This is one of the best Two-Face stories ... and it's less concerned with the number two than you might expect!

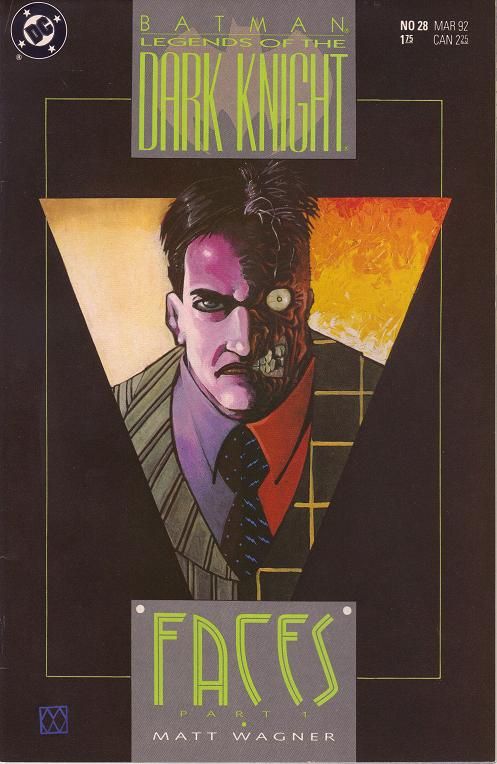

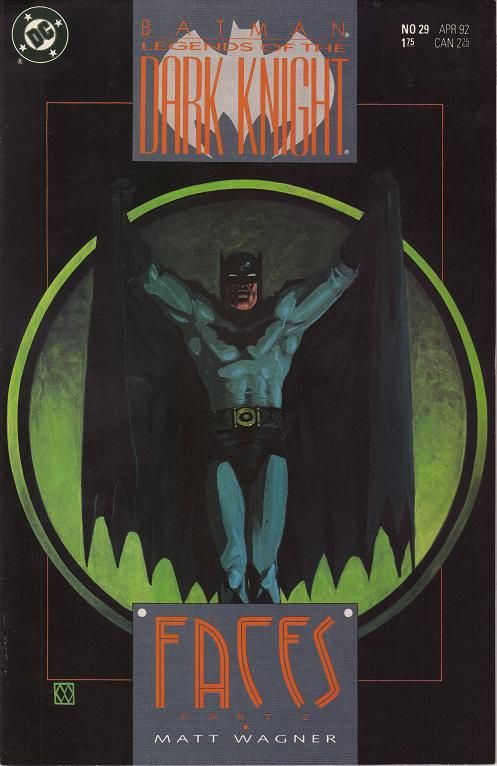

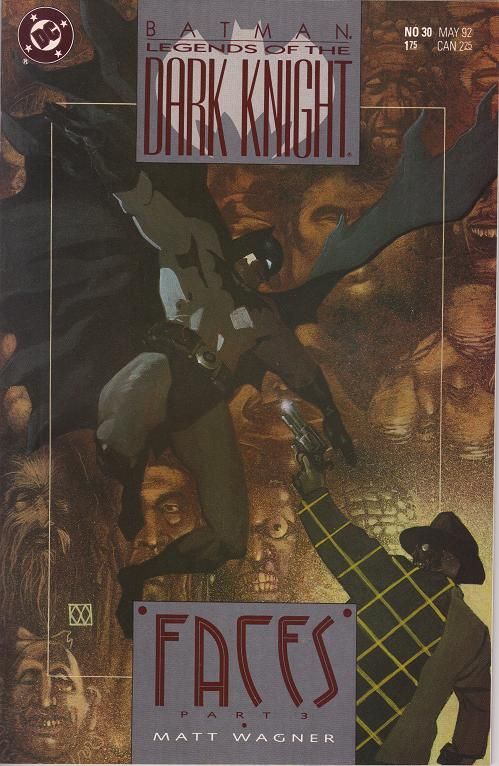

Legends of the Dark Knight by Matt Wagner (writer/artist), Willie Schubert (letterer), and Steve Oliff (colorist).

DC, 3 issues (#28-30), cover dated March - May 1992.

Minor SPOILERS ahead, because I kind of have to. I apologize for it, but as you know, these comics are so good, it doesn't matter if you know what's coming!

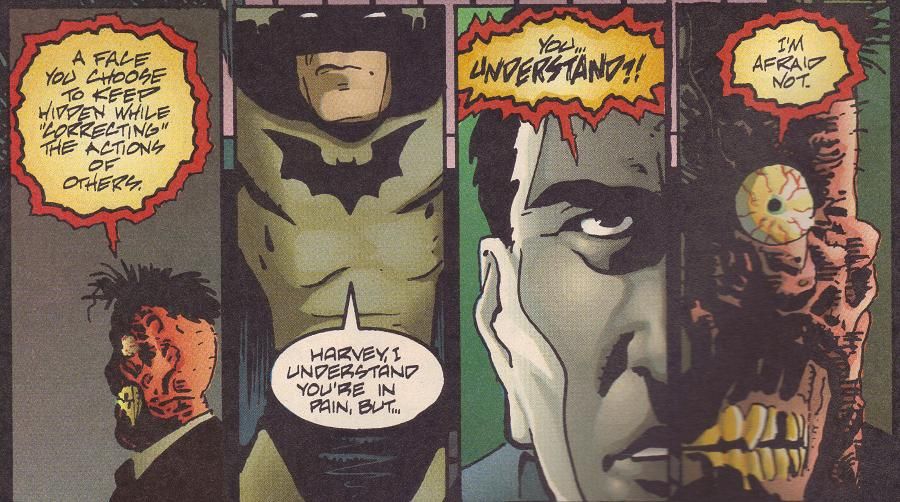

Matt Wagner does far too little interior art these days, and it's a shame, because he's a marvelous artist. He's also a very good writer, and so this comic is a treat. Many of the Legends of the Dark Knight stories don't rise to the level of Comics You Should Own - even the God of All Comics' arc, "Gothic," falls a bit short - but "Faces" is a wonderful story. Wagner, unlike many writers, doesn't delve too much into Harvey Dent's duality and his internal struggle, but he does, like many writers, show how similar Harvey and Bruce Wayne are. There's nothing wrong with that - it's all in the execution, after all. And Wagner does it far more subtly than most.

One place that Wagner always shines is in his design work. His blocky style is remarkably graceful, and in most of his Batman work, he thickens the inks to make the world of Gotham even darker. Some of this comic's dark look can be attributed to Oliff, of course, but the first page of the arc sets the stage for what we're going to see: An exterior shot of Arkham Asylum with nothing but blacks and whites and browns. The ornate iron fence and the worked "Arkham" over the gate blend into the black house behind it and the black silhouette of the leafless branches of a tree, all of which seems to form one, demented building. The one window looks like a shadow cast into the house, while the half-moon in the sky casts a stark white onto the chimney and the gables.

It's a haunting image, one that reflects the duality of the arc (which isn't surprising, as it's about Two-Face).

As the story is called "Faces" and is concerned with masks people wear, it's not surprising that the plot kicks into gear at a costume party - a masque. Wagner adds a creepy sheen to the full-page drawing of the party's establishing shot, and not just because of the devil who looms up from the bottom right or the figure of Death off to the side. Wagner's characters always have a look of desperation about them, and the rabbit and Statue of Liberty in the middle of the page, despite laughing and enjoying the party, also seem to be trying too hard. A fat Superman and a glazed-eyed unicorn complete the tableau, while Bruce Wayne, a pensive Napoleon, lurks in the middle ground. It's a strange scene that Wagner contrasts later with the double-page spread of the circus "freaks" that Two-Face has assembled. Wagner nicely sets up the difference between these privileged people wearing fake masks and the people who don't need to wear masks to look different. He does it without being too obvious about it, too.

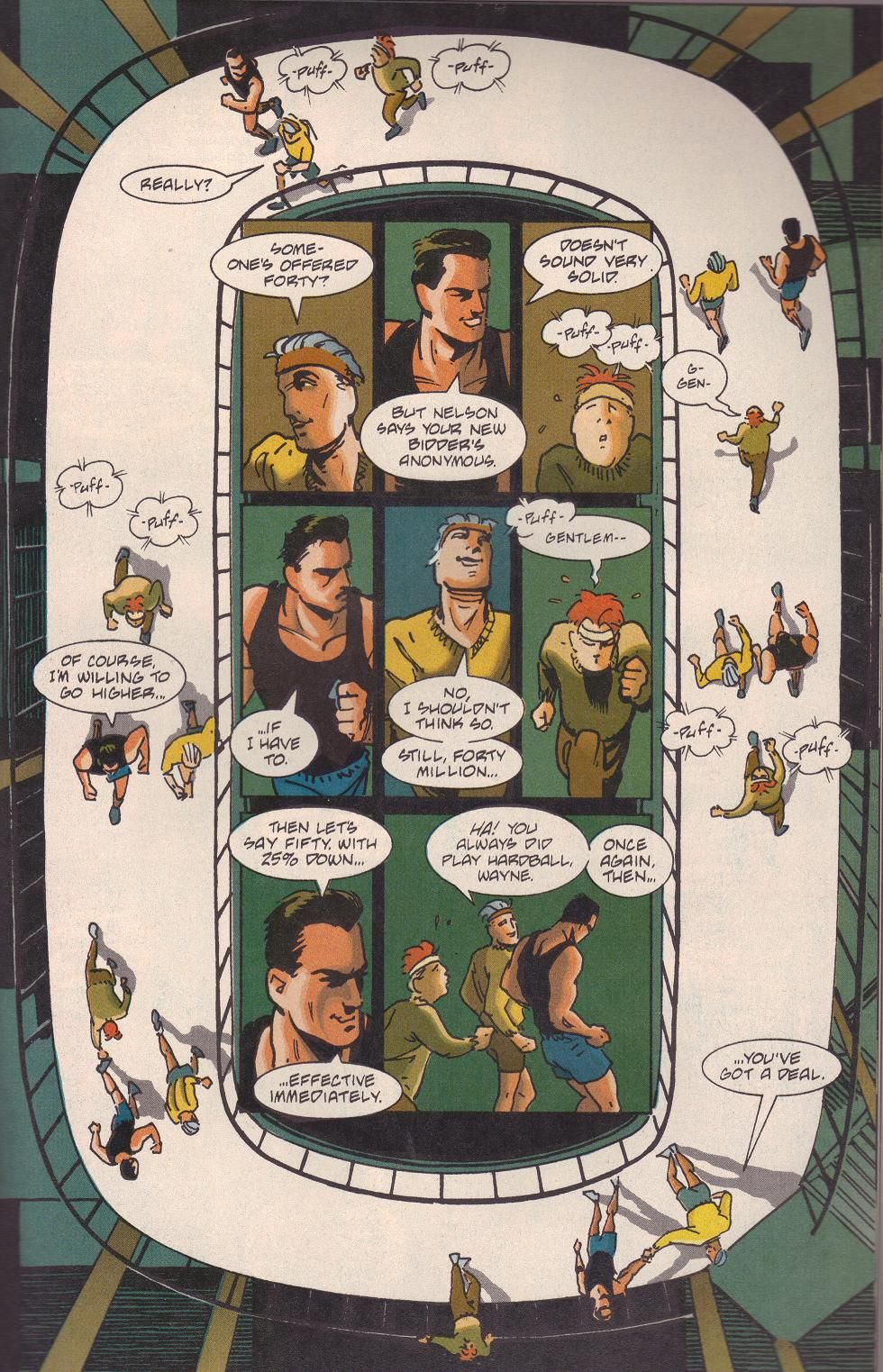

Wagner lays out the pages beautifully, too. When Bruce and Paul D'Urberville settle their business in issue #28, Wagner shows them jogging around a track. The oval fills the entire page, and in the middle of it, Wagner does a nine-panel grid (eight panels, actually, but the final one is twice the size of the others - the grid is still a nine-panel one) that shows the two men talking to each other.

He incorporates both the grid in the middle with the oval, switching from the characters talking on the track to the characters talking in the grid. It's a wonderful technique - something that can only be done in comics, and something more artists should do. In issue #29, he shows Nelson Wren, wracked with guilt over his complicity in Harvey's plot (despite not knowing he's working for Two-Face), wandering around his office, his path through the room dotted on the floor like he was in "The Family Circus." He uses that technique in issue #30 when Wren is trying to get away from Harvey but all he finds are freaks. Wagner also varies his panel size very well - when Batman checks the house of a potential victim in Harvey's scheme, Wagner fits his preparations into smaller panels to speed up the process and to show how thorough he is. This is more common among artists, but Wagner does it very well. Whenever Wagner wants to show how efficient Batman is (the checking of the house, the way he escapes Harvey's blimp in issue #30), he changes the size of the panels to give us the very minimum amount of information. We get everything we need, but it also feels like Batman is simply doing things faster than a normal person, because he knows exactly what he has to do. What's most impressive about the art and writing is how dense this book is, but how easily readable it is. Wagner never skimps on information, and he likes labyrinthine plots, so there's a lot of verbiage in these issues. But the way Wagner breaks down each page is marvelous, as he makes sure none of the words get in the way of the art and he also pulls back and lets the art tell the story when he needs to. And he doesn't shrink away from bigger spreads, either, so there's still some examples of nice set pieces (the final pages of both issues #28 and 29, for instance).

Wagner always gives us interesting characters and settings, too, and that's in abundance here. I love his Batman - he's slim and not overly muscular, much more Golden Age-ish than most artists draw him.

Wagner's famous creation, Grendel, shares this characteristic - we can believe that Hunter Rose and Batman can engage in the aerial gymnastics that they do because they don't have ridiculous musculature, but we also believe they could be excellent fighters. Bruce Wayne is debonair and suave, too, and he's effortless about it - in Wagner's world, he's a true blueblood. Some artists make Bruce too uncomfortable in his own skin, which makes its point that he'd rather be smashing punks' faces, but Wagner understands that before his parents were killed, Bruce was raised as an aristocrat, and after their deaths, he didn't change. As an adult, it's necessary to remain so to throw off suspicion. It has become second nature, which means that even if it's an act, it's still part of him. This gets back to the theme of the story, which we'll get to soon. Paul D'Urberville, with his Gothic-Romantic tinged name, appears to be dying of consumption throughout the story. Nelson Wren, the real estate agent who acts as the catalyst for much of the plot, is indeed wren-like - small, meek, and easily overlooked. He's easy prey for Manon, the French girl who seduces him and gets him to betray both D'Urberville and Bruce Wayne. We feel much more pity for Nelson because of the way Wagner draws him, because we understand why he would fall for Manon and into an ethical dilemma. Wagner's depiction of Harvey's circus freaks is well done, too. He begins by simply making them speechless monsters in Harvey's festival of horror, but as the arc moves on and we begin to see where Wagner is going with the story, he begins to humanize them, until at the end when they're just people - people who look different than most people, of course, but still regular folk.

He does this through their speech, of course, but it's nice how he manages it by subtly altering their body language and facial expressions.

The reason this is a great Two-Face story is because Wagner doesn't get into Harvey's duality in the traditional manner, with Batman trying to convince Harvey that he can overcome his evil side (he brings it up briefly, but it's not the focus). This is a much more interesting take on the way Harvey sees the world and the way people hide who they are. Many writers have focused on Bruce's obsession with masks (in the modern age, it's a particular pet theme of Doug Moench, but Denny O'Neil's initial arc on Legends of the Dark Knight delved into it quite a bit, too), but again, Wagner does it better than most. Even at the costume party, he doesn't wear a mask, simply dressing as Napoleon with an exposed face, but he's still playing a part. But Wagner gives much more "screen time" to Bruce Wayne than many writers, and that's always interesting to see. We get a good look at how the dual identities often dovetail in unusual ways - Bruce wants to buy a South American island from D'Urberville, the same one that Harvey wants to create a "utopia of freaks," a place where he and his circus brethren can live without the stares of the "normal." Bruce's involvement in the transaction is a MacGuffin - we never learn why he wants the island (he says "Privacy. Leisure," one of which he already has and the other of which he never partakes of) - but it allows us to see a bit of how he operates as a businessman and bon vivant. Bruce Wayne's interest in the island means Harvey must come into the open, setting the plot in motion. But the plot, as intricately as Wagner plays it out (and he always does this; it's one of the reasons why he's such a good writer), is simply a way for Wagner to delve into the idea of beauty and how that affects people. Nelson Wren is a success, but he's unattractive. When Manon shows interest in him, he loses all his inhibitions and falls into crime, mainly because he can't believe a woman as attractive as she would show an interest in him. Of course, she's not all she seems, because everyone in this comic is wearing a mask.

D'Urberville is hiding something that, according to Harvey, makes him a hypocrite. Harvey's entire scheme is predicated on the fact that society ostracizes the freaks of the circus because they can't stand to face the imperfections in themselves (which leads back to D'Urberville's hypocrisy). But Wagner doesn't let Harvey off the hook - his problem is not that society ostracizes him, but that he cuts himself off from society. He encounters a circus performer with a "two-face" much like his, and he screams at him, "You're a freak!! A freak!!" and the performer responds, "But I am not a monster." Harvey's ultimate mask, if you will, is that he tries to hide his monstrosity from people by deflecting the blame onto society at large. Wagner does an excellent job showing us that Harvey is, at last, deluding himself. Nelson Wren and Paul D'Urberville might be hypocrites, but Harvey's as bad as they are. Too often writers focus on the tortured duality of Harvey's psyche, which isn't a bad tactic. Wagner shows that it's not quite as dual as Harvey would like - when he's confronted by something that doesn't fit into his world view, he's perfectly willing to allow the monster to win. Writers have gone back and shown the pre-Two Face Harvey as being a bit less sane than maybe is healthy, but Wagner doesn't need that - he's adept at showing it in the middle of an interesting plot.

The arc relies on a bit of knowledge on the readers' part - Wagner doesn't explain how Two-Face got this way, nor does he get into the idea that Harvey himself was an attractive person before his accident, which helps appreciate his machinations a bit more.

But that's a relatively minor criticism, because Wagner is able, very quickly, to get across the themes he's working with and an astute reader can pick up on Harvey's insecurities as the arc moves along. It's always nice to read a superhero story that assumes the reader can keep up. Wagner doesn't stop for us, and it makes the arc move swiftly but still feel hefty.

"Faces" has been collected in trade, and it's well worth your while. It's an essential Harvey Dent story, not because it fills in any blanks of his life, but because Wagner digs deeper into Two-Face's twisted mind than most writers do. And it has that brilliant art, too! And be sure to check out the archives, because I'm gearing up to update them much more quickly than I have been!