Comics College is a monthly feature where we provide an introductory guide to some of the comics medium’s most important auteurs and offer our best educated suggestions on how to become familiar with their body of work.

This month we'll be taking a tour through the short but incredibly powerful and significant bibliography of artist Pheobe Gloeckner.

Why she's important

Before I sing Gloeckner's praises a bit of a confession is in order. When I first conceived of Comics College, the idea was to pick creators that would have a large enough body of work -- but not too large -- currently in print to allow me to organize their bibliography in ways that would be helpful to the newcomer: Read this, don't read that, etc. I knew that putting in all these "categories" as it were would mean I wouldn't be able to include certain cartoonists known mainly for one body of work -- comic strip artists like Frank King and Chester Gould, for example -- but I figured it was still vague enough to be inclusive.

I quickly found myself with a problem, namely that a number of important female cartoonists -- Alison Bechdel, Carol Tyler, etc. -- had rather slim bibliographies. It seems silly on retrospect, but I liked that the individual Comics College posts had a certain bit of length to them. It gave them the illusion of depth, I thought. And it seemed odd to me to recommend works by an artist, regardless of how deserving they might be, when said artist only had two or three books under their byline.

But if any cartoonist deserves to buck this admittedly stupid notion it's Gloeckner. She may not be the most influential artist to come out of Weirdo/Twisted Sisters/post-underground scene, but she's easily one of the finest. Her comics aren't for the faint of heart, however. Last month we talked about Jacques Tardi, an artist who pulls no punches when it comes to depicting the violence of the external world, especially on the battlefield. Gloeckner is the same, but her battlefield is internal and personal, one of abuse within the family rather than in society. It's a world where childish naiveté and budding sexuality are tramped on and taken advantage of by adults and peers, and where various parental figures are horribly complicit in one form or another.

Gloeckner refuses to shy away from uncomfortable issues or visceral images. Those who might feel uncomfortable at the sight of an erect penis, let alone an anatomic, medical cutaway image of a young woman performing fellatio on said penis, might have qualms about delving into this work well before they come to the really upsetting stuff. But Gloeckner is not some mere shock jockey, throwing explicit images and topics at the reader just to get a reaction. Combining cartoonish exaggeration with a love for photorealism and craft that speaks to her background as a medical artist, her comics hit a raw, emotional nerve in a manner unlike any other cartoonist around and show a sympathy and understanding for the subject matter and characters that belie any suggestions of simplistic prurience.

Where to start

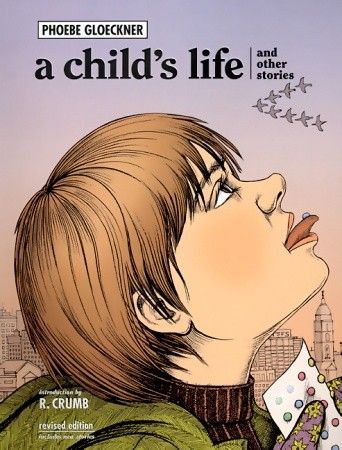

The ideal place to begin is with A Child's Life, which collects the short stories she did for various comics anthologies in the late 70s to early 1990s. Most of these stories concern Gloeckner's alter ego, Minnie Goetz and the verbal and psychological abuse she suffers from her monster of a stepfather, and later, from her mother's boyfriend, with whom she has an affair. The comics here have an odd, otherworldly effect, where inner fantasies and slightly off-kilter proportions hint at the trauma and potentially irreparable harm being done.

If nothing else, one should get this book to read "Minnie's Third Love." Largely regarded as one of the best comics ever made, let along Gloeckner's best work, the story is a harrowing and unforgettable journey through drugs, prostitution, sexual abuse and more, as poor Minnie falls for Tabitha, a strikingly good looking junkie who is perfectly happy to sell Minnie to "friends" in exchange for drugs. It's quite unlike any comic you'll ever read partially because it isn't devoid of humor and refuses to deal in obvious, simplistic moralizing but instead takes pleasure at being able to not only survive such horrors but exorcise them on paper.

From there you should read

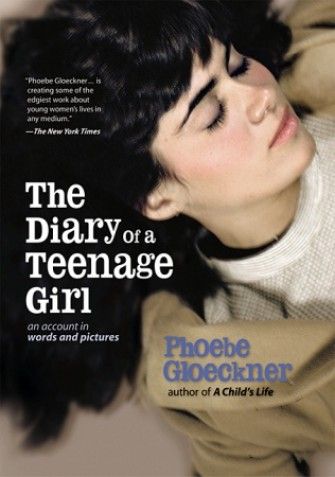

Gloeckner returned to Minnie's travails in Diary of a Teenage Girl a novel that combines straight prose with comics and illustrations. As the title suggests, the book consists mostly of excerpts from Minnie's diary, with the comics segments providing extra context. The plot focuses on Minnie's affair with Monroe, her mother's middle-aged boyfriend. While perhaps not as graphic or shocking as some of the material in A Child's Life (though Gloeckner certainly doesn't pull any punches), Diary is no less heartbreaking or evocative a work of art. Minnie's desperate desire to obtain love and acceptance, her insecurity and lack of self-worth, and her intelligence come through beautifully. Any book that attempts to put you in the head of a teen-ager is tricky -- one wrong word or false moment and the whole thing comes crashing down -- but Gloeckner is able to make Minnie and her mid-70s San Franciscan world come alive with seeming aplomb.

Further reading

Gloeckner's latest work, La Tristeza, concerns the murder of a young woman in Ciudad Juarez, a small Mexican town near the U.S. border -- a town where an alarming number of young women have disappeared or been murdered. Abandoning pen and ink, she instead seems to be combining photography, what I assume to be hand-crafted models and Photoshop (or some other type of imaging software) to create what appear at first glance to be little tragedy-filled dioramas. As you might expect, the work offers an ugly -- and at times bloody -- look at humanity, but Gloeckner's artistry shines through nevertheless. Gloeckner has been working on this project for awhile, and judging by her last blog post, the darkness of the story seems to be taking a toll on her. Hopefully she'll manage to pull through and finish it sometime soon. Very little of this work has been published yet, but you can read a small but significant sample in I Live Here, a the Mia Kirshner-edited anthology of stories and comics about refugees and people living in volatile or otherwise troubled areas of the world.

Ancillary material

A few of Gloeckner's most recent comics can be found in the first four volumes of The Comics Journal Special Editions that Fantagraphics put out almost 10 years ago (feel old yet?). These are aggressive, at times even hostile comics, pushing the medium in odd directions (one strip is almost straight prose, save for a drawing or two of a young Gloeckner chiding the reader: "Bored yet? If so, go away!"). My favorite is the one about prostate exams.

In other media, Diary of a Teenage Girl was adapted into a stage play a few years ago. I haven't seen it but it won a number of raves and according to reliable sources is quite good.

For those looking to delve into Gloeckner's thoughts and processes, she gave an at times argumentative interview with Gary Groth back in issue #261 of The Comics Journal. The interview's up at the Journal's website, so you don't have to go digging through back issue bins. You can also find some other interviews with Gloeckner here and here.

Avoid

Absolutely nothing. All of Gloeckner's work to date has been stellar.

Next month: Marjane Satrapi