Matt Wagner's masterpiece is our next installment. For now, I'm only looking at the first twelve issues. Next time, we'll go beyond that. And, as always, SPOILERS abound in these posts!

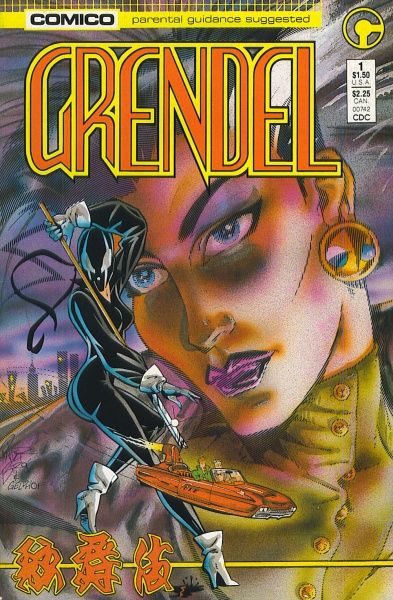

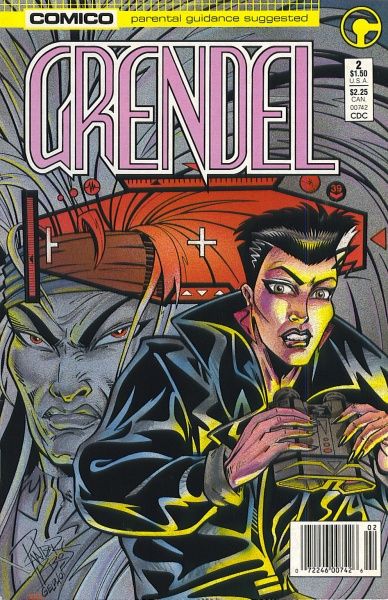

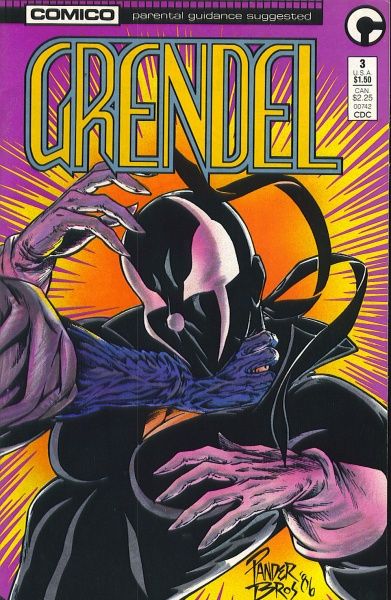

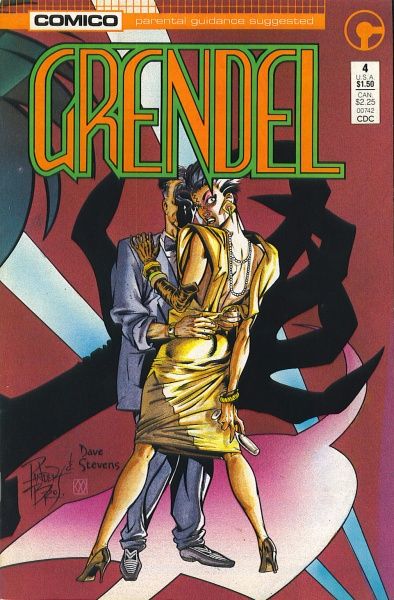

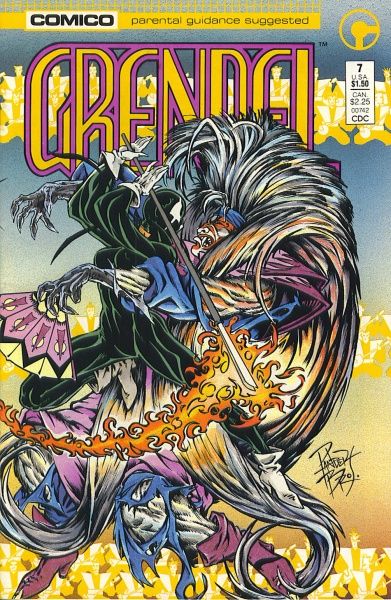

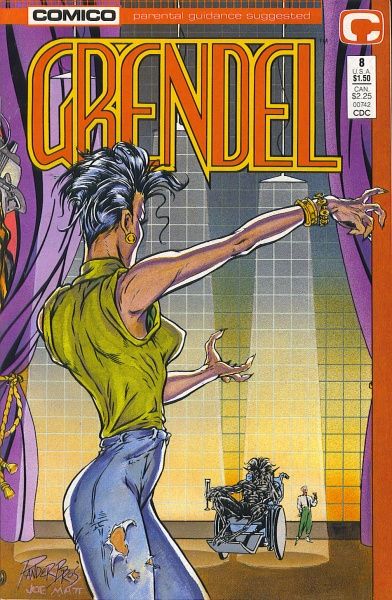

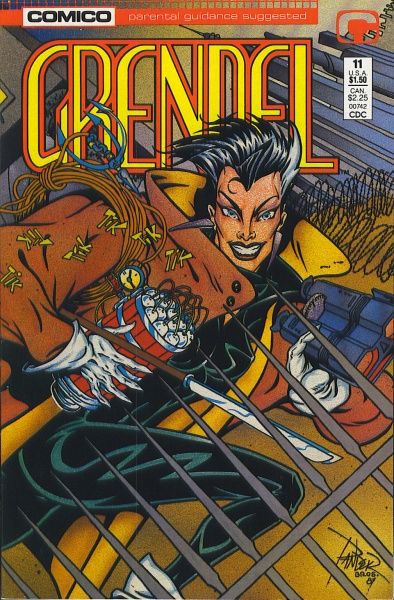

Grendel by Matt Wagner (writer), Arnold and Jacob Pander (pencillers; inkers, issues 7, 9, 12), Jay Geldhof (inker, issues 1-2, 4-6, 8, 10-11), andRich Rankin (inker, issue 3).

Comico, 12 issues (#1-12), cover dated October 1986-September 1987.

Matt Wagner's seminal creationwas actually not that good the first time he appeared. I encourage people to track down the earlyappearances of Hunter Rose, the original Grendel, some of which are handily collected in a nice hardcover from Dark Horse that recently came out. They certainly aren't great comics, because Wagner was definitely still finding his way, but they are interesting. In later years, Wagner has revisitedhis first Grendel with several mini-series, and soon he'll be doing the art on a new one, and Hunter has become more interesting as those series have come out. But when hefirst appeared, he was a bit of a stereotype. Then Comico started an ongoing series, and Wagner decided to leave Hunter Rose in the grave. But how wouldGrendel appear without Hunter Rose?

The idea Wagner came up with was sheer genius and spurred his creation to new heights. He decided that Hunter Rose himself was NOT Grendel, but that Grendel itself was a force that could "possess" people. Therefore, Grendel could be anyone. Immediately, Grendel went from a fairly normal fantasy character (the precocioussavant who becomes bored with life and turns to assassination and other crimes) with a nemesis (the ugly avenging force of good thatappears grotesque when compared to the playboy killer) toa complex psychological drama of how we conceive evil and what exactlymakes someone evil. The ongoing lasted 50 issues (sort of; we'll get to thatbelow), and the first 12form a glorioustale of revenge, horror, and injustice. It's a frighteninglook at what drives people to murder and why it canoccasionally be defended.

Wagnerintroduces us to Christine Spar, "Grendel's Granddaughter," who wrote a biography ofHunter Rose and gained fame as a result. Christineis the perfect character to investigate Hunter Rose; she is the daughter of Stacy Palumbo,Hunter Rose's adoptive daughter.Due to Stacy Palumbo's ratherupsetting past (her husband raped her and thenhanged himself on their wedding night, and spent the rest ofher life in an institution), Christine was also adopted and only found out who her mother was late in Stacy's life. Moreover, Christine is also a widow with a young son, Anson. Therefore, she is already shadowed by tragedy when the book begins, and soon it will grow darker in her life.

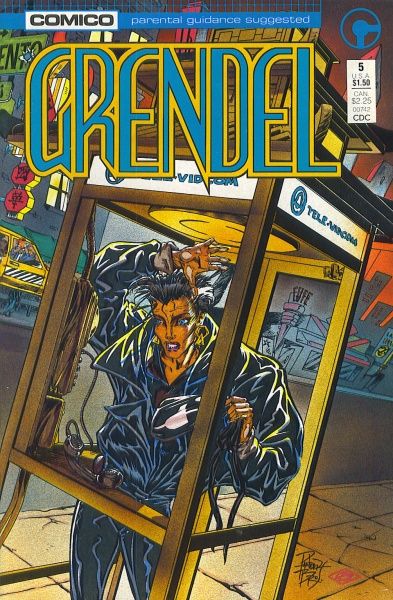

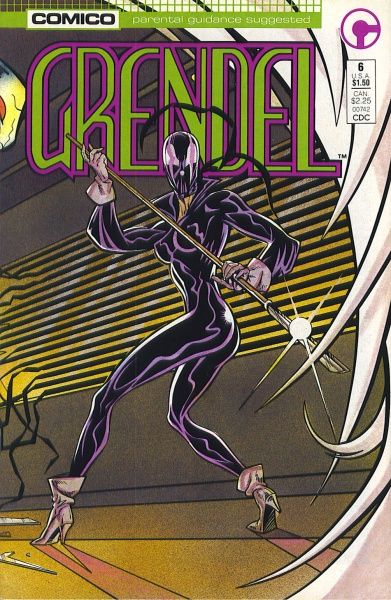

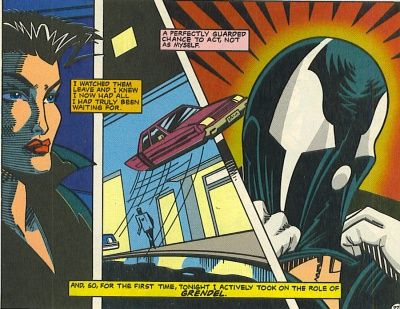

Christine's best friend, Regina, takes her to a Kabuki troupe performance in the first issue. This turns out to be a bad idea, as she goes backstage after the performance and meets the star, Tujiro XIV. Tujiro is a creepy performer, as he licks Christine's hand and plucks a hair from Anson's head. Christine is mesmerized by him, but she also is creeped out. Later, Tujiro kidnapsAnson. Christine tries to go through the police, but they're unhelpful. Christine does some investigating, and finds out that other boys disappeared right after seeing the Kabuki show. She has no proof, so she can't go to the police. She finally decides to break into the New York Public Library, where Hunter Rose's Grendel gear is on display. She steals the outfit and the double-pronged fork Hunter Rose used as a weaponand goes to San Francisco to hunt Tujiro. At the moment she puts the outfit on, Grendel's old enemy, Argent, realizes that "he's" back. The stage is set.

We'll get back to Argent, because he's important to the saga as a whole. Christine, meanwhile, arrives in San Francisco and meets Brian Li Sung, the stage manager. As her cover, she tells him she's trying to land an interview with Tujiro. Regina tracks her down, and Christine knows instinctively that the police are bugging the phones. This leads Argent, who works with the police, to give us a hint of what's happening to Christine: "She is obviously weaving her friend's thoughts," he says. "She does not merely act like Grendel ... She is." We don't quite understand how Christine is so good at "being Grendel," and Argent's idea makes sense. We get more of this as the series goes on, but for now, Wagner keeps it vague. Christine discovers where Tujiro is staying, and one night, while he's out, she breaks into his hotel room. There she discovers the first horrific thing about Tujiro: he collects eyes. In that instant, Christine realizes her son is dead, and for the second issue of a new series, it's a bold move by Wagner. We weren't hopeful about Anson's fate, but the confirmation that Tujiro did actually kill him is still unexpected, and we feel the kick in the gut that Christine feels. With that realization, this switches from a tale of rescue to one of pure revenge, and leads Christine into darker and darker territory.

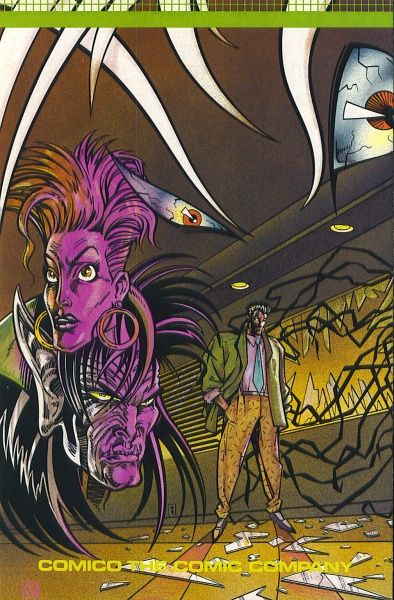

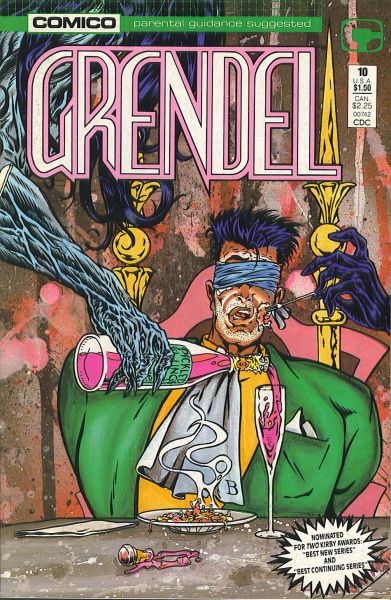

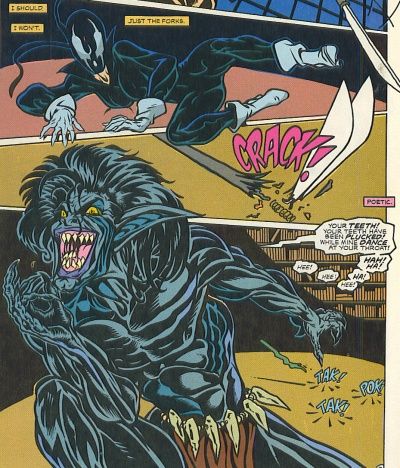

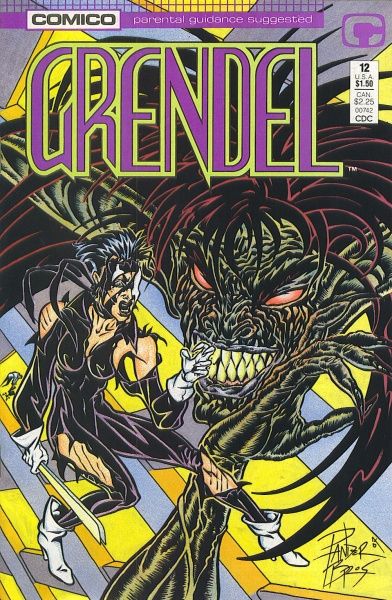

Tujiro finds her in his bedroom and fights her, defeating her rather easily and forcing her to flee. As she continues to stalk him and his associates, she discovers a more disturbing truth about him: he's a vampire. Wagner stated in the letters column that he wanted to bring in a non-European mythology of vampires, hence Tujiro. The weakness of the book is that Tujiro isn't all that different from European versions of vampires, except in some superficial ways andperhaps with the harvesting of eyes. Still, when we learn Tujiro's secret, it's a shocking revelation. Christine doesn't know how to handlehim, but she continues to stalk him. Tujiro is also running a slavery ring, and he next targets Brian, with whom Christine is falling in love. So it becomes doubly personal for her - she still wants vengeance, but she also wants to save a budding relationship. Brian doesn't believe any of it, but as Tujiro closes in on Christine, he's drawn further into the battle. In issues #6 & 7, Christine tells him everything and confronts Tujiro. We see how deep she has gotten into the Grendel persona. She rigs all his tour busses to explode, killing his entire troupe. Throughout all of this, she has become more and more calculating, even sleeping with Brian the first time to keep him away from his apartment so the slavers couldn't get him. Despite her growing feelings for Brian, her revenge against Tujiro comes first. Surprisingly, her fight with Tujiro is unsatisfying, but Christine can't continue it. That's because this comic isn't really about Christine'sexternal enemies, either Tujiro or Argent. It's about her inner demons, and Tujiro is really just a catalyst. Several people complained that their battle was poorly done because it was inconclusive, but they missed the point. Christine's truenemesis is Argent, and Tujiro is just a way for her interior enemy, Grendel, to get into her life. Which he has, with a vengeance.

We see this throughout the first part of the book. As I pointed out above, Argent, who is somehow linked to Grendel, suddenly realizes that "he" is back, because he thinks it's Hunter Rose, even though he learns soon that it's Christine. In issue #2, he says that she is Grendel, becausehe understands that Christine, as herself, could never twist Regina like she has and figure out that the cops are bugging her. Somehow Argent realizes that whatever made Hunter Rose Grendel has moved on to Christine. Christine herself hasn't figured this out yet. When she returns to New York in issue #8, she begins to comprehend what Grendel means to her. When the cops pick her up at the airport and take her back to Argent's house, she discovers that they are scared of her, even though they are much bigger than she is. "These are why I am," she writes in her journal. "And in those moments, I knew how Hunter Rose saw. I knew it because I felt how they saw him. And in the end, this is what will save me: the irrationality of their fears ... my purpose ... direction ... belief in myself ... and my usage of Grendel. I knew what he saw." She still calls it "usage" even as she relates more and more to what Hunter Rose was like. She focuses her anger on the police, but Wagner, ironically perhaps, doesn't give her much to be actually angry about, even though we remain sympathetic to her.

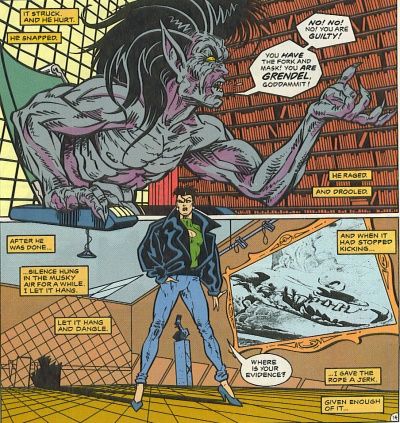

What do I mean? "Grendel" returns because Christine wanted to find her son. She takes the law into her own hands, steals Hunter Rose's trappings, and tracks Tujiro down. While the inactivity of the police in finding Anson is frustrating, there's nothing deliberately diabolical about it. In San Francisco, she does kill Tujiro's bodyguard and several of his troupe members, and despite the fact that Tujiro is killing young boys and running a slavery ring, Christine has no evidence of their crimes. If we look at it from the police perspective, we have a woman who is distraught over her son's disappearance and kills random people to assuage her grief and rage. The police who persecute her - a San Francisco cop named Dominic Riley, and a New York cop, Captain Wiggins - are certainly brutes, and Riley does beat Brian up, which enrages Christine, but it's still not enough for her response. Throughout the book, Wagner makes us wonder if Christine has, in fact, gone insane, or if she's justified in her response, or if "Grendel" is directing her actions. As she falls deeper and deeper into her anger, Grendel takes more and more control. This is what's frightening about the comic, not the fact that a vampire is stealing children's eyes.

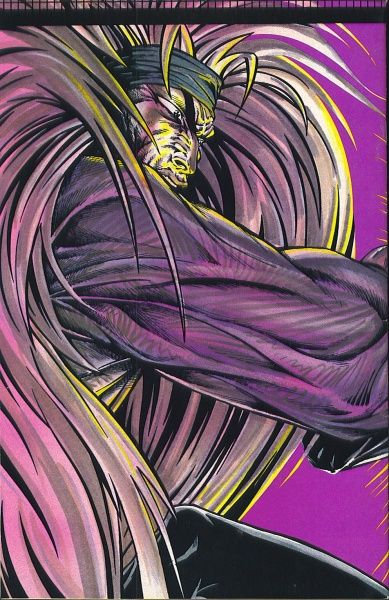

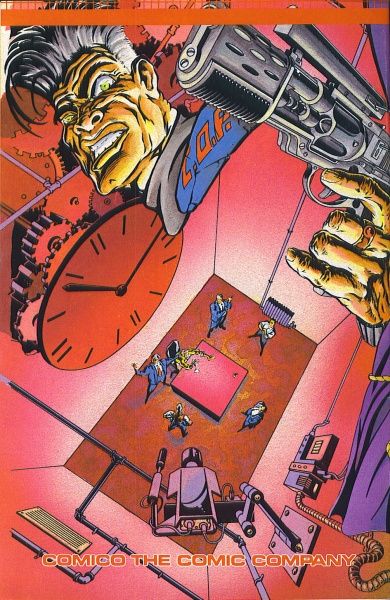

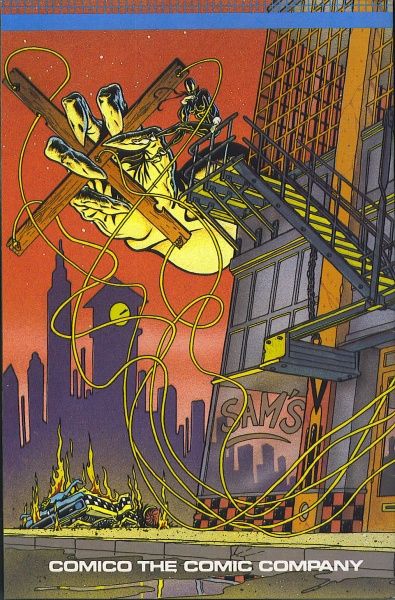

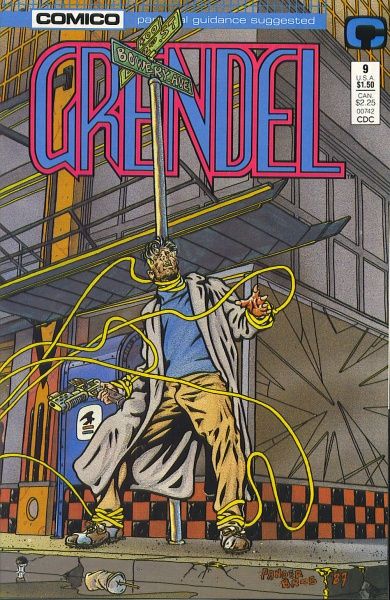

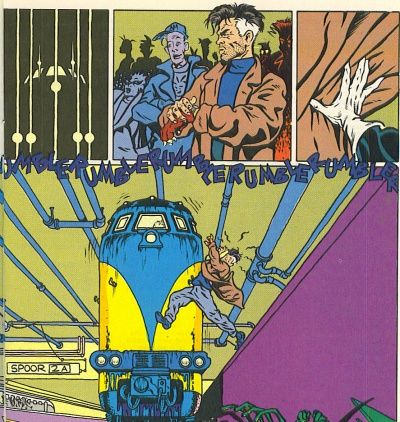

As we've seen, Grendel takes control early on, but we don't really begin to realize how far gone Christine has gone until the wonderful issue #9, "Devil's Revenge." At the end of issue #8, Dominic Riley followed Brian to New York, where he's gone to see Christine despite warnings to stay in San Francisco. Riley pistol whips Brian, whichnaturallypisses Christine off. Issue #9 begins withChristine's narration: "And as to the problem with Dominic Riley ..." and then, Wagner and the Panders take us on a 26-page silent odyssey in which Christine stalks her prey. It's atour-de-force of cat-and-mouse, as Riley sees Grendel everywhere, growing more and more paranoid.Christine puts hot coals in his coat, but he can't find her. A sign breaks loose from its moorings and almost smashes into him. She pushes him in front of a train but a good Samaritan yanks him back just in time. He grows more and more desperate, until she finally catches up to him. On the last page, with Christine standing over his body pulling the fork out of his chest, the only sentence in the book concludes: "... eventually,I killed him." It's an astonishing issue, not only because of the way Wagner and his artist collaborators create gripping tension without words, but because it's the first time we realize that Christine has completely gone over to the dark side. Riley was a punk cop who abused his power, true. But he hadn't actually done anything that warrants this kind of response from Christine.We cheer for his fate, becauseweloathe him, but when we consider his actual "crime" andhow she deals with him, it's far more chilling. This is a woman who has gone too far. Once she kills Riley, it's too late for her. Argent wants her too badly.

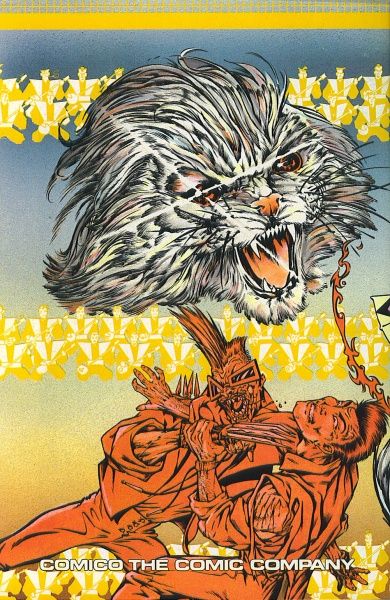

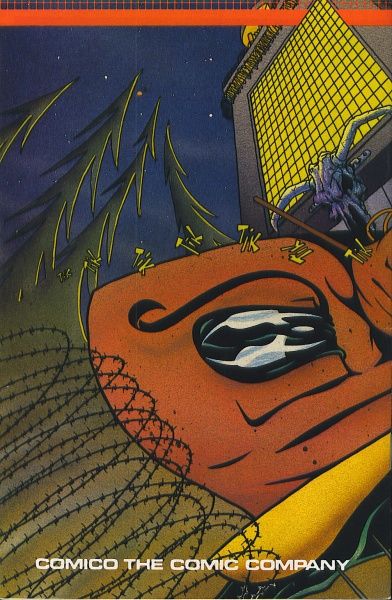

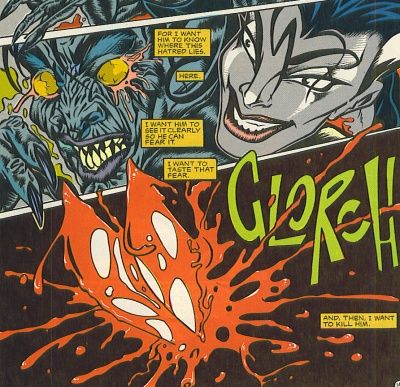

Riley's death sets up the final confrontation withArgent. AlthoughWagner doesn'tgive us much information about Argent, in the earlierseries, Hunter Rose asks him who he is, and Argent, we learn, is a 300-year-old NativeAmerican who was cursed by a wolf god. He is drawn toviolent acts, and hemade criminals his targets so that he could exist in society.It's interesting to contrast Argent to Grendel, because without being tooobvious about it,Wagner makes it clear that they are two sides of the same coin. Argent needs to fight, andhe focuses on criminals because before he was cursed he was a pacifist. Therefore, violence is repellant to part of his personality, but he still needs to express it.He focuses onGrendel becauseGrendel - as Hunter Rose - was the perfect criminal. Ironically, Christine is also cursed andalso needs to express herself violently. Shedoesn't understand that she and Argent are reflections of each other until the very end, and then it's too late. Both characters are bound by something far greater than they, and once Christine has made her choice, Grendel is in control. It all leads to the final bloody confrontation.

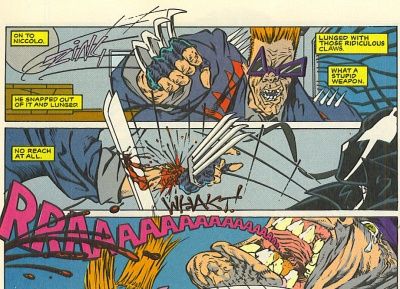

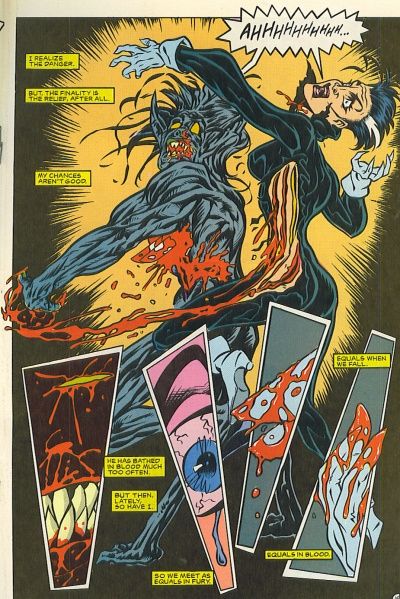

Christine kills two policemen who are following her, then fails to kill Captain Wiggins (which will become important in later issues of the comic). She then enters Argent's brownstone and, in issue #12, they fight to the death. It's a beautiful ballet of blood, really, expertly drawn by the Panders and punctuated with Christine's journal, in which she finally realizes what she has become and what Argent is. She writes, "It almost feels as if I'm going to kill a lover," and she's not far wrong. When Argentbreaks her weapon, she narrates, "If I am unarmed ... I am still deadly. I must remember that. I still clutch this hate. I still cling to my desperation. I am committed. I am driven. I am Grendel." At the end, she embraces what she has become, and although this ultimately kills her, it allows her to kill her old enemy too. As she picks up the two blades from the floor and drives them into Argent's chest, he rakes his claws across her body, nearly gutting her. Her narration is powerful: "I realize the danger. But, the finality is the relief, after all. My chances aren't good. He has bathed in blood much too often. But then, lately, so have I. So we meet as equals in fury. Equals in blood. Equals when we fall." Brian, Regina, and Wiggins all arrive at the brownstone simultaneously, Brian holds Christine as she dies, and she says, "S-so many ways ... that I loved you. So many ... ways to ... lovvve -" At the end, Christine rejects Grendel and Brian knows that everything she did was not out of vengeance, but for love. Her fierce love for Anson spurred her to "pretend" to be Grendel, and her love for Brian allowed Grendel to take over, because she didn't know how to handle saving him. Grendel is a powerful force, and it makes her into a force, ultimately, for good. Hunter Rose became Grendel not out of love, but out of a lust for power. Despite his love for his ward, Stacy Palumbo, it wasn't enough to save him, because she also cared about Argent, and their rivalry twisted Hunter's love. Christine is able to save her soul because of her love for her dead son and for Brian. When she kills Riley and goes on her vendetta against Argent, we wonder if she will be able to cleanse herself. With her final words, we realize that even though Grendel dominated her mind, it wasn't able to completely corrupt her. Her story is sad, of course, but it's not a complete tragedy. She is able to gain a measure of redemption, because her Grendel wasn't born completely of hate.

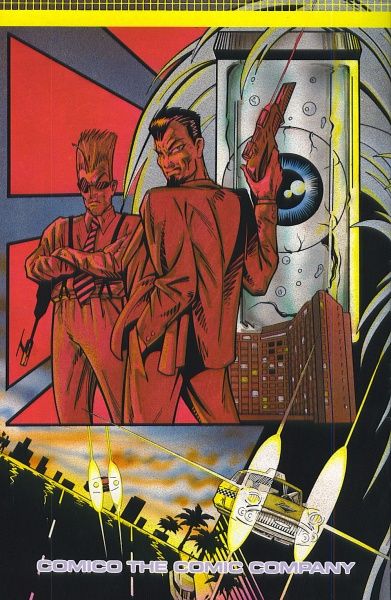

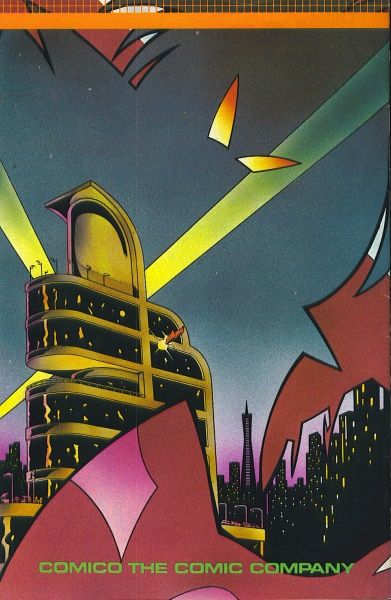

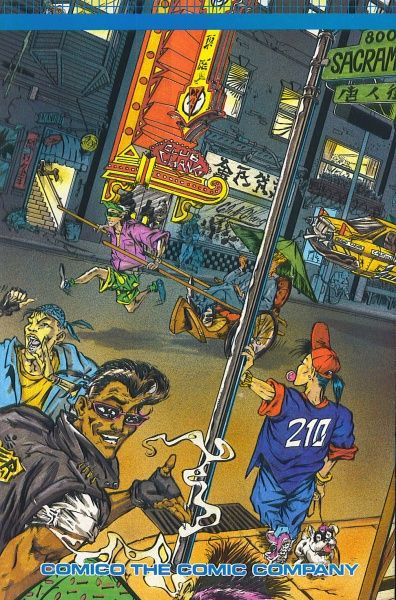

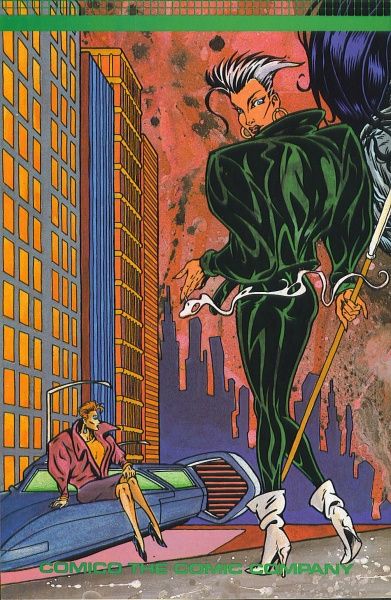

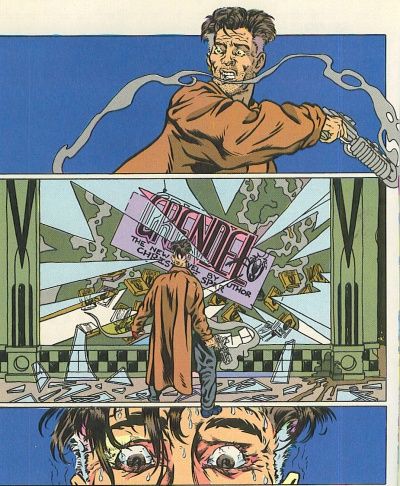

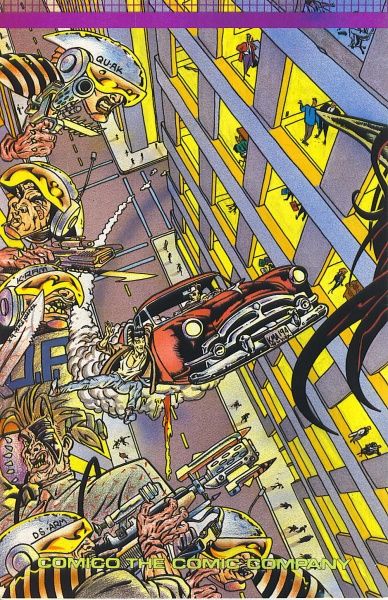

Part of the reason this book is so great is the Panders' art. I have heard in the past that many people were not happy with the art, because of its odd tone, especially when compared to the somewhat gloomy story. That's what makes it so perfect, however. The Pander Bros. don't allow this book to wallow in Christine's self-pity or the gruesome tasks of murder. Later issues of Grendel fell into this trap a bit and suffered somewhat for it. The Panders' pop art is magnificent, because of when Wagner sets the story, which is in the bright and shiny future. One of the letter-writers said it was 38 years in the future, which would put it around 2025. The world is certainly recognizable (and even dated; Christine has appeared on Donahue promoting her book about Hunter Rose), but Wagner wants us to contrast the futuristic and somewhat gaudy future with the rottenness at its core. Usually, in books with that theme, a writer makes that point. Wagner doesn't have to, because the Panders, with their flying cars and shining skyscrapers, take care of it for us. It shows the darkness even better, because we are used to an almost Jetsons-like reality, and the shock of the bloody battles Christine fights jerks us into them more effectively. The pencils are aided by Geldhof's inks, which keep the drawings slightly sterile and clean. We are in an ultra-modern world, and again, it heightens the ugliness of Argent while fitting Grendel's sleeknessperfectly. I'm not sure if it was by design, but when the Panders ink themselves, in issues #7, 9, and 12, they create slightly grittier drawings, with slightly more rendering and looseningof the lines. These three issuesfeature the two big fights - the confrontation with Tujiro, the battle with Argent - and themurder of Dominic Riley. The themes of the issuesare rougher, and the art reflects that. Issue #9, especially, is full of grotesque and horribleurban dwellers, wandering past Riley and creating this strange world where he (as the cover reflects) is but a puppet on Grendel's strings. The Panders, with their rougher inks, make this issue far more disturbing than it might be with Geldhof's cleaner inks. In the issue, they create images of Grendel's mask that stalk Riley as Christine does, with lights on the approaching train and headlights on cars lengthening into the familiar eyes of the devil. It'struly a wonderful effect.

One lastreason the art needs tobe ultra-modern, almost art deco, is because of the nature of Grendel.Hunter Rose and Christine did not rely on brute strength to kill. Hunter was a world-class fencer, and Christine studies kendo.When she fights, it's almostballetic, and the stylized art of the Panders fits that perfectly. The panellayoutshelpwith the frenetic feel of the art, and the drawings feel razor-sharp and graceful, which is how Christine fights. When they ink their own work in issues #7 and 12, Tujiro and Argent become true monsters, and her final battle with Argentrequires a paradoxical feel: beautiful brutality. The Panders are up to thetask. It's a stunning work of art and afantastic synthesis of writing and drawing.

Wagner took Grendel in a new direction following this issue, and the comic became something even more mythic. The seeds of his epic were planted in this magnificent comic book, and even though the later issues of this series will be the next post in this series, they never quite achieved the focus of these twelve issues. That's understandable, as Wagner was doing something different and needed a bigger scope. The series lasted until issue #40, and then resumed for a 10-issue coda years later. Then Wagner was done with the character (for a time) and passed it onto other writers. He has returned in recent years to Hunter Rose with a few mini-series by various artists, and soon he'll return to the art chores on an eight-issue mini-series about his original Grendel. Before you buy that (and you really should buy it), you can track down the trade paperback of this comic (it's still in print, and has been recolored, apparently) and tear into it. It's excellent.

As always, you can consult the archives of Comics You Should Own. I'm still waiting to hear on the fate of the ones whose links have vanished!