Comics College is a monthly feature where we provide an introductory guide to some of the comics medium’s most important auteurs and offer our best educated suggestions on how to become familiar with their body of work.

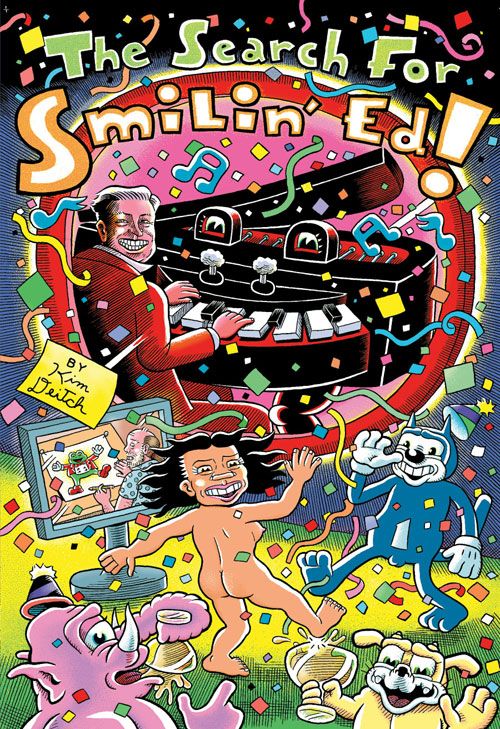

A rotten sinus cold/upset stomach plus an ungodly amount of day-job work has kept me from event attempting to work on Comics College. Thankfully, the ever-erudite Bill Kartalopoulos graciously volunteered to write this month's entry, about the legendary underground cartoonist Kim Deitch. And it just so happens that Bill's the perfect person to write about Deitch and his legacy, as he curated a show featuring the artist at MoCCA not too long ago and also wrote the intro for Deitch's latest book, The Search for Smilin' Ed.

So with that, I'm going to take some Advil and lie down. I leave you in Bill's more than capable hands.

Why he’s important

Kim Deitch is an enormously vital and prolific cartoonist who was also one of the charter members of the underground comix scene that changed comics in the 1960s and 70s. Even before underground comic books were popularized with the 1968 publication of Robert Crumb’s Zap #1, Deitch was part of a group of cartoonists contributing early underground comic strips to countercultural newspapers like the East Village Other. From the beginning, his style showed the influence of early American animation, and his stories featured wild flights of fancy rooted in comics’ satirical traditions, tinged with psychedelia, and shot through with an earnest sympathy for the human character in all its eccentricity.

More than forty years later, Deitch stands as one of the few underground cartoonists who has steadily and consistently produced a large body of important work, spanning every available format from the alternative weekly comic strip to the graphic novel. Even more strikingly, Deitch has built upon each successive story to spin a complex, career-spanning yarn of interrelated stories that refer to and amplify one another, while mixing fact and fiction to include Deitch himself as a character in his own narratives. These comics are all rendered in brilliant, heavily cross-hatched black and white artwork, and his frequently mind-blowing page compositions pulsate with radiant intensity. In recent years most of his major works have been collected and reprinted, making it possible for readers to explore this significant body of work by one of this country’s great cartoonists.

Where to start

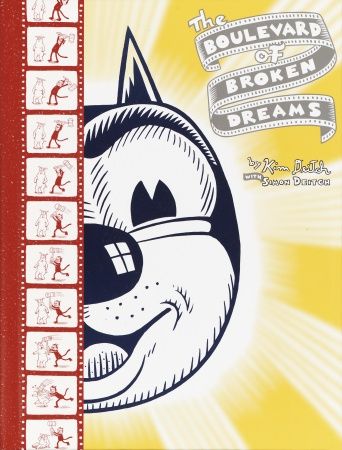

The Boulevard of Broken Dreams is Deitch’s most immediately accessible major book. Starring his signature character Waldo the Cat, Boulevard is a historical fiction revolving around the early animation industry of the 1920s and 1930s. Featuring some brilliant sequences that play with the formal distinctions between animation and comics, the book follows several generations of characters to meditate on the human and cultural legacies of industrialized art. Collected in a beautiful hardcover edition by Pantheon several years ago, this book unfortunately seems to be on the brink of slipping out of print, but remains findable for now.

From there you should read

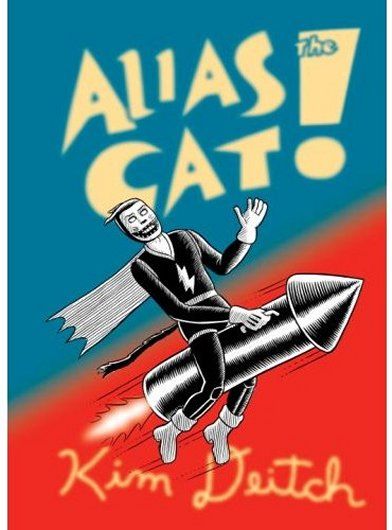

Although all of Kim Deitch’s comics work together to highlight different aspects of his vast fictional world, there is no true beginning or endpoint. Alias the Cat isn’t exactly a sequel to The Boulevard of Broken Dreams, but it’s a major (and majorly underrated) graphic novel that, among other things, will catch readers up with Waldo’s more recent exploits. The book itself plunges Deitch — the character — more directly into his own story, and includes a comic-within-the-comic, a fictional silent film star acting as a pacifist superhero, high seas adventure, and a journey to the heart of old Midgetville. The book also exhibits Deitch’s fascination with Victorian illustrated literature, featuring an illustrated text interlude and fine crosshatching throughout that shows the graphic influence of wood-engraved illustration.

Anyone wondering just who — or what — Waldo is, and why he keeps popping up, must read A Shroud For Waldo, originally serialized in an alternative weekly newspaper (and presented in a page-by-page episodic format). Shroud details the strange, surprisingly familiar origins of this apparently immortal anthropomorphic cartoon cat. This information will come in handy later. Guest starring Jesus Christ.

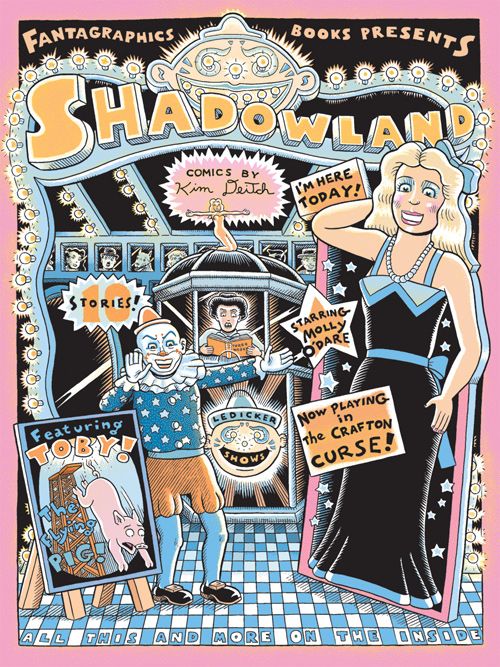

From there, you’ll want to explore the other major strand of Deitch’s work beginning with his graphic novel Shadowland. This book extends Deitch’s exploration of the backstage world of American popular entertainment to the pre-cinematic era, tracing the history of medicine show impressario Doc Ledicker and his extended family, and spiraling outward into a weird science-fictional world that treats history as entertainment and entertainment as history. This slightly oversized book is a great showcase for Deitch’s detailed artwork, and includes a full color fold-out section in the back.

Although it’s not Deitch’s most recent work, his most recent book collection The Search for Smilin’ Ed, among other things, brings the various major strands of Deitch’s world together. Deitch’s quest to discover the fate of a (quite real) 1950s children’s television show host sets the stage for the inevitable meeting of Doc Leidicker, underground comix stalwart Miles Microft, Waldo the Cat, and, indirectly, Deitch himself. This book also features a stunning full-color double-gatefold image of “The Kim Deitch Universe,” conveniently labeled for ease of use.

Further reading

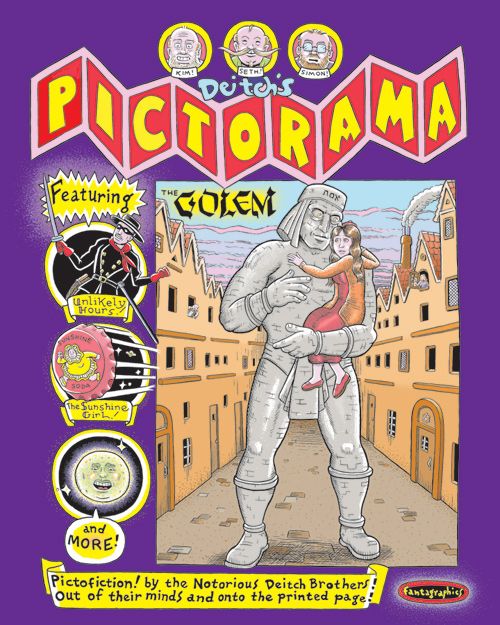

Deitch’s most recent collection of all-new work, Deitch’s Pictorama, isn’t exactly comics, but explores the concept of the “graphic novel” by featuring a suite of heavily illustrated short stories by Deitch and his two brothers, Seth and Simon, in various configurations. This book nearly flips the typical text-to-image ratio of most illustrated novels, featuring some beautifully chaotic nearly full- and double-page images by Deitch that rival the greatest drawings of his career. The showstopper story “The Sunshine Girl” depicts Deitch’s encounter with the (fictional) afterlife of his titular underground comix character, and sows the seeds for his current work in progress, a full-on landscape-format illustrated novel that’s sure to be a knockout when it’s completed and published. (For those on Facebook, Deitch has been posting some preview images here.)

For a different kind of Deitch story, I’d recommend his sensitive comics reportage piece “Ready to Die!” about the last days of a death row inmate, originally published in Details magazine and later anthologized both in McSweeney’s #13 and The Best American Comics 2006.

Ancillary material

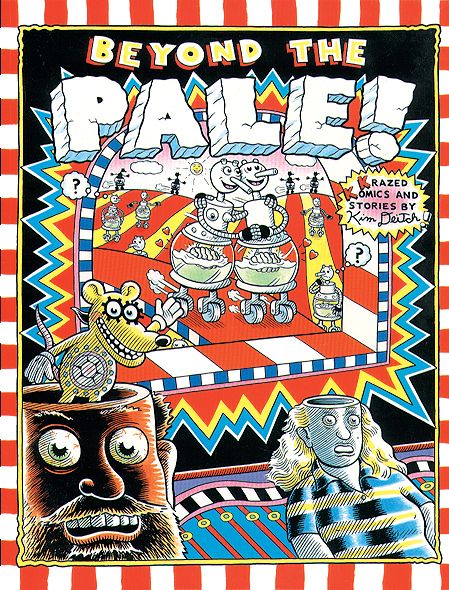

Beyond the Pale collects several of Deitch’s best short underground and post-underground comics. It’s a bit of a grab bag, but it provides some of the funkier flavor of his earliest comic book stories (including an epic Miles Microft saga from his underground comic book Corn Fed #2) and there are many gems here, including some great stories from Arcade, an amazing gatefold image called “Anthropomorphism,” and “Two Jews From Yonkers,” an autobiographically-based account of his early cartooning career that was also his first foray into heavily illustrated fiction.

Beyond the Pale includes a nice introduction by Deitch in which he discusses his early history and career in comics up to that point. For a truly massive career-spanning interview, you’ll want to pick up the book-length Comics Journal #292, which is almost entirely devoted to interviews with Deitch, his father, animator Gene Deitch, and his two brothers. Much shorter but also very much worth reading is Deitch’s interview with Zak Sally in Comic Art #5.

Before A Shroud for Waldo, Deitch’s first weekly serial was Hollywoodland, a kind of love note to old Hollywood that chronicles some strange doings surrounding the La Brea Tar Pits. The story features ex-screen star Larry Farrell, a minor character in several of Deitch’s other works. It’s only tangentially connected to Deitch’s other narratives, but is, as always, a really fun, imaginative story.

For visual kicks, readers may want to seek out Pictopia #2, which includes a Boulevard-related story that didn’t make the final cut, as well as some amazing, full color pseudo-animation cells from Waldo’s “career” as an animation star. (There’s also an animated version of the story online here.) Additionally, Deitch’s three-page story in the massively oversized Kramers Ergot 7 offers a bit more background detail to his “Sunshine Girl” story and retells some of those events from a slightly different perspective — but this time at large size and in full blazing color. Deitch has also done some fun work for kids (some may recall his “Southern Fried Fugitives” series for the late Nickelodeon Magazine), including the full-color story “These Cats Today!” collected in Big Fat Little Lit.

Avoid

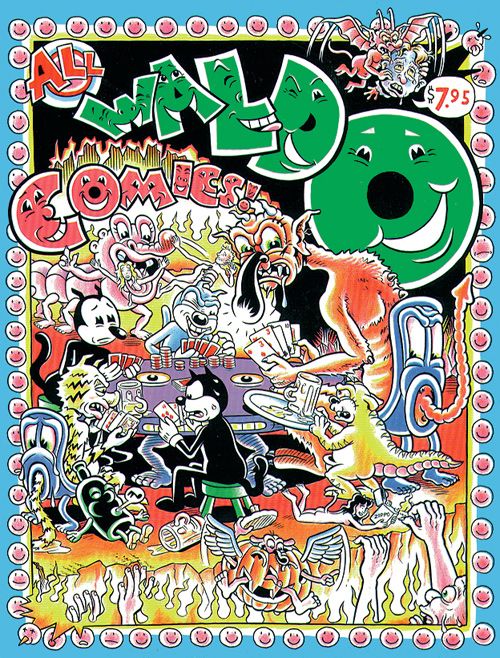

I hope it’s clear by now that even Deitch’s minor works often illuminate some glimmer of his massive fictional universe, and anyone who’s been seduced by this work will want to read it all. As such, I’m reluctant to suggest “avoiding” anything, but if I have to pick something for this category I’ll suggest that all but the most dedicated readers can skip the slim book collection All Waldo Comics. Which isn’t to say that the book doesn’t have some things going for it, including a great cover, some fascinating sketches, and a fun, sharp looking Waldo story from RAW that hasn’t been reprinted elsewhere. However, the book also includes an illustrated text piece about the inspiration for Waldo that was later reprinted as an opening sequence in The Boulevard of Broken Dreams, and a prelude to A Shroud for Waldo that may only be of interest to devoted readers. For true “Deitch-ologists,” the real interest here may be an early Waldo saga called “Deja Vu” that reveals at least one major fact about Waldo the Cat. However, the story was originally printed in a beautiful three-color process in Gothic Blimp Works, to which the black and white version in this book does no justice. I hope that some day this piece of arcane Waldo lore will be reprinted the way it was originally meant to be seen. In the meantime, I’m grateful that the last ten years of comics publishing has produced such a bounty of Kim Deitch books that we get to pick and choose.

Next month: Kevin Huizenga

Bill Kartalopoulos teaches courses including “Reading Graphic Novels” and “Comics History” at Parsons The New School for Design in New York City. He is the Programming Coordinator for SPX: The Small Press Expo and the Programming Director for the Brooklyn Comics and Graphics Festival, is a contributing editor for Print Magazine and a comics reviewer for Publishers Weekly, and sits on the Executive Committee of the International Comic Arts Forum (ICAF). This year he curated R. Sikoryak: How Classics and Cartoons Collide at the Museum of Comic and Cartoon Art. In 2008 he curated Kim Deitch: A Retrospective, also at MoCCA, and more recently contributed a lengthy introduction to Deitch’s 2010 graphic novel The Search for Smilin’ Ed.