It's Walt Simonson - duh!

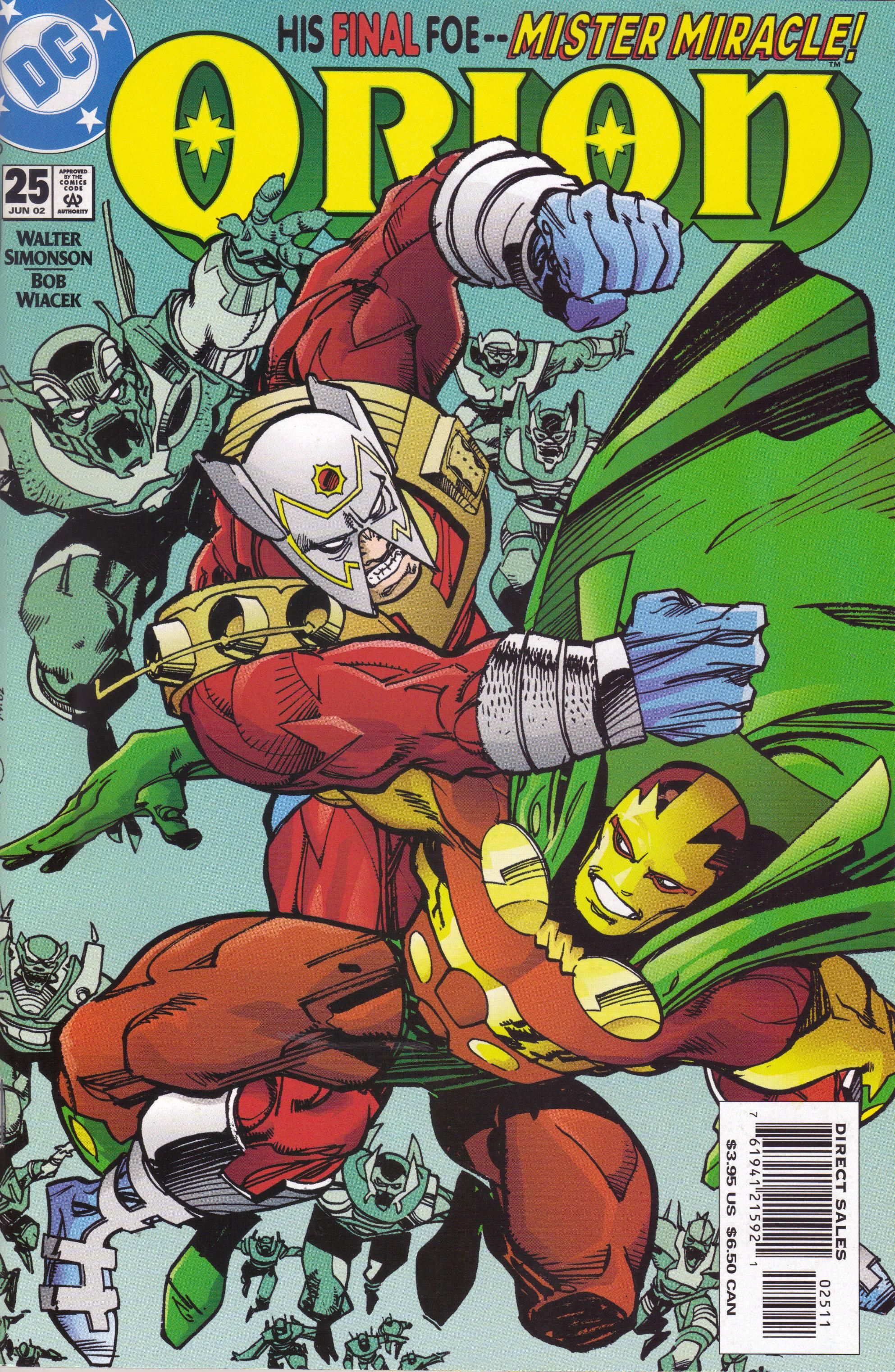

Orion by Walter Simonson (writer; artist, issues 1-12, 15-25), John Byrne (penciller, issues #13-14), Bob Wiacek (inker, issues #8-9, 19-25), Terry Austin (inker, issues #13-14), Sherilyn van Valkenburgh (colorist, issues #1-8), Tatjana Wood (colorist, issues #9-25), and John Workman (letterer); credits on back-up stories (where different from the main story): Frank Miller (artist, issue #3); Dave Gibbons (artist, issue #4); Eric Stephenson (writer, issue #6), Erik Larsen (penciller, issue #6), Al Gordon (inker, issue #6), Wood (colorist, issue #6); Howard Chaykin (artist, issue #7), Ken Bruzenak (letterer, issue #7); Jeph Loeb (writer, issue #8), Rob Liefeld (penciller, issue #8), Norm Rapmund (inker, issue #8), Richard Starkings (letterer, issue #8); Art Adams (artist, issue #10); Jim Lee (penciller, issue #11), Scott Williams (inker, issue #11); Simonson (writer/artist, issues #13-14), Wiacek (inker, issues #13-14); Kevin McCarthy (writer, issue #15), John Paul Leon (artist, issue #15); Allen Milgrom (penciller, issue #18), Klaus Janson (inker, issue #18); Eddie Campbell (artist, issue #19).

Published by DC, 25 issues (#1-25), cover dated June 2000 - June 2002.

I guess there are some SPOILERS below, although if you've ever studied classical literature, you know pretty much what's coming, don't you?

If anyone was going to pick up on Jack Kirby's work on the Fourth World, it would have to be Walt Simonson, wouldn't it? Simonson's epic work on Thor in the 1980s was career-defining and still considered the high point of the character, and the New Gods are, in some ways, DC's answer to the Norse mythology that was "Marvelized" in Thor, so why wouldn't Simonson do a wonderful job with Kirby's legacy?

This series seemed like a slam-dunk. Of course, it wasn't quite - 25 issues is a solid run, but as we read it, we can see that Simonson was rushing it just a little at the end before the cancellation hammer came down - but we did get two years of cosmic epicness that deserves to be read and loved.

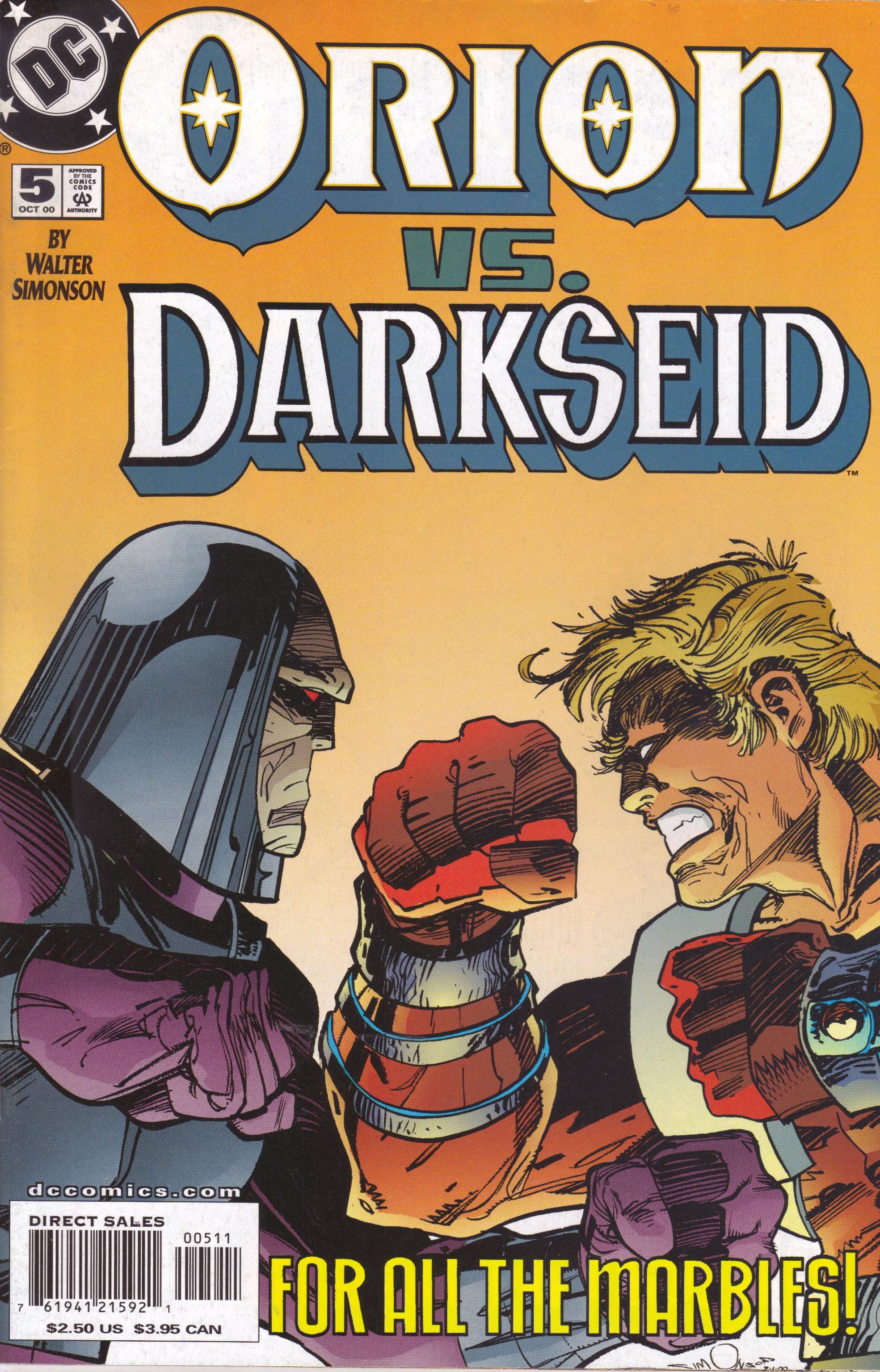

This post isn't about Jack Kirby, however. As a horrible comic book fan, I haven't read as many Kirby comics as I should, and I've never read his Fourth World stuff. Simonson's Orion may owe a huge debt to Kirby, but it's a magnificent comic in its own right. Simonson takes grand themes, draws the hell out of them, and unleashes them on the world. All we as readers can do is hang on! The themes are the stuff of classic literature: In issues #1-5, Simonson gives us an Oedipal complex writ large, with Orion defeating and killing his father, Darkseid, and taking over the leadership of Apokolips (the mother issues are largely absent, mainly because that's too creepy for mainstream comics, but Tigra, Orion's mother, is smokin' hot, because she's a New God, of course). After this, in issues #6-15, we get the corruption of the protagonist as he uses his power to "fix" the universe, leading to his inevitable downfall. In issues #16-24, Simonson shows us the exile of the hero and his quest for redemption, which leads to issue #25, the finale, where Orion is restored to full majesty. It's not that the plots are old, it's that they're some of the oldest in literature, and therefore are perfect for a book about ancient beings, and Simonson is smart enough to take those classic themes and inject them with some modernity so that the comic becomes less a dusty relic and more an update of those classics.

It's because Simonson is able to take themes that are embedded in humanity's desire to learn about the world, discover a moral compass, and grow beyond their forebears and make them seem fresh that makes Orion such a breathtaking read. Well, that and Simonson's artwork, which I'll certainly get to.

The book revolves around the "anti-life equation," the formula for controlling all sentient thought that Darkseid is always looking for. Fragments of the equation exist in the minds of humans, which is why Darkseid is so keen on dominating Earth. In the first story arc, he manages to access part of the equation to take over the minds of the inhabitants of a town in Nebraska, turning them into zombies who cut off the town from the outside world. Orion, meanwhile, has been told that he is not the true son of Darkseid, and this pisses him off. We join his torment in media res, as Tigra has told him Darkseid isn't his father before the issue begins and charges him with killing Darkseid before she dies. So Orion ends up in Nebraska, because Darkseid is there. Tigra dies, Orion saves the day in Nebraska (to a degree), and in issue #5, he and Darkseid fight to the death. Orion triumphs, and declares himself ruler of Apokolips. Unfortunately, his troubles are just beginning.

Simonson does a good job seeding the first few issues with long-running subplots, in the grand tradition of serial storytelling before everything was written for the trade and new writers took over titles every ten issues or so.

He brings back the Newsboy Legion, changes their name to the Newsgroup Legion (because they add a girl), and has them follow Orion to Apokolips, where they record the big fight between our hero and Darkseid. When they're scooped to the story by Jimmy Olsen (why Earth newspapers would care isn't explored, but they do), they decide to sell the rights to the fight for pay-per-view. They need money because a man named Arnicus Wolfram (talk about a COMICS! kind of name) is busy foreclosing on tax-delinquent properties in Suicide Slum (Metropolis has a slum?) in order to gentrify them and build a shopping mall. The Legion wants to save Suicide Slum but they have no money. Wolfram himself will be a major enemy to Orion much later on in the series. Meanwhile, Darkseid's clever gambit of fighting without weapons means that Orion must divest himself of his mother box, the sentient computer that guides and advises him. By shedding the mother box, Orion sets the stage for his twisted rise to power and subsequent fall. It seems like an innocuous thing - of course Darkseid would want to fight Orion mano-a-mano - but Simonson cleverly takes it in a fascinating direction.

Orion, being a hero, wants to cleanse Apokolips of Darkseid's terrible influence, and he begins setting things right. In issue #11, he is "given" the anti-life equation by ... well, it's complicated. Let's just say the power to control all sentient thought is now his, and he intends to use it! Through various machinations, Orion "converts" Apokolips to his cause, then moves on to Earth, where he enlists the Justice League to help him.

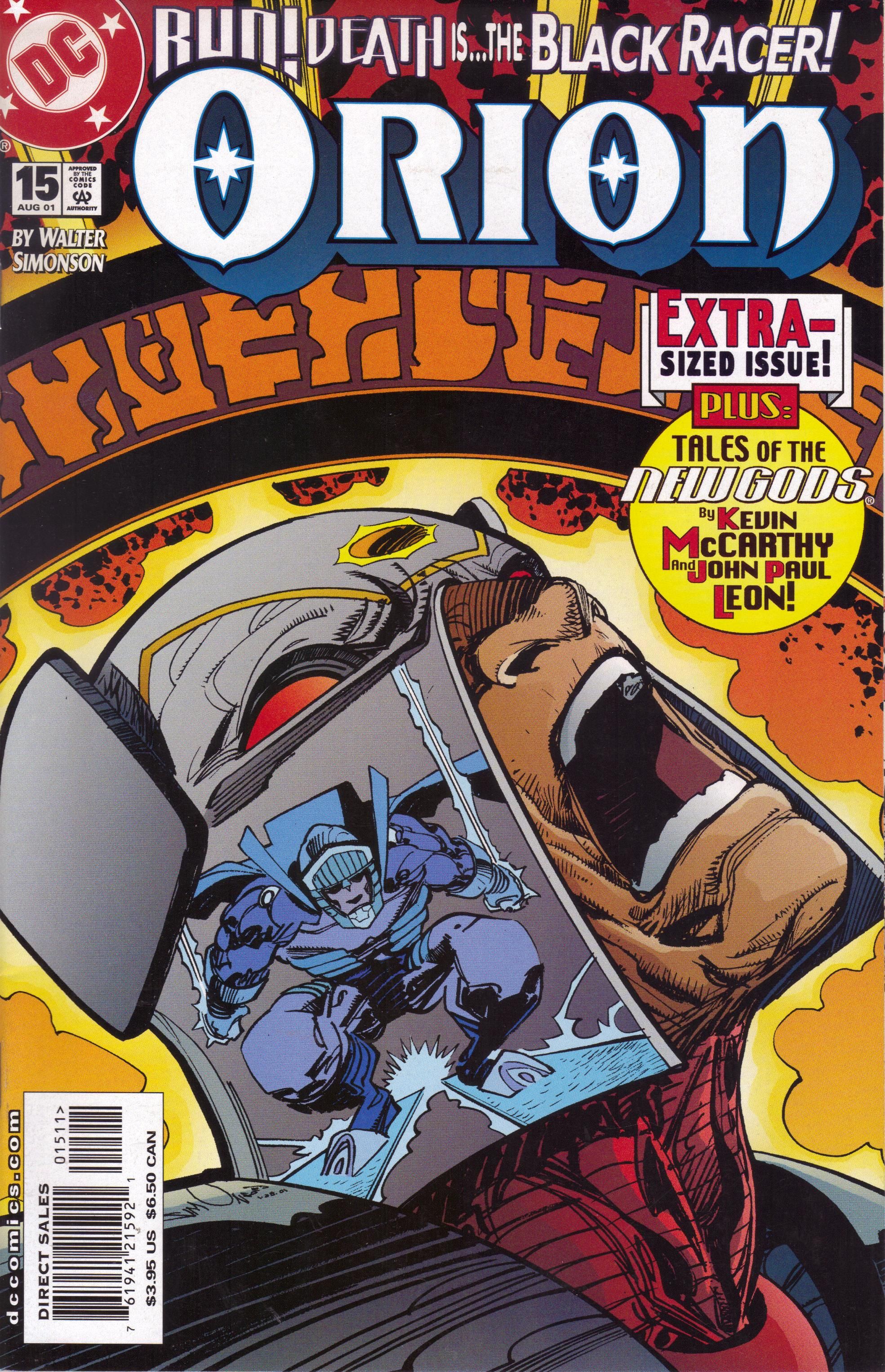

This is where Darkseid returns to the book - he is not dead (unsurprisingly) and he's plotting with Metron to rein in the rebellious hero. In issue #15, Darkseid affirms that Orion is his son, his and Metron's plot is foiled, but at the last moment, a mysterious New God shows up and saves the day by teleporting Orion to a different plane of existence. Orion's hubris has led to his utter defeat.

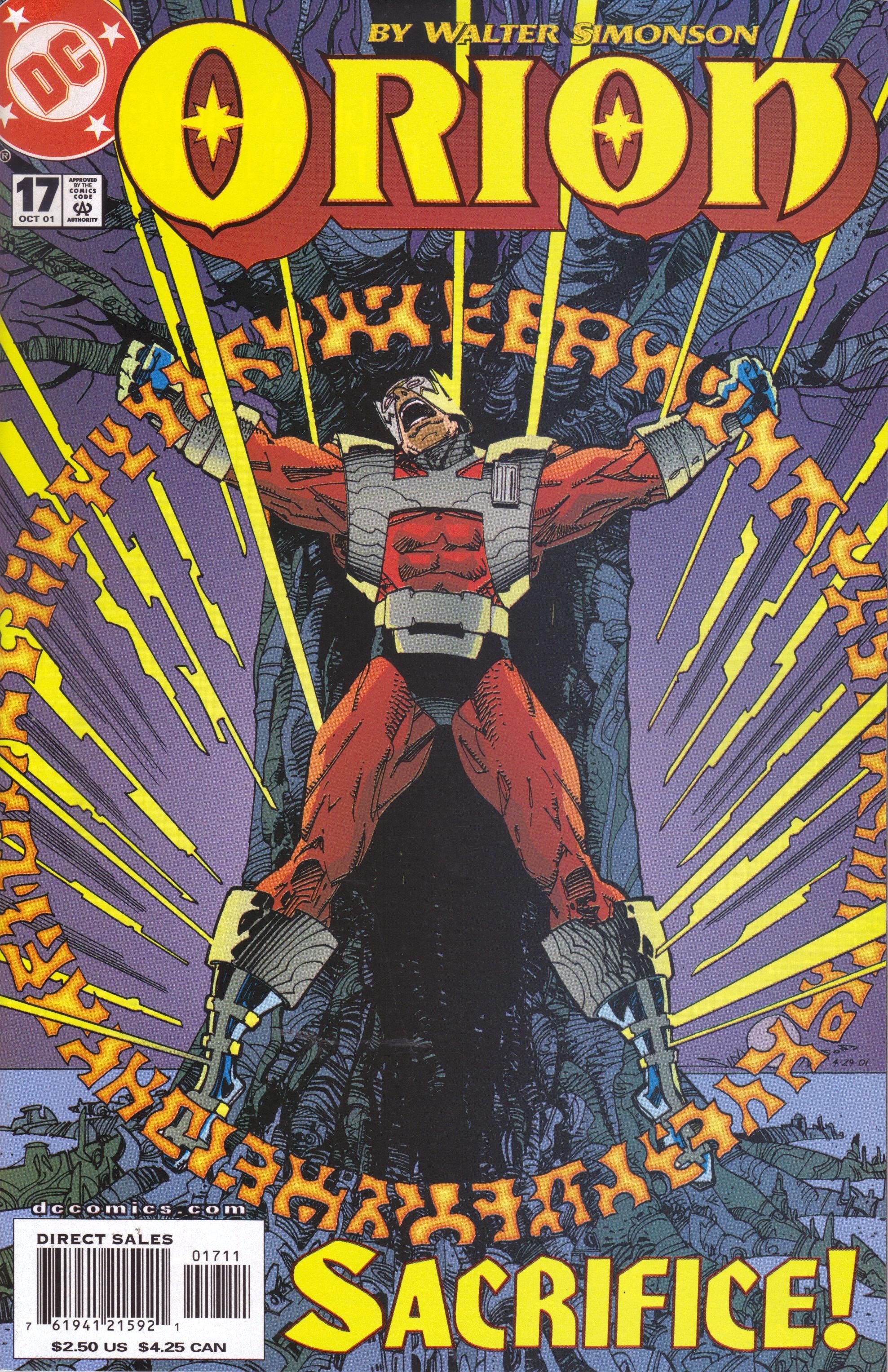

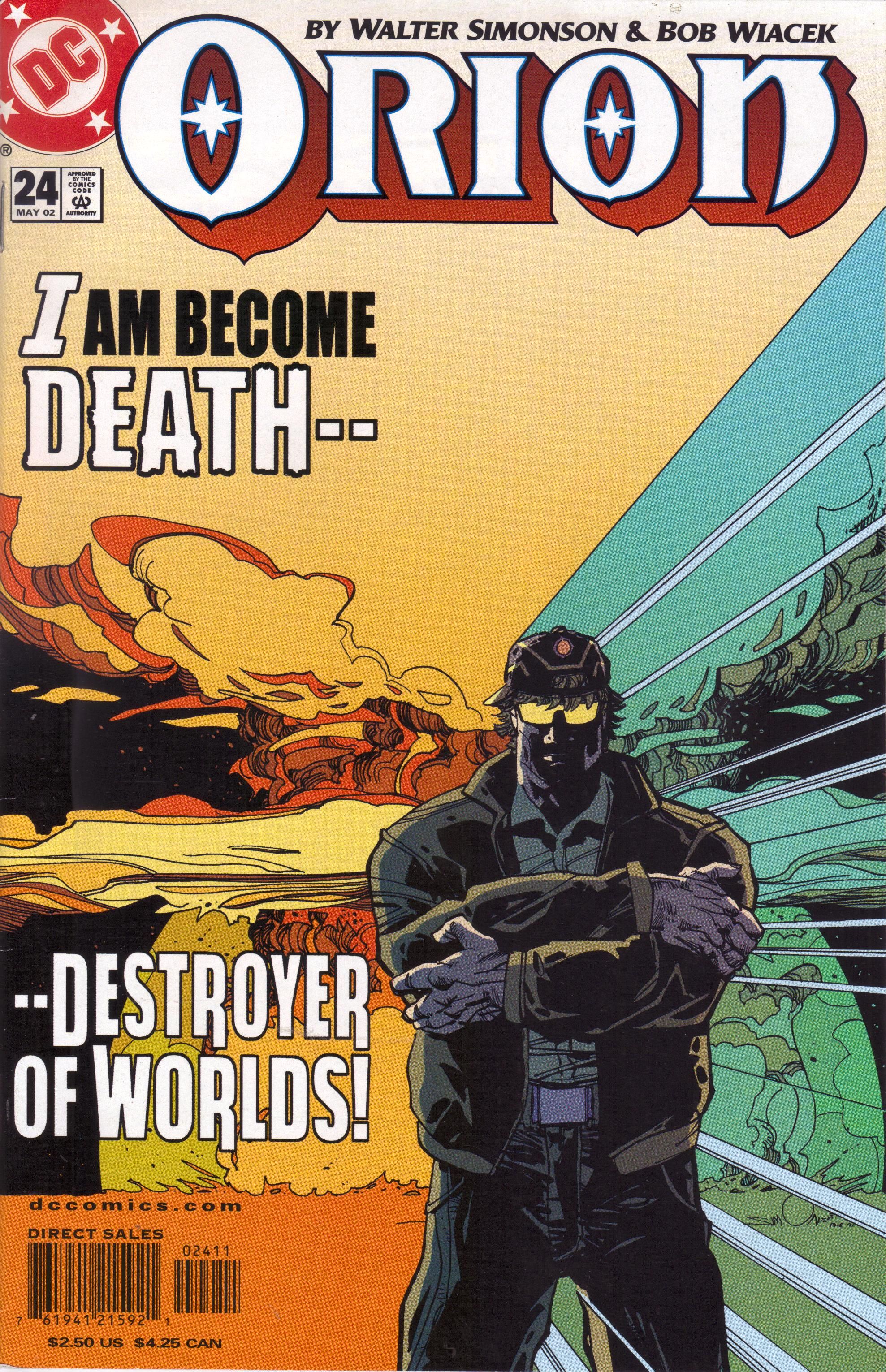

Of course, this is a serial, so Simonson gets to destroy Orion's life and then put it back together, as the next section of the book deals with Orion's return, another typical heroic theme. He is tempted by something that looks like Tigra to lay down his burden (in other words, his life); he meets Cain, the original murderer (who now calls himself Clockwerx); and he battles a demon that wants to eradicate all existence and manages to purge himself of the anti-life equation in the bargain. Unfortunately, he ends up in a coma and eventually winds up on Earth, where Arnicus Wolfram re-enters the series, as he's looking to place his consciousness into Orion's body and thereby ensure his immortality (he's already lived for centuries by using mortal bodies, but that gets tedious and they do, after all, age). Orion defeats him, of course, in issue #24, which features some nice exposition by Simonson about why mortals probably shouldn't mess with gods. The finale of the series features Scott Free, who explains quite a bit to Orion about the anti-life equation and why he's been so out of sorts in the series, and it leads to Orion reclaiming all his power, twisting time a bit to help Scott (for reasons I won't get into here), and making sure Darkseid knows that he's back and still fighting. Yet again, Simonson has taken his hero on a quest, this one leading to restoration and rejuvenation. If the ending of the series seems a bit too much like Simonson simply resetting the status quo, at least he did it in both an entertaining fashion and one that follows in the footsteps of classical writers, setting Orion firmly in the grand tradition of myth.

As Orion is largely plot-driven, I've been trying to avoid the specifics of what happens. I can't really discuss the book without writing about Darkseid's "death" and return, but I don't want to give away how Orion gets rid of the anti-life equation, for instance, because it's fairly clever, or what Scott's role in the series is, because it's fairly important.

And while superhero stories often follow mythic themes, what makes Orion more impressive than usual is the way Simonson keeps it fairly pure - unlike many other superhero comics, Orion does not have extraneous stuff shoehorned in, especially in the way of character development. Simonson does bring in some human characters, which allows him to ground the stories slightly, especially when Orion is battling Arnicus Wolfram and he seeks help from Melissa, a streetwise teenager, but generally, these are archetypes battling, and they have no need for character development. Orion does learn how to be slightly more compassionate, but as he was a hero at the beginning of the book (a bit rough, true, but still a hero), it's not like he needed to learn a lot of compassion. It's a testament to Simonson's storytelling that he doesn't delve too much into the psyches of his main characters, choosing instead to allow them to reveal their character through their actions. Orion doesn't need to talk to others about how much he cares - we see it in his actions. Occasionally he allows himself some introspection, but it's usually brief and ended the moment the action begins. Simonson, as a writer/artist, knows that showing is far more effective than telling, and he almost always chooses the former.

This leads into another reason, perhaps the primary one, why Orion is a Comic You Should Own - Simonson's art. Without Simonson's art, the book would be an entertaining read, no doubt, but not as epic as it is. We need only look at Byrne's fill-in art on issues #13 and 14 - Simonson makes sure that Byrne gets to draw a lot of cool stuff, including Gedirath, who has been trapped on an asteroid in deep space for eons, but Byrne's cleaner lines, while nice to look at, lack the insanity of Simonson's artistry. (I should point out that Simonson, with all that detail and action and fantastic sound effects, drew the first 12 issues and the final 11 issues of this series, and on the two he didn't draw the main story, he drew the back-ups, and as far as I know, the book was never late.

That's because Simonson isn't a prima donna. Okay, rant over.) Simonson is one of the few artists in comics who could do justice to Kirby's cosmic work, and he does so very well in this series. If you have read a comic ever, you know what Simonson's work looks like - he has a fierce energy to his pencils that helps drive everything so that Simonson comics almost read in fast-motion even though they're packed with details. Given the milieu in which this book occurs, Simonson gets to draw a lot of crazy things - the Source Wall, where New Gods die; suicide jockeys, bizarre Apokoliptian creatures tasked with killing Tigra; the horror of Billion Dollar Bates, the human with the entire anti-life equation locked inside his head whom Desaad has turned into a grotesque and giant clone (in later issues, he draws hundreds of them); a hellborer, a mighty weapon of Apokolips; an immortal demon in the shape of a giant dog; the anti-life equation being dumped into Orion's head (which is a marvelous few pages, climaxing with the scene below); the eerie dimension where Clockwerx abides; the demon Ecruos, which wants to nullify all existence; Slig of the Deep Six commanding giant monsters of the ocean; plus oodles of explosions, plenty of Kirby Krackle, and more brightly- and oddly-dressed New Gods than you can shake a stick at. I mean, it is comics, after all.

One thing Simonson does very well is draw "unrealistically" in order to convey a realistic feeling. While that might not make any sense, maybe an explanation will help. Like many other masters of the form, Simonson deliberately draws some figures distorted because of where they're placed in the panel. Many artists understand depth in a panel, but over the years, as photo-referencing has been used - not as a helpful tool, but for other, less noble reasons - some artists have forgotten that occasionally it's fine if the figures aren't anatomically perfect because the distortion helps create a sense of motion and perspective. Many artists instinctively know this, of course, because they draw characters punching toward the reader and the fist is larger than any part of the body.

Simonson, however, takes this even further - the characters' bodies are distorted, but so too are their faces, expressing the extreme emotions coursing through them. Simonson is never one for subtlety, and when he's dealing with gods, he chucks even that - these characters wear every emotion on their sleeves, and Simonson's grand scale feels right for it.

Of course, Simonson knows how to go completely bonkers with the cosmic stuff and still manage to keep the book focused on the individuals, mainly Orion. Even when his star is completely overwhelmed by the size of his antagonists (and several of them are gargantuan), Simonson makes sure to keep Orion as his fulcrum. A superb example of this is when the Ecruos rises from the depths, intent on destroying the world tree that Clockwerx guards. The Ecruos is seemingly miles high, and Simonson's drawing of it fills the entire page, with Orion but a speck against it. Simonson, however, gives his star a halo of superpower and even makes sure that the body of the Ecruos angles our eyes downward to the focus point of Orion. It's an impressive achievement, and when Orion turns the tables on the Ecruos, he grows in size until he dominates the remnants of the demon. Simonson accomplishes this easily and in a few pages, and it's interesting that such a quick reversal of fortune doesn't diminish the initial appearance of the Ecruos at all. It's also interesting that when Orion defeats Arnicus Wolfram, Simonson doesn't allow the actual detonation of a hydrogen bomb to be as majestic as the other, comic-booky explosions that litter the book. Wolfram's fate is pathetic, and the hydrogen bomb is no cause for celebration, so Simonson downplays it a little bit.

The book is a visual feast, not only for Simonson's art, but for the back-up stories. This is a tremendous idea - this is when comics cost $2.50 for 22 pages, and DC only charged extra for the giant-sized issues. Simonson wrote in issue #2 that he wanted back-up stories to take some of the pressure off himself to do 22 pages every month (considering he drew 30 pages of issue #15, 38 pages of issue #25, he never actually missed an issue - the back-up stories in issues #13 and 14 were only 5 and 4 pages, respectively, but still - and not every issue had a back-up story, his protestations sound silly) but also because Kirby planned the Fourth World as a group of interconnecting stories, and he wanted to do that. It may have allowed Simonson to draw fewer pages (issue #3, which featured the first back-up story, was 16 pages of Simonson art, as an example), but he also fills each page with so much detail that 16 pages of Simonson feels like more than someone else's 22 pages.

And, of course, it's great to see the talented artists working on the back-up stories - Chaykin before he became lousy, Liefeld when he has a quality inker, Adams doing any interior work, Campbell drawing Darkseid - and they do add a nice deeper level to the world that Simonson is creating, because they focus on characters who show up only briefly in the main story. Presumably the back-up stories ceased because Simonson was under some pressure to wrap everything up, but it would have been interesting to see more of them as the book progressed.

Given DC's woeful policy of collecting their back stock, it's perhaps not surprising that there is one trade of Simonson's Orion, collecting merely the first five issues (plus a few other Simonson-penned Fourth World stories that I don't own but probably should). With Marvel releasing Simonson's Thor in a giant omnibus of over 1000 pages, I can't believe it would kill DC to release the 25 issues of Orion as an Absolute Edition, especially as Simonson's artwork would look dazzling in a larger format. Don't hold your breath on that, however. The single issues of Orion are fairly cheap - most of mine were cover price when I went searching for this series a few years ago. Orion deserves a higher profile in the comic book world than it currently has. It's a tremendous work of myth and epic, as it grabs you in the first issue and never lets you go. Find it and read it! You will love it.

Speaking of Comics You Should Own, you can always peruse the archives for more. They're just waiting to be read!