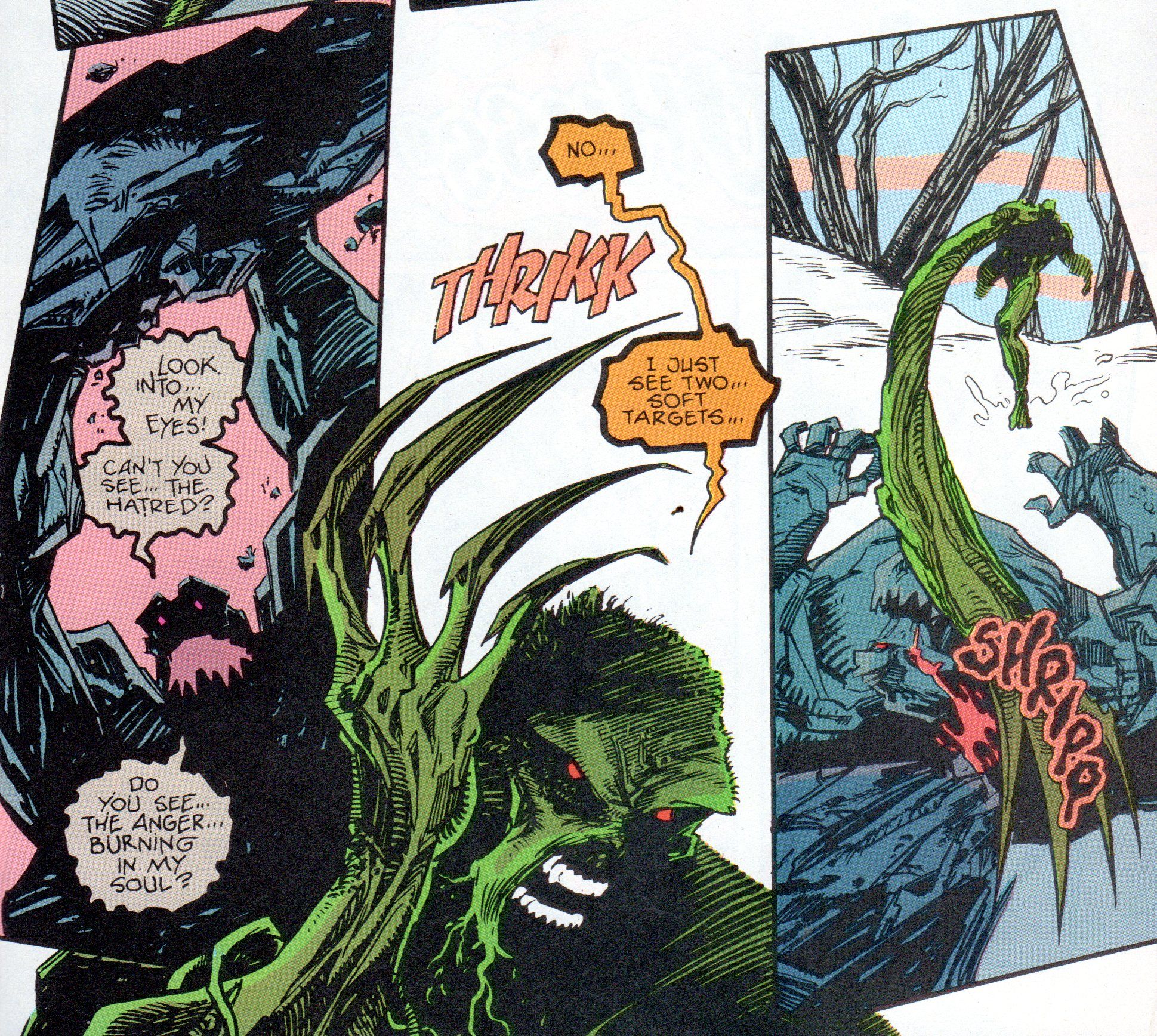

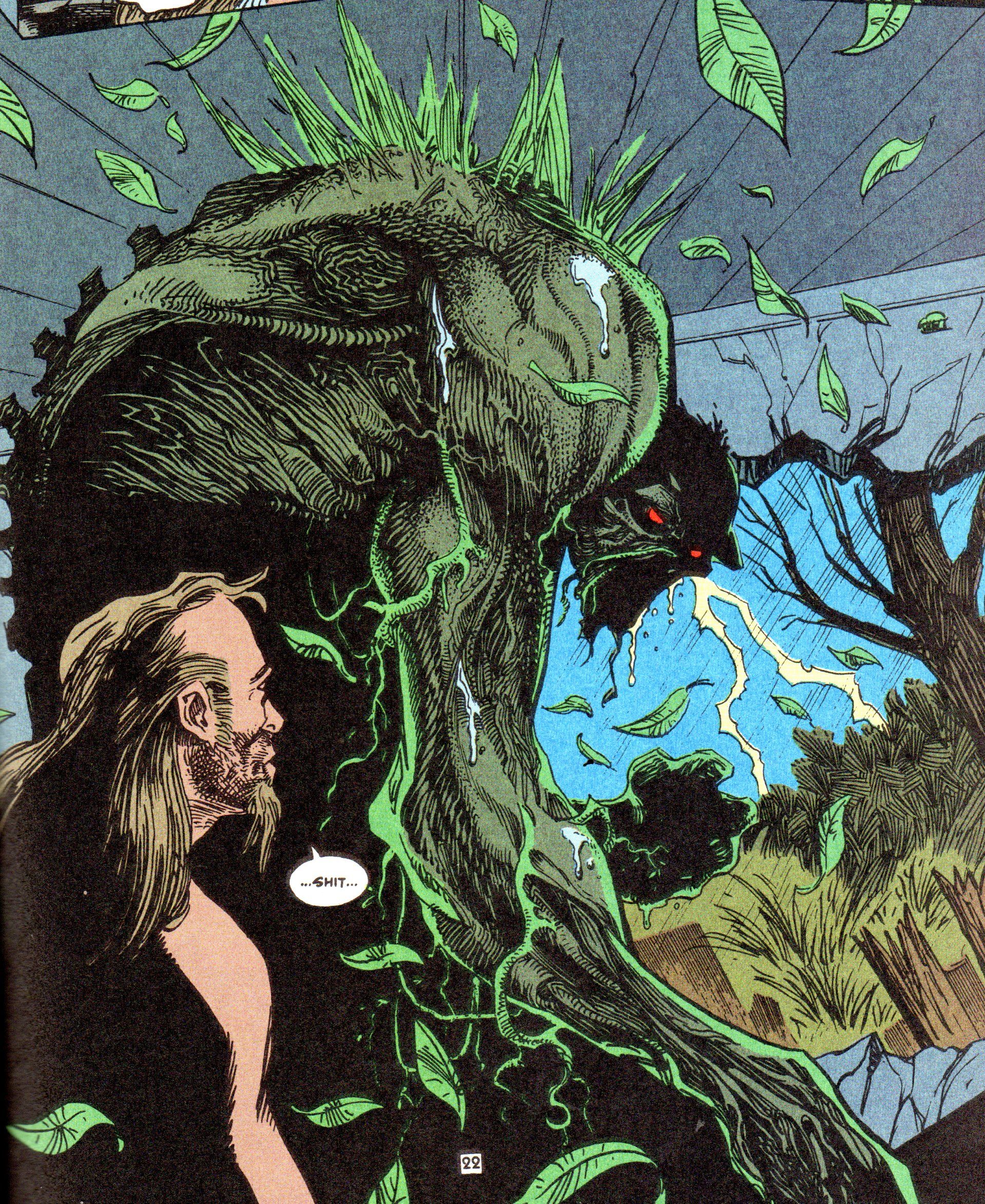

Early on, Kim DeMulder's inks were similar to the ones he used on Scot Eaton's pencils toward the end of Nancy Collins's run, which seemed to be similar to John Totleben's on the title when Moore wrote it, and I wonder how deliberate that was. DeMulder used thin, delicate hatching a lot early in the run, but later (because of time constraints?), his work became a bit rougher. Hester and DeMulder make a great team, however, as they match the ferocity that Millar brings to the writing. Scot Eaton's pencils on Collins's run are beautiful (and inked by DeMulder, they're even nicer), but they match her more "domestic" tone (and, yes, I'm still aware that Collins brought horror back to the book, but not quite enough). DeMulder, interestingly enough, is an example of inking having a large effect on the pencils, as he inked most of Collins's run (even before Eaton came on board), and his inks provided a unifying look for the book over such pencils as Tom Mandrake's, Jan Duursema's, or Russell Braun's. Hester's angular style, however, resists DeMulder's inks a bit better, forming a wonderful gestalt. Hester draws a terrifying Swamp Thing - the first time we see it, in issue #140 (well, after the first page, which is a recap), it's about to kill the people crashing in Chester's house, and Hester draws it with stegosaur spikes down its spine, a shadowed head (with Tatjana Wood providing the wonderful red eyes - I didn't check, but I think Wood and letterer John Costanza worked on every issue of this series, no matter who was writing or drawing it, which is pretty cool), a misshapen body, and long, sinewy, powerful arms.

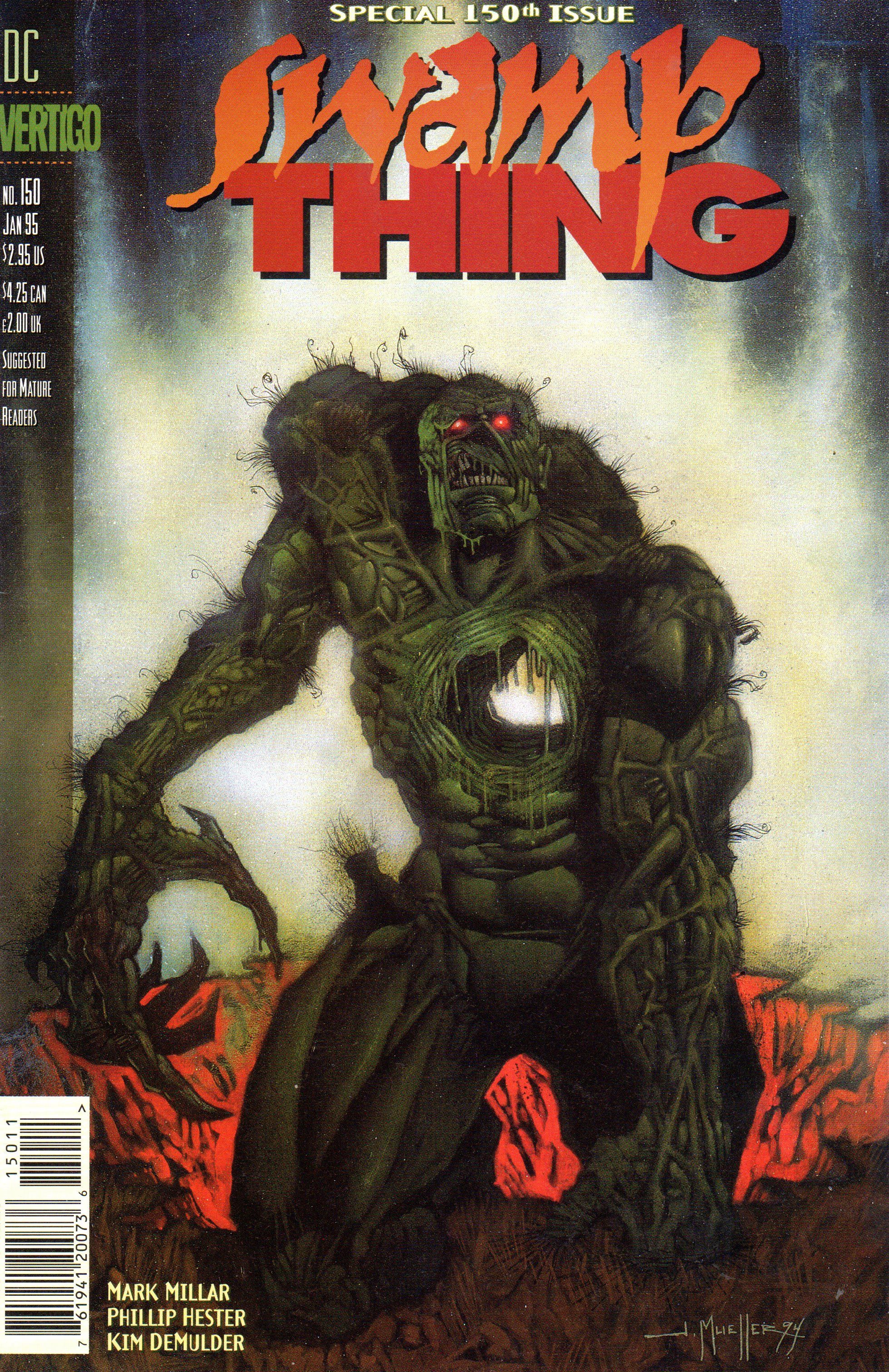

It's a true monster, and Hester does amazing work with it. Throughout the first arc, whenever we see Swampy, we see the monster, and Hester is terrific at its facial expressions and body language (it can't talk), showing that it's confused, angry, and even in pain because it's separated from Alec. When the "real" Swamp Thing returns, Hester is able to draw it more like a "man," with pleasant greenery growing from his shoulders and tenderness in his face. Hester is great at the twisted reality through which Holland must navigate, drawing perhaps the scariest Boston Brand this side of Kelley Jones, a creepy Matt Cable who can't stop the sprouts from growing out of his face, a horrifying yet vulnerable Linda Holland, a disturbingly sexy Lady Jane, and a skeletal El Señor Blake, which makes his relief after he defeats the Word in issue #150 both funny and chilling. Hester is excellent at twisting the real into the horrific, so when Grace or the truck driver who gives her a ride to the Black Forest sees what's happening in the town of Freiberg, it gets under our skin as much as it gets under theirs. Millar doesn't explain everything in the run - what the Word saw in Blake's mind, what the tattoo on Harry's back is - and it's up to Hester to make sure that even if we don't get the backstory, we get the characters' reaction to them, and Hester creates a world behind the words that we get emotionally if not intellectually. Because Hester is so good at the horror aspect of the book, it's impressive that he's able to do so well with the more majestic aspects of the book.

It's not surprising he draws an imposing Parliament of Stones, and his deep-sea Swamp Thing is impressively crusty, but his Parliament of Vapors is stunning (and may have something to do with DeMulder's inks, as they are hatched very nicely), and his "new" Swamp Thing in "Trial by Fire" is still jagged but far more regal than his earlier incarnations. His demon that possesses Timothy Raven in issue #167 is disgusting and terrifying, and what it turns Raven into (which I don't want to spoil) fits in well with the earlier artistic versions of the thing, but with Hester's interesting spin on it. The final issue is beautiful, too, especially the penultimate time we see Abby, which is tremendous. Hester was an unusual choice for the book, but it's become one of those runs where it's difficult to believe any other artist could do as good as job as he did. The four artists who fill in for him show this pretty well. They're all great - Chris Weston's clean style is excellent for a sterile world like Nazi America, Phil Jimenez's precise lines (with DeMulder again "Totlebening" the pencils with his superb inks) fit with the "real-world" nature of his story of Alec and Linda Holland, Jill Thompson is able to do genteel monsters very well, and Curt Swan's meat-and-potatoes style works well for Millar's unsubtle satire of political conservatives. But none of them seems like they'd be able to bring the twisted horror of Millar's writing to life consistently as much as Hester could. His rough, angular style fits the tone of impending doom that runs throughout the book, and he does so much visually to make Millar's words hit harder (Swamp Thing's journey on the Soul Train and through Amsterdam early in the run feature lots of scary writing, but the visuals make it far more disturbing) that it's almost impossible to imagine another artist doing as well.

That's one mark of a truly great comic, when you can't even think of another artist working as well with the writer. Hester sticks mostly to writing these days, but his art is always interesting, and on this comic, it's tremendous.

DC finally got around to collecting these in trades - the first two volumes (through issue #160) are already out, and the final one has been solicited and should be out in July, I think. I know some people think Millar's work on Superman Adventures is great, but I've never read those, so this remains the best thing by him I've read. A lot of the themes he would continue to explore show up in this work, but for whatever reason, he does a better job examining them here than he does in later work, and when you combine that with the excellent horror he brings to the title, this is a book that stays with you. It's the only Swamp Thing that comes close to Moore's, and in some ways, it's superior to that seminal run (yeah, I said it). Go get the trades and be ready to read it with the lights on! And don't forget to check out the archives, where the 'S' titles continue to grow!