More Kaped Krusader Kraziness! Who doesn't love the Dark Knight?

Batman by Doug Moench (writer), Kelley Jones (penciller, issues #515-519, 521-525, 527-532, 535-552), John Beatty (inker, issues #515-519, 521-525, 527-532, 535-552), Eduardo Barreto (artist, issue #520), J. H. Williams III (penciller, issues #526, 550), Jim Aparo (penciller, issues #533-534), Mick Gray (inker, issues #526, 550), Bill Sienkiewicz (inker, issues #533-534), Adrienne Roy (colorist, issues #515-518), Gregory Wright (colorist, issues #519-525, 527-533, 535-552), Pat Garrahy (colorist, issue #526), Lee Loughridge (colorist, issue #534), Android Images (separations, issues #523-552), and Todd Klein (letterer).

DC, 38 issues (#515-552), cover dated February 1995 - March 1998.

Some SPOILERS below! Very few, though - I tried to keep away from them!

It's early- to mid-1994 in the DC offices. The Bat-editors are sitting around, wondering what they're going to do when the big "replace Batman with a crazy person" crossover is over.

They have Dick Grayson lined up to take the mantle of the Bat for a few issues, but after that, what can they do? Everyone wants Bruce Wayne back because Azrael, let's face it, sucked as Batman, but who can they get to write and draw the continuing adventures of everyone's favorite dark and disturbing vigilante? Someone (Denny O'Neil, maybe?) says, "How about we get a writer who has become increasingly more paranoid about the government and honestly seems to believe that aliens landed in New Mexico in the 1940s and are currently influencing our culture, and team him with an artist who excels at making everything he touches look more grotesque than Bosch? And why don't we put these guys on our flagship title, Batman?" And they all look at him briefly like he (or she, I suppose, depending on who was there) is insane, but then, slowly, the idea takes root. Sure, why not? Let's do that!

Doug Moench and Kelley Jones on Batman is one of the weirdest pairings at one of the weirdest times in comic book history. Remember, this was the mid-1990s - when image (and Image) was everything, and comic books were all about barrel-chested men and large-breasted women spouting things like "We must defeat Dr. Large Pecs, or Our Way Of Life will Forever be Altered and We'll be Trapped in an Alternate Reality where 7-11 never invented Big Gulps! Oh, the Horror!" DC wasn't immune to the "new way" of doing comics (namely, sucking all of the fun out of them) - witness the Death of Superman and the Breaking of the Bat, but to their credit, once that monstrous piece of crap had worked its way through the bowels of the executives at DC, they gave us this. And comics became better.

Moench has been around comics for years. He cut his teeth on Marvel titles in the 1970s before bringing the first iteration of Moon Knight to glorious light in the early '80s, teaming with some fella named Sienkiewicz. Those MK stories were excellent (the subject of a future column), and they were also where Moench started to get a little skeevy about the government. He wasn't a full-fledged paranoid yet, but the road was in front of him. He moved on to Batman and Detective in the mid-1980s, a not-bad run (mostly because of Gene Colan's art), but he did try to expand Batman's supporting cast, fleshing out Harvey Bullock (sorry for the pun), although I don't think he created him (comments to the contrary are welcome). Alas, he tried to turn the two main Batman books into a running soap opera, like the X-books, and failed. After that I lost track of him. Then, DC gave Batman back to him. First he did some Elseworlds graphic novels in which our friendly neighborhood Bat-guy becomes a vampire. Who knew his predilection for the supernatural would follow him to the mainstream? He had also become a writer who looked completely askance at anything the government did, had apparently studied either some science or whatever Warren Ellis reads about science, and had honed his writing skills even more. DC turned him loose, and he gave us wild new villains while also showcasing the old ones.

Although Moench's scripts are wild, they would have lacked the punch of the bizarre without Kelley Jones. Jones, at this point, was known for a few things: the "Calliope" story in Sandman (he did other issues, too, but this one is the famous one), a couple of Deadman series with Mike Baron, and the aforementioned Elseworlds Batman vampire OGNs.

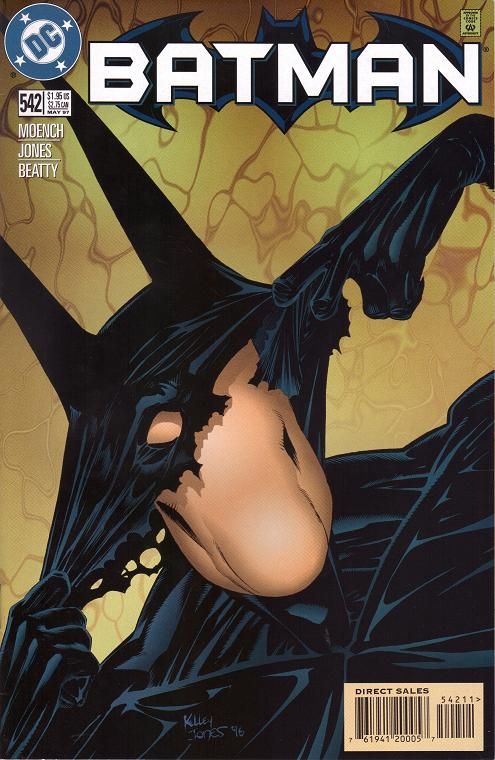

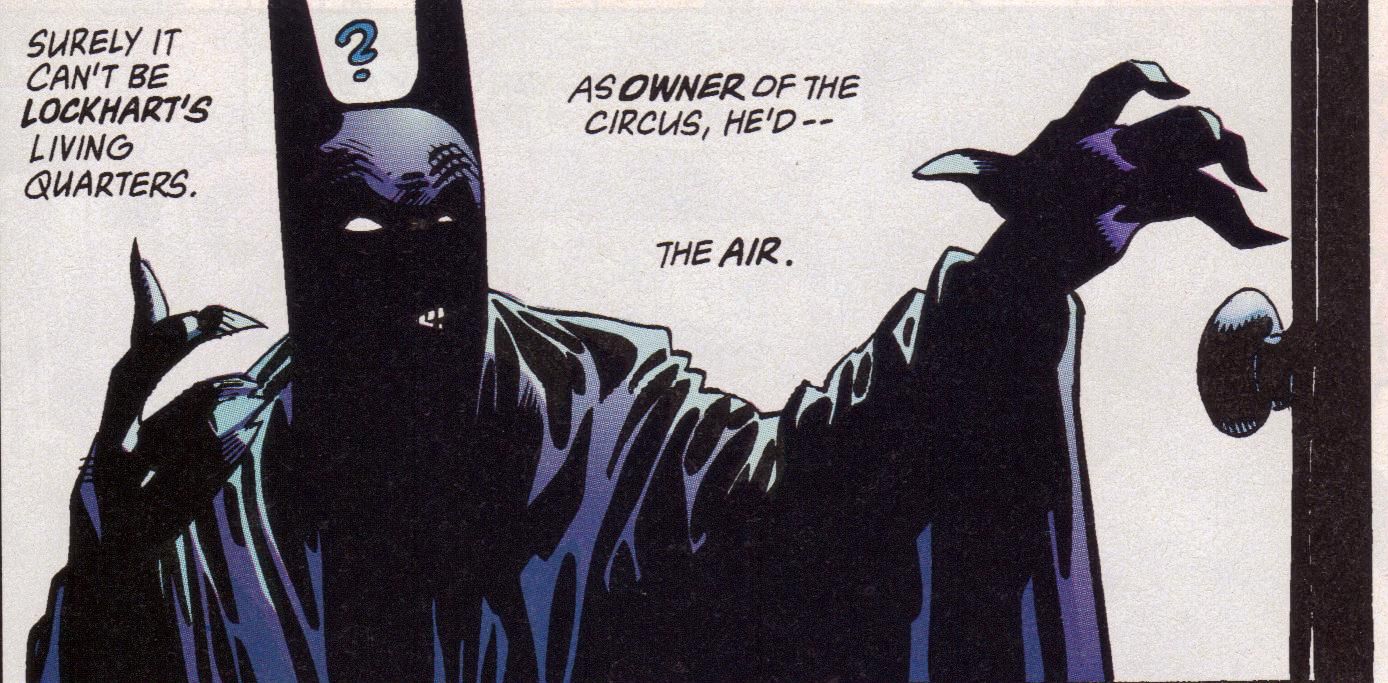

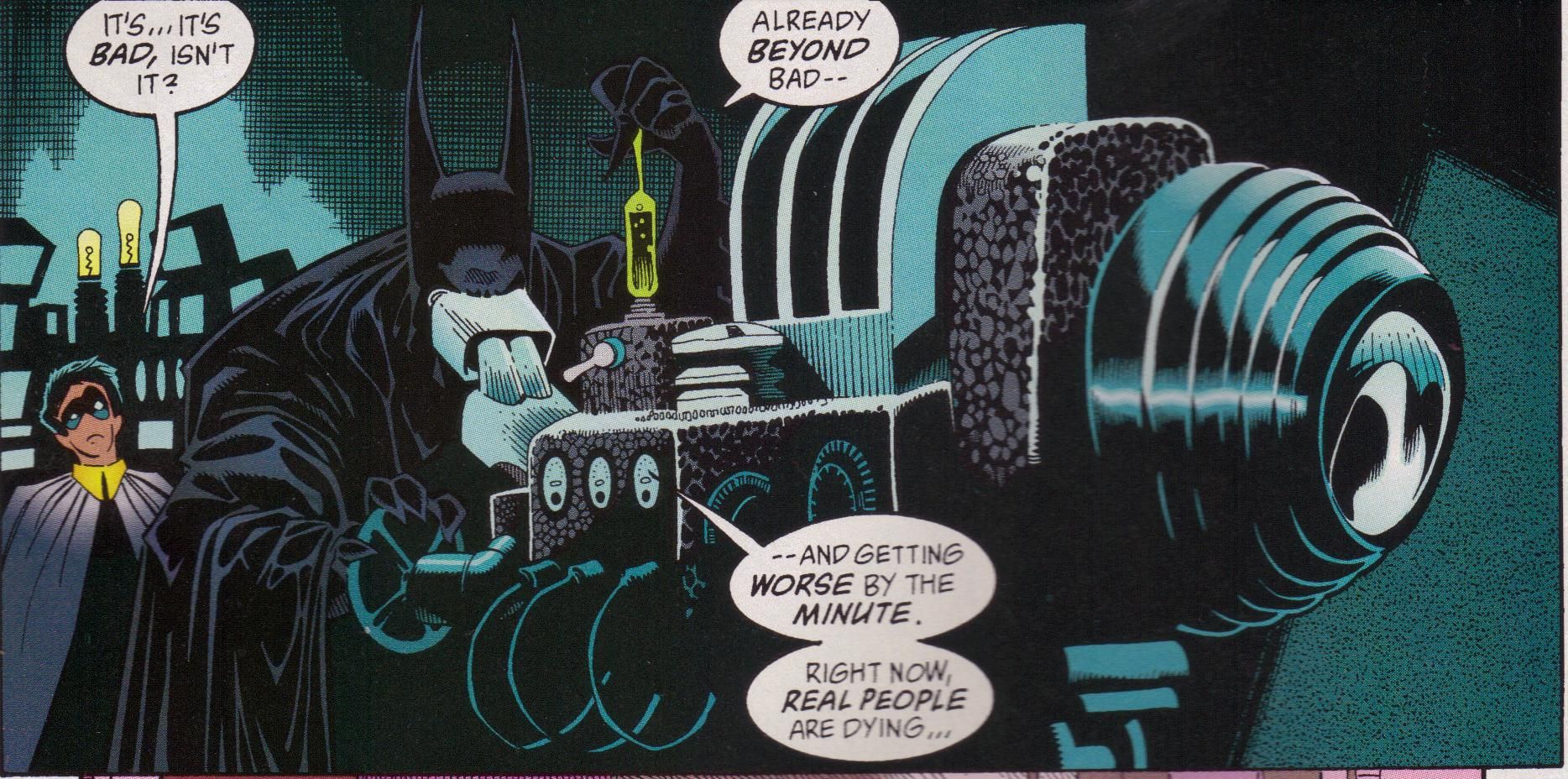

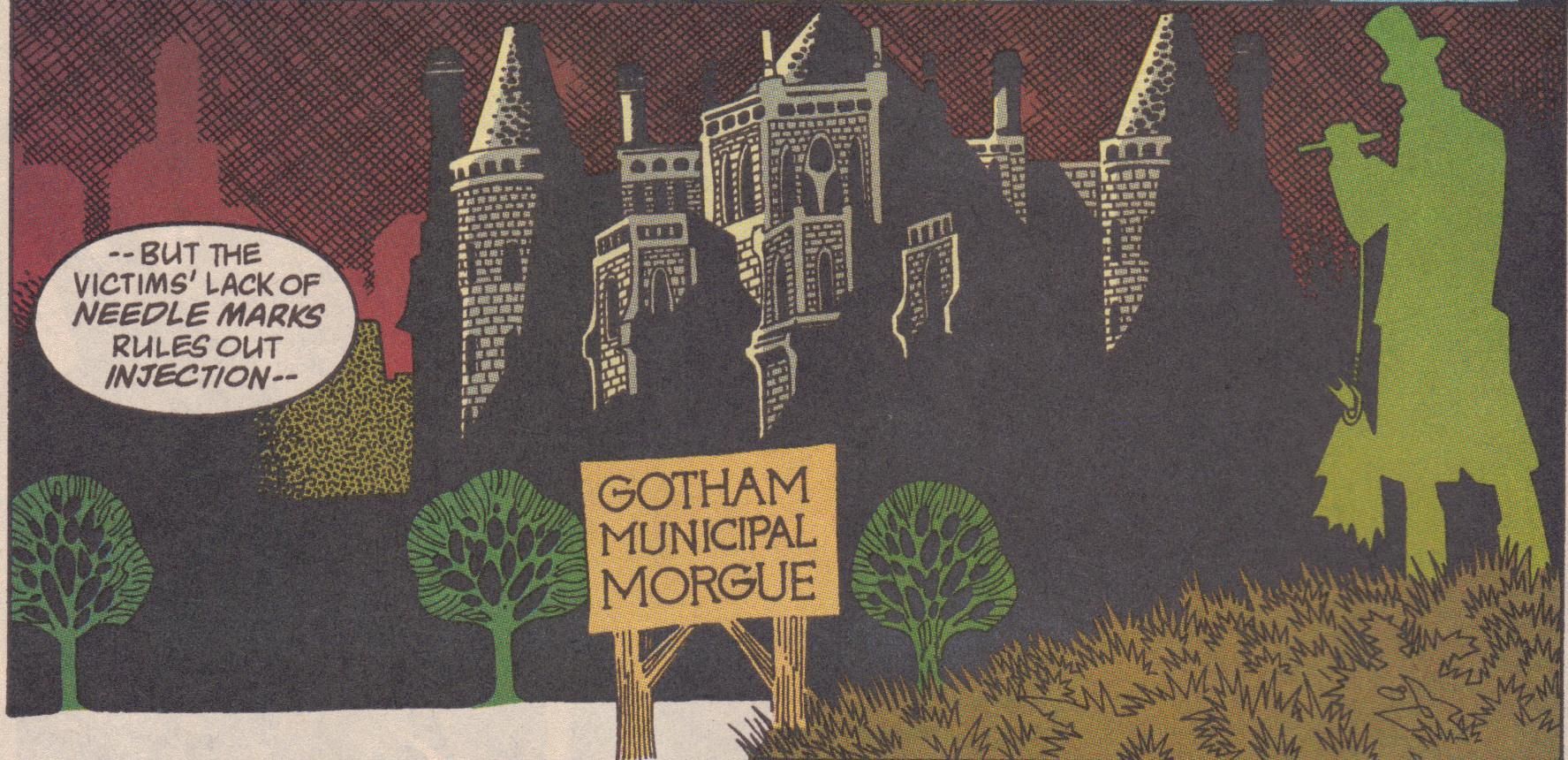

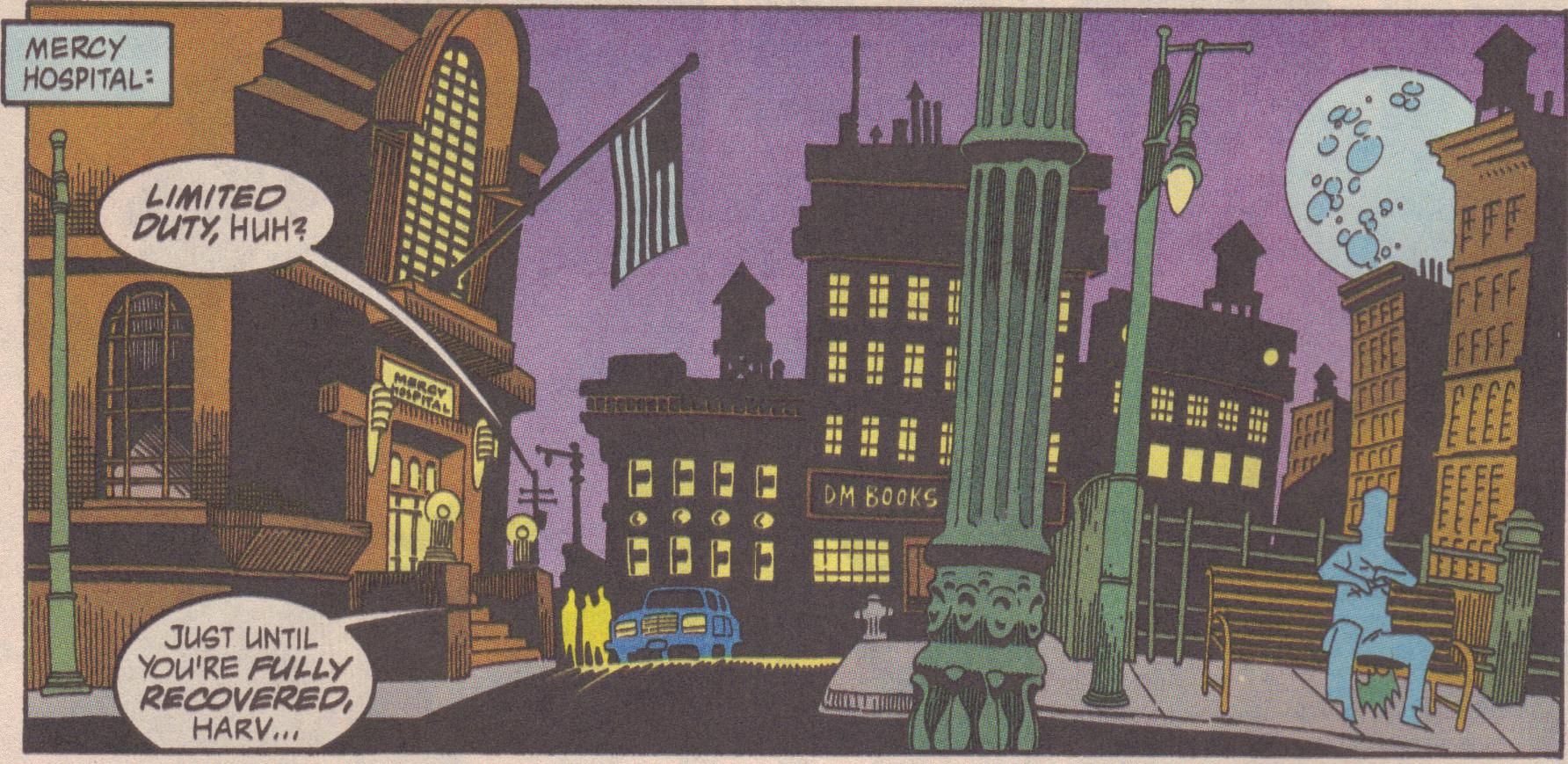

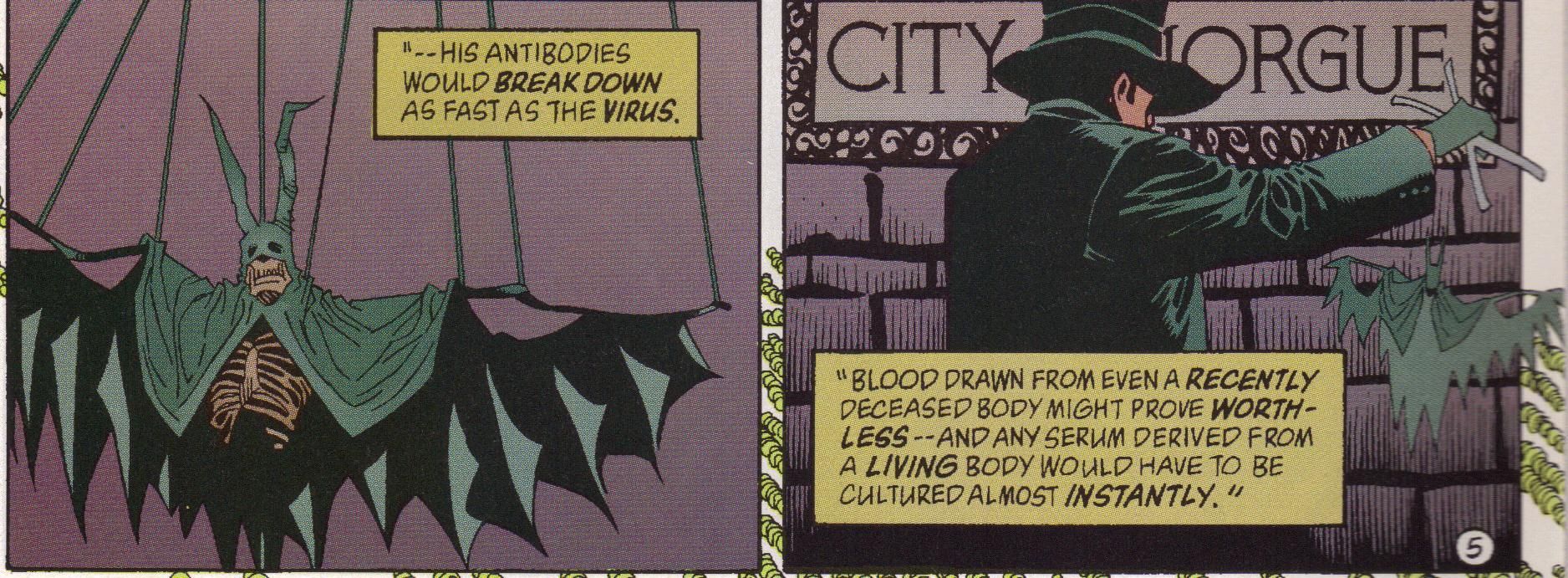

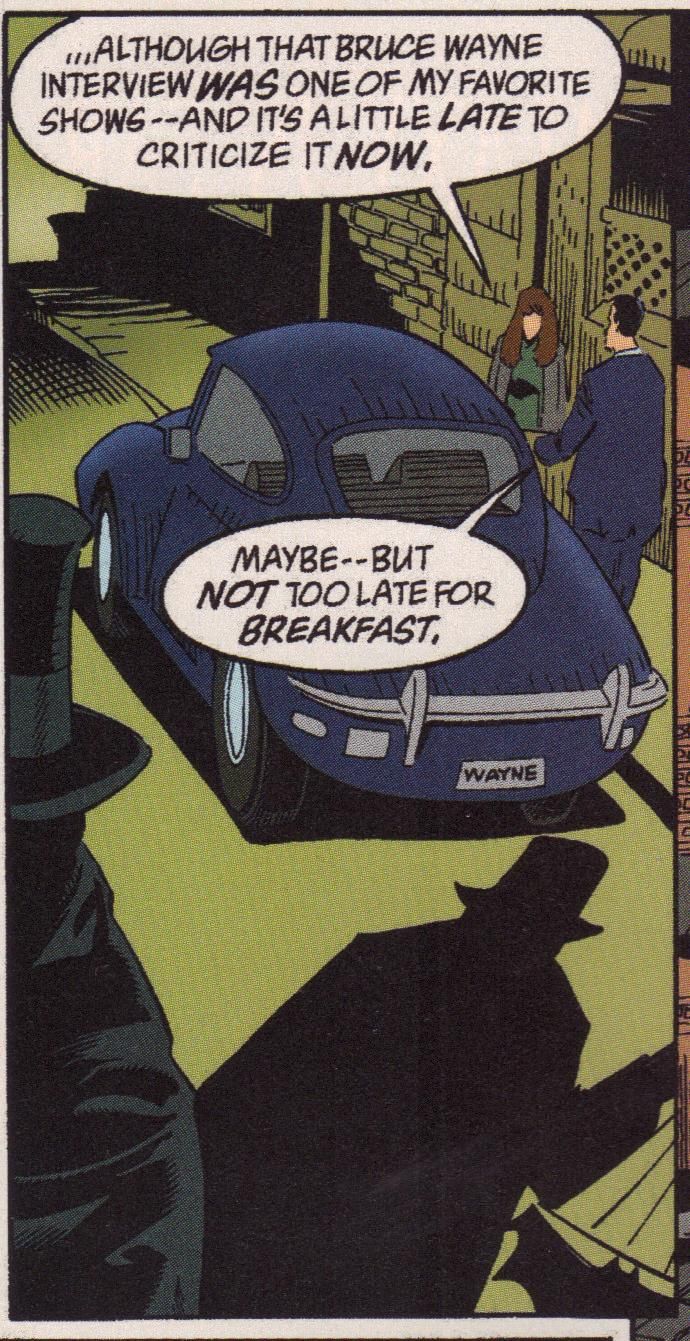

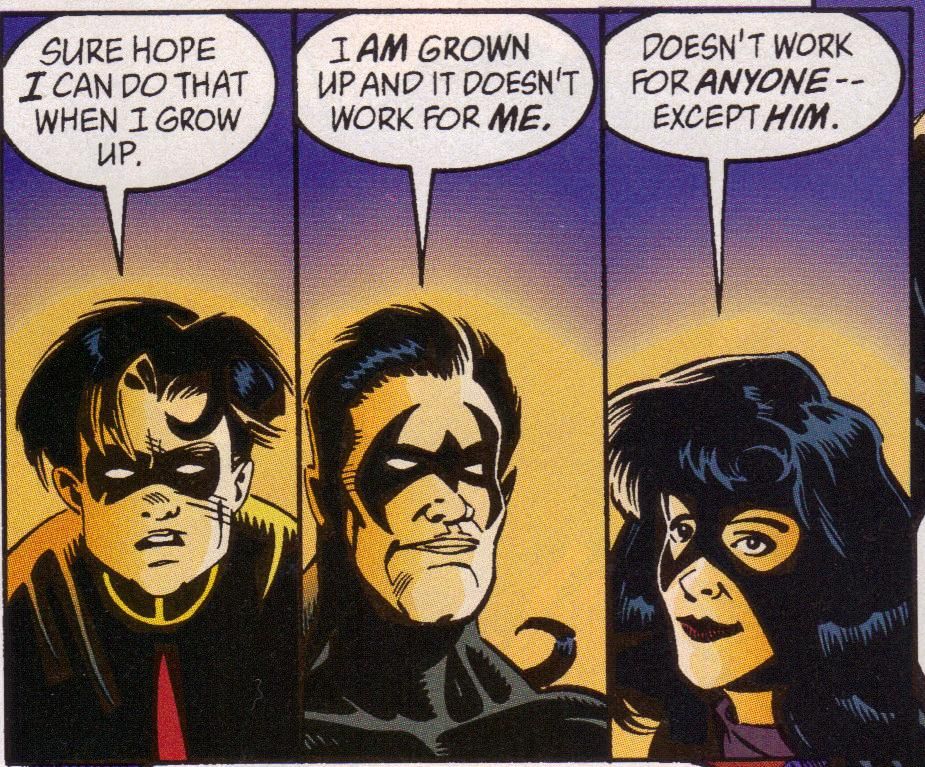

He must have had a friend at DC, because one thing Jones is not is a typical superhero artist. That's perfectly fine, even though my perception was that Batman was always the more "superheroic" of the main titles, and that's why people like Jim Aparo always worked on it. Jones took Moench's weird scripts and turned Batman into a visual feast. This was a truly gothic Gotham City - cobblestones, weird spires, shuttered windows, narrow, winding streets, ornate streetlights - this was a city in which not only evil, but weirdness lurked. This was a city in which Batman's old-school, 1930s-style Batmobile that Jones redesigned (until he started using J. H. Williams' design in the latter part of the series) wouldn't seem out of place, and would come out of a fog bank and scare the jumping bejeesus out of even innocent bystanders. This is a Gotham in which the coroner, the delightfully-named Mortimer Gunt, could stew in a basement off the set of a Hollywood horror movie - when you read the autopsy scenes, you can almost hear the creaking of the gurney wheels. In short, Jones made Gotham terrifying. But he also made it a city with more personality than it usually has. I mentioned in my last column that Peter Milligan made Gotham a character in his three-part story, "Dark Knight, Dark City." His city, however, was sentient. Moench and Jones' Gotham isn't alive, but it's no less a personality. Jones also turned the denizens of this weird city into gargoyles, quite literally. A small but vocal fan base wrote in to complain about, of all things, the length of Batman's ears. Sheesh. Jones' Batman was grotesque in all the right ways - his ears extend upward out of panels occasionally, and he is often twisted and hunched over, with claws for hands. The rest of the cast becomes horrific, too. The aforementioned Mortimer Gunt has a bulbous head and sunken chin, and looks for all the world like one of the corpses he's cutting up. Harvey Bullock becomes an obscenely fat cop, a stereotype in every way, which makes Moench's humanizing him during the run more interesting, because Jones (deliberately, I'm sure) draws him like a caricature. Some of the villains are cartoonishly drawn, and in many instances this is a good thing - Jones' Scarecrow is truly eerie, more so than usual. Even the "normal" people in the story - Gordon, Alfred, Sarah Essen, Tim Drake (who looks like a drag queen in one memorable panel), Vesper Fairchild (whom Moench created during this run) - often look askew, as if inhabiting a slightly off-kilter universe. Ironically, the only person who ever looks "normal" is Bruce Wayne, when he shows up. It's an interesting little tic that Jones has - it's as if he's trying to say that Bruce Wayne is the rock of stability in this wild universe he has created, but because Bruce is often absent, the world has gone bizarre without his influence.

The stories are all short, three-issues-or-fewer arcs, but Moench is still trying to turn Batman into a long-running soap opera. Therefore, we get recurring themes and consequences, even though the stories resemble your standard Batman stories - villains show up, Batman smacks them down, they are forgotten. Moench is interested more in the relationship between Batman and not only his supporting cast, but the villains as well, and therefore the villains' schemes are not really that important to the overall stories. It's worth pointing out, however, since this is a long run, how it's broken down:

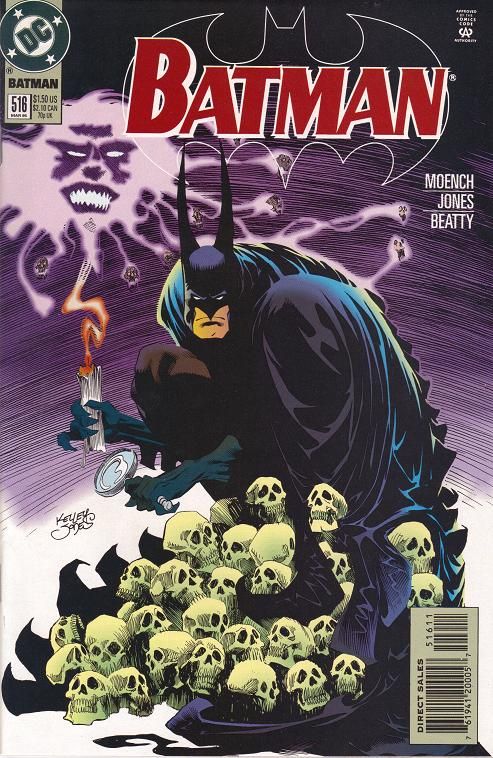

Issue 515: The first part of "Troika," re-introducing Bruce Wayne as Batman and giving him a new costume, which isn't really all that different. The Dark Rider, from Moench's run on the titles in the 1980s, is the main villain. This story is continued in the other Bat-titles and is a nice introduction to Jones' work, but doesn't really pop off the page like the rest.

516-517: The Sleeper story. Moench shows that he has been reading far too many conspiracy theories and stories about government experimentation.

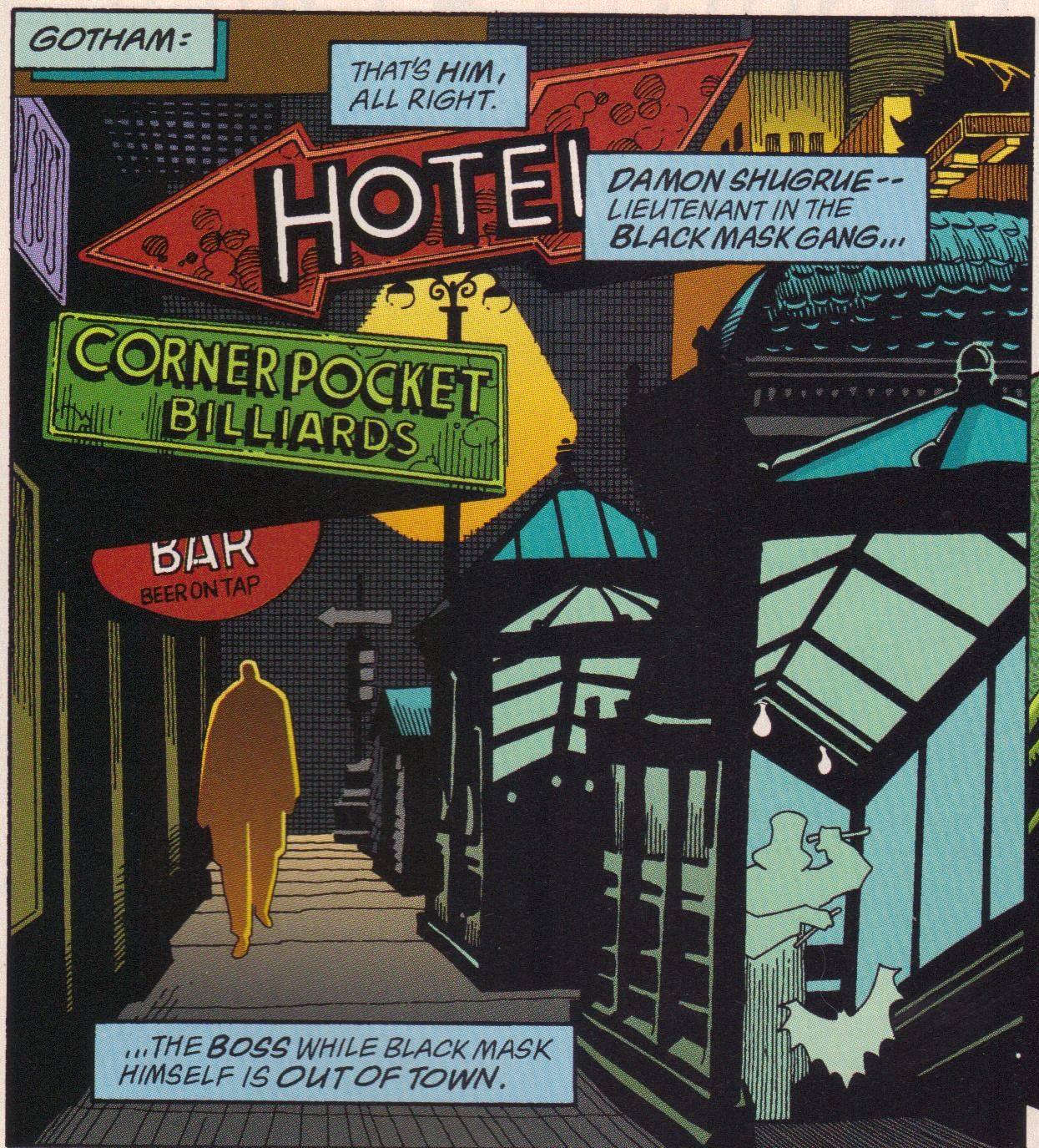

518-519: Black Mask and Black Spider. Black Mask was always an interesting villain. These days, apparently, he's just another crazy guy.

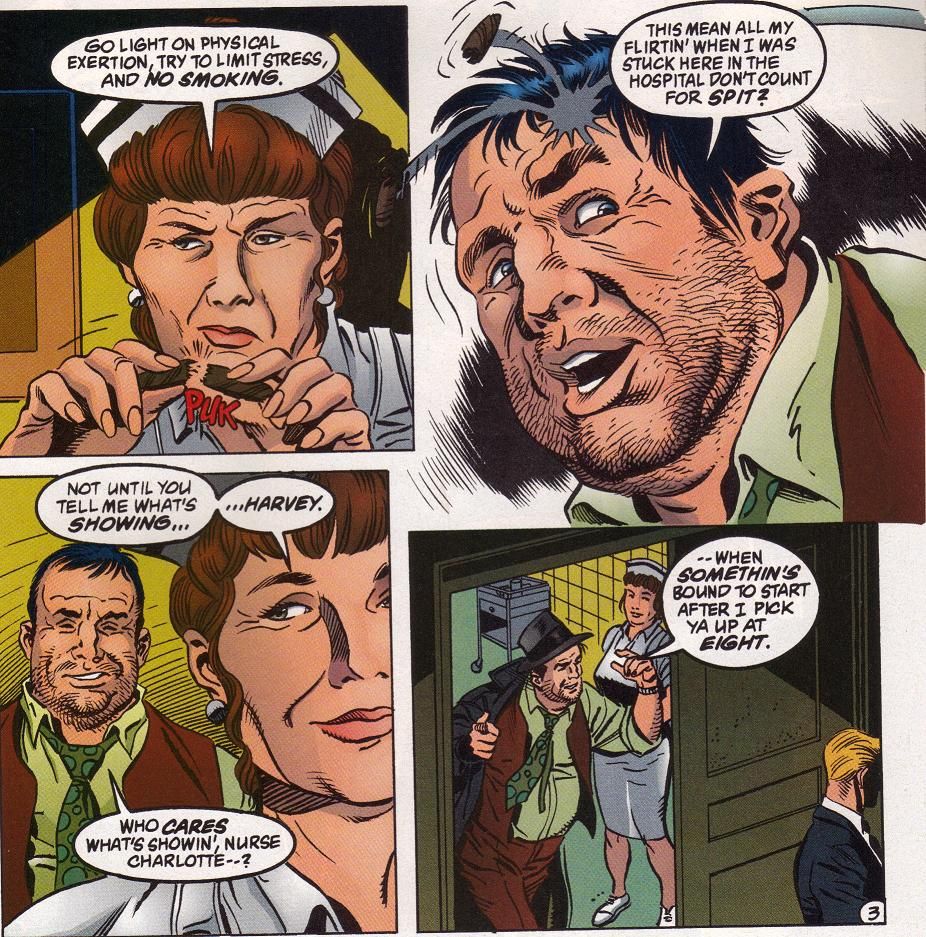

520: Eduardo Barreto illustrates a "human interest" story in which Harvey Bullock gets a date. Since it's the Batman Universe, no good can come of it.

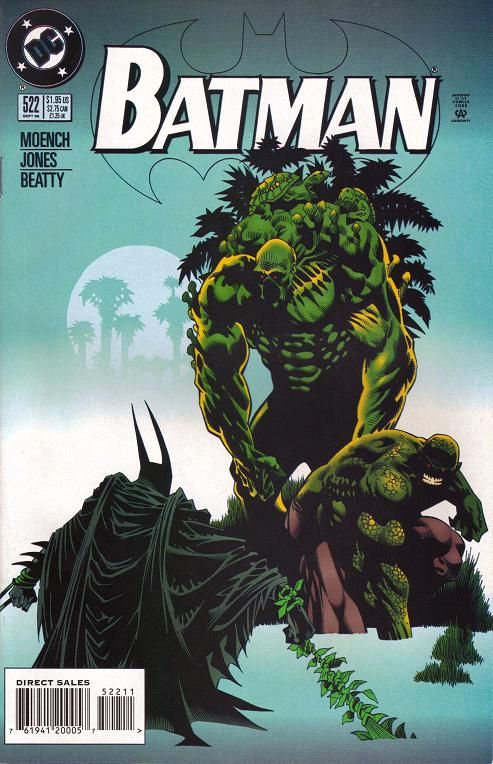

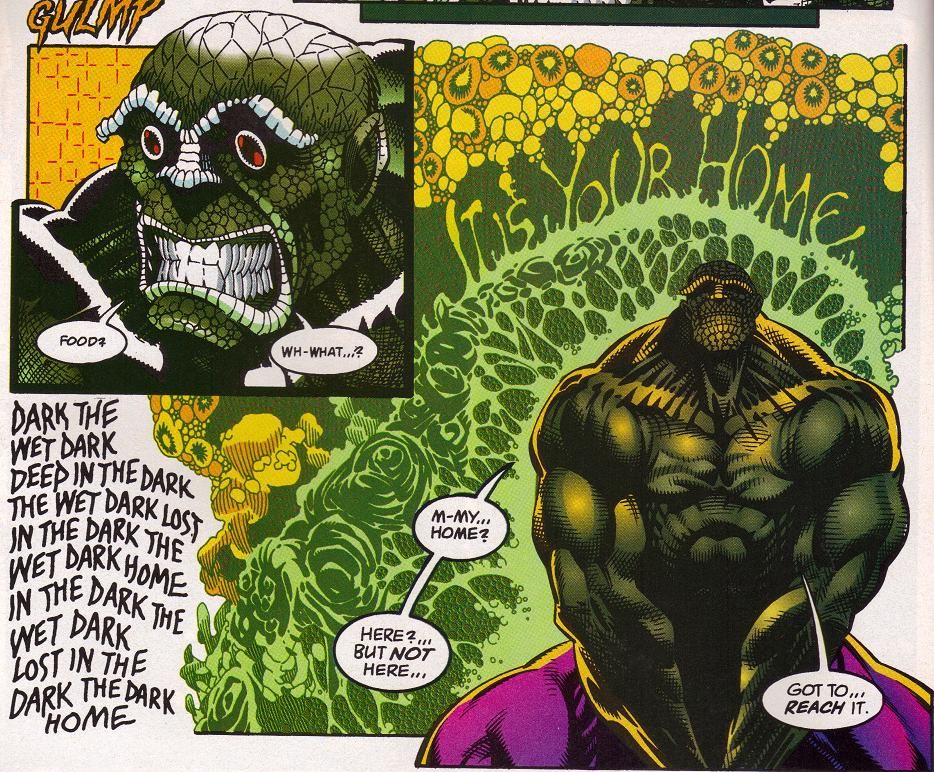

521-522: What should have been the last Killer Croc story. Guest-starring Swamp Thing!

523-524: The Scarecrow returns. Moench re-did his origin in an annual around this time, and incorporates elements of that into this story.

525: Mr. Freeze shows up in an "Underworld Unleashed" story. Like the best of these related stories (the "Major Disaster" one in Aquaman), it's only tangentially related to the big storyline.

526: J. H. Williams III illustrates a story dealing with "constant whitewater" - Bruce's seeming inability to get downtime. It's an interesting peek into his psyche.

527-528: A Two-Face two-parter in a circus. Jones in his element.

529: Poison Ivy shows up as part of the "Contagion" crossover. One of the weaker efforts by the team, simply because it's part of the crossover.

530-532: Deadman guest stars in a weird story that takes Batman to Peru to deal with gold smugglers and lost Incas. Moench begins getting really experimental with storytelling techniques, as we'll see.

533-534: Aparo and Sienkiewicz illustrate parts of the "Legacy" crossover. It's always good to see Sienkiewicz inking anyone, much less Aparo, but these two issues have nothing to do with the rest of the run.

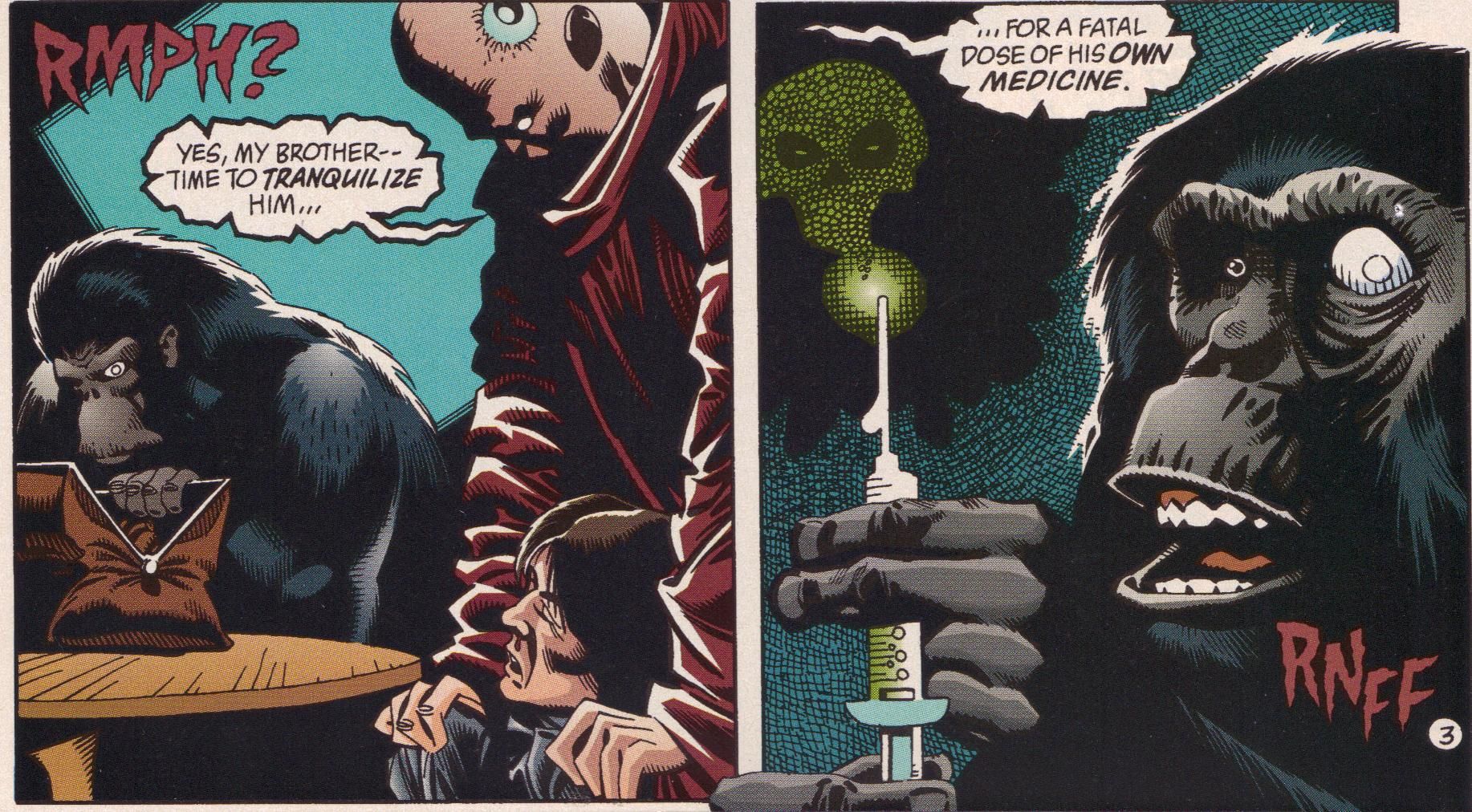

535: The double-sized "Ogre and the Ape" story, in which Moench allows his mistrust of government full rein.

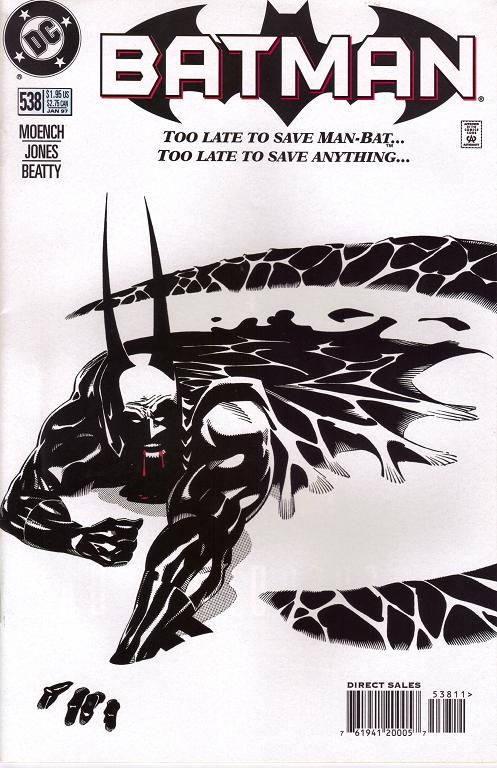

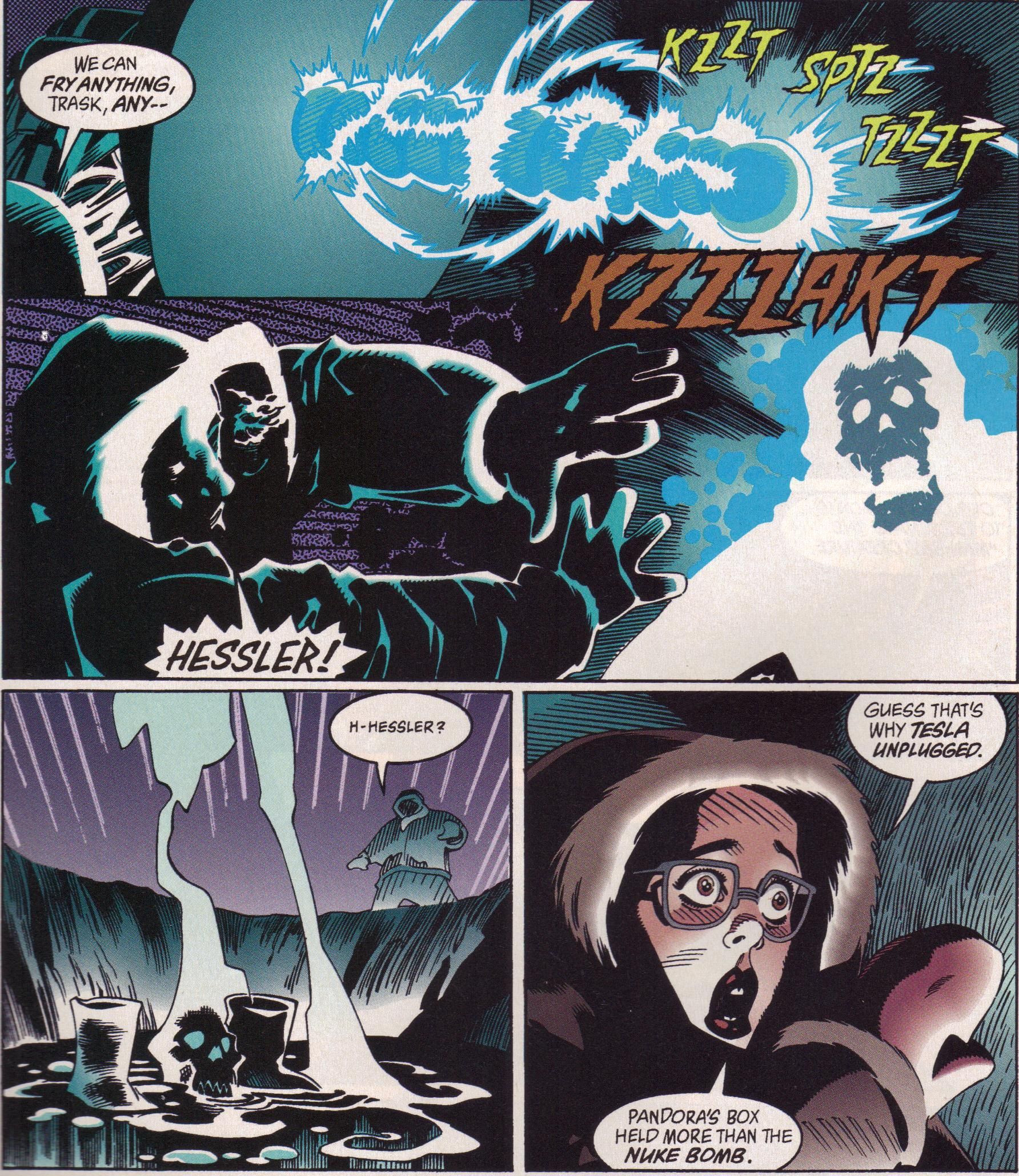

536-538: Man-Bat appears as part of the "Final Night" crossover (in issue 536) and flees to the Arctic, where Batman must track him down. More governmental shenanigans.

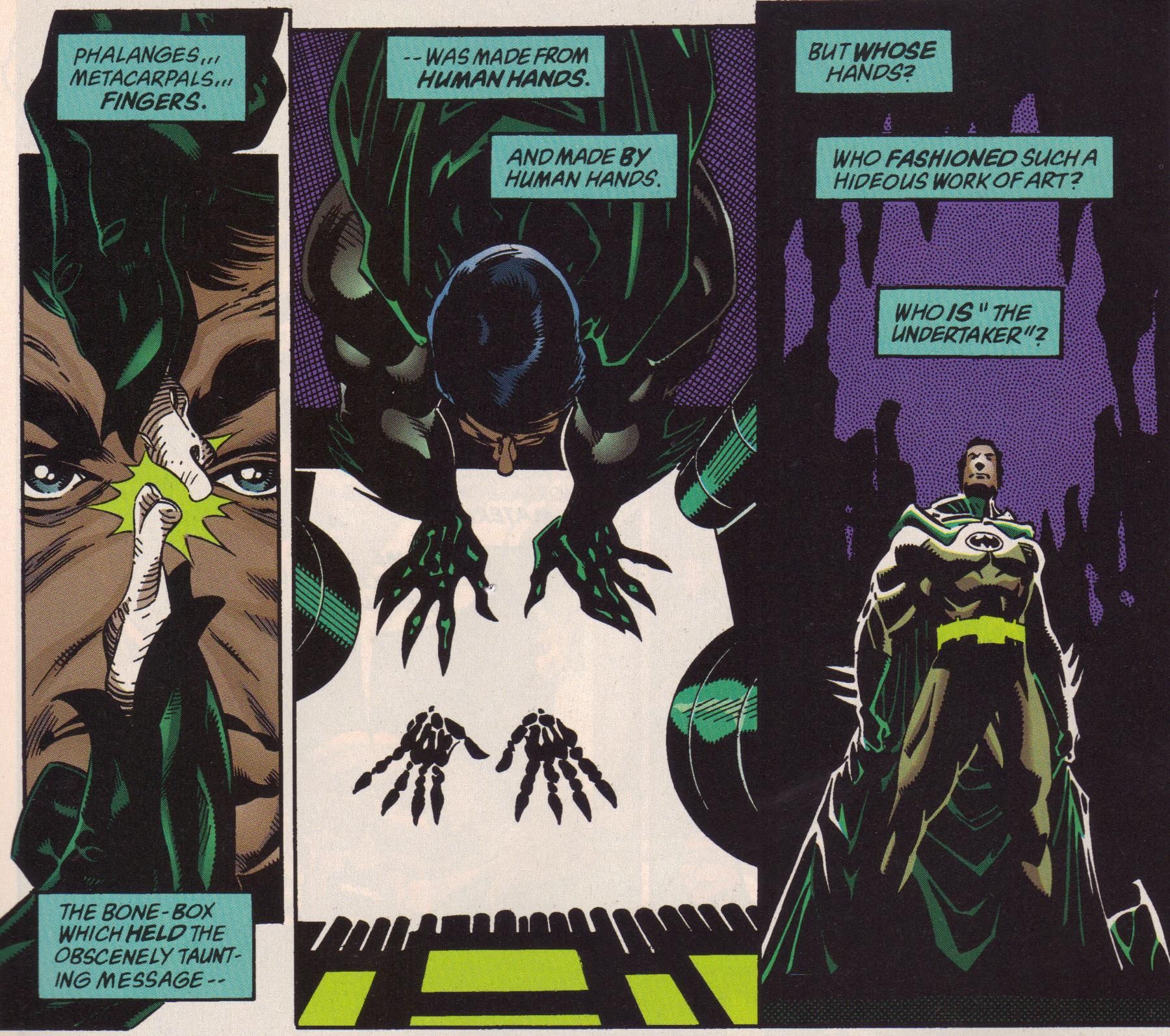

539: A new villain called the Undertaker is doing naughty things with dead bodies. Come on, it's a DC book - nothing too icky!

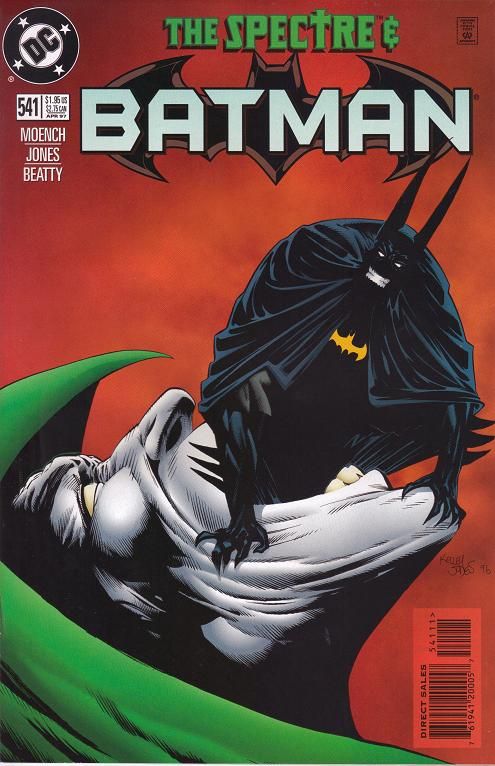

540-541: The Spectre guest stars and Bruce gets a new love interest - Vesper Fairchild!

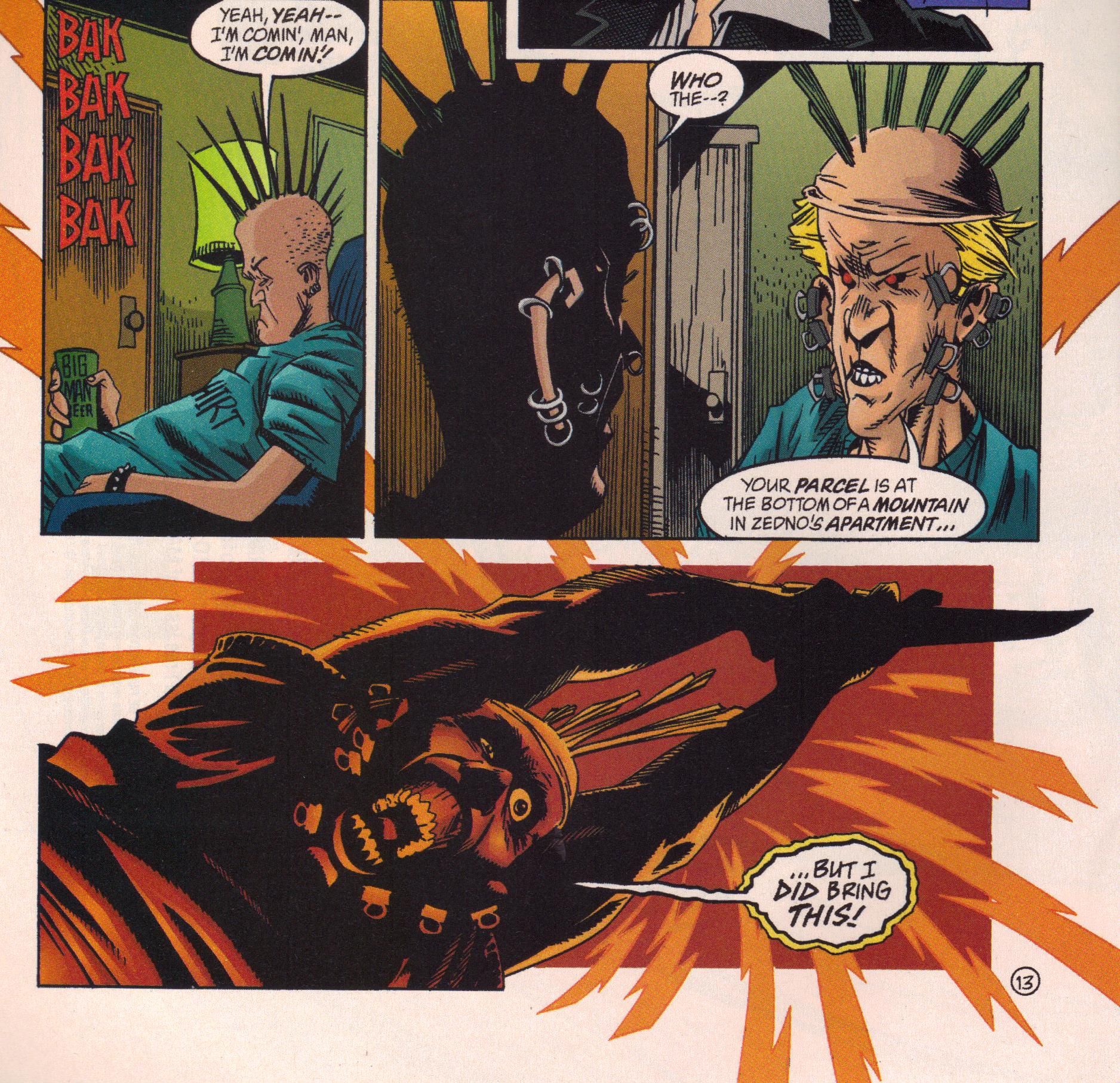

542-543: Moench mocks the whole "crazy mailman" theme with a story about Faceless, a, well, crazy mailman.

544-546: The Joker summons Etrigan to do his dirty work. You'd think this would be a slam dunk, but it might be the weakest story in the entire run.

547: A pseudo-crossover with the whole "Genesis" thing. People are depressed and the heroes of Gotham (including the cops) must help them.

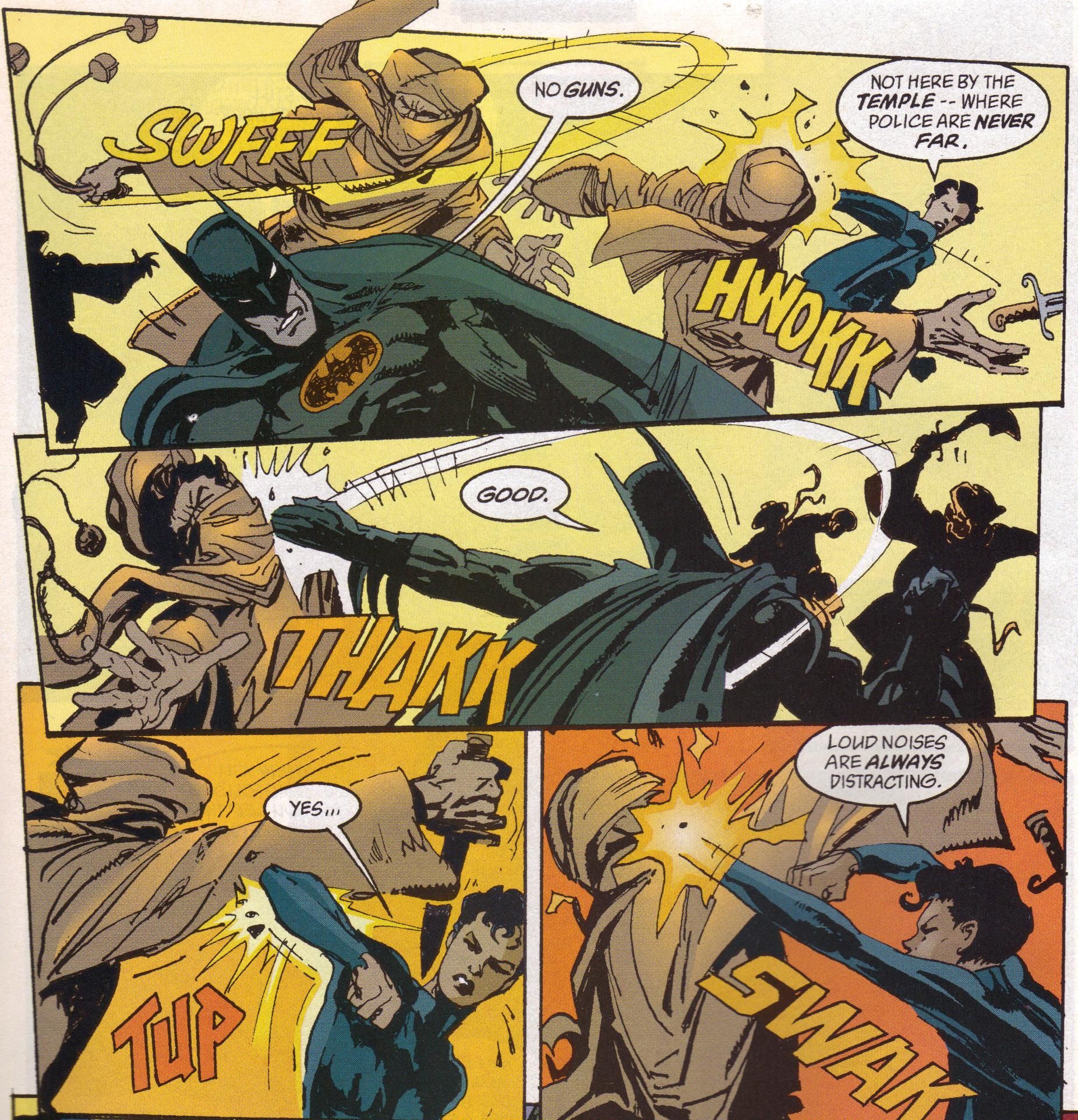

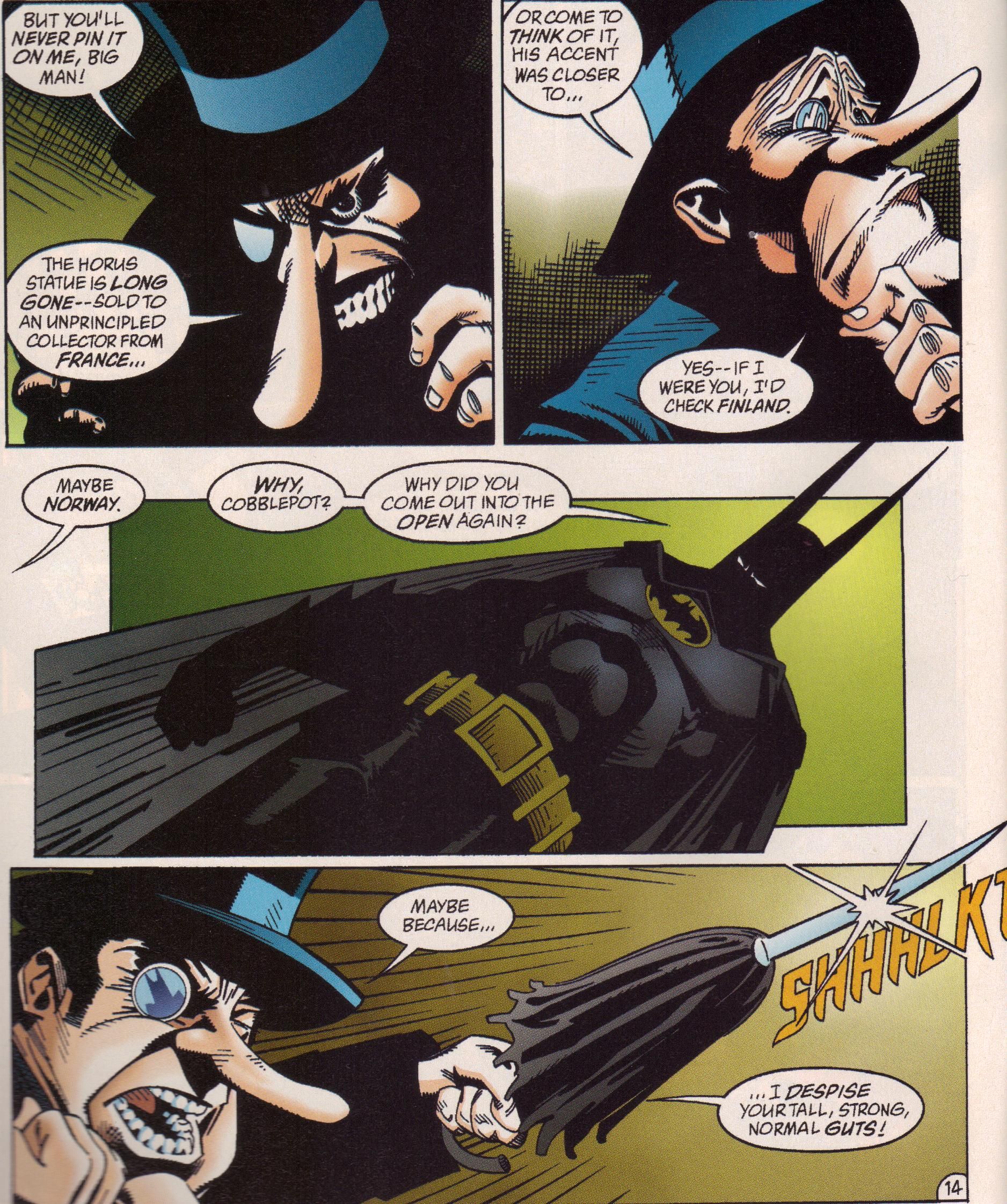

548-549: The Penguin gets tired of his casino and returns to crime. He doesn't get away with it, but he doesn't get caught, either.

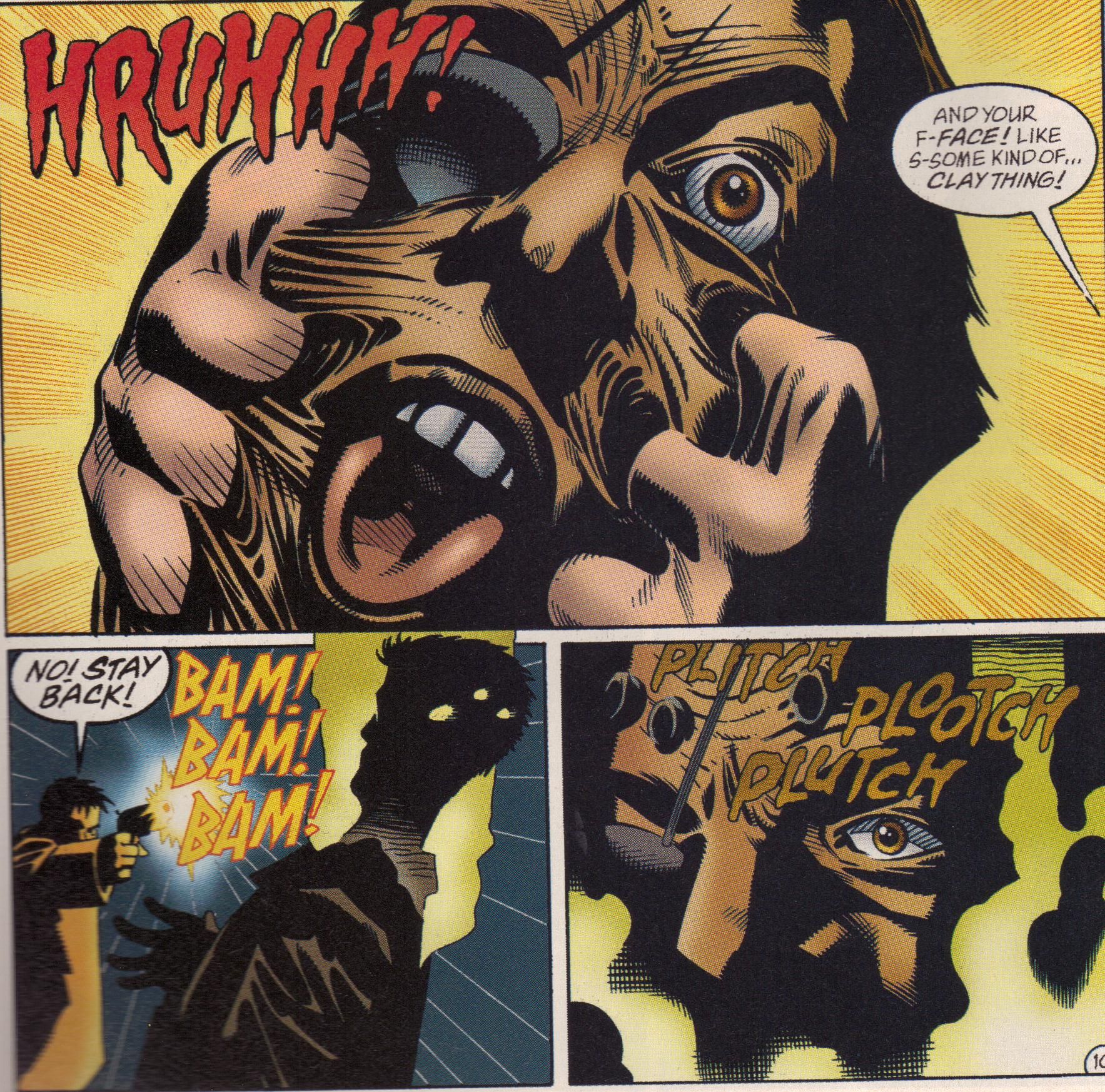

550: The introduction of Chase, in a Clayface story. Williams III pencils part of it, as an introduction, I assume, to her own series, which is quite good but died too quickly.

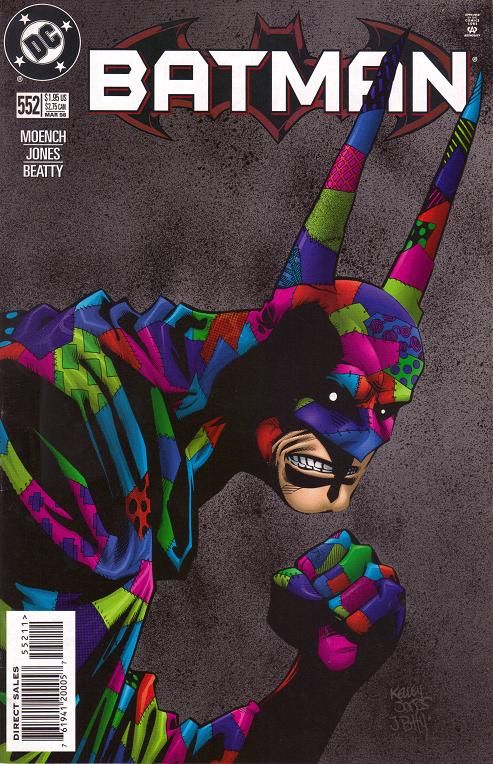

551-552: Ragman returns to Gotham and has some problems with his costume. Neo-Nazis are on the prowl for Jewish victims, and Rory and Batman must stop them.

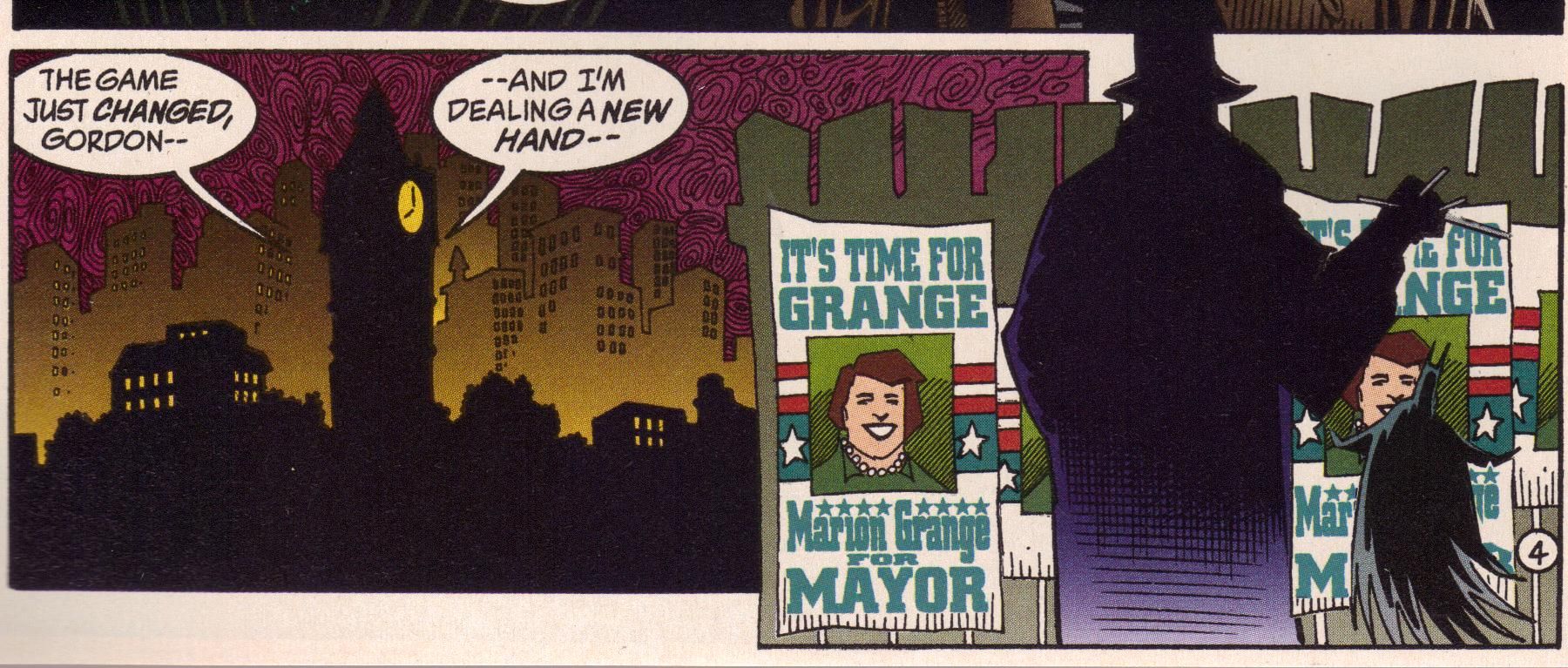

Moench gives us a nice mix of classic villains and creations of his own, which of course were ignored by later writers. He also gets into the various characters in a way that is all-too-rare in any comic starring our Bat-friend. He obviously has a soft spot for Harvey Bullock, but Commissioner Gordon's relationship with his wife (Sarah Essen, that is) is handled well, especially when she is chosen by the mayor to replace him. In the first issue of Moench's run, he promises more focus on Bruce Wayne. Obviously, since it's not titled The Adventures of the Playboy Millionaire, Batman is going to be the focus, but Moench manages to peek more often than most at Bruce's non-Batman life, especially after the introduction of Vesper Fairchild in issue #540.

Vesper was treated, well, horribly in later issues, culminating with her murder, but in the year that Moench wrote her, she is a fascinating love interest for Bruce, one who actually gets him to think more about his role as Batman and what it means, something no woman had done since Silver St. Cloud in the late 1970s.

The introduction of Vesper, the loss of trust between Gordon and Batman (from the events of the previous year, when Azrael went nuts), the interactions between the members of the police force, and the dynamic of the villains themselves, all cohere into a theme Moench explores constantly throughout the run: Masks and how they hide identity and how they change us. In any superhero book, the potential to deal with how the costume affects our identity is there, and several writers have run with it. Just because Moore did it in Watchmen doesn't make it a subject other writers can't tackle, and Moench does it in a different way than Moore did anyway. Batman, obviously, lives a double life, and that's why writers always have to write a Harvey Dent story when they take over Batman, to show the dichotomy and the similarities between the two. Moench takes it one step further, as Harvey visits a circus and meets up with conjoined twins, who share a middle eye but not a personality - they argue for most of the time they are on the page. Conjoined twins might be a bit obvious, but because Jones' drawings are so unsettling and there's a murder mystery in the middle of the story, we tend to overlook the link between Batman, Harvey, and the twins - the twins and Harvey representing the inner struggle that Batman goes through, although one character (Harvey) has taken the struggle to the logical extreme, while the twins are still wrestling with it.

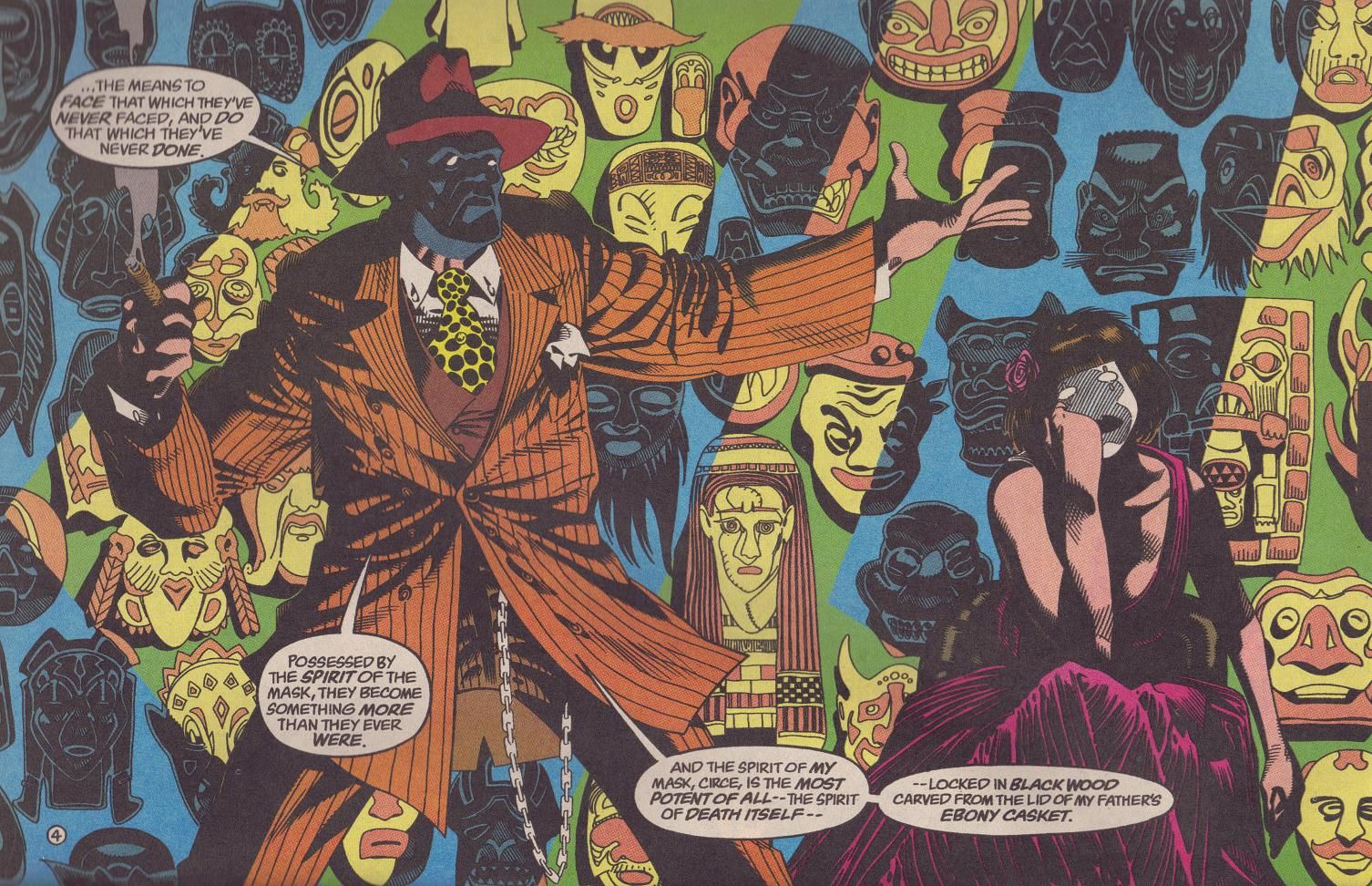

We see this idea of masks affecting and shaping lives in several other stories, as well. The Black Mask story, again rather obviously, uses this theme, but not really in dealing with Roman Sionis, who isn't the main character in the arc.

The main character is the clichéd 1950s greaser Johnny Lamonica, who wants to join the False Face Society. To do this, he has stolen the costume of the Black Spider (who is dead), and confronts the gang. Lamonica is a pretty boy, but his beautiful face masks his twisted personality. When he puts on the Spider mask, he laments covering up his gorgeous face, but we realize that the mask is his reality - ugly and disturbing. When, at the end of the story, his face is slashed by a broken window, that "mask," just like the burned face of Roman Sionis (much more disturbing than the current "skull" face he has) is fitting because he becomes a monster, inside and out. Masks give us power, of course, as Sionis himself says to his mannequin girlfriend, but the truly powerful (which Sionis thinks he is, even though he's not) are freer. "The secret of our masks," he says, "is that we don't need them." Moench makes the point here that even Batman is not powerful, because he needs his mask. It's a bold statement, because many other writers have tried to prove that Batman's mask is what gives him power. In a few simple lines, Moench disagrees, then spends the rest of his run proving it, as Bruce Wayne slowly comes out of the shadows and puts aside the mask more and more, gaining power all the way.

The issue of masks and identity continues to come up, because Moench is fascinated by it. He creates some notable villains, including the Ogre and the Ape and Faceless, that deal with this theme. The Ogre is a homeless man who is experimented on by shadowy government agents. They "devolve" him and "evolve" an ape in order to try to discover the missing link. The two escape and begin a vendetta against the members of the program. The Ogre loses his identity because of the experiments, becoming more like an ape, while the ape becomes more like a man. It doesn't even matter who he is anymore - just that he is no longer human. The "Faceless" story is the culmination of Moench's ideas about masks. Faceless is a mailman who is ignored by all the people on his route. He creates masks that mimic the people on the route and then kills them, "replacing" them with himself for a brief instant. At the post office, he is faceless - no one knows who he is.

On his route, he is faceless unless he screws up. So he decides to become these people, because he obviously has no identity of his own. It's not that difficult for Batman to figure out who is murdering these people, but again, that's not the point of what Moench is trying to say. He wants to examine what happens when modern life becomes so disconnected and diffuse that no one sees the people who are in our lives every day. People are losing their identities every day, and some of them will snap, especially in a place like Gotham City, which seems to actively destroy identity. In the final story of Moench and Jones' run, Ragman feels that he is losing his identity. For those who don't know about Ragman, he is a hero connected to Jewish legend who defends the innocent wearing a suit of rags made of souls. The suit is becoming evil in the story, as the souls are starting to exert their will. Ragman can't control the suit as it kills the bad guys instead of simply subduing them. Rory Regan (Ragman) feels that he is losing what makes him human - the ability to forgive. It is an inner battle that he has to fight, and ultimately he can't do it by himself - he needs the rabbi he visits and Batman to help him regain his humanity and, of course, his identity.

The second thing that makes Moench's run truly unique is his paranoia. I don't know if Moench lives in a bunker in the backwoods of Bucks County, PA, stocking cans of food and practicing his aim on squirrels for the inevitable day when the government comes to take away all his rights, but from his fiction, I wouldn't be surprised.

His Batman run is full of speculation about what shady things the government is doing, and it's of interest to look at why he does this. It starts in his first story, in which a woman named Sleeper is killing people and removing their hearts as, supposedly, a sacrifice to her "goddess." It turns out that she is being used by the government to kill the members of a group of scientists who experimented on her, depriving her of sleep in order to turn her into a perfect agent. This theme comes up again in the Ogre and the Ape story. In each of these, people are used by the government and then either turned against those who used them (in Sleeper's case) or who break out on their own and track down those who destroyed them (the Ogre). In both cases, Batman is obligated to stop them, because they are murdering people, but in both cases, our sympathy is with the so-called villains (in the case of the Ogre, Barbara Gordon actually begs Batman to stop the people who did it, not the Ogre himself) and we find ourselves rooting for them against the government agencies. Batman becomes less of an avenging hero and more of an audience to vengeance - he is unsure what to do about the crimes, because he recognizes the justice of them. In the issues directly following the Ogre and the Ape story, Moench brings in Man-Bat, who also gets involved in the government, this time in the Arctic. Some governmental types are experimenting with a new way to tap into the Earth's magnetic fields, and since it's the government, it all goes horribly wrong. In these stories, Moench is not only allowing his paranoia to run wild, but he is making an interesting comment on Batman and his place in our society. Many writers make the case that Batman exists to punish the criminals that the police can't handle, but it's rare (Frank Miller excepted, but that wasn't in continuity) for a writer to contrast Batman's vigilantism with the activities of the government so blatantly. Batman becomes the reader's substitute for our doubts and fears about a government that has very little to check it. Batman has always been, of course, the superhero we could be, since we could all, conceivably, train hard for the role, but in Moench's hands he becomes the guy who can stand up to the government. He doesn't win, of course, but he does bring to light some of the more nasty aspects of the abuse of power. The government wins because they have unlimited resources and can always sacrifice scapegoats, but we feel vindicated all the same. Unlike Miller in both Dark Knight series, this Batman's fight is ultimately futile, even as he wins individual battles. In the comic book world, the status quo must always win, but Moench can show that the victory is not the point - the fight is. Batman never backs down, and neither do those people whom the government has tortured. Because it's a comic book, Moench can allow his fantasies to bloom fully, and although one could argue that this cynical view of the government is unhealthy, it is less a realistic view of our own government and more of an idea of a powerful group that abuses that power because it can.

This is not the "American government" per se, just a government that has grown corrupt and knows that it can get away with things because no one has the courage to stop it. Batman has that courage, and he is our proxy in our continual struggle to make sure our elected officials remain honest.

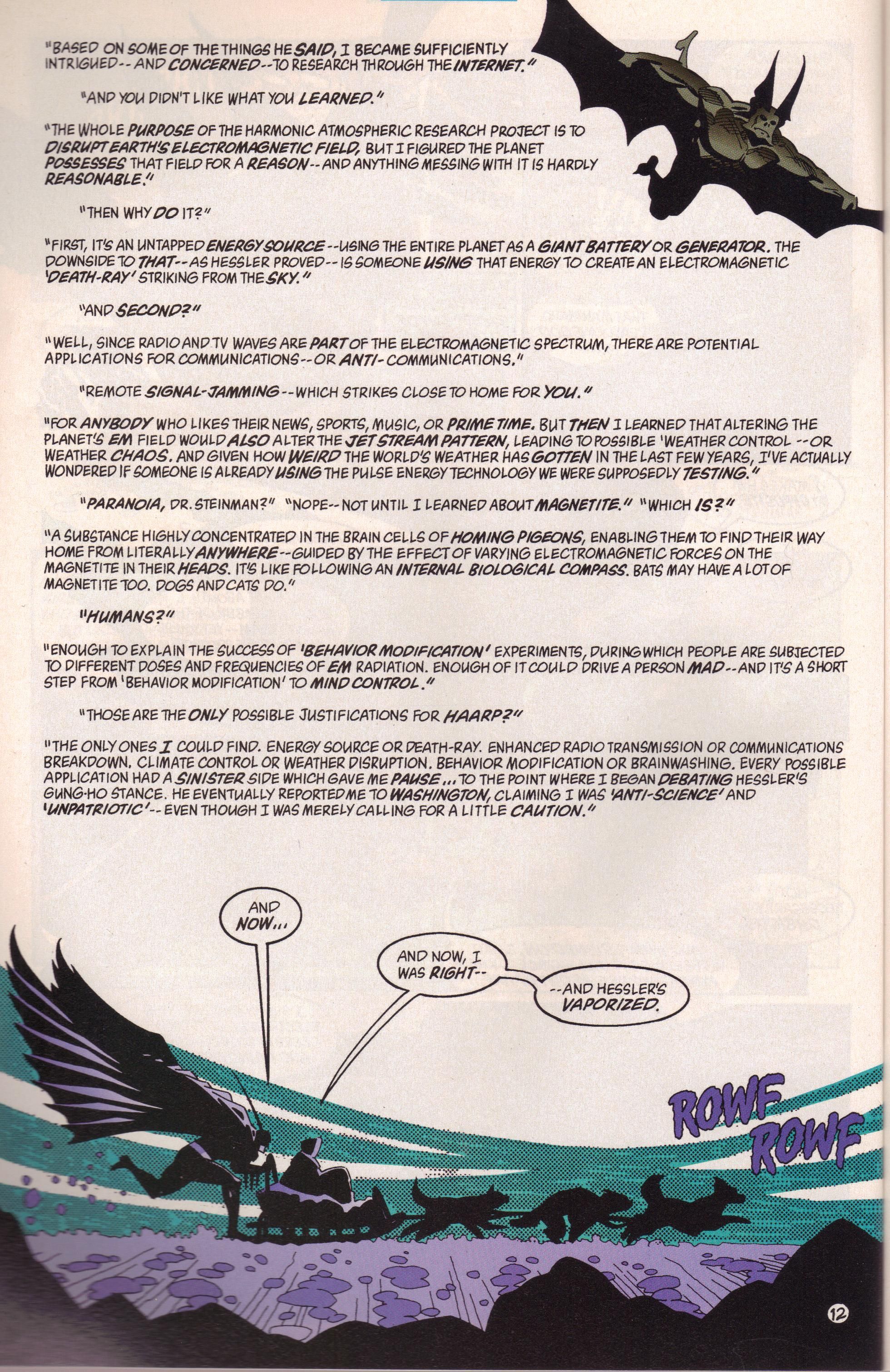

Moench also tries new things with his storytelling, another example of why this is a unique run on Batman and why it's astonishing DC gave it to these two iconoclasts. Moench has always been a didactic storyteller, and while it is usually in the context of the stories, he also likes to expound on his pet theories and new ideas he finds interesting. More than once he has two characters speak to each other as if they were at some sort of lecture, and although it can be frustrating to read, usually it fits in with the story and informs the audience. Moench's lecturing tone is in full view during this run, as he tries something we don't often see in mainstream comics - full pages given over almost completely to dialogue. The first time he does this is in issue #531, page 10, on which Batman and the Inca priest, Chimu, discuss whether Batman, who dresses like a demon, is evil, and why men commit evil acts. Batman and Chimu are both depicted on the page, but in simple poses - the rest of the page is given over to the dialogue between the two. He does it again in issue #538, page 12, while Batman is chasing Man-Bat across the Arctic and talks to one of the scientists about HAARP - the Harmonic Atmospheric Research Project - and the implications of tapping the Earth's magnetic field. As I mentioned, this is part of Moench's long-running rant against the government, so he looks at the positive and negative impacts of the experiment. The last time Moench sets up a page like this is in issue #543, page 3, in which Batman and Robin discuss the identity of "Faceless" and why he kills the way he does. These are not completely revolutionary ways of telling stories in comics, but it is something we rarely see, especially in a mainstream book, and Moench deserves credit for using the medium in this way. He has a lot of information he wants to get across, and trying different ways in the context of the book to do this makes this an even more fascinating run.

This is a great "unfinished" run in comics history, too. It's difficult to see how a run by a creative team that lasts 38 issues (with the primary team doing 33½ issues) can be considered "unfinished," especially when it includes stories with Black Mask, Killer Croc, Scarecrow, Mr. Freeze, Two-Face, Poison Ivy, Man-Bat, the Joker, the Penguin, and Clayface. It's obvious, though, that even though Moench didn't turn this run of Batman into a Marvel-like soap opera, he still had long-running stories that he wanted to get into. Early in the run he introduced Madolyn Corbett, a mysterious femme fatale who showed up a few times and then disappeared (and whose fate was decided in an issue of Shadow of the Bat, which I didn't read, so I don't know what happened to her).

Moench obviously wanted Bruce to have a love interest, so he created Vesper Fairchild, who had a great deal of potential that never materialized. The politics of Gotham City is also a theme throughout Moench's run, as the town gets a new mayor and Jim Gordon loses, then regains his job as commissioner. And of course, Moench's "master villain" never gets to show his stuff. In Moench and Jones' first issue, #515, we see a mysterious figure on page 9, panel 4. Batman is talking to Gordon at police headquarters, and Jones gives us an exterior shot of the building. On the street is a man holding a bat-puppet on strings. The first time you see him (and we don't see much detail about the face, but it's obvious it's a man) you might think nothing of it. You might even miss him altogether. However, he shows up again the next issue, on page 10, panel 3. This time he's standing outside of the morgue, wearing a top hat (which would become part of his "costume") and holding the bat-puppet with a noose around its neck. Early in the run, Moench threw him in a lot - he's in issues #518, #519, #524, and #529, the "Contagion" story, in which we see the puppet clearly as a skeleton wearing a Bat-costume - but then he disappears for a while. He shows up again in issue #540 and for the last time in issue #551, in which he is lurking near Bruce Wayne's car, indicating he might have some knowledge about Mr. Wayne that not a lot of people have. It also indicates that even though Moench and Jones (I'm not sure who came up with this character, although I'm guessing Moench did but Jones helped "design" him) knew that issue #552 was their last one, they either didn't care or believed they would return to the book. This is one of those intriguing characters in comics who never appeared again, and we're not even sure what Moench was trying to do with him. After issue #552, the Bat-editors decided to hit Gotham, a city in the northeast of the United States on no fault lines, with a major earthquake, which led to a few years during which the Bat-books were a mess, despite some decent stories. Moench and Jones moved on, and as far as I know, we have never found out what the two wanted to do with this mysterious puppeteer. After three years giving us some of the most bizarre and wonderful stories we have seen in mainstream comics in a long time, DC decided to return Batman to more of a standard hero kind of guy. That's not the worst thing you can get from Batman, but it's far less than what he had been for a few years.

It is a mark of DC's criminally insane policy of collecting series that none of these issues are in a trade paperback. That will probably never change, but the issues shouldn't be that hard to find nor too expensive. This is the kind of comic that looks like it will be too bizarre for the average superhero fan but because it's Batman, the fans of "cooler" books won't pick it up. That's unfortunate, because even though it stars one of the pillars of the DC Universe, it gets under your skin and takes you places most superhero books won't go. Jones' utterly unique vision of Batman and his world, along with Moench's twisted take on reality and what it means to have power and abuse it, make this a series of comic books that makes you think and makes you ponder and stays with you long after you have read them.

Here's a link to the archives! More comic goodness there!

[Edit: I know this post will make T.'s eyes bleed, but I hope he recovers nicely. We wouldn't want him suffering from "Kelley Jones Hate Disease" too long! I should also point out that last year's Moench/Jones mini-series, Batman: Unseen fits very nicely into this run. I'm fairly certain that's out in trade, so if you don't want to commit to buying all these issues, you can buy one trade and check out the synergy these two have. It's a blast of a series, although it's not quite as deep as this earlier run, but if you like it, you'll like these issues.]