I can't imagine you didn't know this was coming!

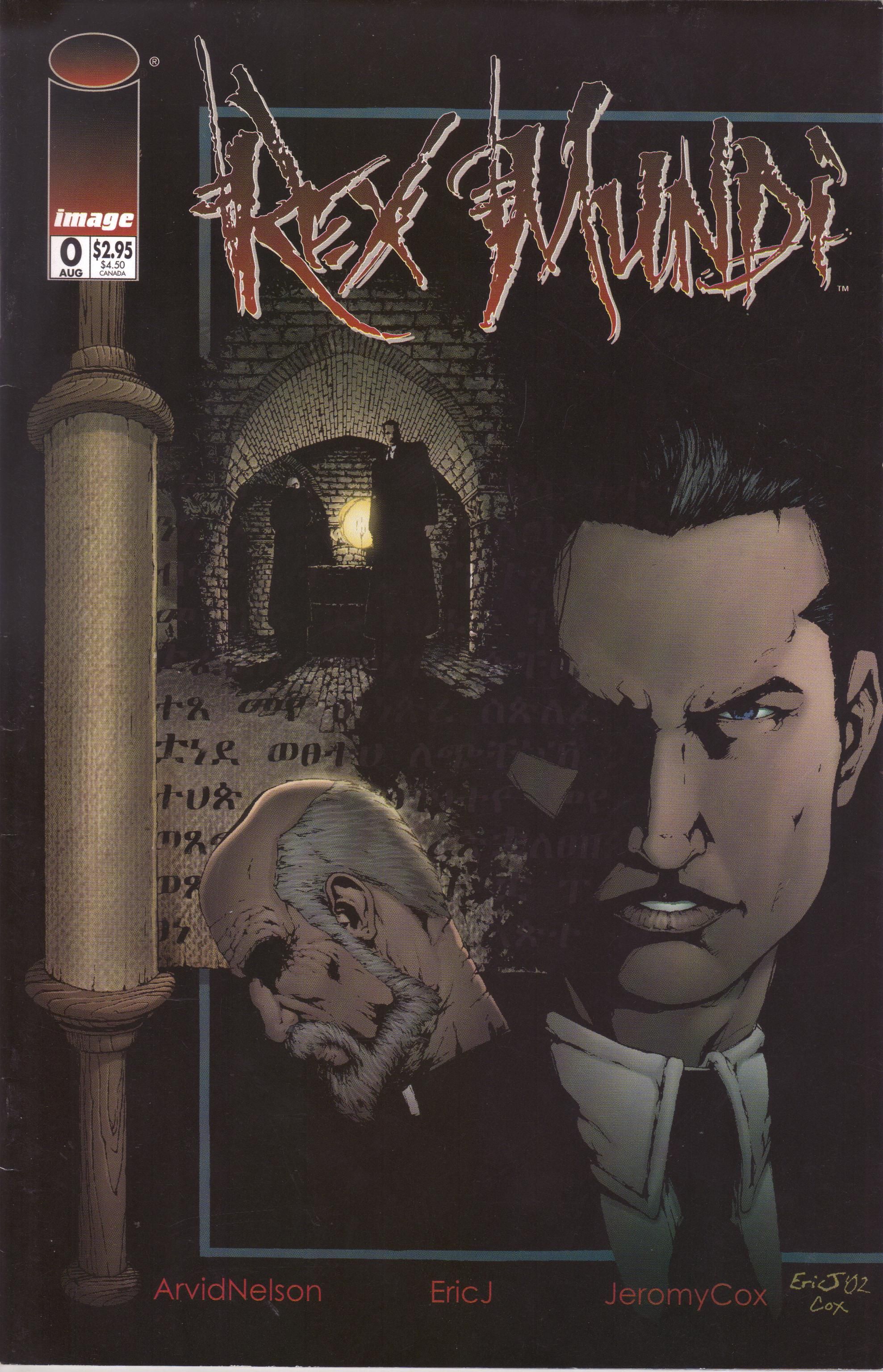

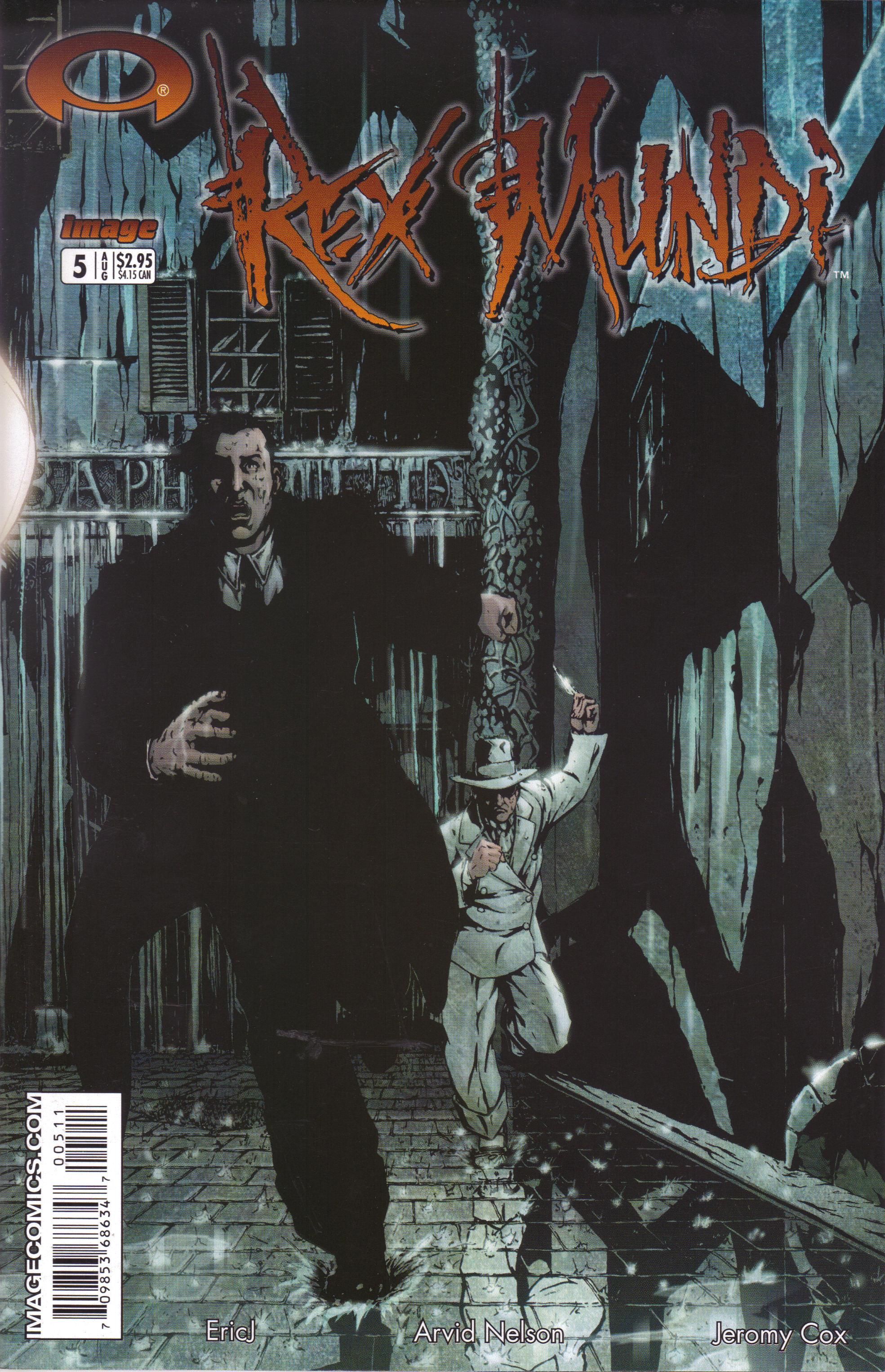

Rex Mundi by Arvid Nelson (writer/letterer), EricJ (artist, issues #0-13), Jim Di Bartolo (artist/colorist, issues #14-15; 6), Juan Ferreyra (artist/colorist, issues #16-18; 1-5, 7-12, 14-19), Guy Davis (artist, issue #13), Brian Churilla (artist, issue #13), Jeromy Cox (colorist, issues #0-13), Dave Stewart (colorist, issue #13), Jason Millet (colorist, issue #13), and François Peneaud (French language consultant, credited in issue #0-13).

Published by Image (issues #0-18) and Dark Horse (issues #1-19), 38 issues, cover dated August 2002 - April 2006 (Image series) and July 2006 - August 2009 (Dark Horse series).

SPOILERS, as usual. Proceed at your own risk! (Although, as always, I do try to keep them to a minimum!)

The somewhat surprising success of Dan Brown's The Da Vinci Code (it's a fairly typical thriller, with short chapters that end on "shocking" cliffhangers, and it's very bad writing, so its success is surprising only in that it rose above hundreds of other thrillers exactly like it) focused attention, however briefly, on the idea of a conspiracy tying several historical strands together and which can be traced back to a book published in 1982 called The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail (American audiences, apparently unable to handle articles and conjunctions, got a version called Holy Blood, Holy Grail). HBHG is a far more entertaining book than Brown's, because it purports to be investigative journalism and historical sleuthing, and it's utterly ridiculous as either. Both books tap into humanity's love of conspiracies, as conspiracies are, weirdly enough, more reassuring than randomness.

It's much more comforting to think that some secret cabal is guiding history to some sort of objective rather than admitting that, most of the time, things aren't connected at all. A conspiracy is at the heart of Rex Mundi, and while it's based on the same kinds of mysteries that both The Da Vinci Code and Holy Blood, Holy Grail delve into, what makes it better than either of those works is that it's clearly fiction and the world in which it's set is more conducive to the conspiracies that, in our world, are more ridiculous the more you consider them. It's all about context, and Arvid Nelson creates a world in Rex Mundi that, while similar to our world, is a place where such vast conspiracies are more believable, even as Nelson slowly leads us away from them to point out how ridiculous they are. By the end of Rex Mundi, the fascinating thing is how ineffective the bad guys really are, even though they seem invincible for much of the book. The comic transforms in the course of its run from a conspiracy thriller to ... something deeper, and that's another reason why it's better than schlocky fiction like Brown's book.

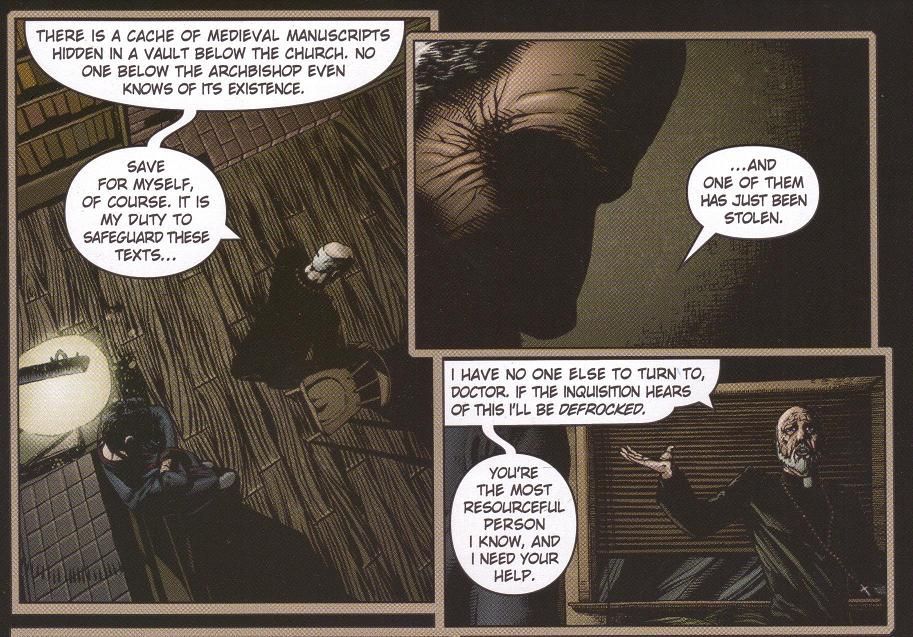

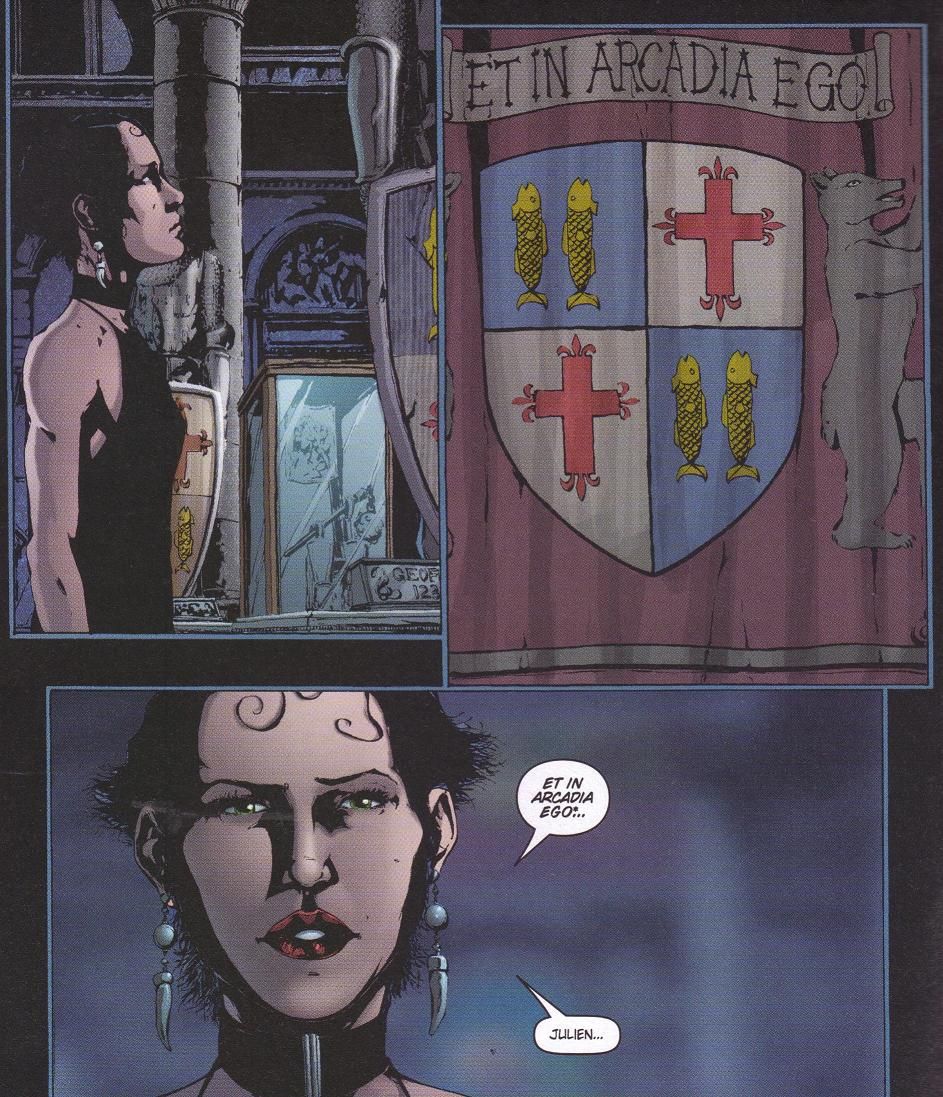

Nelson tends to be a better plotter than scripter, although he's no slouch in either aspect. He had a grand idea for the series, and Rex Mundi was the result. In the zero issue, we're placed in Paris, 1933 (the date is significant for two reasons - Hitler rose to power in reality in 1933, and it's 1900 years after the traditional date of the crucifixion of Jesus) and introduced to Julien Saunèire, an alcoholic doctor, who receives a visitor one night in the form of Father Gérard Marin, a priest in charge of a cache of secret scrolls hidden underneath his church. He's come to Julien because one scroll has been stolen, and Father Marin can't be seen searching all over Paris for it. The scroll isn't a MacGuffin, as we might expect - it is quite crucial to the entire plot. It gives the location of burial sites for the Merovingian kings in southern France, as compiled in the 13th century. Why anyone would want to know that is, of course, part of the mystery.

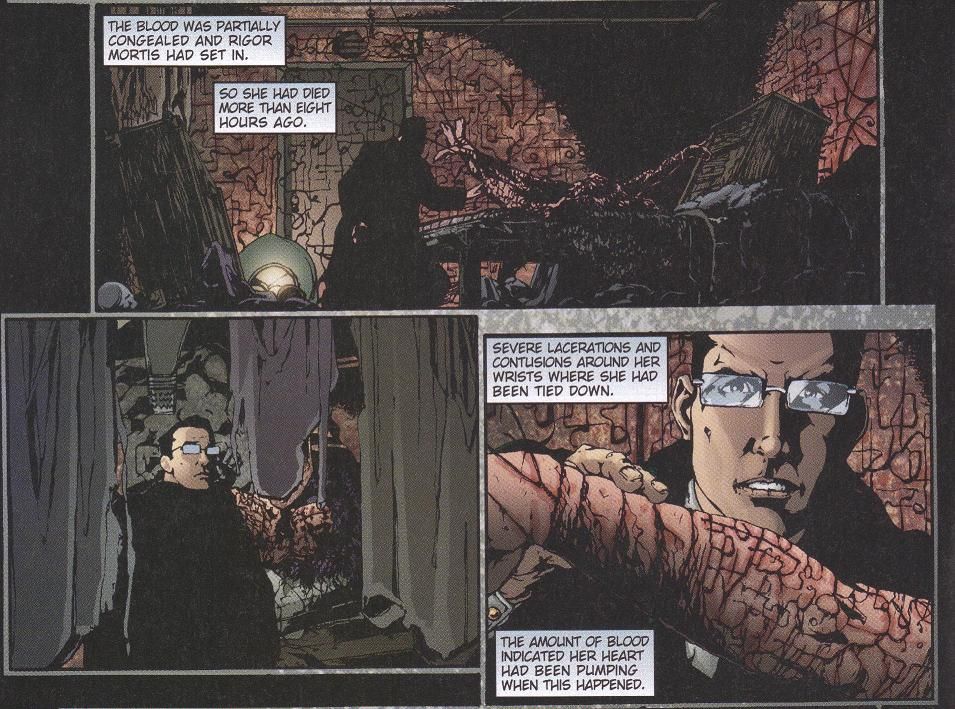

Marin tells Julien that he was having an affair with a prostitute and he told her about the scroll. Julien goes to speak to her, and finds her murdered in a bizarre ritualistic way. An issue later, Father Marin is killed as well. And so Julien is slowly tangled in this mystery.

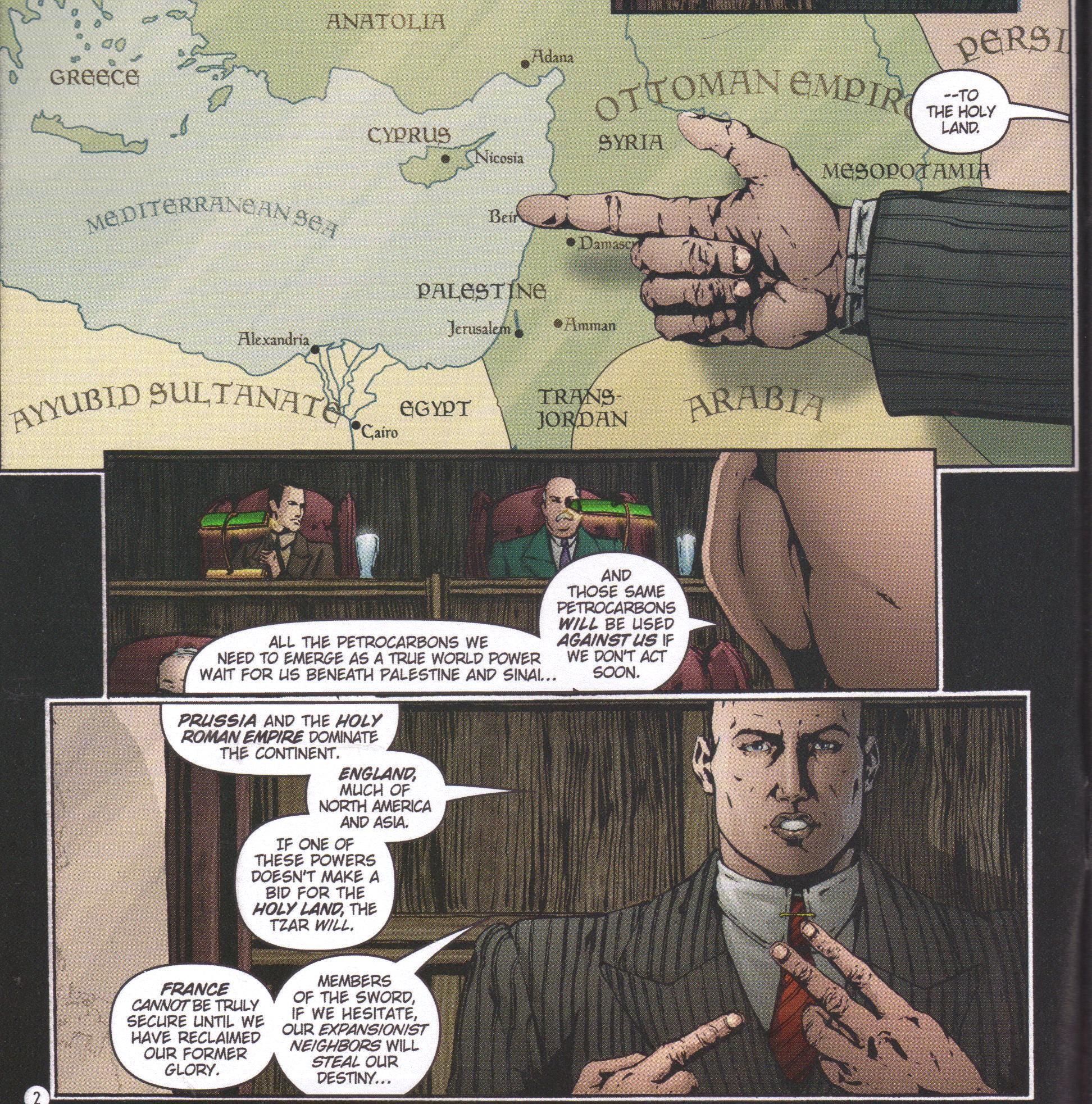

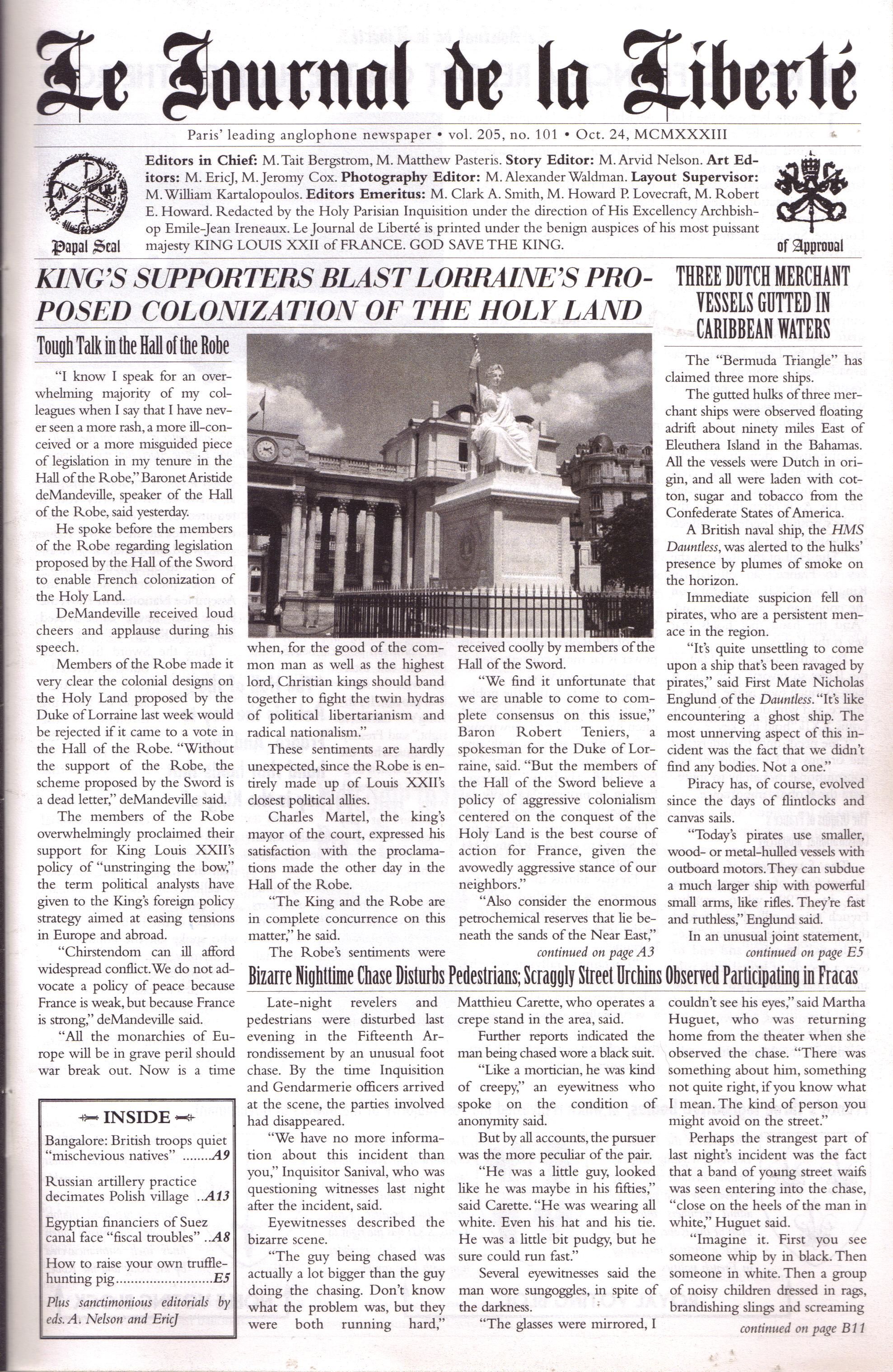

One thing that we learn very quickly is that this world isn't our own, as I mentioned above. Father Marin suspects the thief may have used magic to access the vault where the scrolls are kept, and then, at the end of issue #0, we get the first of many faux newspapers that Nelson and Johnson (he goes by EricJ, but his last name is Johnson, and I like using that more than typing EricJ all the time, so there) created and put in the back of each issue, in which we learn that the Inquisition is still active in 1933 Paris, while Prussia and the Ottoman Empire are still around. This is a world that's still familiar to us, even though it's clear as we go on that World War I never occurred, and nationalism as a concept is just emerging in the 1930s. This means that Nelson can blend events from our world and telescope them nicely - there are clear echoes of the tangling alliances that led the Great Powers to get involved in a world war over a minor territorial dispute in 1914, but the Duke of Lorraine's rise to power clearly aligns with Hitler's. Nelson does a nice job implying that history, by and large, follows similar paths even in "alternate" worlds - Rex Mundi is a grand example of what historians call a "counterfactual," by which they mean a small change in our actual history leading to different results. In the world of Rex Mundi, these counterfactuals are always happening, and it's unclear where this world diverged from our own. The French Revolution occurred but was stifled by Royalists before Napoleon could seize power (Napoleon is stated as dying in a prison cell, largely unknown), but the divergence seems to be even before that. There was a Protestant movement, but it's unclear how strong it was, and it does seem that Catholicism remains dominant. Nelson has a lot of fun with the world - he extrapolates out from many key points in history, so in this world, George McClellan defeated Abraham Lincoln in the election of 1864 (a very real possibility) and sued for peace, dividing the American continent between the North (the Federal Republic of America) and the South (the Confederate States of America) and permanently weakening both.

As there was never a First World War, the ruling houses of Europe - the Habsburgs, the Hollenzollerns, the Romanovs - are all still in power, as is the Ottoman sultan. Curiously, the Christians never reconquered Spain, which is still ruled by the Cordovan Caliphate. This is a key point in the book, as the Duke of Lorraine comes to power partly because he promises to drive the Muslims from Europe. Nelson does make a few mistakes in his history, which isn't surprising considering everything he's juggling and doesn't really detract from the quality of the work. His most egregious is perhaps beginning the book with Emperor Karl-Josef as the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, which at this point in our world was Austria-Hungary. Karl-Josef was, in fact, the last emperor of Austria in our world before the empire was dissolved at the end of World War I, but he died in 1922. He's the emperor in Rex Mundi until issue #10, when Nelson switches the name of the emperor to Rudolf, who would have been the emperor had he not killed himself (or been murdered?) in 1889. In Nelson's world, Rudolf became emperor in 1906 on the abdication of his father, Franz-Josef. Why did Nelson switch the emperor? It's possible that Rudolf, as a more romantic figure (the official story is that he killed his mistress and then himself because he couldn't deal with the strictures of court life anymore), fit more into the world of Rex Mundi. It doesn't matter too much, but it does stand out slightly.

The other mistake Nelson makes regards the actual mystery, and once again, it's not too big a deal. Father Marin claims that the scroll leads to the tomb of Clovis II, the "third monarch of the Merovingian dynasty." He means Clovis I, who ruled the area now known as France from AD 481-511 and is regarded as the greatest Merovingian. That's a minor but annoying mistake, but Nelson is at least consistent with it. What strikes me as odd is that Julien has never heard of Clovis, which seems impossible. Clovis, through the influence of his wife, Clotilde, made Catholicism the state religion of the Frankish realm, and is still venerated in France today. His name, Frenchified, is "Louis," for crying out loud. A Frenchman of Julien's education would have known a great deal about Clovis. I get that Nelson wanted to give the reader information about Clovis through Julien learning about him, but that detail bugged me when I read this comic.

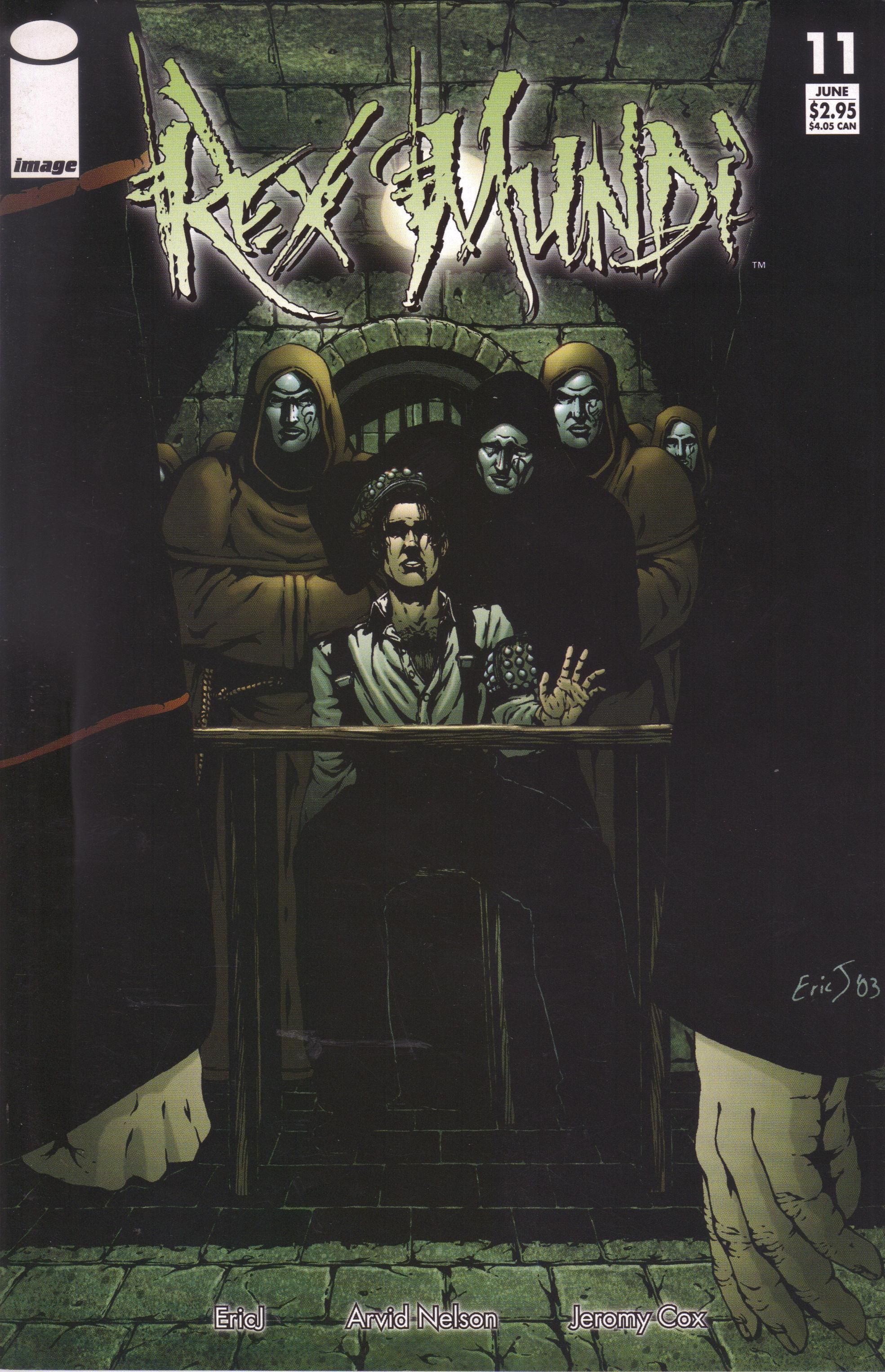

Anyway, the plot is almost always paramount in Rex Mundi, even though Nelson does, over the course of the series, give the main characters a lot of personality. We quickly meet the principals: In a short back-up story in issue #0, Nelson introduces the Grand Inquisitor, Moricant (although his name is different in this initial story), but he gets a proper introduction in issue #2.

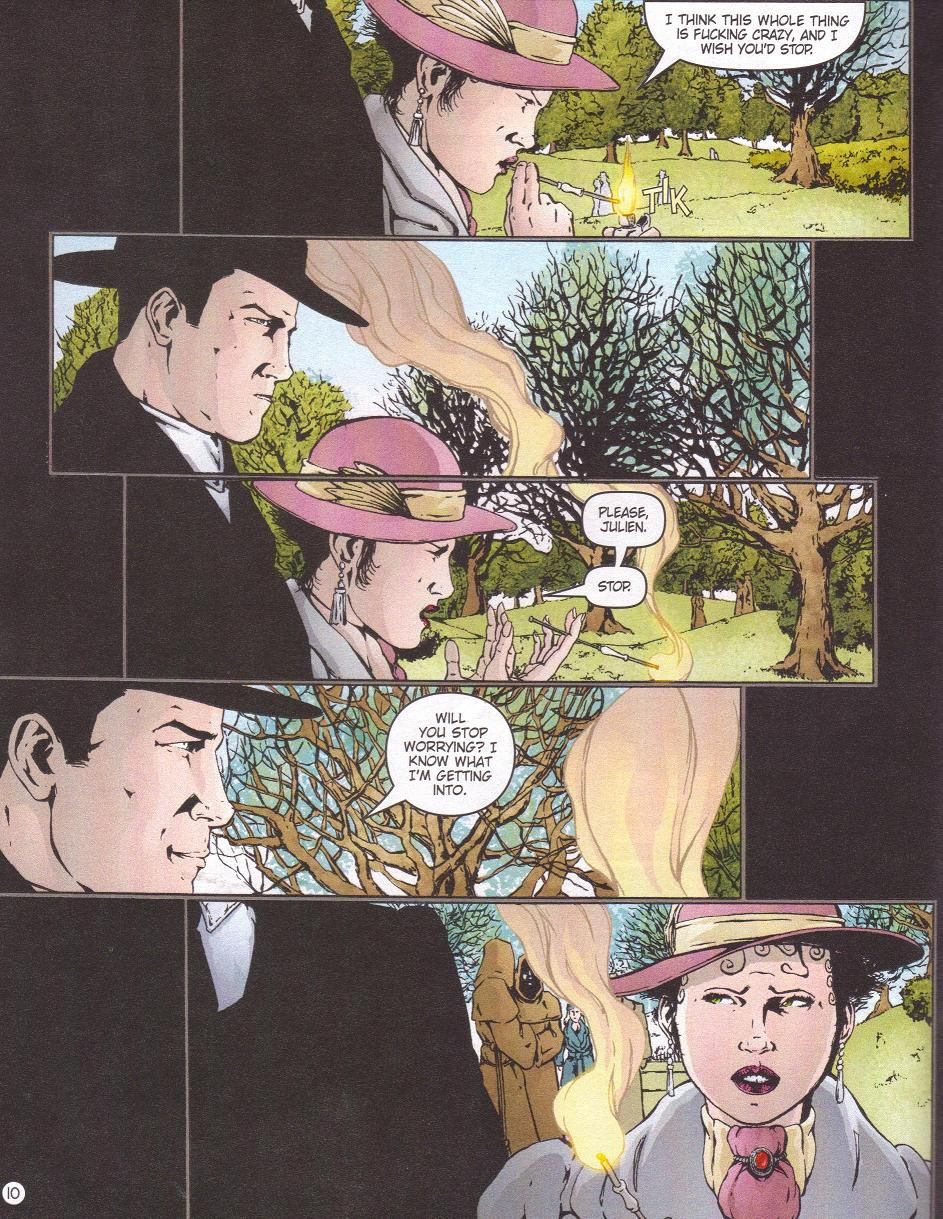

He becomes far more important much later in the series, but early on, he seems to be just a thug who works for the Church. Also in issue #2, Genevieve Touron enters the book. She's an ex-lover of Julien's, and we learn two important things in her first appearance - she is the Duke of Lorraine's new court physician, and she's about to gain a seat on the High Council of France's guilds, an extremely powerful position. The duke himself - David-Louis Plantard de Saint Clair - shows up in issue #3, making a speech before the Hall of the Sword, one of the legislative bodies in French politics. Lorraine is already sowing the seeds of his empire by claiming that France needs to establish themselves in the Middle East because of all the "petrocarbons" under the soil. Lorraine is attended by the obsequious Baron Teniers, who will also play a greater role in the latter stages of the book. Issue #3 also brings us Archbishop Ireneaux, who initially warns Julien off the case before eventually enlisting him (in issue #11) to help the Church find what the scroll leads them to. Finally, in issue #5, we first meet Isabelle, Lorraine's only child, who is also far more important later in the book. It's interesting how Nelson works all of these people into the story early enough so that nothing seems like a MacGuffin, even the inciting event. Even though people like Isabelle and Brother Moricant disappear for long stretches of the comic, when they do reappear, we already know who they are and accept their presence. It helps hold the book together much more tightly than we might expect.

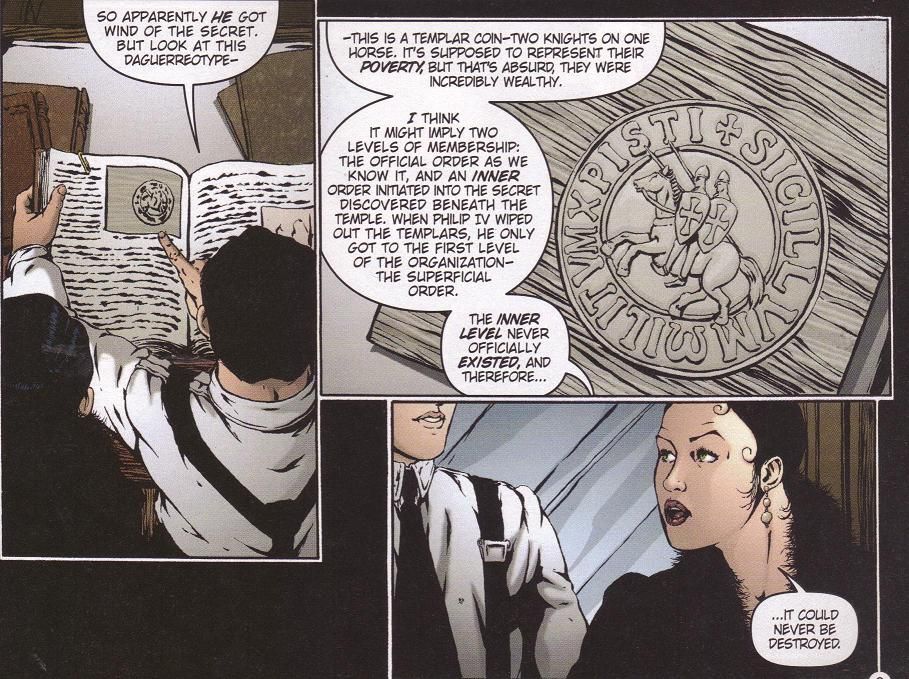

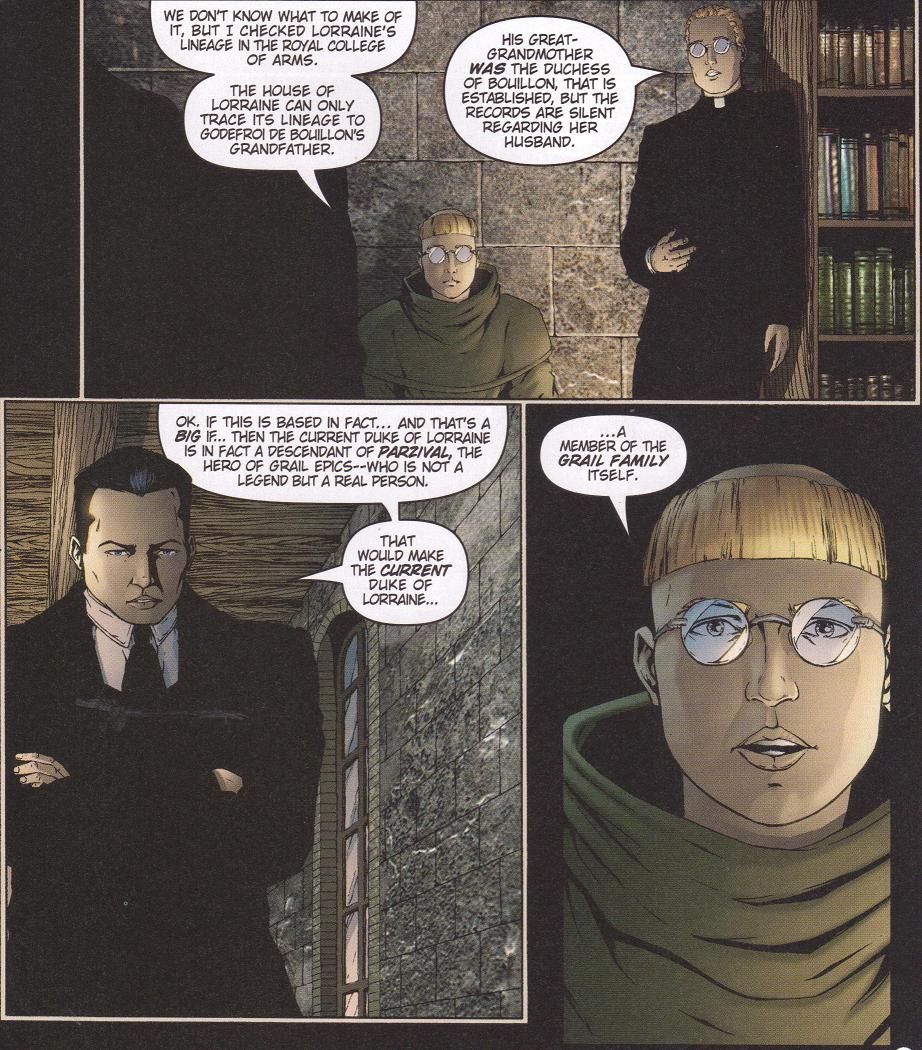

The plot gives us the main outlines of the so-called secret: the bloodline of Jesus; the Merovingians as inheritors of that bloodline and their betrayal by the Church; the Crusades and the Templars and their strange behavior; the Albigensian Crusade in the Languedoc against the Cathars; the suppression of the Temple by King Philip le Bel and Pope Clement V; the Priory of Sion; Nicholas Poussin; even the Fronde and other unusual events in French history. The Duke of Lorraine is the heir to the bloodline, and this makes Nelson's fictional telling of the story more compelling than the version in our world (which is as fictional but has often been claimed as true), because Lorraine is in a position to exercise political power, unlike the Plantards and St. Clairs in France today. As he points out, he really is the King of Jerusalem, in political theory, fact, and in genetics, so his speech in issue #3 about how France needs to launch a modern-day Crusade to the Holy Land is both practical politics and his attempt to retake his ancestral home. Because Nelson sets this in an alternate reality, the abstraction of these secret societies and their manipulations of politics can become something more tangible and frightening. Nelson makes us believe that a 1900-year conspiracy could actually exist in this world, which is perhaps his most impressive feat.

The plot isn't the only thing that works in the book, however. Nelson manages to create a world that is so like ours that he's able to comment on things in our world without breaking too much from the narrative.

In the newspaper in the back of each issue, he is able to give us events in this world that either we've already experienced but are reading about from a different point of view or events that the main characters know nothing about. In a few instances, Nelson goes too far with this conceit and puts in news items about modern celebrities, thinly disguised to fit into 1930s Parisian society, but he gives that up fairly quickly. In issue #9 (February 2004), he adds a "society page" to the newspaper, and includes articles about "Brittany Feuillère," who wants an annulment after a hasty wedding (perhaps a double reference to Edwige Feuillère, a French actress of the 1930s?); "Paris Huguet-Renoir," a hotel-and-casino heiress who was filmed having sex; and "Janet Témerson," who bared her breast at a performance during the Rugby World Championships. There's more of this in issue #11, but then Nelson abandons it, which was a good call, because the newspapers are important in helping create this world, and references to "Jacques Gittes" take the reader right out of it. Overall, though, he's able to show us a Europe that's familiar but different, which makes it easier to accept some of the stranger things that happen in the series, like the use of magic and the appearance of a griffin. This also allows him to bring up interesting themes that still have an impact in today's world. While the obvious tabloid exploits of celebrities don't work, the way Nelson works in these themes does, and it makes Rex Mundi much more than just an adventure thriller.

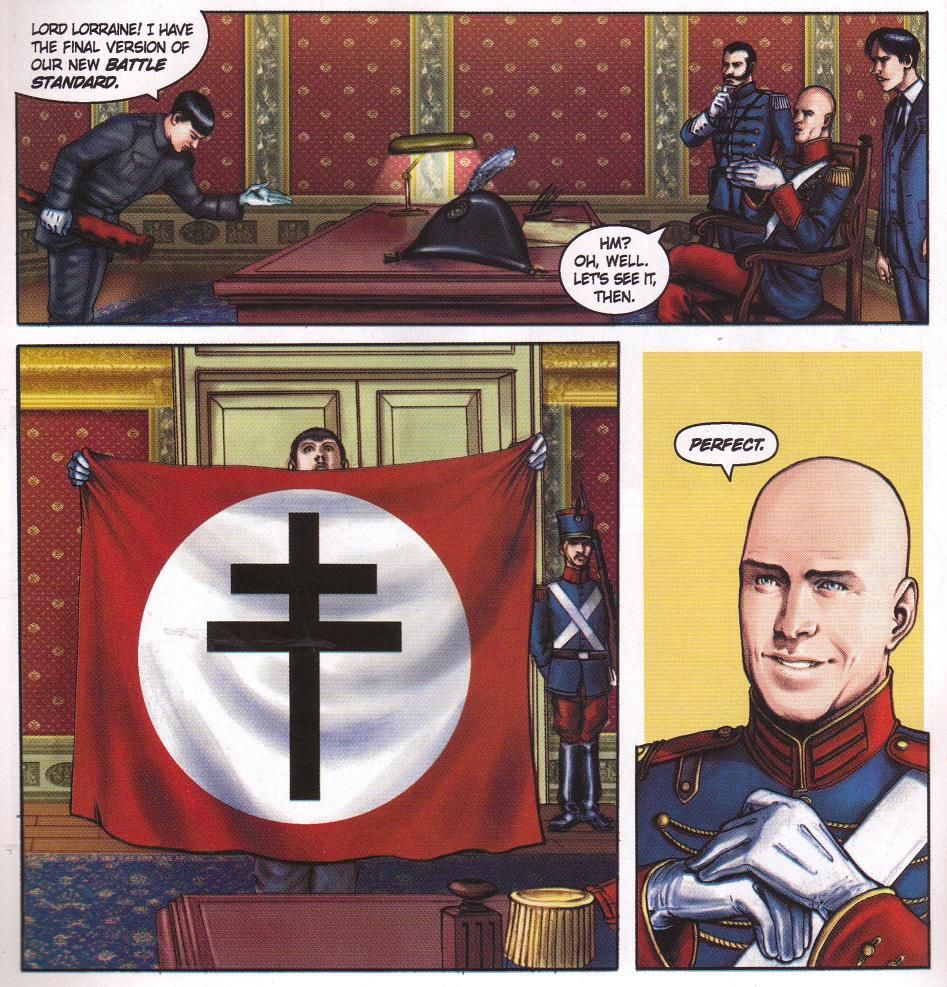

Obviously, the most prevalent theme is that of fascism and what needs to be in place for it to rise. Nelson certainly doesn't attempt to explain Hitler in this comic, but Hitler wasn't the only fascist around, and in the Duke of Lorraine, we get an antagonist whose journey toward a more Hitlerian reality is fascinating.

Lorraine seems like an ambitious politician at the beginning of the book, but as he becomes more and more convinced that his bloodline is the only one that can save France, he becomes more and more unhinged. He goes from using his bloodline cynically to believing it completely, so much so that toward the end of the book, his generals are beginning to think it would be better if someone less insane were in charge. Nelson gives us a good reason for Lorraine's belief - he is, after all, descended from Jesus - but his ramblings become increasingly Nazi-like as the book goes on, and Nelson then shows why his beliefs are so ridiculous after all. This parallels Hitler's ideas without trying to explain Hitler's insanity - Lorraine is a very different kind of person than the Führer, so even when Nelson makes the connections obvious - Lorraine's flag looks very much like a Nazi one - we are able to understand the differences between them. Nelson is able to show the way a man could go too far without trying to say, "This is why an actual historical monster did," and it's a good choice. The idea of religion and whether its adherents are evil is a prevalent theme, too. Nelson and Johnson started working on this before 11 September 2001, but it didn't show up until after that day, so when Lorraine speaks of Islam overwhelming Christendom, we hear the parallels in our own world. In Lorraine's case, he's speaking of the Ottomans seizing all the oil reserves in the Middle East and the Emirate of Cordova in the Iberian Peninsula, but the spirit of the remarks is the same. Early on in the series, Julien visits a rabbi for help with Father Marin's murder, and that allows Nelson to show how medieval the lives of Jews in France remains even in the "modern" era. The idea of ghettos is older than Nazism, of course, and we see how little life has changed for the Jewish portion of the population even after hundreds of years. This is in contrast to the real world, where Jews had gained a measure of control over their circumstances in the early 20th century, which was one reason the Holocaust was so shocking. Nelson doesn't "normalize" the lives of Jews in the world of Rex Mundi, which allows the readers to see the fine margin in which they lived. Similarly, in the second half of the book Julien comes across a small community of Muslims in Catalonia, and Nelson does a nice job showing how they exist on the whims of the ruling Christians but also how ingrained they've become in the fabric of the world. Much like how the murder of people who had lived in countries for hundreds of years is shocking, the fact that the Muslims that Julien finds are as European as their rulers but are considered outsiders is surprising. Nelson has pointed out that the Iberian Peninsula in his world is very much like the Balkan Peninsula in our world (there's a Sarajevo moment in this series, but it takes place in Zaragoza, in Aragon), and that includes the presence of Muslims who have been there for centuries but are still considered strangers.

As he does with the idea of Lorraine's bloodline, Nelson cleverly upends the idea that the Christians are somehow better than the Muslims when both religions are filled with good and evil people. That he does all of this fairly deftly in the course of the narrative is nice, as well.

At the heart of it all is the murder mystery, from which Nelson never strays too far. Julien figures out that the prostitute who got the secret out of Father Marin was placed with the priest just to do that, and he follows her trail to discover her pimp and then the man who hired the pimp. He eventually finds the scroll, which leads him further into the mystery of the Templars and their treasure. Whenever we think Nelson is going to forget about the murder, he returns to it, so the book always remains a human drama even as war engulfs Europe. One clue leads to another, until Julien is forced to head for the south of France, where the Templars and Cathars had their strongholds. Without going too much into the particulars of the plot (which, in broad terms, is what you can find in many other books), Julien discovers that he's really trying to find the Holy Grail, and when he finds it, it's not really what he was expecting. Nelson, again, is able to fabricate history where it suits him, but the fact that this is fiction mitigates that. Obviously, Father Marin's murder is only a small part of the grand scheme, but it's still nice how Nelson manages to keep the mystery from spinning out of control, which would have been easy. The book becomes a confrontation between good and evil, which isn't surprising, but how we get there is very interesting and the way Nelson resolves it is well done. Yes, there's revenge and "this ends here!" posturing and every main character getting their big moment, but because it's been set up so well, the reader doesn't really mind it too much.

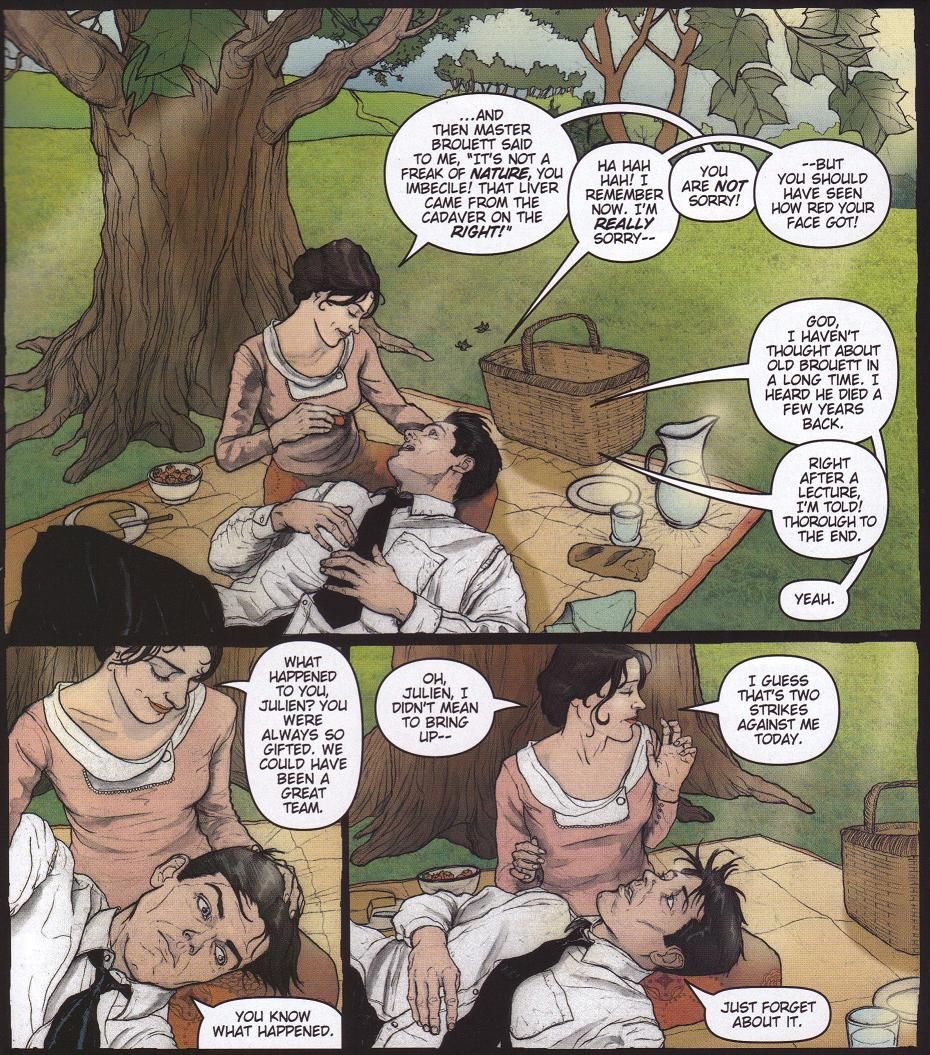

Part of the reason why the plot works so well is because Nelson comes up with such good characters. Julien is the main protagonist, of course, and Nelson makes him a fascinating and flawed hero.

He's an alcoholic but Nelson rarely mentions that too much, simply alluding to it early in the book and then bringing it back when he's at his lowest. As the final act of the book revolves around wine, his affliction becomes more important as we go along. He's not a terribly strong man, cracking easily under torture at one point, and he's not always noble, treating Genevieve poorly after she betrays him even though it's obvious she's repentant. Julien's flaws, however, make his strengths more interesting. He cares about the poor and the outcast - he ministers to the street kids who come to his clinic and can't pay him, and he's the only physician in Paris who will treat the Jews. There's a good reason for this, but just because Julien can do it doesn't mean he has to. As the book moves along, he becomes tougher, but he never really wants to be involved in Lorraine's power play, he's just trying to figure out why Father Marin had to die. This stubbornness helps him through some of the worst times, but it also means he can't understand why the Muslims who help him still retain their faith. Even when he's forced to fight, he often wins less by skill than by luck. Nelson makes him a cerebral hero, but that means he's not the best person to rely on when the good guys need someone to fight. Genevieve is a different character altogether. She's tough as nails, and she has worked her way to the highest level of her profession by sheer force of will. She comes from poverty, and she shows a fairly typical disdain for the poor, those who couldn't make it out of their situations when she did. Her ambition makes her act rashly occasionally, but she's always able to charm her way out of potentially sticky situations. Nelson does a nice job with her, because we know early on that she's reporting back to Lorraine about Julien's movements, but we're never quite sure if and when she'll turn on Lorraine and become a "good guy." Julien makes the point during an early conversation that politics is dominated by men and she needs to be careful, and Nelson does a very nice job showing how precarious her position is because she's a woman. Ultimately, she's a noble character, but she has to overcome a great deal to get there. Julien has an easier road - he makes a promise to an old friend, and that's it. Genevieve has to worry about not only losing her life but the kind of life she's struggled to gain, and while that makes her a bit less sympathetic over the course of the book, it also makes her more interesting. Isabelle, Lorraine's daughter, is another main character. Early on, she doesn't appear too often, and Nelson shows her as a spoiled brat who will have sex with anything with a penis. As the series moves on, Nelson reveals that her mother died when she was six and that Lorraine has very little time for her, and her hatred of him drives her actions.

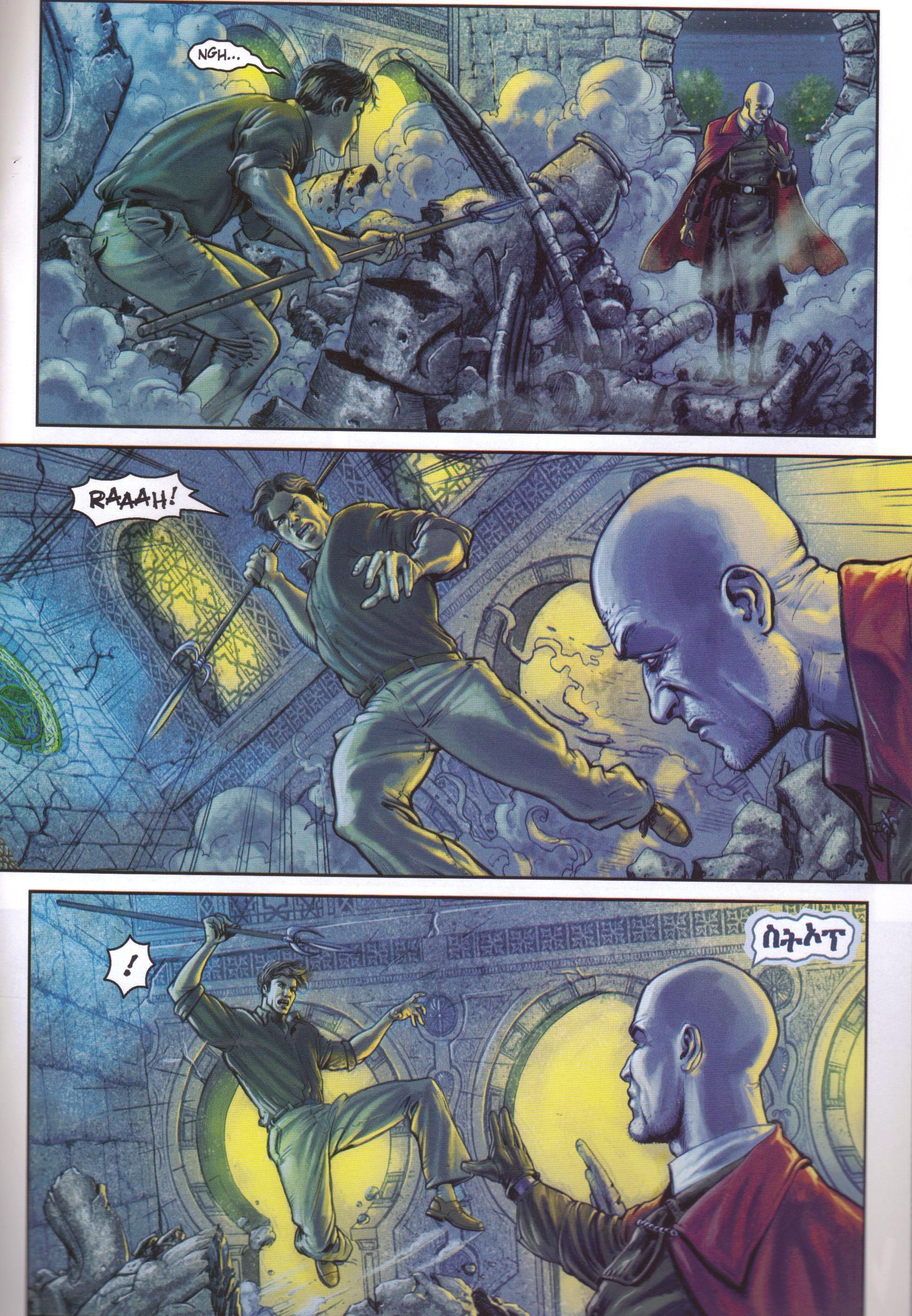

She's a tragic character because her hatred consumes her more and more over the course of the series, but she does serve a purpose, and she softens a bit once she sees that not everyone is evil like her father. Finally, Brother Moricant, the Inquisitor, exists to show the difference between religion and faith. He starts the book as a rigid dogmatic, but once he experiences the secrets of the Grail and the kindness of Christians who aren't tainted by the Church hierarchy and the Muslims in Catalonia, he begins to change his ideas. He symbolizes the major shift in the bigger theme of the bloodline of Christ and how it's changed by the end of the book, and Nelson does a nice job with him.

Nelson had two different but good artists working with him for most of the run (Jim Di Bartolo became the "regular" artist on issue #14 but lasted only two issues), and the look of the comic helps it immensely. Johnson has a much more "1990s Image" style with some over-rendering and filtering that always seems to affect the skin tones of the characters more than anything. He does a good job establishing the tone of the early issues of the series, as he and Cox make the book very Gothic, which befits the murder mystery theme that Nelson establishes. Johnson's figure work is a bit odd - his characters have longer legs than seems normal - but he does a wonderful job with period clothing and styles; Genevieve, for instance, has beautiful curlicues in her flapper-cut hair, looking very much like a mod from the 1930s. She's always dressed to the nines, whether in furs or stylish evening gowns, and Johnson's men reflect well the social strata in which they move - Lorraine and his ilk are higher-class than Julien, so their clothing is a bit fancier than his, while his suits look more utilitarian. Johnson's Paris is richly detailed, as he gives us a strong sense of place no matter where the action takes Julien and the others. Johnson incorporates a lot of photo-referencing into the book - the first page of the comic shows Notre Dame, and it's obviously from a photo reference - but he does a very good job blending it in with the more traditional pencil-and-ink work.

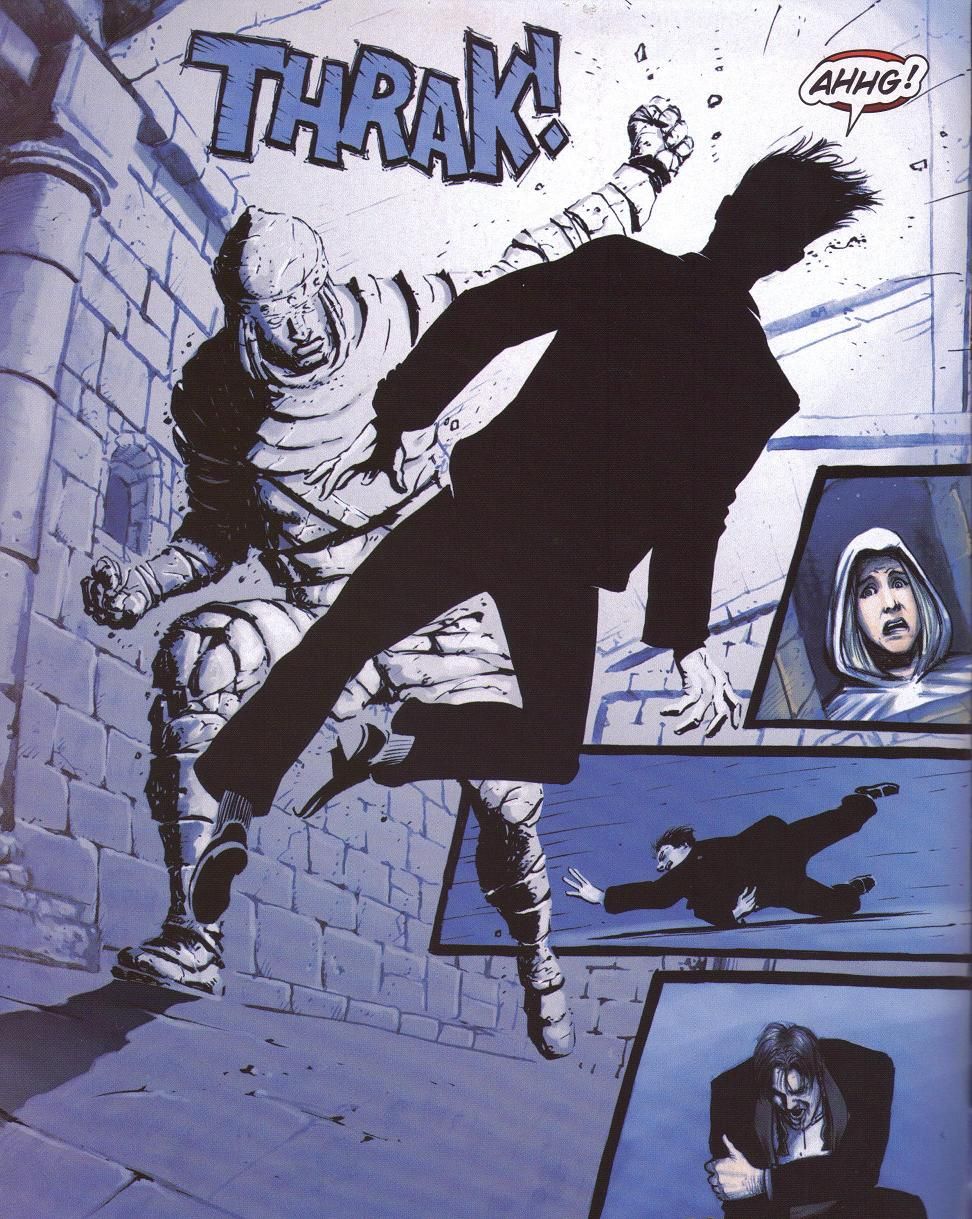

Johnson's weakness, at least in this comic, is dynamic action scenes, and during his run on the book, he didn't have to draw many of those. The book moved beyond its eerie roots and became more of an action/adventure epic, but by then, Johnson wasn't drawing the comic anymore.

Johnson was the co-creator with Nelson, but after issue #13 of the Image series, he was replaced by Di Bartolo. The reasons for the split between he and Nelson are a bit obscure (perhaps the creators would be more forthcoming now, as it's been 7 years since the break-up), but in the backmatter of issue #13, they both seem amicable, although Johnson does seem a bit disappointed that he's not going to be drawing the book anymore. I don't know if it was simply the fact that Johnson seemed to be behind schedule so often - the 14 issues did take almost 3 years to come out, after all - and Nelson had had enough. Once Ferreyra became the regular artist, the final 22 issues came out in a bit over 4 years, so it's not like the book became a model of speed, and maybe the split was just for different reasons. It's interesting to note that the first issue without Johnson features a fairly kinetic gun fight, and I wonder if Johnson would have been able to draw it well or not. It's strange, though, because in issue #15 (Di Bartolo's second and final issue as "regular" artist, although he did art for one more issue later), Nelson moves the action from a small scale (Father Marin's murder and Lorraine's rhetoric) to a larger scale (in the issue, the French Parliament votes to annex the Spanish Marches, one of the marquises is assassinated, and the gears of war begin grinding), and Ferreyra comes on board just in time for a monster to attack in issue #17 and the war to start in issue #1 of the Dark Horse iteration.

I'm not sure if Johnson could have drawn the second half of the series as well as Ferreyra does, and I also don't know if Nelson parted ways with Johnson because he knew this.

Ferreyra's art is different from Johnson's - he uses a much softer line than Johnson and it appears some of it, at least, is colored directly from the pencils. Ferreyra is a fine colorist, too, and the book becomes much lighter when he comes on board (actually, it began to lighten up when Di Bartolo colored his own art in issue #14), but that might be because of the tone of the book as well (Cox certainly could have made the book lighter, but while he was on the book, a lot of the action occurred at night or underground, so he didn't have as many opportunities). Ferreyra's characters are softer than Johnson's - he doesn't use as many inking lines, and he seems to wash the art more than Johnson did. While Ferreyra dresses the characters in 1930s garb, Johnson seemed to be better at making the book feel more like it was set in the 1930s, from the hair styles to the clothing. In Ferreyra's case, Nelson started moving the action away from the Parisian cultural scene to the countryside in the south of France, where style doesn't matter as much. Plus, Lorraine and his cohorts began wearing military uniforms, so of course they looked less stylish. It's an interesting shift in tone in the book - it becomes less of a Gothic mystery and more of an action book, and both artists are suited well to their sections of the comic.

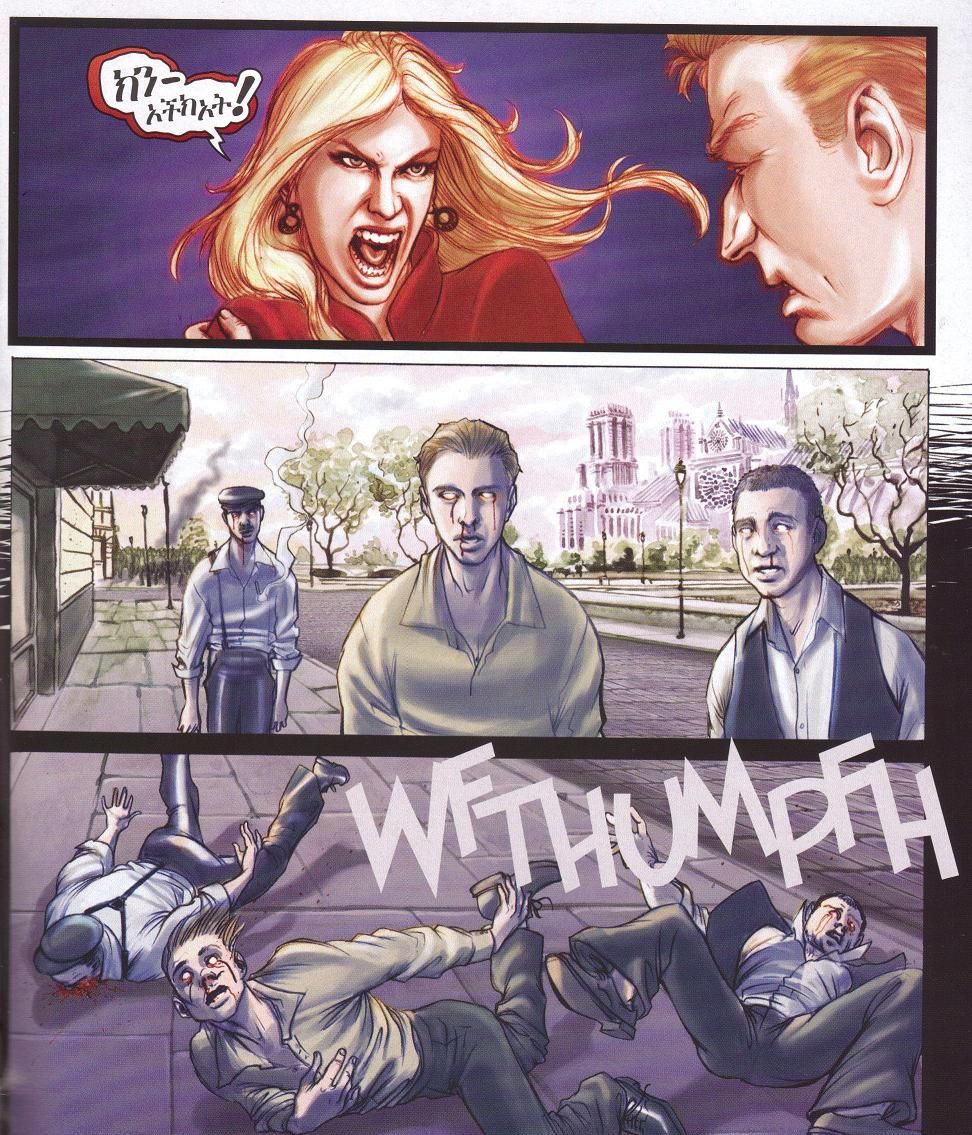

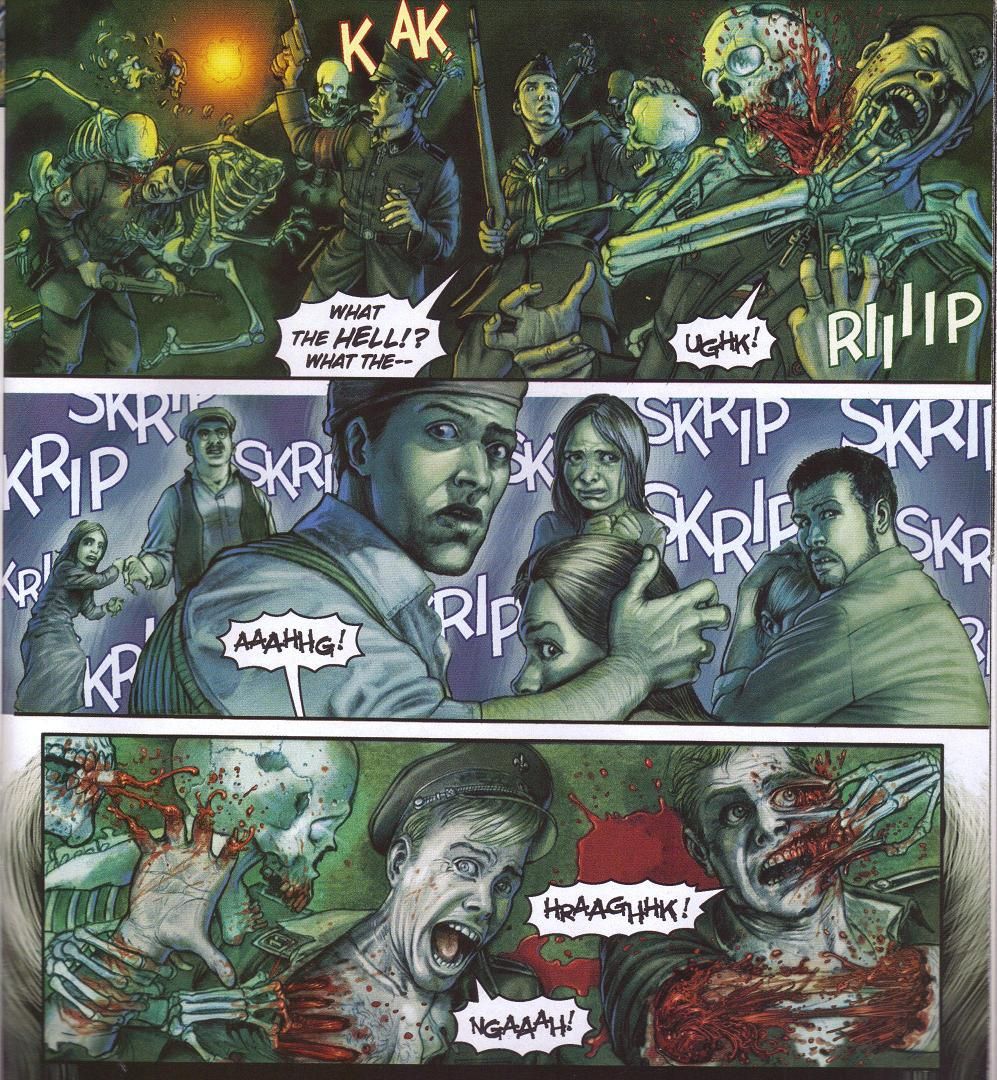

Ferreyra's work is a bit more fluid than Johnson's, so he's able to bring a fine sense of motion to the action scenes that proliferate later in the book. As the series moves into its final phase (issues #8-19), Ferreyra is called upon to draw more violence and action than before, and he does a wonderful job with it. The confrontations at the Grail Castle are horrifying and dynamic and exquisitely detailed, and Ferreyra does a superb job showing how brutal the events are and how monstrous some of the characters have become.

Nelson doesn't make this too explicit in his writing, instead letting Ferreyra show us, especially when it comes to Isabelle and her father, who are on a fatal collision course throughout most of the second half of the book. Ferreyra is amazing at depicting both the opulence of Lorraine's short-lived empire and the horror on which it is built. Nelson doesn't push the old cliché of "paradise built on the bones of the dead" too overtly, but it's there, mostly through the way Ferreyra contrasts the decadence of the ruling French and the destitution of their oppressed subjects in Catalonia. We expect it because that's the way the world works, but it's nice that Nelson allows Ferreyra to make the point rather than doing it himself.

Of course, Ferreyra's pencil work wouldn't be as stunning without his colors, which is where the book really takes a leap artistically in its second half. Cox is a fine colorist in his own right, but Ferreyra's coloring is some of the best you're going to see in recent memory. It's good enough early on in his run, when he eschews holding lines in some drawings and bathes the pencils in stark white to highlight the action (see the scene with the the monster above, for instance, which issue also features some clever border panels when the characters are in the Plantard family chapel), but when the book moves to Dark Horse, Ferreyra really comes into his own. He uses primary colors like red, blue, and green to marvelous effect - Lorraine and his military use bright red and blue to imply their power and strength, for instance. As the action moves south, Ferreyra begins to use blue more often, from the glowing pomegranates in the Grail valley to the magic the principals employ in their fighting, and the comic becomes even more otherworldly as Nelson becomes more concerned with the esoteric. The brightness of the pomegranate wine and other magical things is contrasted nicely with the dull red of the blood the characters shed, and when the book brings in some horror tropes, Ferreyra tinges them with green to make them more eerie than they would be otherwise.

Ferreyra's final few issues are wonderfully drawn and beautifully colored, with the final epic battle a masterpiece of action and brutality. It's breathtaking.

Rex Mundi has been released in six trade paperbacks in at least two different formats - the Image trades and then the Dark Horse trades, which reprinted the Image ones and the Dark Horse series in a standard trade dress. Recently Dark Horse solicited an Omnibus for what I can only assume is the "Image" half of the series, with a second Omnibus presumably collecting the "Dark Horse" issues. Dark Horse's Omnibuses tend to be smaller in dimensions than regular issues, so I don't know how the series will look in that format, but I wonder if the "regular" trades are out of print, necessitating this new format. I also don't know if the faux newspapers in the back of the issues are reprinted, because they do add quite a bit to the reading experience and it would be annoying if they weren't in the trades. For some reason, Nelson and Ferreyra have a new Rex Mundi story in an upcoming issue of Dark Horse Presents, and I honestly have no idea what they could possibly write about, but you know I'll be eager to read it! Rex Mundi is an exciting, fascinating story that takes many interesting turns as Nelson takes it where he wants it to go, and it's far deeper than we might expect, as Nelson delves into everything from faith to political extremism. It's a beautiful-looking book, and it's always a thrilling read even if you're not that interested in Nelson's more philosophical ideas. I hope the Omnibus introduces new readers to one of the best comics of the first decade of the 21st century.

There are always a bunch of fascinating comics in the archives, you know! Give them a look!