"Torment" - a great Spider-Man story, or the greatest Spider-Man story? The debate begins below!

Spider-Man by Todd McFarlane (writer/artist; colorist, issue #4), Rick Parker (letterer, issues #1-5), Bob Sharen (colorist, issues #1-3), and Gregory Wright (colorist, issue #5).

Published by Marvel, 5 issues (#1-5), cover dated August-December 1990.

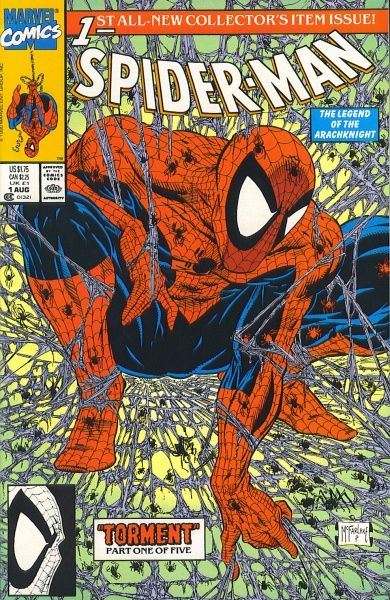

WhenMarvel announced that Todd McFarlane, the ultra-hot penciller of one of their flagship titles, Amazing Spider-Man, wasnot only goingtodraw but writea brand-new Spider-Man title, the news was greeted with disbelief by fans who could not believe that theastonishingly talented Mr. McFarlane could actually write a viable comic book. Then, when it arrived, it became not only the best-selling comic of all time, but it garnered bushels of critical acclaim. McFarlane, it seemed, could do no wrong.His limitless talent is one reason why this is simply the greatest story in the history of comics.

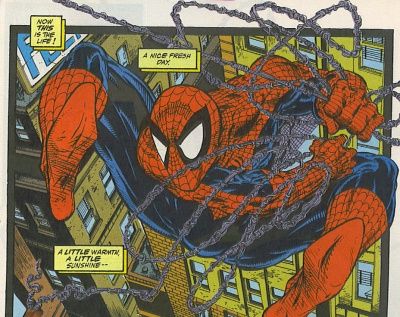

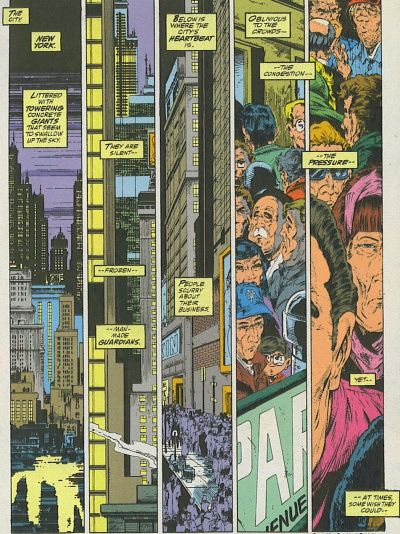

We begin with the art, because that's where everyone knew McFarlane would shine.Let's look at the very first page of his epic, where heuses five thin panels, leading into a double-page splash that properly gets us into the swing of the story (so to speak).His use of thin panels plays to the fact that the action takes place in New YorkCity, home of the skyscraper, and therefore the panels become, almost literally, the skyline of the city itself. When he uses these panels, as he does liberally, he creates a vertiginous effect, one that leaves the reader breathless with anticipation for the inevitable splash, as McFarlanecan only fit so much into these panels and must economically revealthesecrets therein.Using these panels forces McFarlane, by choice, to show us only those elements that will best push the story forward. Because of this claustrophobic use of panel layouts, it's almost a relief when he opens up the page a bit more, and we fall into his expertly rendered drawings. He's a master manipulator, like most artists, but we don't mind being manipulated.

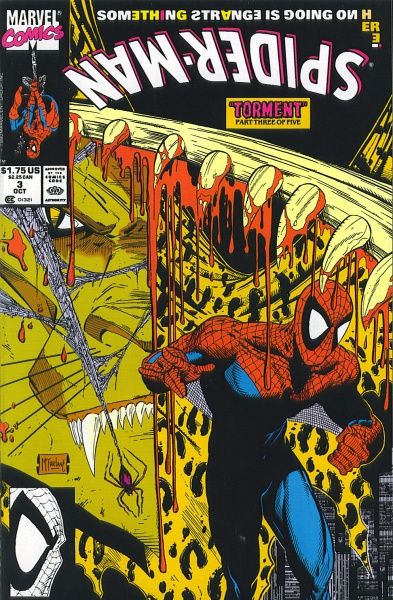

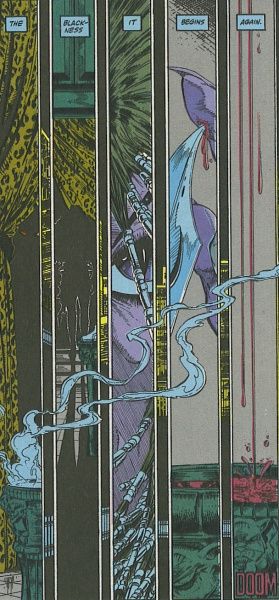

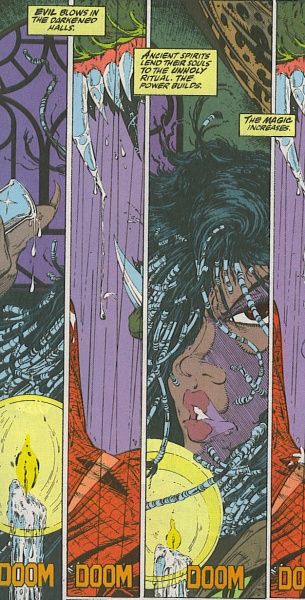

The thin panels also serve to highlight a minor motif running throughout the story, and that is the dripping of liquids. Blood, of course, is the most often featured, but water serves as well.Using the panels to show long strands of liquid flowing from the top to the bottom of the page gives not only a distorted sense of motion (as we read from left to right, and the top-to-bottom flow of the narrative disorients us, which is McFarlane's purpose), but serves as a way to extend the story itself, as the viscous blood seems to flow forever from the heights to the depths (a motif which is mirrored in McFarlane's writing). This lengthening of the story extendsthe reader's torment (in a good way), because Spider-Man is being tortured throughout this arc, and we, the audience, are squirming in our seats along with him. It's an astonishing way to once again make us claustrophobic, setting us up for the breathtaking larger panels.

It is, of course, in the larger panels that McFarlane can flex his artistic muscles, something we see from the first double-page splash, in whichSpidey swings high above the maddening crowd. McFarlane's rendition of Spidey has become iconic and influential, from the eerieness of thetwisted and often superfluous webbing to the gangly way in which Mr. Parker moves. McFarlane's Spider-Man looksspider-ish, which is why his rendition is so brilliant. Mostartists drawSpider-Man as a man in a spider-suit. McFarlane draws him as something a bit darker - a true amalgamation between man and spider. This makes usuncomfortable, although many people don't realize why they're uncomfortable,but it alsoforces us to view our hero in a new way, one thatpresumes what would really happen if an irradiated spider bit a man and granted him spider-like powers. Peter is still human, naturally, but he has becomemore fluid,quicker,and tense. He seems to flit across the pages when McFarlane draws him, much like an arachnid. It's a mesmerizing effect.

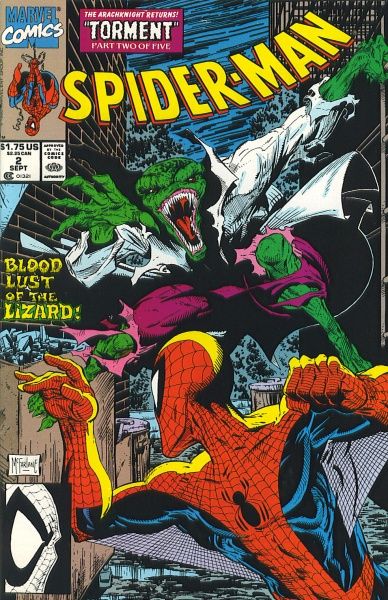

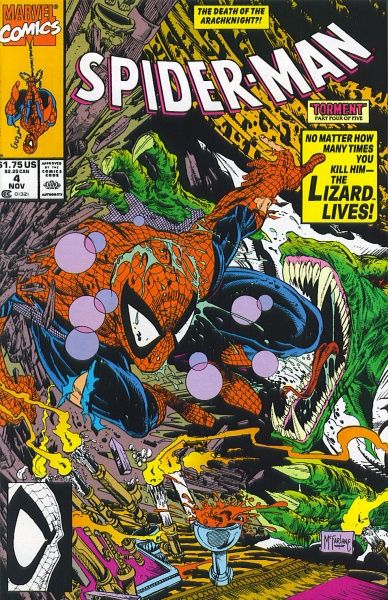

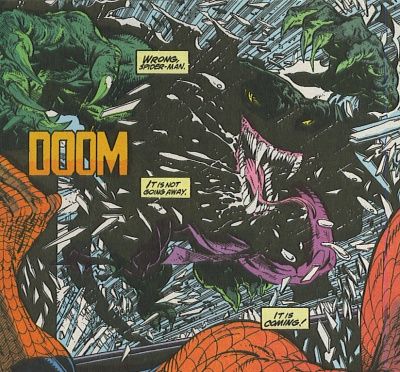

Similarly, the Lizard is a true force of nature, made dumb by Calypso's spells, lost in its reptilian brain, all trace of Curt Connors subverted except for a vague attempt to warn people of its true nature, when it spells part of Connors' name in blood on a wall nearavictim. McFarlane's Lizard is all carnivore, completely inhuman, whichMcFarlane highlights by keeping the Lizard in Connors' customary lab coat and pants. This incongruity helps to show us, more than ever, thatthe Lizard has left Connors behind and succumbed - through nofault of his own, but still. The primal nature of the Lizard, coupled with the Caribbean sexiness of Calypso, makes the villains in this piece asdynamic as the hero, and alsodraws the reader to them. The Lizard appeals to our reptilian urges, and Calypso to our basest desires. Without giving us a reason through his writing (which is brilliant on other levels, as I'll show), McFarlane makes usroot for the bad guys even though we know it's wrong.It's a magnificent achievement.

In the writing is where McFarlane shows that he's not a one-trick pony. The writing is, if possible, even more impressive than the art, because we all knew the art was going to shine, but no one was quite sure what McFarlane would come up with for the script. He doesn't disappoint. On the first page, with the five vertical panels, coming from a cityscape to closeups of the people scuttling along in their sad, pathetic lives, McFarlane writes: "The city. New York. Littered with towering concrete giants that seem to swallow up the sky. They are silent -- frozen -- man-made guardians. Below is where the city's heartbeat is. People scurry about their business. Oblivious to the crowds -- the congestion -- the pressure -- yet -- at times, some wish they could -- Rise above it all!" That last phrase, which is on the second page and introduces the double-page spread with Spider-Man swinging over them, completes this terse, almost Hemingway-esque prose with aplomb. He continues: "His name -- Spider-Man! His powers -- extraordinary! His webline -- advantageous! Below, the people continue to scurry." If we break down those first two pages, we see the genius of McFarlane. He cuts straight to the heart of the story - the city is stoic, unfeeling, harboring nameless, faceless automatons, who cannot see the cancer in their midst. Only Spider-Man, who is able to "rise above it," can see the bigger picture, and only he can save the people from the menace of the Lizard. But McFarlane is employing irony as well: "below is where the city's heartbeat is," indeed. Spidey may appear to have the "advantageous" position because of his ability to fly above, but it's deep in the bowels of the town, where the Lizard and Calypso lurk, where the answers lie. In these two pages, McFarlane brilliantly encapsulates everything we need to for the story, and then he circles back and fills in the blanks.

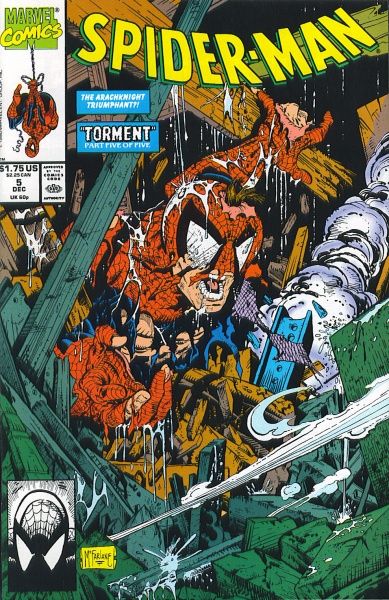

As we get further into the story, McFarlane introduces the Lizard, but keeps Calypso secret, at least for a while. The elements of voodoo in this story, which could be silly in the hands of a lesser writer, work their spell much like McFarlane's panel layouts, creating a sense of dread in the reader that builds with each passing issue.McFarlane creates this tale almost in a sexual way, both with the art, as we've seen, and with the narrative, which continues on this terse, choppy style and the thudding of the voodoo drums until the tension explodes, literally, when Kraven's townhouse is destroyed. This climax, which comes at the end of a frenzied issue #4, leaves us breathless. Earlier, McFarlane had played on both Spidey's and the audience's paranoia when he teased that Kraven had come back to life. It's an illusion, however, brought on by Calypso's poison that is coursing through Spidey's body. Calypso takes him to Kraven's townhouse, where she twists and turns Spider-Man until he doesn't know what is real anymore. McFarlane beautifully links this story to "Kraven's Last Hunt," except that Calypso, unlike Kraven, does not want to prove that she's better than Spider-Man. She just wants to drive Spidey insane. When the townhouse explodes, Peter Parker is caught inside, but of course both he and his foes survive, for a battle in issue #5 that puts all comic book fights to shame. The Lizard is defeated, but Calypso escapes (I'll get to that). Throughout the epic, McFarlane has been repeating the phrase "rise above it all" on each second page, which accompanies a double-page spread. McFarlane cleverly links this to the struggles of Spidey to overcome Calypso's programming, and he ties it back into Peter's attempts to dig out of the grave that Kraven had put him into. Finally, the Lizard succeeds in breaking Calypso's spell, "rising above" the voodoo to once again become the intelligent monster we all know and love.

Throughout the story, McFarlane checks in on Mary Jane, who spendsPeter's horrific night dancing at clubs. It seems a bit incongruent, but what it shows is that their marriagefar stronger than we might expect.MaryJane doesn't need to wait up for Peter, because shehas long ago come to grips with his superhero life. There's no need for her to worry. Showing Mary Jane dancing the night away highlights the torment through whichPeter goes. Her carefree world is what Peter is striving for, and these seemingly dichotomous storylines really show thelife that Peter would lose if he gave in.

The ending of the story really shows whyusing the word"genius" to describe McFarlane would not be too farwrong. In his first attempt at writing, he allows Calypso to escape without ever explaining herself. This is a bold statement, because it shows, once again, that McFarlane isnot bound by the conventions of storytelling, and that he is, in fact, creating a new way of writing a story. When this story ends, we are unsure if Peter himself is insane. Did Calypsosucceed in her plan? When Spider-Man finally returns to his apartment, he croaks, "Honey -- I'm -- home." This attempt at typical Spidey humor is perfect, because it creates doubt in our mind. What sane man, having endured what Peter has, would joke the first time he is able to see hiswife, his lifeline? It's a chilling line, because we wonder about what is really going on in Peter's mind. This, coupled with Calypso's escape,make"Torment" a twisted masterpiece, inMcFarlane's first attempt at writing.

McFarlane continued to dazzle readers with his next two stories, a two-parterwith Hobgoblin and Ghost Rider and a five-parter about a child-killer loose in the British Columbia wilderness that featured the Wendigo and Wolverine. Both are instant classics, but neither get under your skin like "Torment" does. If you only ever get to read one comic story, there's really no question: this is it. It's everything comics should be. We're just lucky someone like Todd McFarlane went into comics instead of some other field, where he might have cured cancer or hammered out a peace settlement between Palestinians and Israelis or fixed global warming. These issues, naturally, are collected in a trade, which is probably the best place to read it.Each individual issue is worth well in excess of $1,000, anda copy of issue #1 with the cool metallic effectcan go for $20,000. I'm just waiting until my kids need to go to college before I sell mine, at which time it might be worth over 50 large. But you know what? They're totally worth it.

Writing any more of theseposts would be pointless, as there are no other Comics You Should Own after you've read these issues, so I strongly suggest you check out the archives. Seriously, read the archives!