Comics College is a monthly feature where we provide an introductory guide to some of the comics medium’s most important auteurs and offer our best educated suggestions on how to become familiar with their body of work.

Strap yourself in for a long read, because this month we're looking at the rather lengthy and considerable career of one of the most influential comics creators of the past 40 years, Mr. Frank Miller.

Why he's important

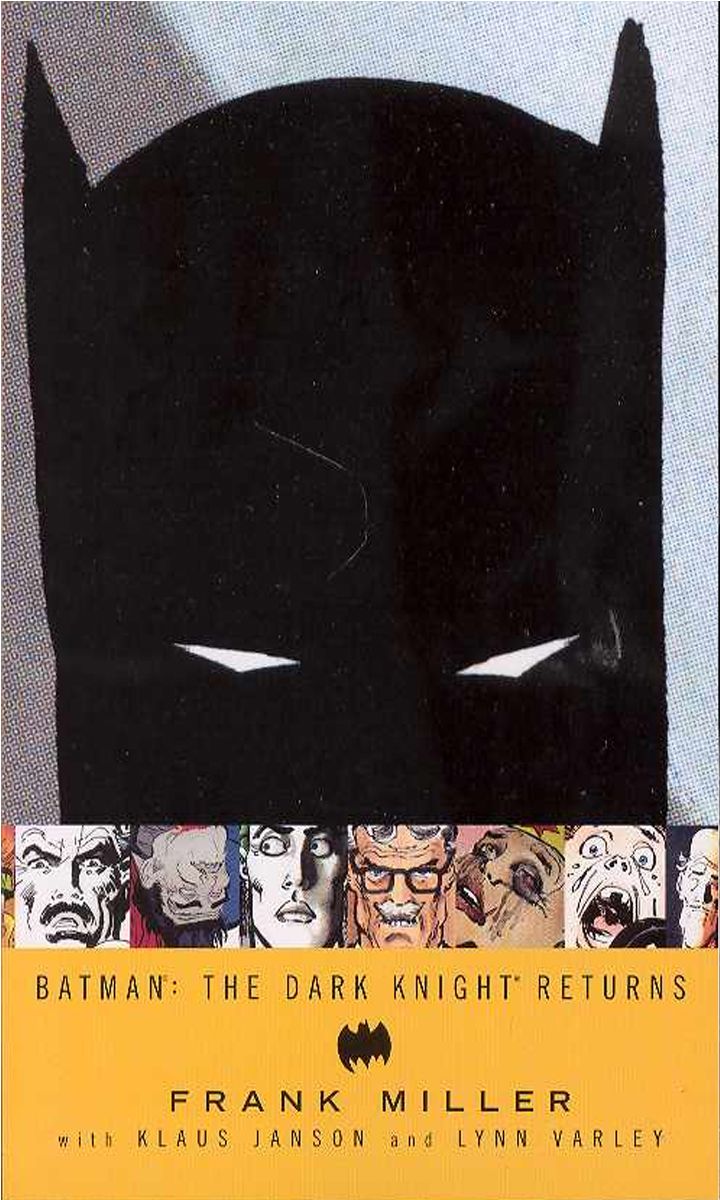

Back in the 80s, there where three books every media pundit trumpeted as the high-water example that comics weren't just for kids anymore: Maus, Watchmen and Miller's Dark Knight Returns. While that pairing may seem odd and slightly reductive today (and it did for many then), there's no question that Miller's work helped many creators and fans, both in the superhero mainstream and outside it, think beyond the perceived limitations of the medium and helped drag comics kicking and screaming into the modern day.

Aesthetically, he's one of the most exciting and dynamic creators working in the field today. While even his best work has its share of flaws and his worldview can be ... overly simplistic at times, he is never boring.

Where to start

It may seem like a cliche, but his best known and arguably most beloved work -- The Dark Knight Returns -- is the best place for new readers to be introduced to Miller's work. All of Miller's tropes are laid out right there on the page. The superhero fused with noir ethos; the clipped, terse dialogue; the tiny panels that bleed into a huge splash page, the sketchy, delightfully rumpled line (nobody draws trenchcoats like Miller); the TV screens that doubled as panels. If Daredevil made Miller a star and Ronin showed what he was capable of, Dark Knight showed how he could apply his style to the superhero genre, and has served as a framework of sorts for his work since then (not to mention ushering in a host of lesser copycats, but let's not blame him for that).

From there you should read

Some people will tell you that Dark Knight Returns is Miller's finest work. Those people would be wrong. Miller's best work by far -- no question about it -- is Ronin, sci-fi post-apocalyptic saga that combines all of the artist's influences at the time -- Lone Wolf and Cub, Heavy Metal, Will Eisner -- and whips it up into a tense, delirious froth.This was Miller's chance to show everyone what he was truly capable of, what he could do if the restraints were taken off, and he went full throttle. While he's certainly produced good -- even great -- work since then, he's never equaled what he achieved with Ronin.

Of course, Miller is known just as much for his collaborations as he is his solo work. Easily his most fruitful collaboration proved to be with David Mazzuchelli, who worked with him on the excellent Batman: Year One and Daredevil: Born Again. The former retells Batman's origin by way of Dashiell Hammett, while the latter throws DD through an emotional wringer, pulling apart and examining the tenets of heroism and villainy. Both exhibit some of Miller's best writing to date and more than earn the high reputation they have among fans, both in and outside the traditional superhero club walls.

Further reading

One book not many Frank Miller fans seem to talk about a lot is Elektra Lives Again, which kind of seems like a shame since it's a great read, an intense fever-dream of a book featuring some truly stellar fight sequences. True it doesn't make much sense, but what it lacks in that department it more than makes up for in style and nerve. Really, it's about due for a critical re-evaluation any time now.

Moving on, we come to the Sin City line, Miller big, blood-soaked valentine to the noir and hardboiled crime genres. These books don't really fit in the noir mold per se, they lack the sense of tragedy and helplessness that noir requires; they're more like noir hopped up on steroids. Still, at their best they have a propulsive energy and vision that is rarely matched in comics. And it is delightful to see Miller see how far he can take his black-and-white ethos on the page.

The books vary widely in quality, but even so, it's best to read them in order as the stories tend to bleed into each other to some degree. So, in chronological order you have: The Hard Goodbye (great), A Dame to Kill For (awful, one of his worst books ever), The Big Fat Kill, (great) That Yellow Bastard (good), Family Values (meh), Booze, Broads and Bullets (whatever) and Hell and Back (flawed but deliriously nutty, and points the way towards later work like Dark Knight Strikes Again).

In between Family Values and Hell and Back, Miller put out 300, a gung-ho, chest-thumping saga about the Battle of Thermopylae. It's more concerned with macho bravado than historical accuracy, but it is one of the most visually striking books he's ever done, a large part of which is thanks to the work of his ex-wife, colorist Lynn Varley (who, frankly, doesn't get nearly enough credit for her work as Miller's collaborator).

After Varley and Mazzuchelli, Miller's other best collaborator would have to be Bill Sienkiewicz, who helped put together the trippy Love and War and Elektra: Assassin, both of which are collected in the now out-of-print Daredevil/Elektra Love and War hardcover. Love and War is a conventional Daredevil story told from the perspective of one of Miller's off-kilter madmen (what is it with Miller and eggs anyway?), while Elektra: Assassin, is just plain, off the wall loopy. It's wilder elements seem rather tame by today's standards (it's hard to believe people actually were up in arms over this book) but it still holds up as a great read.

Even further reading

Many readers and critics didn't know what to make of The Dark Knight Strikes Again when it first came out and it can definitely be an off-putting book for those expecting something more straightforward and serious, like the first Dark Knight book or 300. But taken on its own terms it's great fun, a rough, raw, big-footed attempt to make superheroes goofy and fun and snappy again. Don't try to make too much sense out of it, just let it wash over you.

Miller got made his name back in the 1970s on Daredevil, and that extended run is collected in Daredevil Visionaries Vol. 1-3. Frankly, of all of Miller's work I think this holds up the least. You can sense him chafing at the bit, frustrated by the conventions of the era, especially towards the end of his run. (Why doesn't DD just go ahead and kill the bad guy? Why can't we raise the sex and violence quotient? Do I have to reintroduce DD's secret origin and powers in every issue?) But if you want to see where Miller got his start, this is where you go.

Miller returned to Daredevil yet again with John Romita Jr. for Daredevil: The Man Without Fear, an attempt to do for Matt Murdock what Batman: Year One did for Bruce Wayne. It's nowhere near as good as that book, but it's still a pretty tight, grim read, and well worth checking out for Romita's visuals as much as Miller's prose.

In 1990, Miller introduced the world to artist Geof Darrow with the release of Hard Boiled, another over the top action set piece that starts with a wonderfully surreal bang but quickly deteriorates into a standard "man against oppressive forces" plot, though it still retains some comic punch by the end. Miller and Darrow followed that up with The Big Guy and Rusty the Robot, a parody of classic Japanese monster movies and old-school superhero comics that feels strangely reined in by both parties. Both books are worth reading if for no other reason than to feast upon Darrow's hyper-articulate, to-hell-with-negative-space art, but neither book qualifies as essential.

Ancillary material

Miller is many things, but subtle isn't one of them, which makes him a very poor satirist. This is best evident in the series of books he did with Watchmen artist Dave Gibbons -- Give Me Liberty, Martha Washington Goes to War, Martha Washington Saves the World and Martha Washington Dies, all of which are collected (and then some) in The Life and Times of Martha Washington in the Twenty-First Century. While Gibbons art is stellar, the story itself is limp. Miller goes for big, obvious targets and his arguements (liberals mean well but are ineffectual; republicans are corrupt, evil bastards; you have to fight and risk all for what you believe in) seem tiresome and rote here.

Going back in time, The Complete Frank Miller Spider-Man collects a number of unrelated Spidey stories Miller drew but didn't write for Marvel back in his early days at the company. Those who like Miller's art work, particularly his early style, will enjoy this, but there's nothing exemplary here.

Miller parodied his own macho blustering in Tales to Offend, which, while more than a trifle obvious, is the one exception to the "bad satirist" rule.

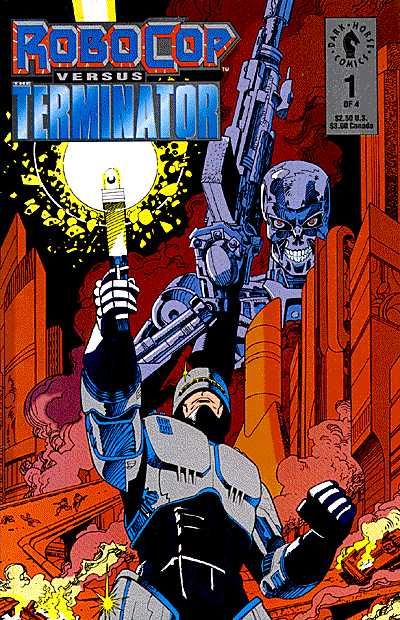

Way back in 1992, Miller teamed up with Walt Simonson for the four-issue Robocop vs. Terminator, a fitfully amusing spin-off that never achieves true lift-off, but has some neat moments, especially in playing with the "the past has changed the future! now we must go back into the past again" time-travel hokum.

Speaking of Robocop, Miller ia no stranger to Hollywood, having written the screenplays to Robocop 2 and Robocop 3, both of which apparently were heavily futzed with (Avatar Press adapted the original scripts into comics if you're curious). Successful adaptations have also been made of Sin City (which he co-directed) and 300 (though Sin City is by far the better adaption). Those successes led Miller to try to direct a movie on his lonesome, a crazy-quilt version of Will Eisner' The Spirit, which, while visually striking and -- again -- far from boring, is a truly awful film.

There aren't a lot of critical writings available on Miller, at least not in print, but interested parties are encouraged to check out The Comics Journal Library: Frank Miller, which contains a number of interviews Miller did for the Journal at various points at his career.

Avoid

Let's see, I already mentioned A Dame to Kill For, right? That would leave Spawn/Batman, a ugly, cynical team-up with Todd McFarlane that flatters neither contributor.

Then there's All-Star Batman and Robin. Fans of this series tend to regard it as a parody, but I don't think it is. It's self-aware and a bit tongue-in-cheek to be sure, but it revels in its trashiness a bit too much to be a simple parody. This is Miller attempting to "have fun" with Batman, which in this case means being as over the top as possible, which in turn results in a garish, obnoxious mess. Part of my problem with this work may be that I just don't care for Jim Lee's art very much. Certainly if you enjoy late-period Miller work like Dark Knight Strikes Again there's a good chance you'll like this as well, but this definitely isn't the place for newcomers to start.

Next month: Joe Sacco