I was going to call this "Comics are awesome," but I guess Bill Reed has already cornered the market on that title! Oh, and SPOILERS below, in case spoilering things bothers you. And some minor NSFW work stuff, too. Man, I'm out of control!

Anyway, with all the doom and gloom coming out of San Diego about the death of comics and how Artists' Alley is all depressing and shit and how the video games will soon come to life and eat all the creators and how even the movies and television crap isn't even tangentially related to comics anymore, it's useful to remember how incredibly awesome comics are. Hence, this post. Of course, I was already thinking about this before the con, but whatever.

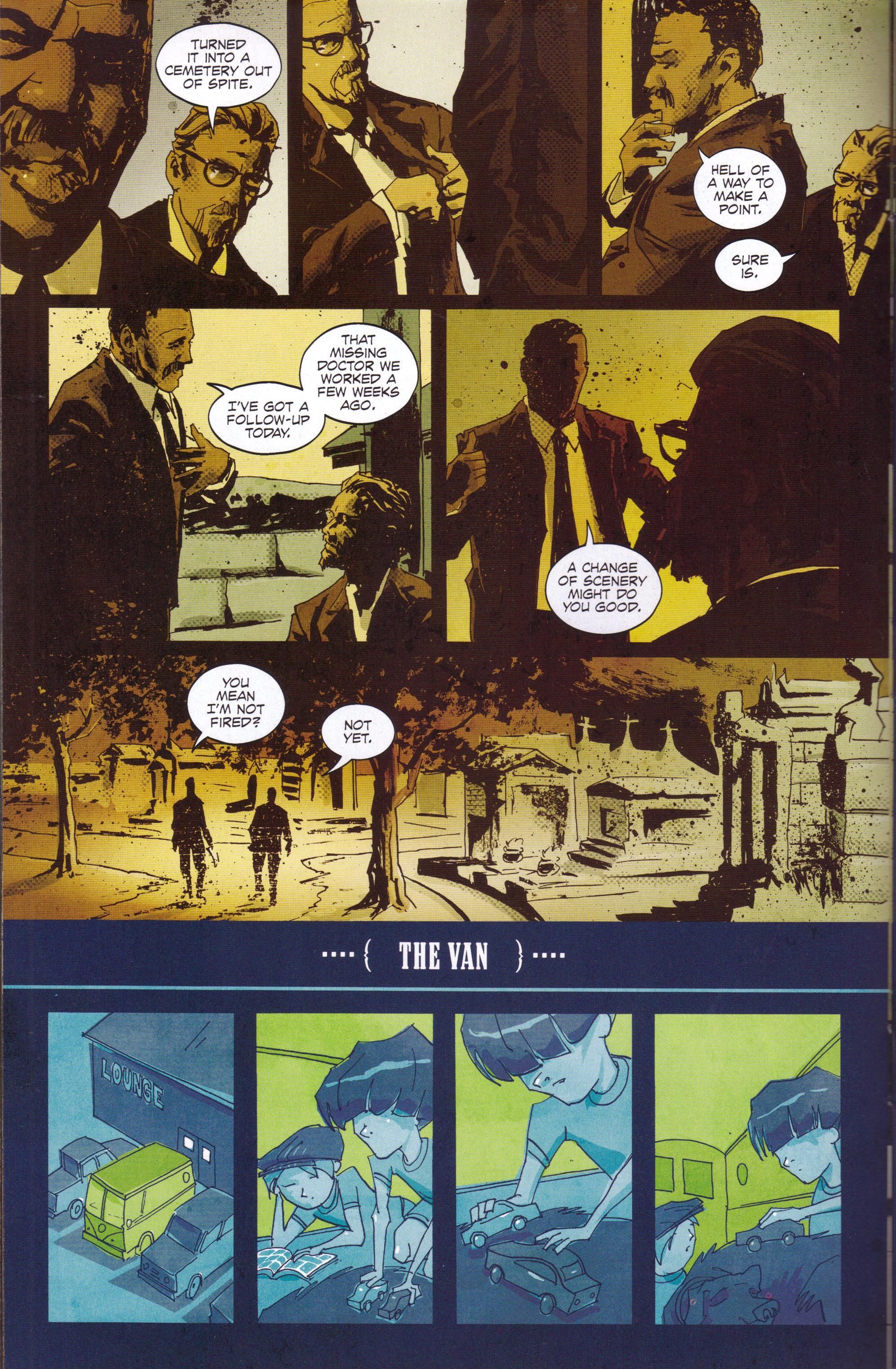

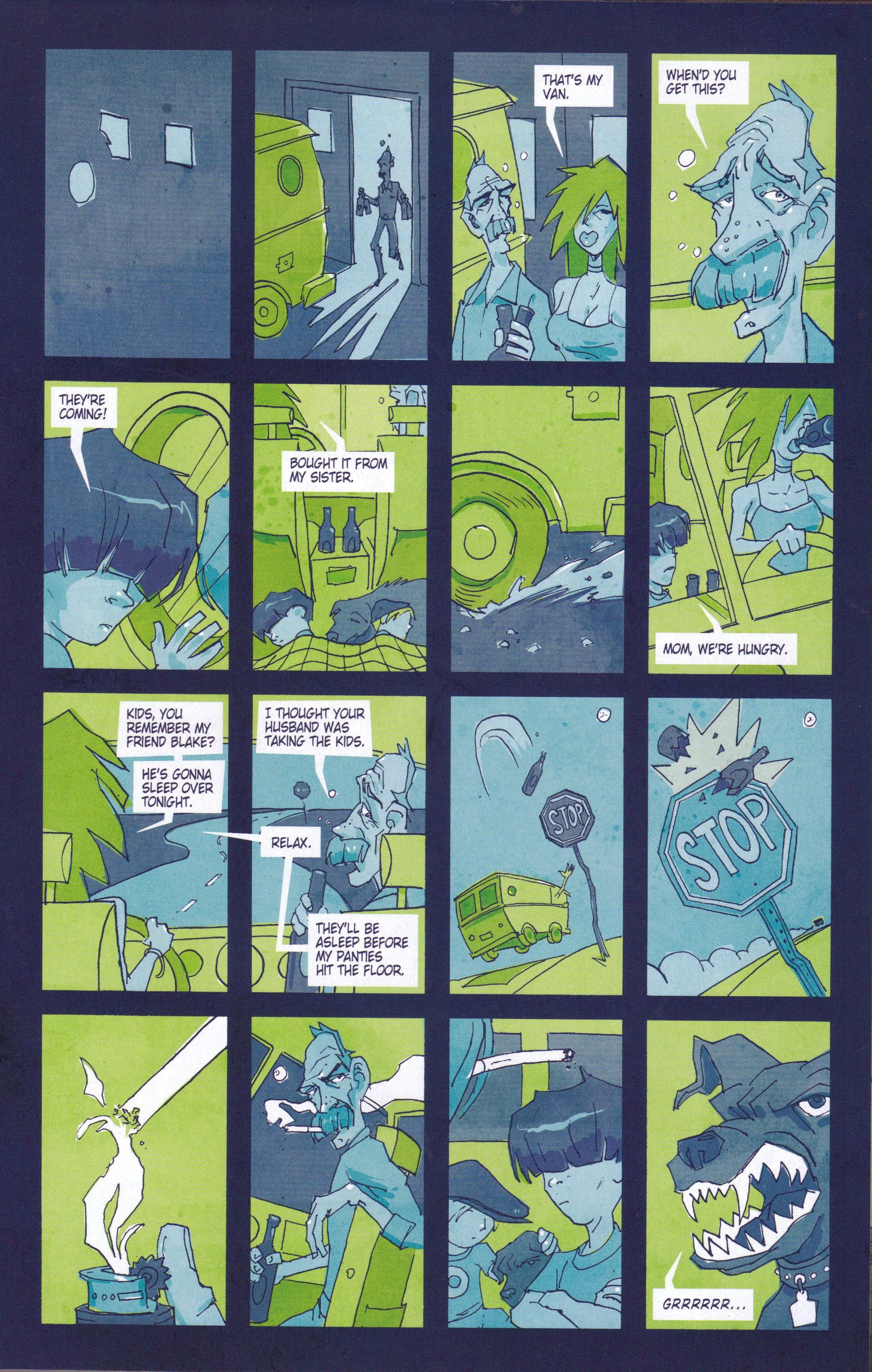

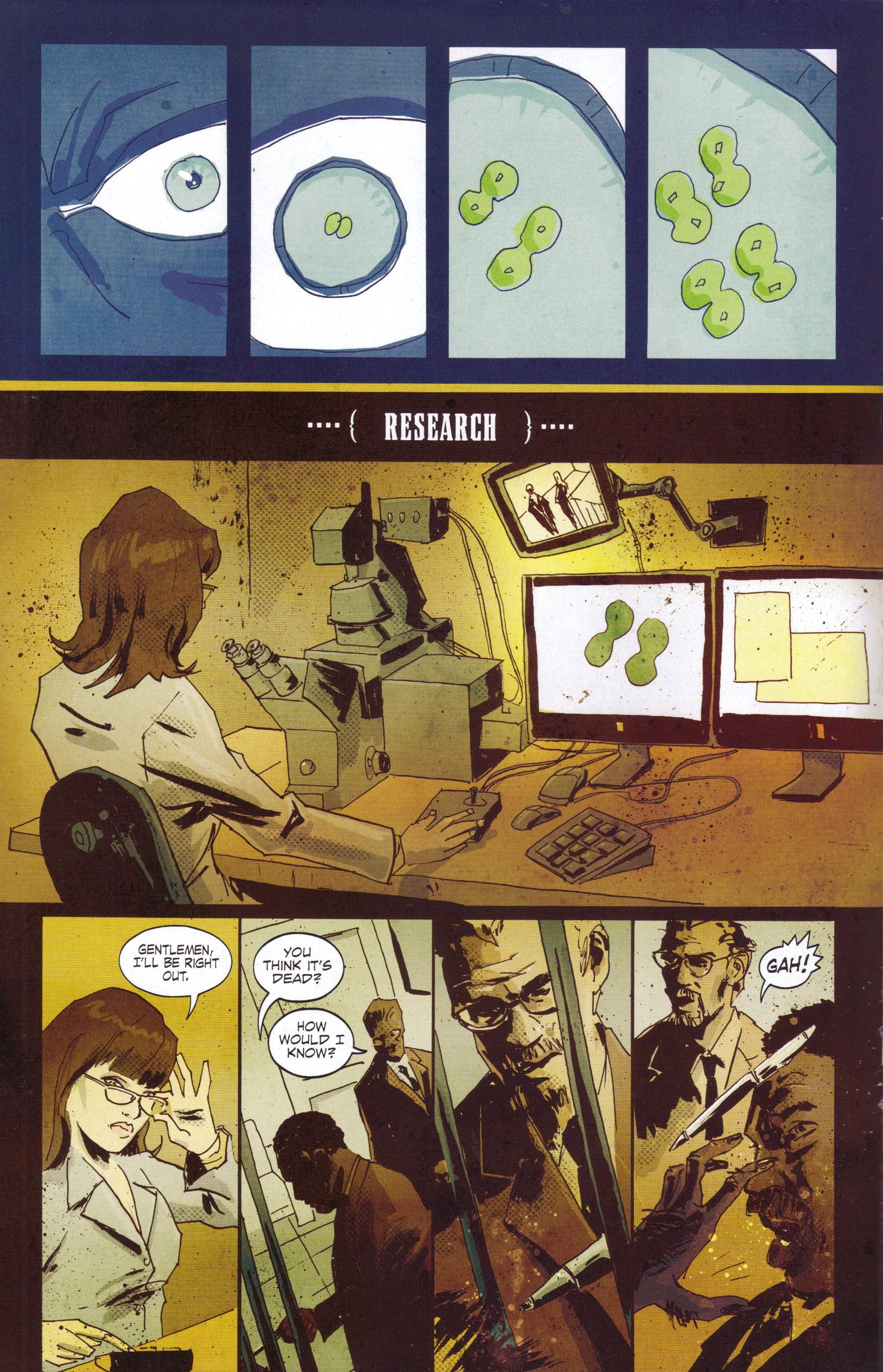

I was struck by the versatility of comics when I read an admittedly not terribly original comic, Sweets #1 by Kody Chamberlain. There's nothing wrong with Sweets, exactly, and I would encourage you to check it out, but Chamberlain traffics in very standard cop clichés to set up the story. According to Chamberlain ('cause I asked him), he did this to make readers feel comfortable before he pulls the rug out from under them in subsequent issues. Whether he will do that or not is not my concern right now. My point is that if you read a prose version of Sweets #1 or saw it as a movie, you wouldn't think much of it. You've seen it all before. But it's a good comic, because of what Chamberlain does with the art. Let's check out some pages:

These come right in the middle of the comic, and we have no context for them. Chamberlain doesn't explain them, and while we can certainly guess that it's a flashback to the main character's childhood, that's not a given at all. But it doesn't matter what they mean right now - if Chamberlain is any kind of storyteller, he'll let us know down the road. What's important is the way he conveys this information. The main story is presented in a fairly realistic fashion, as you can see. The coloring is heavily sepia-toned, true, but the locations and people are realistic. Then we get this hallucinatory interlude, where Chamberlain switches to garish blues and greens and a cartoonish drawing style that signifies a complete shift in location, time (perhaps), and even tone. The reason we can guess that this is a flashback is because we understand that this is a child-like way of presenting the information - the people are exaggerated, and even the panel where we see the van from the outside is a bit comical, with all four wheels off the ground as the man throws the beer bottle out. That it's a disturbing scene - the mother tells the man that her kids will be asleep before her panties hit the floor - makes the way Chamberlain presents it all the more odd and commands our attention even more.

Why is this impressive? Without being too obvious, this is something that can only happen in comics. In fact, we often talk (or write) about things that can only happen in comics, but usually we mean stuff that, visually, would take prose too long to describe and would cost too much to do in movies (or, now that CGI is cheap, look too cheesy). But rarely do we discuss the versatility of comics with regard to how an artist can control the tone of a book and the feeling it elicits within us simply by changing his or her style. Chamberlain's flashback couldn't happen the precise way in any other medium. The closest equivalent would be in movies, where cinematographers and directors change coloring all the time to indicate a different tone or time period. A filmmaker could easily take Chamberlain's sepia-toned "present" and introduce a lurid color palette for the flashbacks. It may or may not be as effective, but they could do it. But look at Chamberlain's characters. Unless a filmmaker animated them, there's no way human actors could look the way Chamberlain wants them to. His characters are filtered through a different perception. Movies have only one perception - the camera's. Which changes nothing about the humanity of the people involved.

That's not to say movies can't show us wacky creatures, of course. Science fiction, fantasy, and horror movies have done such things for decades. Very often those creations fit into the movie very well, even if they're not actually there (as in CGI creations) or if they're humans wearing masks or puppets. Human actors have become very good at interacting with things that don't exist or that they know are just other people dressed up. That's not my point, exactly. I'm talking about the way artists can change the way actual people look like to elicit a mood or a sensation, like Chamberlain does. It's very hard to do that in movies without it looking completely fake. Chamberlain's characters don't look "real," of course, but they're not meant to. If a filmmaker were to film Chamberlain's scene, either the people would look exactly like regular humans, in which case the impact of the scene wouldn't be as powerful, or the filmmaker would twist the way the people look to make them grotesque, in which case the scene would become unintentionally hilarious. Filmmakers can filter light and use odd camera angles to get an effect, but they can't change the essential "human-ness" of the actors. Comic artists can do this very well.

Chamberlain is, of course, not the only person who does this. That's why comics are so very versatile. There's very little that looks ridiculous in comics, whereas there's often quite a bit that looks ridiculous in movies. A great deal of CGI is thrown together cheaply and looks it, and even when the budget is gigantic, there's still something off about computer effects. The fact that it's hard to change the way people look often hurts more esoteric movies, as well. Something like Pan's Labyrinth relies on puppetry to achieve its distinctive and odd surreality, while The Cell, for instance, relies heavily on make-up and props. Both of these movies are artistic marvels (the debate on whether they're good movies is for another day), but the fact remains that in comics, it's easy to achieve these effects and it never looks too odd. Both Pan's Labyrinth and The Cell show a landscape that is different from our reality, so we accept their conventions. But comics are superb at showing "our" "reality" with a twist, mainly through the way the artist chooses to portray it.

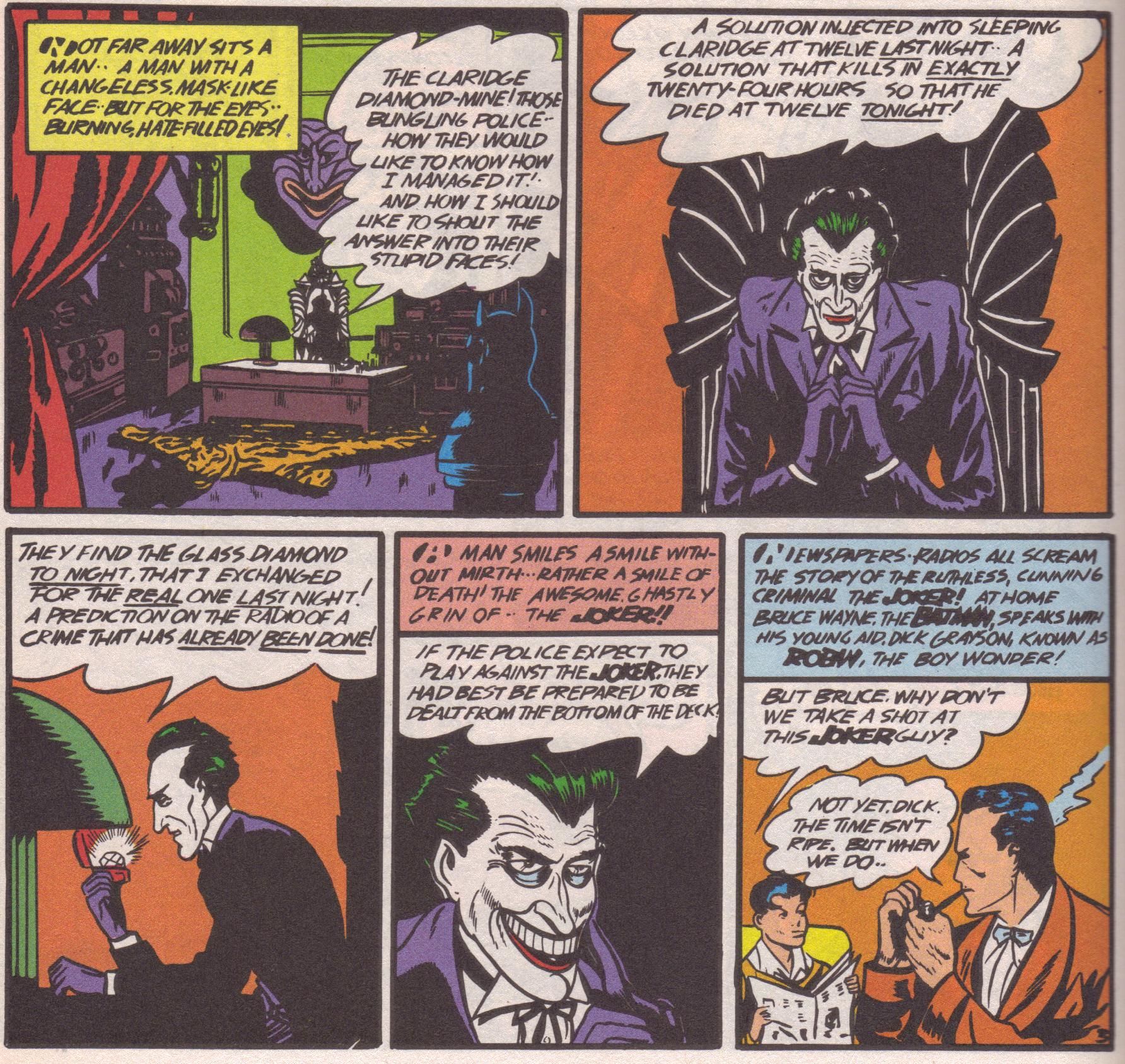

This isn't a new phenomenon, although it's become increasingly more obvious in recent years. The first appearance of the Joker is most effective in comics. Prose couldn't capture the visceral horror of seeing the rictus on Joker's face, while movies have never quite captured it either (Cesar Romero sported a mustache under his make-up; Jack Nicholson's frozen smile was creepy in all the wrong ways; Heath Ledger's greasepaint was a bit too "realistic"). But if we look at Batman #1, the first appearance of the Joker, we see this:

Whoever drew this (DC credits Bob Kane, but who the hell knows?) shows why comics are so effective. The Joker's smile isn't frozen in place, but his pallor and hair don't look too out of place in the world of Batman (considering that by this time, Bats had already fought vampires, Hugo Strange's monsters, and interacted with flowers with human faces). The Joker doesn't look ridiculous (as Romero and even Nicholson did) or unkempt (as Ledger did), he looks scary. And this is from 1940, remember.

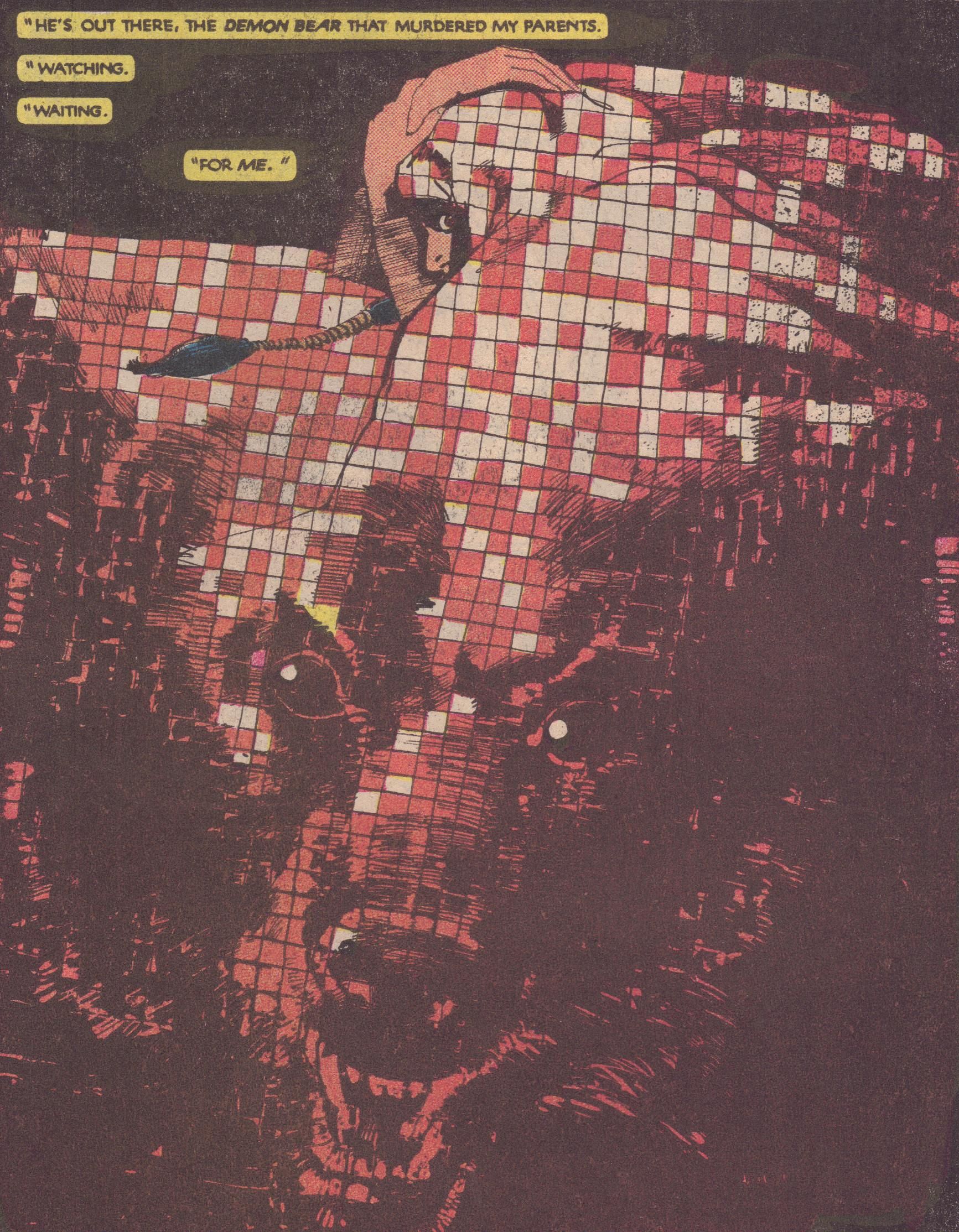

I'm not going to include all the examples from earlier in comics history, or even recent history, but there are many examples of this kind of thing. Bill Sienkiewicz is an early pioneer in the use of mixed media and surreality in comics, although he certainly wasn't the first (I'm not good enough a comics historian to know who is; perhaps Greg Hatcher or MarkAndrew can chime in). In one of the more famous first pages in comics history, he gives us this dramatic splash page in New Mutants #18, signalling a strange new direction for the book:

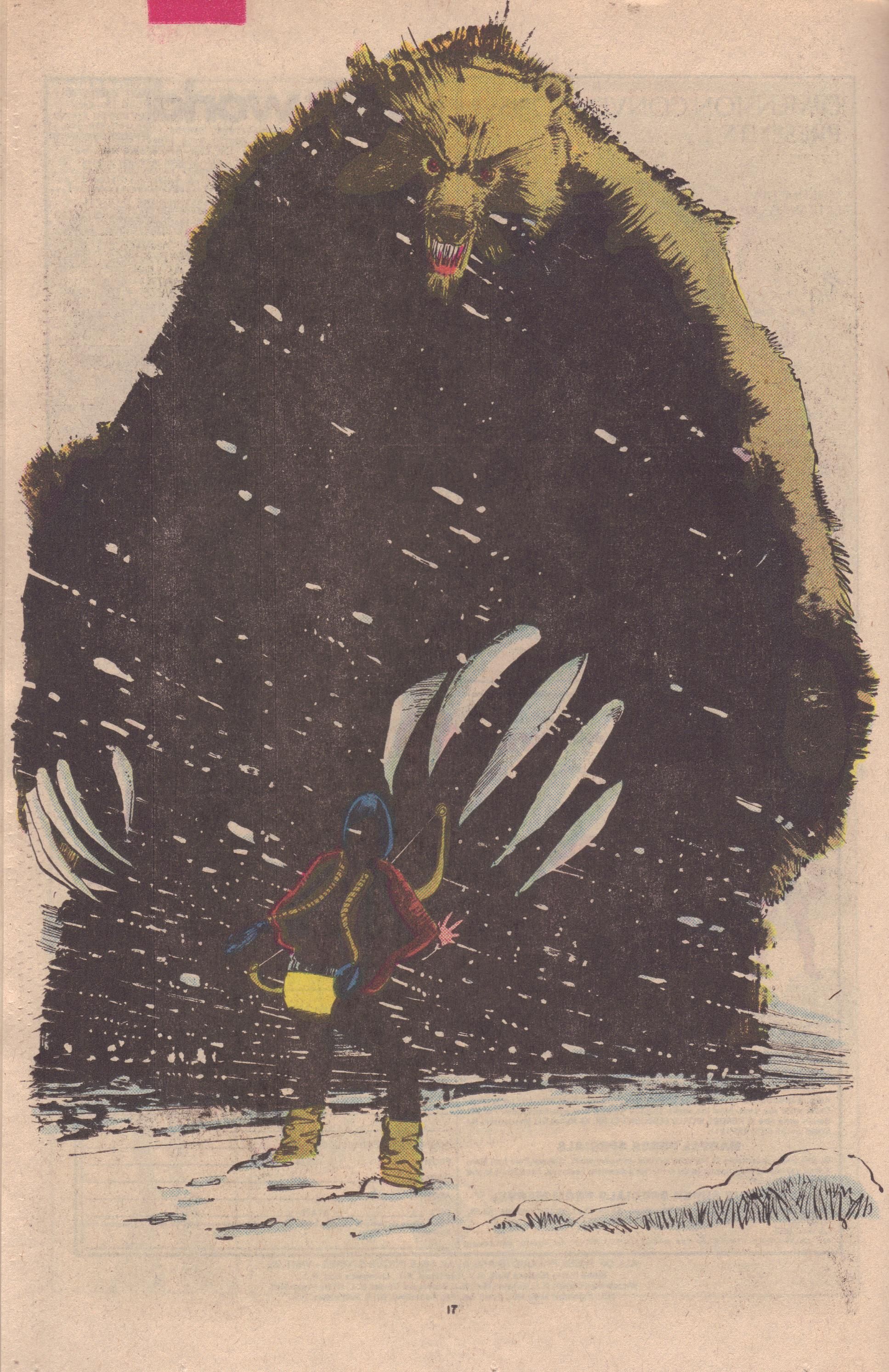

You can do that in movies, but it wouldn't look as organic as Sienkiewicz makes it here, with Dani's blanket slowly bleeding into the face of the bear. And, later in the issue, Sienkiewicz gives us Dani's first confrontation with the demon bear:

Again, a scene like this is possible in a movie, but not without CGI, to its detriment. The bear in the comic, as huge as it is, looks real, and because Dani is drawn in the same, Sienkiewiczian fashion, their battle feels more real than if a hot young actress was fighting against a green screen. Plus, the lack of background makes the bear and Dani pop more - a movie would have a background, even if it was snow-covered, and therefore the power of the confrontation would be muted a bit.

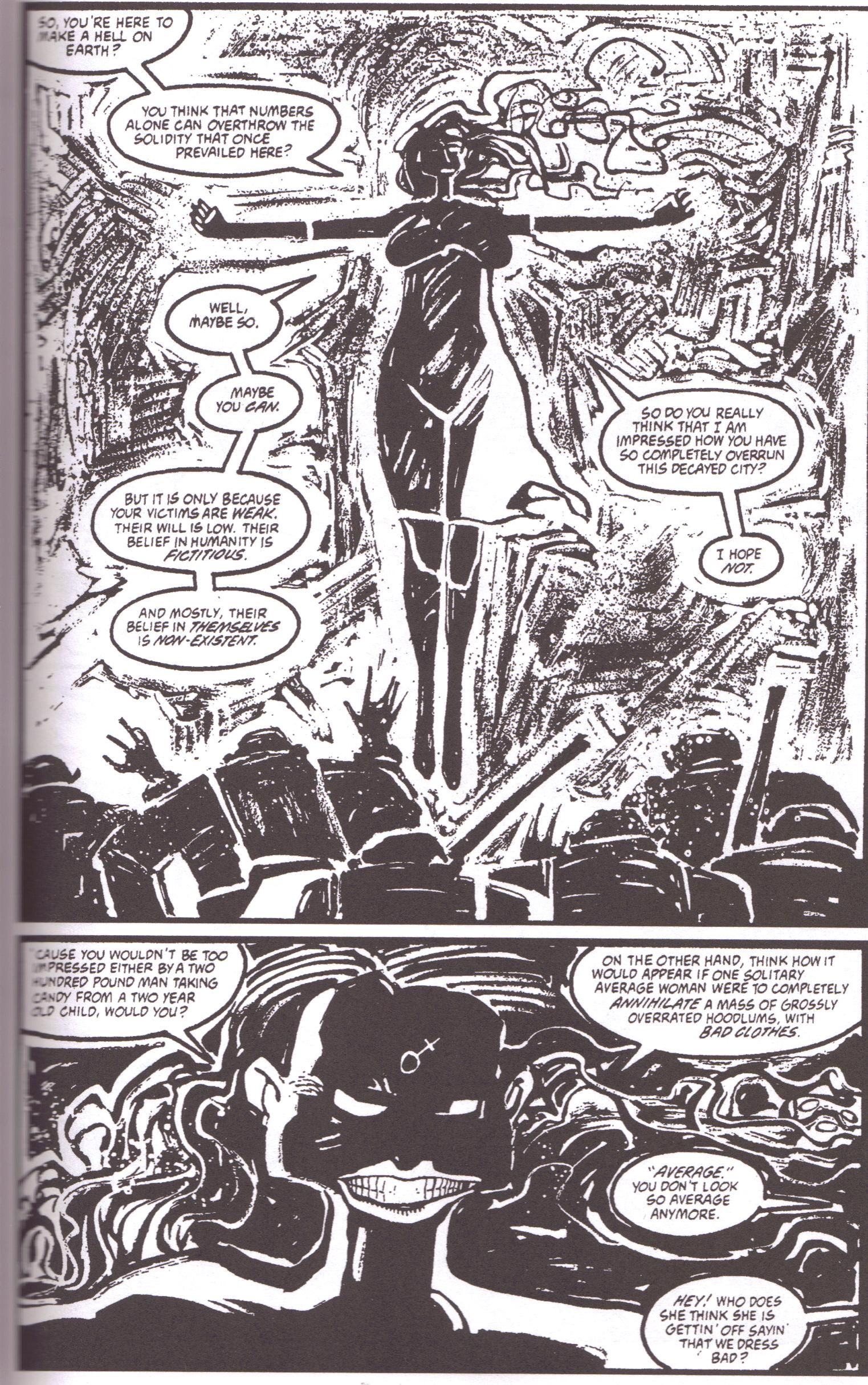

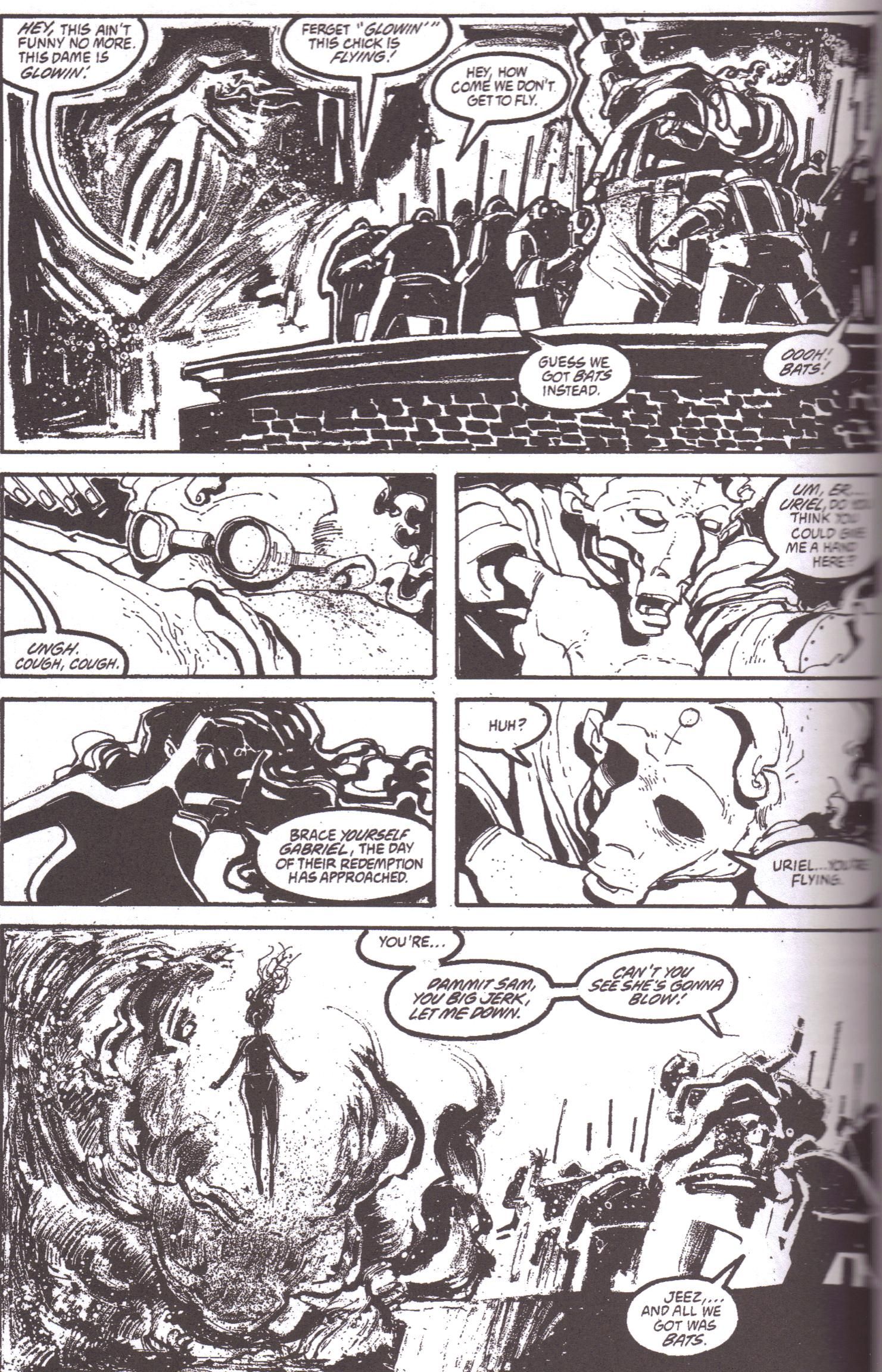

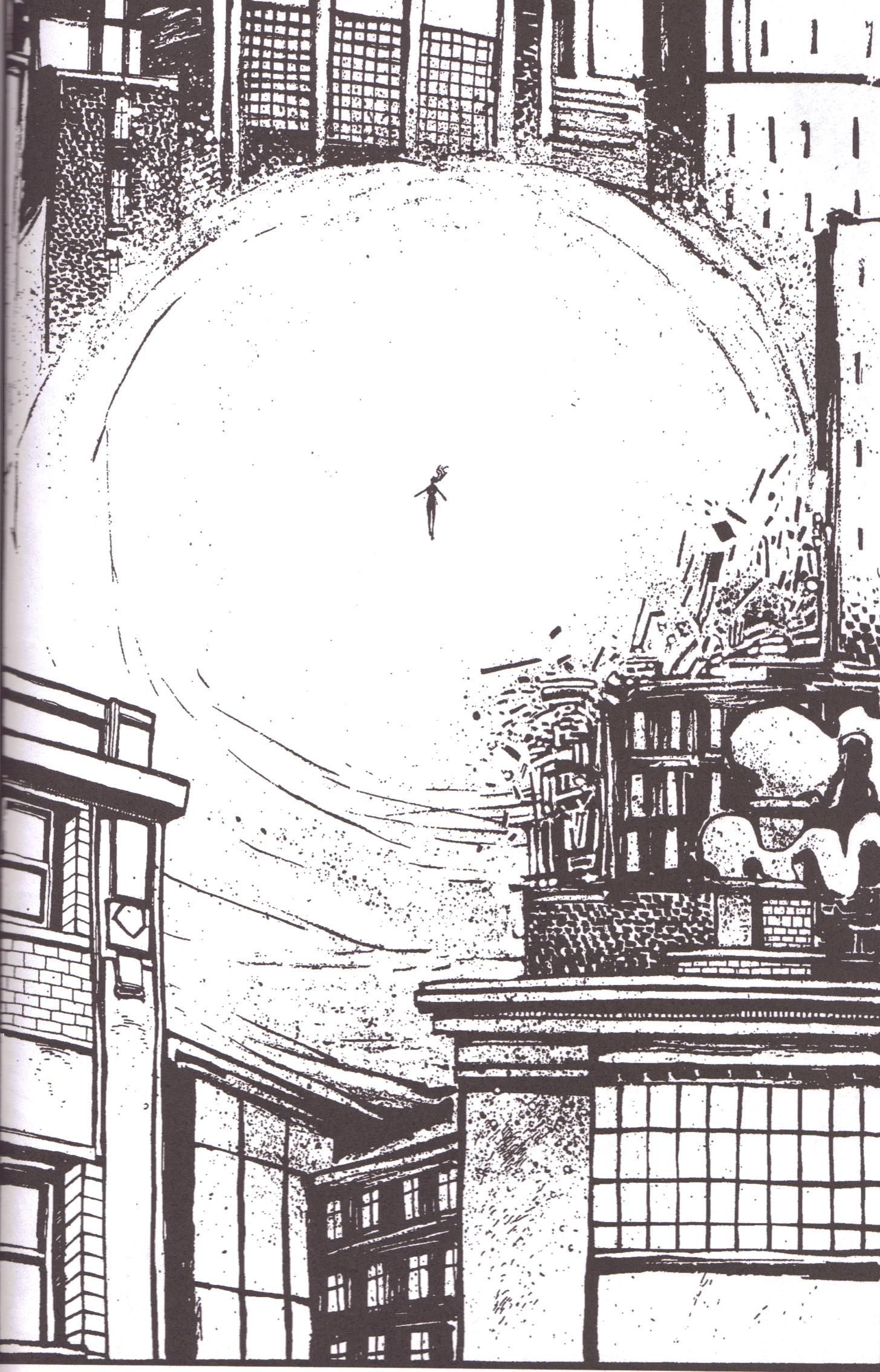

We can also consider Ted McKeever, who draws in a very non-traditional way. He certainly can draw attractive and "normal-looking" people, but his stock in trade is highlighting the grotesque in humanity and finding the beauty in that. Here's a sequence from Metropol that couldn't be done well in any other medium:

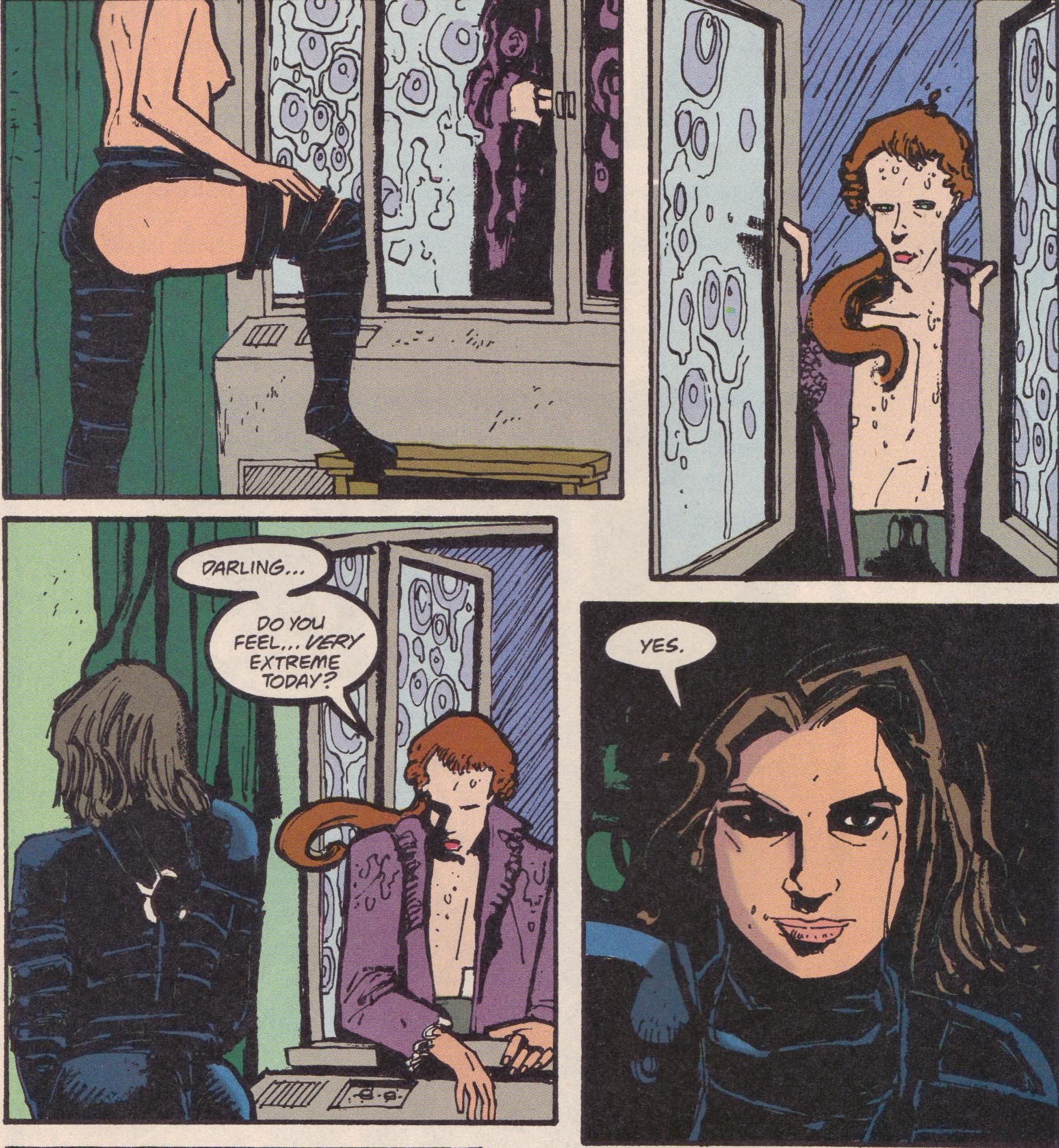

Yes, special effects could be used for some of this, but where would a filmmaker find an actress who is shaped like Uriel? The messy humanity that inhabits McKeever's comics is unique to him, and it gives his comics a wildly distinct look. And it makes the instances when he does smooth the edges out even more effective, as at the end of The Extremist:

Judy has been through hell and come out the other side, and although she has been portrayed raggedly throughout the series as she experiences all sorts of "extreme" behavior, in this moment, she's radiant. There's a twist, though, as Peter Milligan (who wrote the series) is, at that moment, showing us how lost and even sad she is. That McKeever chooses that moment to make her the most beautiful she's been throughout the series is fascinating. You might be able to pull this off in a movie, but it would be hard, because this moment is built on McKeever's rather twisted world view leading up to it.

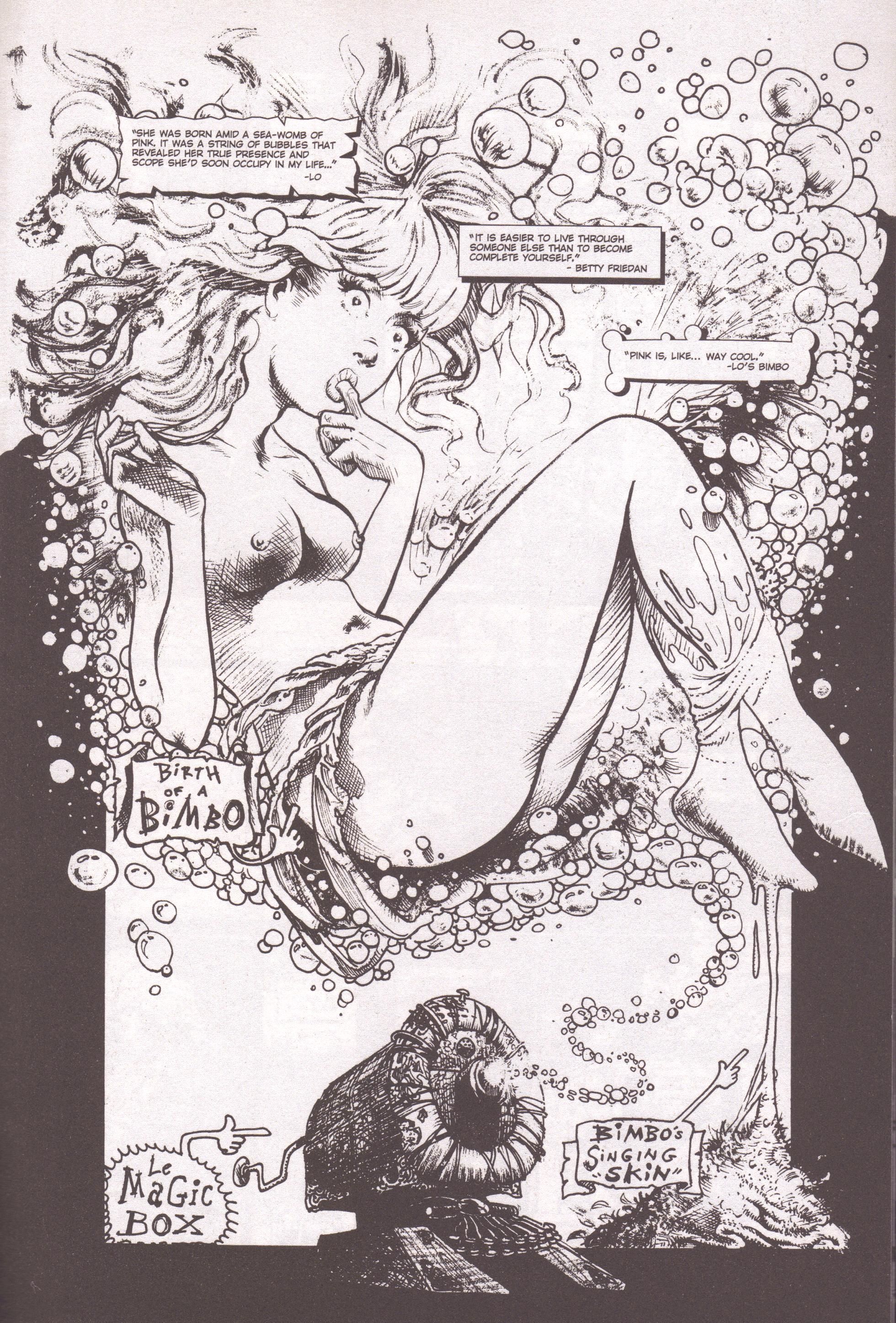

Sam Kieth is another artist who turns people and things into odd, surreal caricatures of themselves, all to add an extra layer of meaning to the work. Here's the first page of his very odd mini-series, My Inner Bimbo:

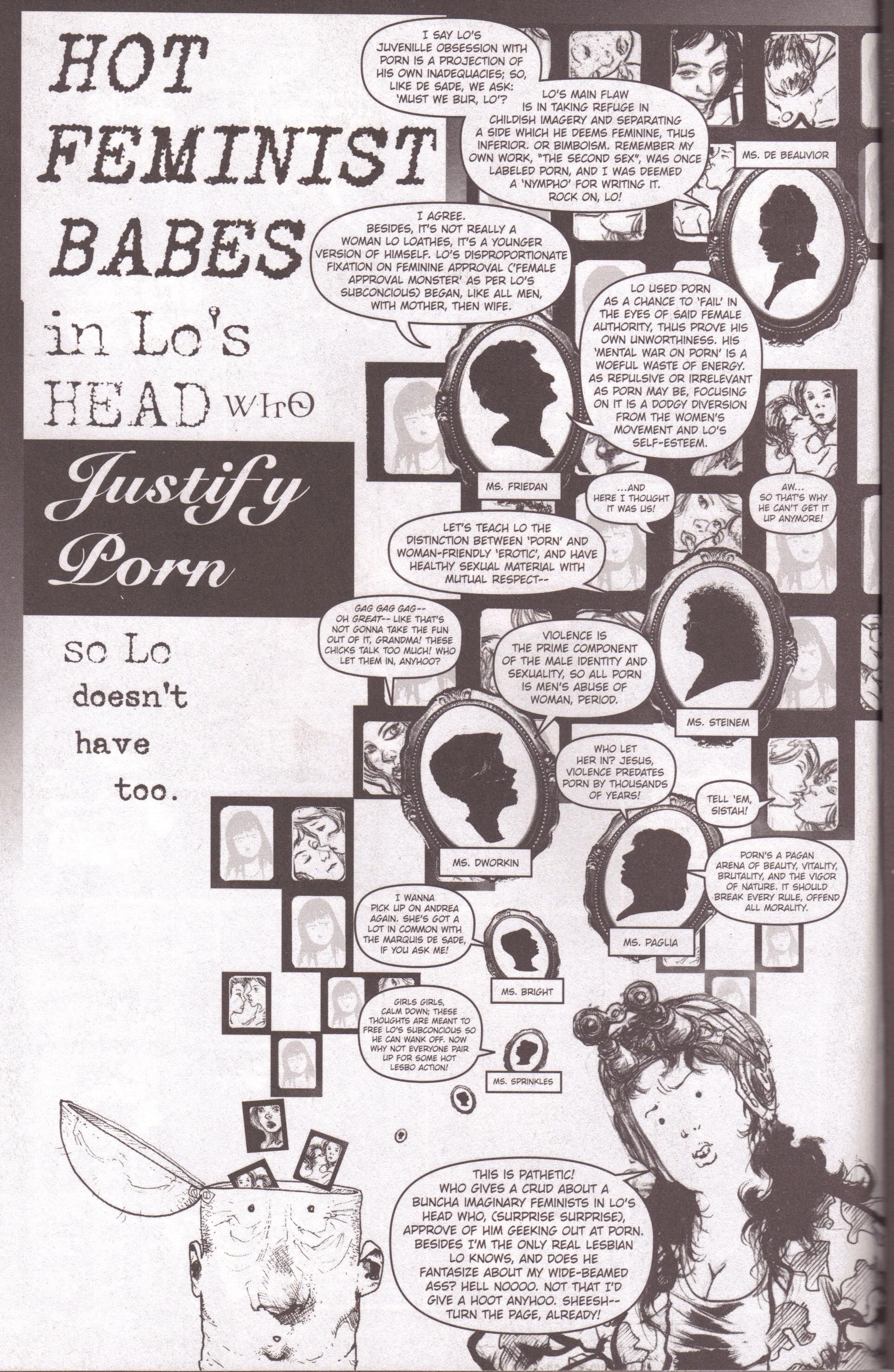

Kieth can certainly draw attractive women, as we see here, but he's also able to skew our perceptions slightly, as Lo's Bimbo is slightly rounder than you might see in a film (Christina Hendricks could play her, of course, but at 35 she's a bit old for the part, and young actresses wouldn't be caught dead with curves). The signs on the page look odd enough to fit, although they might not on film. The bubbles and the bimbo's "singing skin" would have to be added with CGI, and while the bubbles might look okay, the skin, which looks strangely erotic on this page, would probably look slimy and, frankly, gross if this were film. Here's a page from later on in the series:

Yes, this page is verbose (and it should be "to" instead of "too"), but the point is that Kieth opens Lo's head and all these silhouettes and cameos spill out, each spouting some kind of philosophical argument, and this page would be very difficult to transfer to any other medium. You could do a scene on film that would get the same general idea across, but Kieth packs this page with visual and textual information, and in a movie, it would have to be done so differently that much would be lost, including the wry humor of the banner proclaiming what the page is about. The fourth-wall breaking could be done, too, but once again, the woman on this page looks slightly askew, because she's drawn by a person with a unique style.

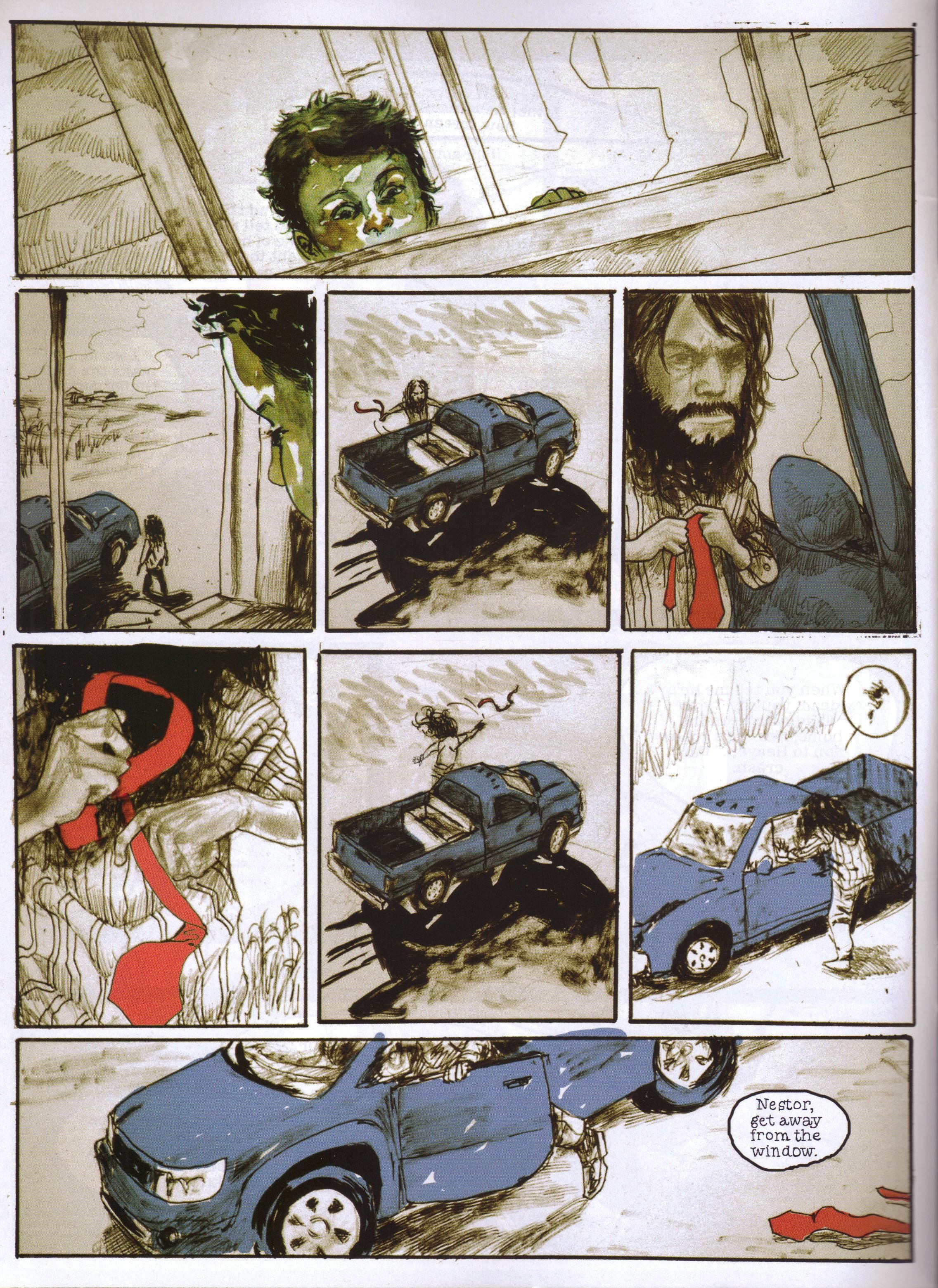

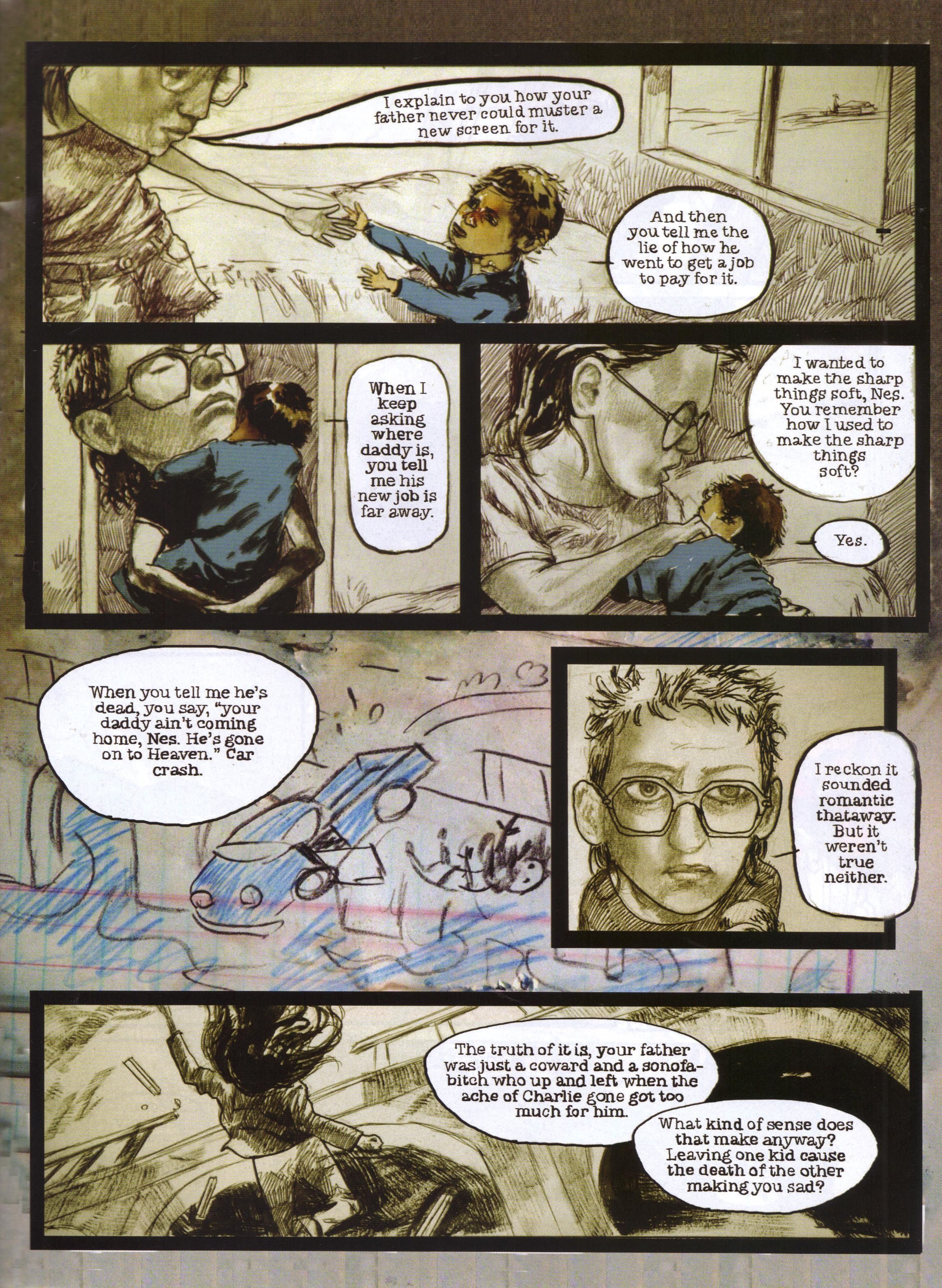

Even more recently, we have the stunning work of Josh Hagler on The Boy Who Made Silence, the best mini-series of 2008 and one of the most impressive comics of the past decade. Much of the effect of Hagler's work is due to the art (the writing is very good, but the art is magnificent) and through the way he creates moods with it. In issue #6, we get a flashback that is truly amazing in the way Hagler shows us how Nestor, the young boy of the title, views the world:

His parents' giant heads signify their dominance over the small boy, something movies would struggle to portray visually. It's been done, but much more garishly. We shouldn't forget Kari Marboe and Thomas Mauer's astonishing lettering when his father speaks to him, making his words more portentous and sinister only through the font and coloring of the speech balloons. The fact that this entire scene is presented upside-down is interesting, as well. Nestor is being baptized in a river and when he goes in, his perception of the world is skewed. Again, we've seen this in movies and even prose before, but comics do it more effectively.

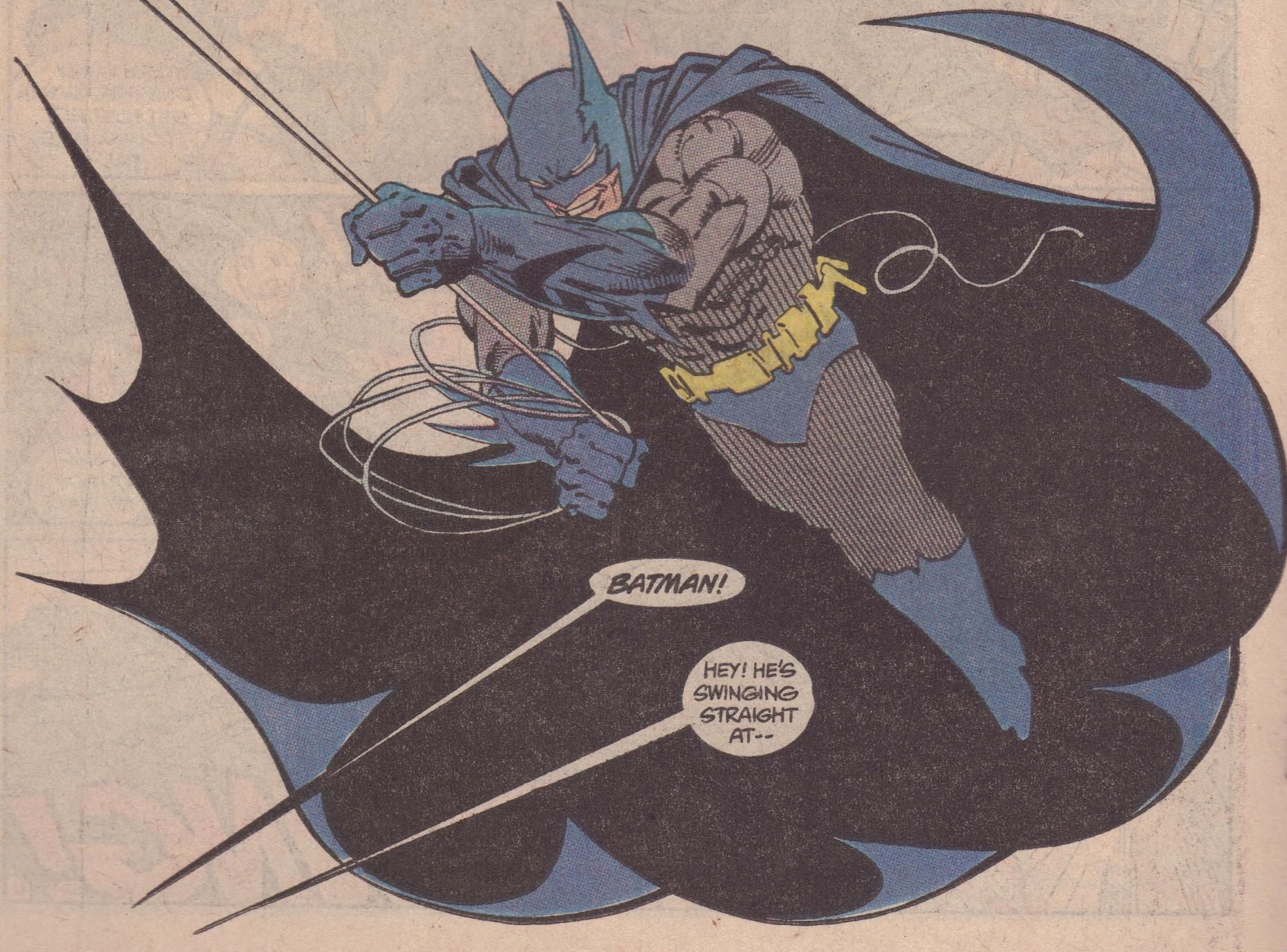

Even regular superhero books exhibit art forms that work better in comics than anywhere else, even now when special effects technology has allowed more versimilitude in big-budget men-in-tights films. Just one example is the cape, a staple of superheroes. It still looks a bit goofy in movies, even if it looks better than it did 50 years ago. But if we return to Batman, artists can go a bit nuts and it can still "fit" within their art styles. Todd McFarlane may have gone too far, but someone like Norm Breyfogle was able to strike a fairly good balance between a long, impractical cape and a good look within the context of the book:

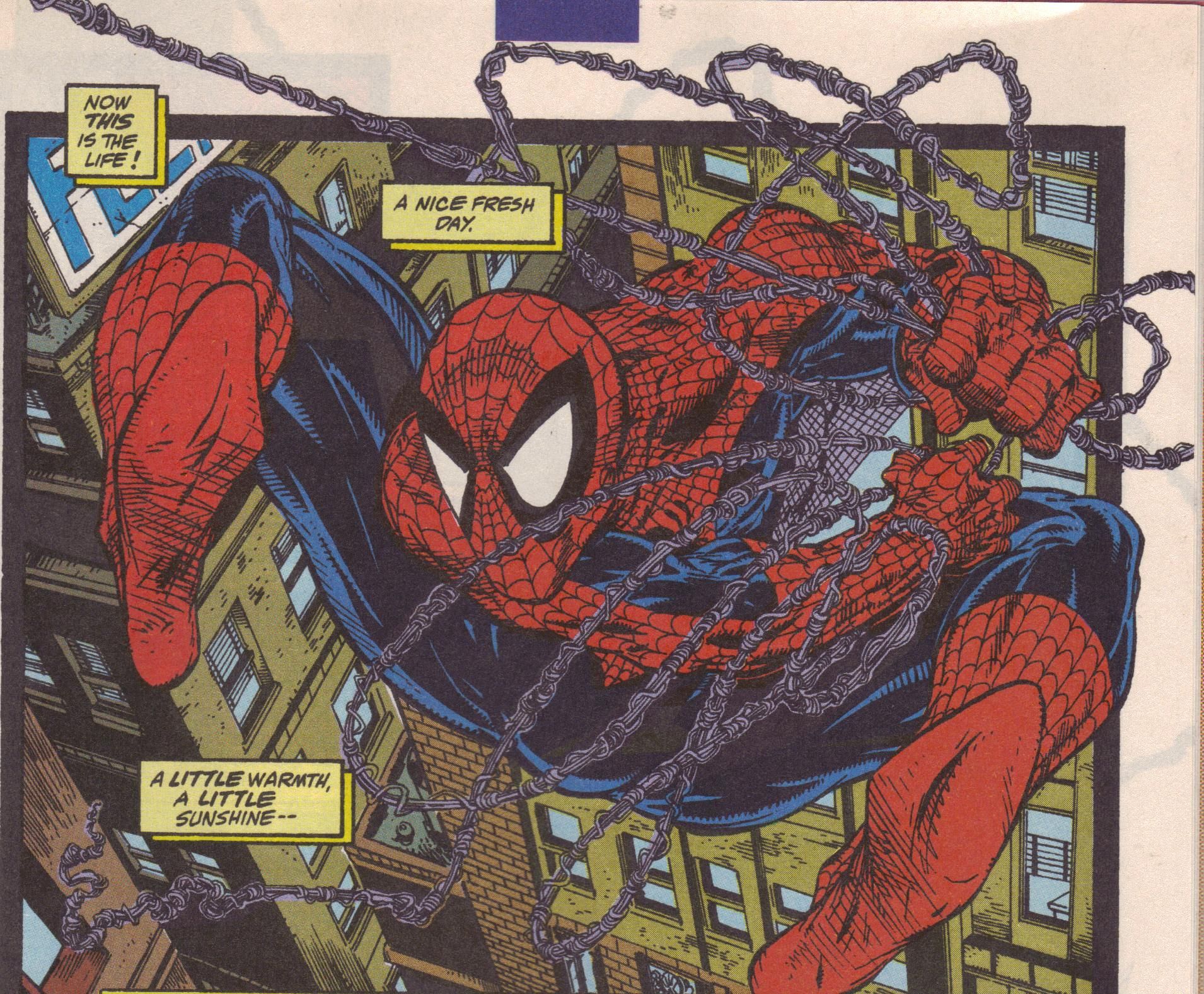

And just so as not to pick on McFarlane too much, his depiction of Spider-Man was quite revolutionary, as he made him far more arachnoid than ever before, something that, unless Sam Raimi had hired DJ Qualls to play Peter Parker (let's face it - now that I've thrown his name in the ring, you WISH he had played Spider-Man!), they couldn't have done in the movies:

The way art styles reflect "reality" in many different ways, changing the tone of the work based on how the artists draws people isn't the only way comics are more versatile than other media. Prose writers and directors, for instance, can create mysteries very well, even "fair-play" mysteries, but comics are, in many ways, superior to them. Comics can show images that need not be commented upon, just placed within the panel, and astute readers may pick up on them. In prose novels, clues must be mentioned or they don't exist, and this draws attention to them. Movies can drop clues into the frame, but the static nature of comics means that readers can go back over and over again to spot them - obviously, you can do this with movies, but it's a bit more difficult. Many comics don't take enough advantage of this dichotomy between words and pictures to present crucial information in a mystery - many comics mystery writers show clues and have the characters comment on them, which defeats the purpose somewhat, or they simply don't place clues throughout the book. But many writers do take advantage of the medium. Mike Barr is a good example, but perhaps the best murder mystery in American comics is, unsurprisingly, Watchmen. Here's the very first page:

There's not a ton of visual information on the page, but what is there is impressive. Moore and Gibbons give us clues to two of the main mysteries in the book - Rorschach's identity and the murderer's identity (note the truck by the sidewalk as Kovacs walks through the blood). They do this throughout the book, and only when you go back and look through it do you realize how airtight the plotting is and how intricate the clues are. Obviously, Moore and Gibbons are two of the best creators in comics, but this kind of storytelling isn't that hard. It's a shame that more creators don't do this sort of thing in their comics, because it's a wonderful place for it.

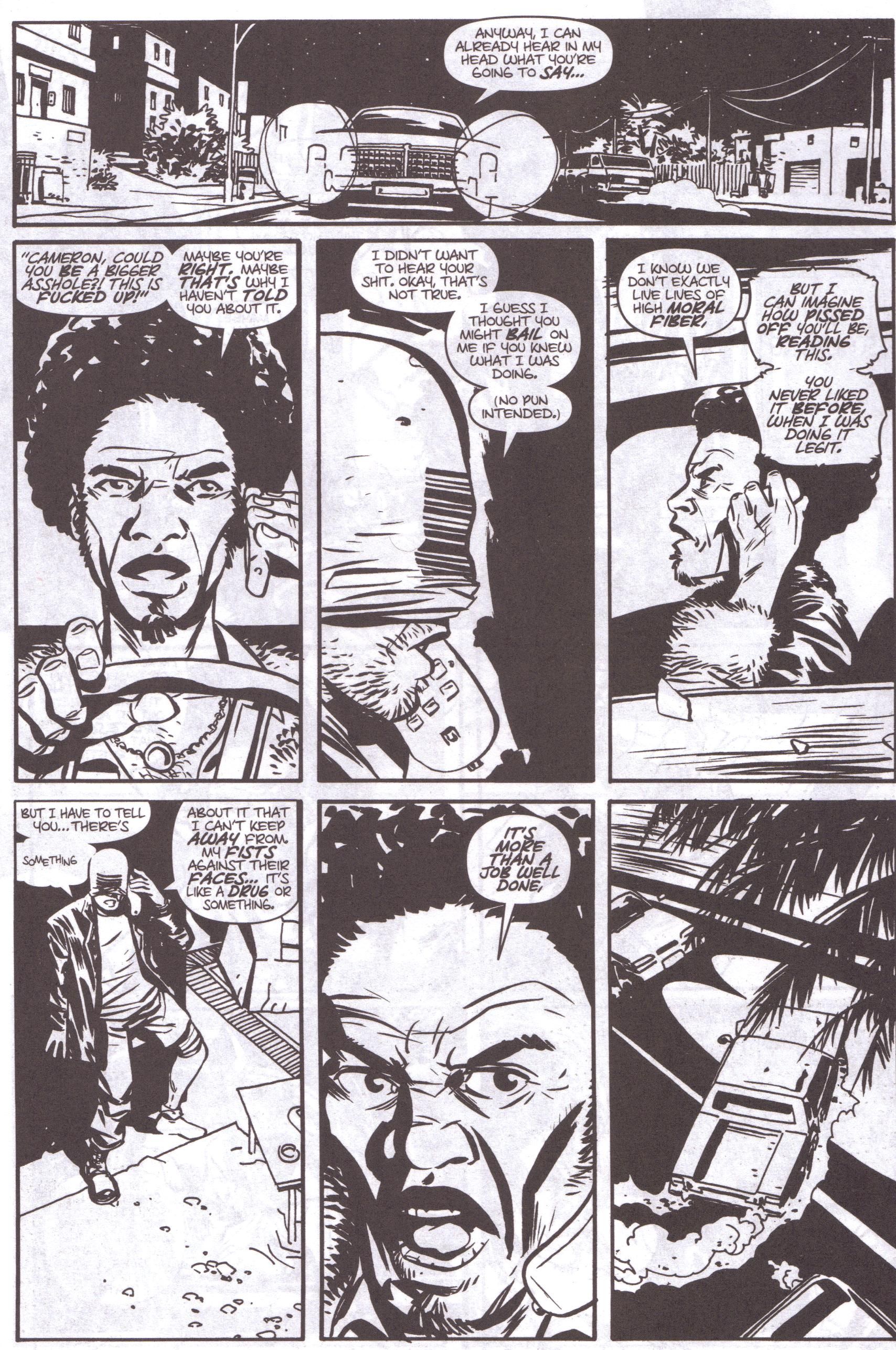

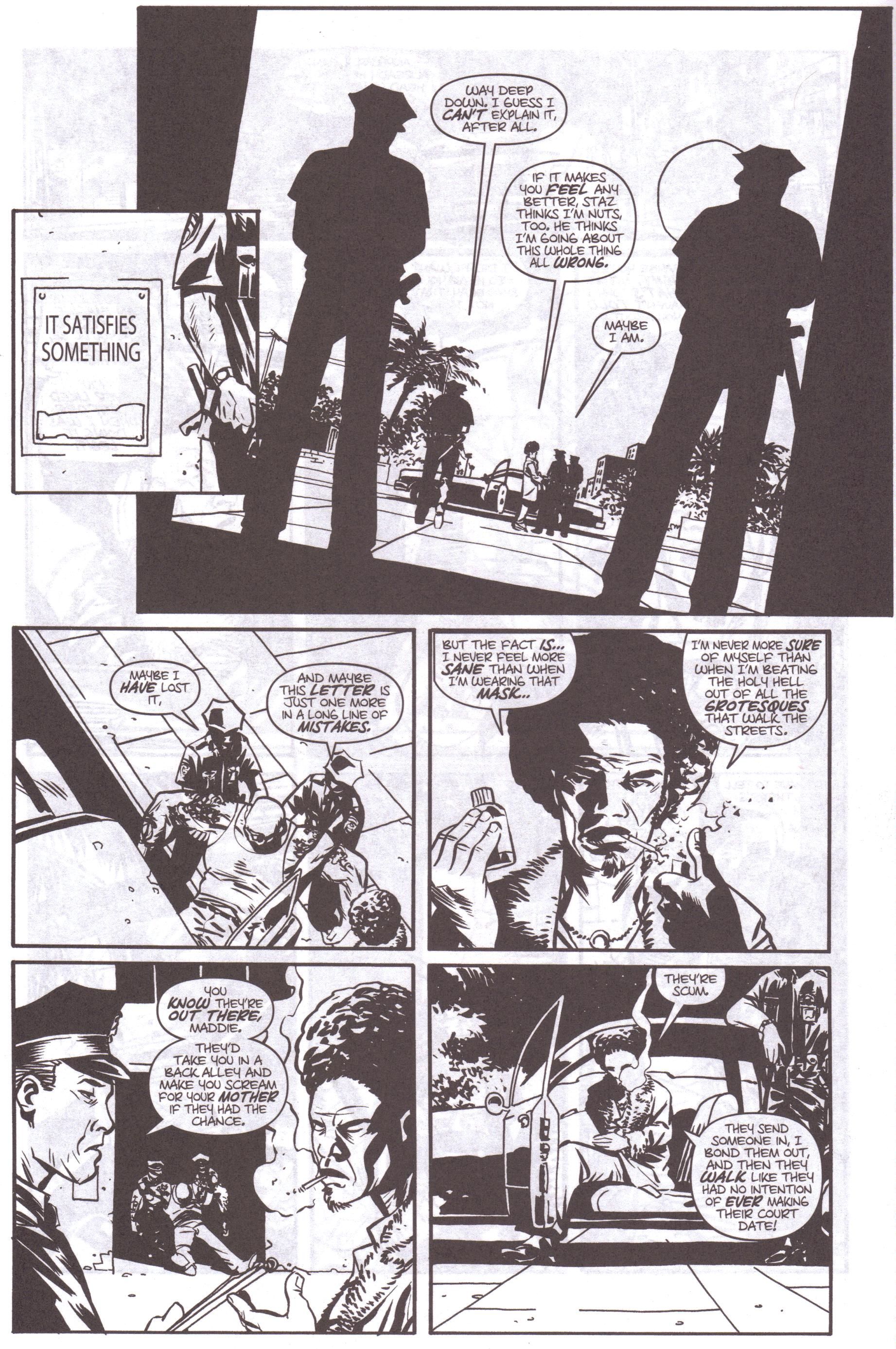

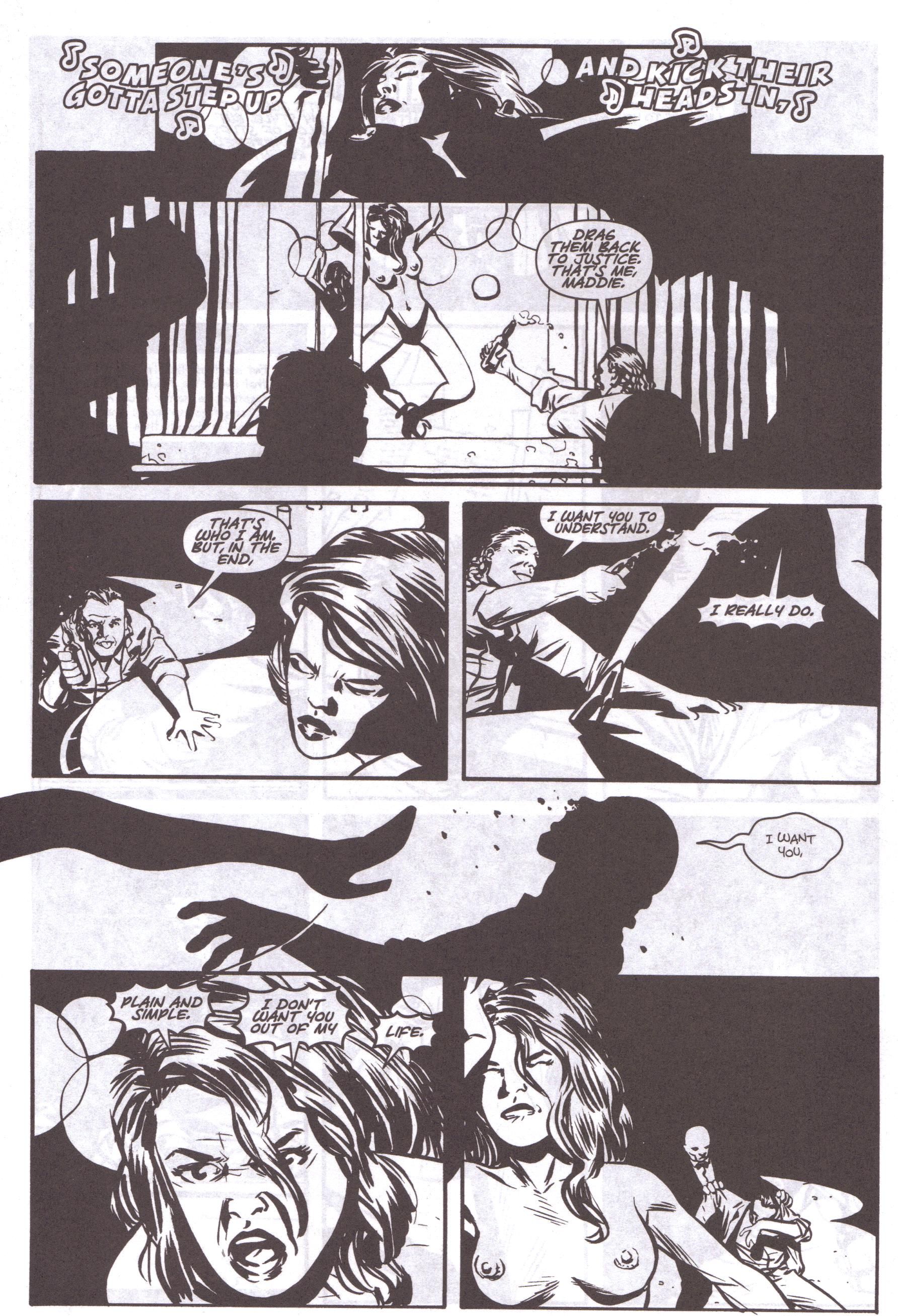

The juxtaposition of words and pictures has become more and more common over the years, reaching perhaps an apotheosis in the final issue of Joe Casey and Charlie Adlard's Codeflesh. This is the famous issue in which our hero, Cameron, writes a letter to his estranged girlfriend, Maddie, and Casey puts the text of the letter in word balloons and Adlard just draws scenes of the other characters going through their days, quoting Cameron's letter. It's an impressive achievement, made more so by the fact that Casey incorporates signs and music lyrics to tell the story, never missing a beat. And it's seamless. Check out three pages:

Movies have done things similar to this, but it would be very difficult to incorporate, for instance, song lyrics in a movie. This is just another place where comics are superior. (Chad Nevett wrote extensively about this issue five years ago, in case you're interested.)

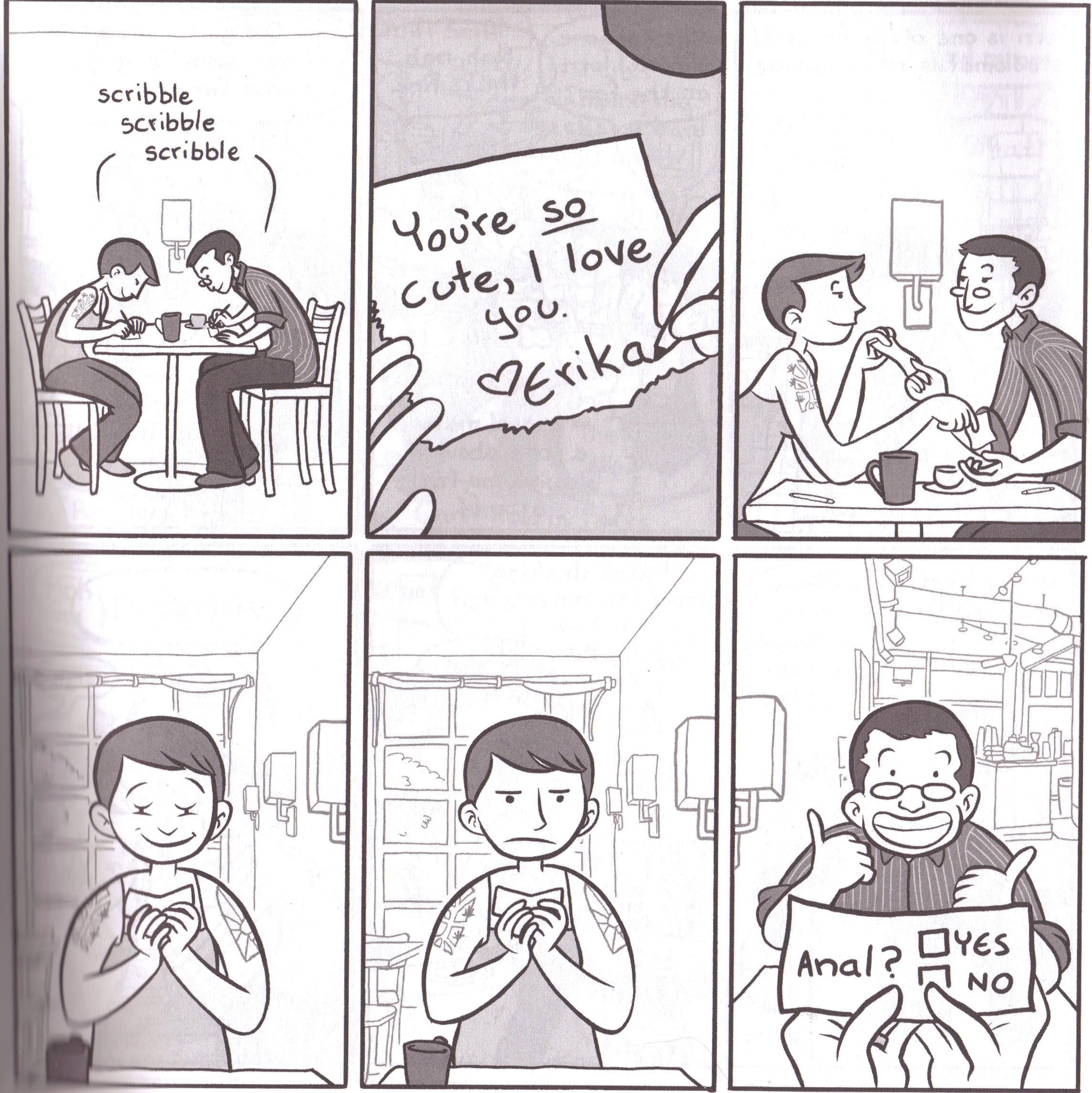

The last arena in which comics are more versatile than other media is humor. This might seem counter-intuitive, but bear with me. There are many examples of humor comics, but I was struck by this idea about humor while reading one of the books I bought in San Diego, Erika Moen's DAR! This is a fantastically filthy and very funny comic, and here's a sample gag:

Now, if we move past the fact that if you laughed at this, you'll love the rest of this book (and if you didn't, it's probably not for you), why does this joke work better in comics form than any other? In prose, the punchline would be funny, but we wouldn't have the simultaneous view of Matt's face (the guy's name is Matt, by the way), which heightens the humor. We could see this kind of thing in a movie, but what's fascinating about actors is that they often can't switch easily from smooth to goofy. Notice Matt when he's giving the paper to Erika - he's smug and satisfied with his paper. Then, when Erika gives him a withering look (and notice how easily Erika's face shifts from dewey and loving to disbelieving - we can even imagine her shaking her head disgustedly), he becomes a complete doofus. That's unusually difficult for actors to do. Seth Rogen or Jack Black could pull off the goofy look, but I doubt if they could look as suave as Matt does in panel 3, and that's part of the humor of the gag. Plus, the static nature of comics works in the joke's favor, as well - the shift in Erika's face between panel 4 and panel 5 is done instantaneously instead of in stages as it would if it were a movie, and that helps make the final panel even funnier. Many humor comics do this exceptionally well - beats in comics that stretch the humor out don't work quite as well in movies, although they do work. Comics just do it better.

I'm not bashing movies, of course, because film does some things much better than other media. There's something wonderful in watching an actor inhabit a role and create a character, changing the way we perceive the movie just by making certain choices in facial movements and vocal tone. Much like great comic art can occasionally elevate a pedestrian script, a great actor can make a mediocre movie script worth seeing. An actor can change the timber and volume of his or her voice to add greater gravitas to what they're saying, something comics (obviously) can't do. One reason why I don't like "casting" actors in comic books is because you only get the facial recognition, which is often the least interesting thing about an actor. Plus, music in a movie can't be underestimated and can be used to great effect. Movies do many things very well. Comics, however, do more things better, and the things they lose can be overcome with those things.

I realize I'm preaching to the choir here (which is why I should write about comics for Time or Newsweek, man!), but too many comics readers become flabbergasted when outsiders dismiss the art form as "men in tights" and can't refute them except by saying, "Well, it's much more mature than that - look, they're killing babies now!" Comic art can take the experimentation of fine art and wed it to the storytelling nature of movies, creating something unique and wonderful. Comics' static nature might seem to weaken it when compared to movies, and its visual nature might seem to weaken it when compared to prose's ability to describe turbulent emotions or wondrous landscapes, but good artists can make those perceived weaknesses and make them work beautifully. Whenever I read something about comics written by non-comics readers (even in something like Entertainment Weekly, which covers more comics than most periodicals), there's a tendency to appreciate the "realism" of a Greg Land or Bryan Hitch, whose work makes comics almost indistinguishable from movies except that they, you know, don't move. I understand that movies are where the money is, so many comics creators are making their comics hew as close to movie pitches as they can, but I would argue that ultimately, people like Mark Millar or Hitch are embarrassed to be comics creators - they want to be in the movie business and see comics as a stepping stone to that. Embracing the form means trying to continue in a grand tradition of telling stories with static pictures and using the uniqueness of the medium to make comics that wouldn't fit easily into the film medium. I always think of books I love that are, essentially, unfilmable. Did Mark Danielewski care about making House of Leaves accessible to movie makers when he sat down to write it? It's a terrifying book, to start, but Danielewski experiments with the way to present prose, and that makes it a work of genius (I haven't read Only Revolutions yet, but it's also an extremely experimental book). One of my favorite authors, Milorad Pavić (who died last October, unfortunately), wrote wildly entertaining and experimental books. His best, Dictionary of the Khazars, is laid out like, well, a dictionary, and tells all sorts of stories, both modern and set during the heyday of the Khazars (circa AD 700-800). He also wrote Landscape Painted With Tea, which takes the form of a crossword puzzle, and Lost Love in Constantinople, for which readers can use the tarot to determine in which order the chapters can be read. Another favorite author of mine, Italo Calvino, challenged readers through his fiction as well (his best book, If on a winter's night a traveler, is one of the few extended second-person narratives I can stand). Writers in comics rarely challenge readers in this way (not to say they don't ever, but not as often), but the great thing about comics is that artists challenge their readers all the time, and it often goes largely unnoticed because the art doesn't "fit" with what most fans think of as "superhero" art. There's certainly a place for Bryan Hitch in comics (and I usually like Hitch's work), but it's unfortunate that it's the standard. Comics offer so much more, and the best comic art, like those books I mentioned above, is almost impossible to transfer to another medium.

So next time your friends pooh-pooh your comic book reading, pull something out a little more challenging than the latest issue of Avengers or Justice League. Comics are infinitely versatile, more so than movies, certainly, and maybe more so than prose. That's why, even if I get burned out on comics every once in a while, I always find something new to dazzle me. And that's why I keep reading them!