AUCTION FOLLOW-UP

PIPELINKS AND PODCASTS

- In case you haven't heard enough about all the various controversies and craziness that happened in the comics world last week, give a listen to Surviving Creativity. Even though only Brad Guigar would agree with last week's Pipeline, I still enjoyed it a great deal.

- I haven't been involved in a controversy that nutty in a long time. Last week's column sparked quite the discussion on the CBR Facebook page. While there were dozens of commenters ready to skin me alive, the post still had close to 1000 likes, almost none of whom posted. I'm beginning to think Erik Larsen's "vocal minority" proved out with that post, though perhaps in the opposite direction than he intended.

- I'm not doing a full follow-up to that column because, honestly, most of the arguments written against it had nothing to do with anything I wrote. It was just people carrying over their assumptions and arguments from the hundreds of other flame wars on the Internet. So, moving on...

- This one goes back a couple of years, I think, but the interview with comics colorist Edgar Delgado over on the Paper Wings Podcast is a great one. He talks about breaking into the business as a colorist, why '80s movies looks different (color-wise) and Ultra Duck.

- From the show notes on that one: Here's a great step-by-step tutorial on coloring comics from Delgado, paying particular attention to how the light bounces around in a scene. (Go check out all the episodes of that podcast. There's lots of gold in those nuggets.)

- Not directly comics-related, but of interest to lots of people reading this, I'm sure: There was another one of those Internet tempests in a tea cup a couple of weeks ago when William Shatner couldn't make Leonard Nimoy's funeral. Mark Evanier has an interesting theory on that which makes Shatner out to be an even bigger hero. Read it.

HAND IT TO THE ARTISTS

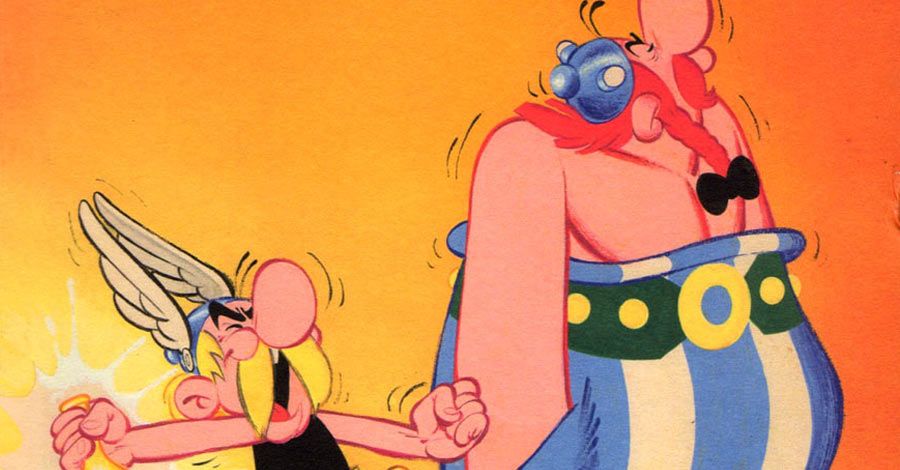

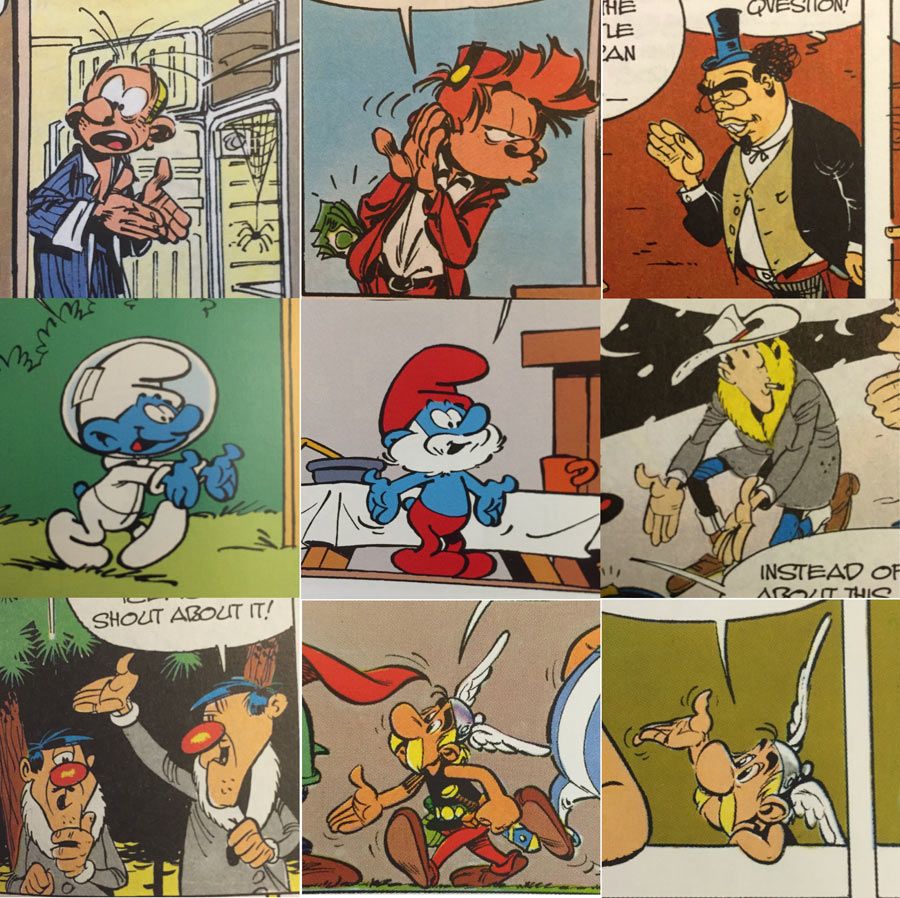

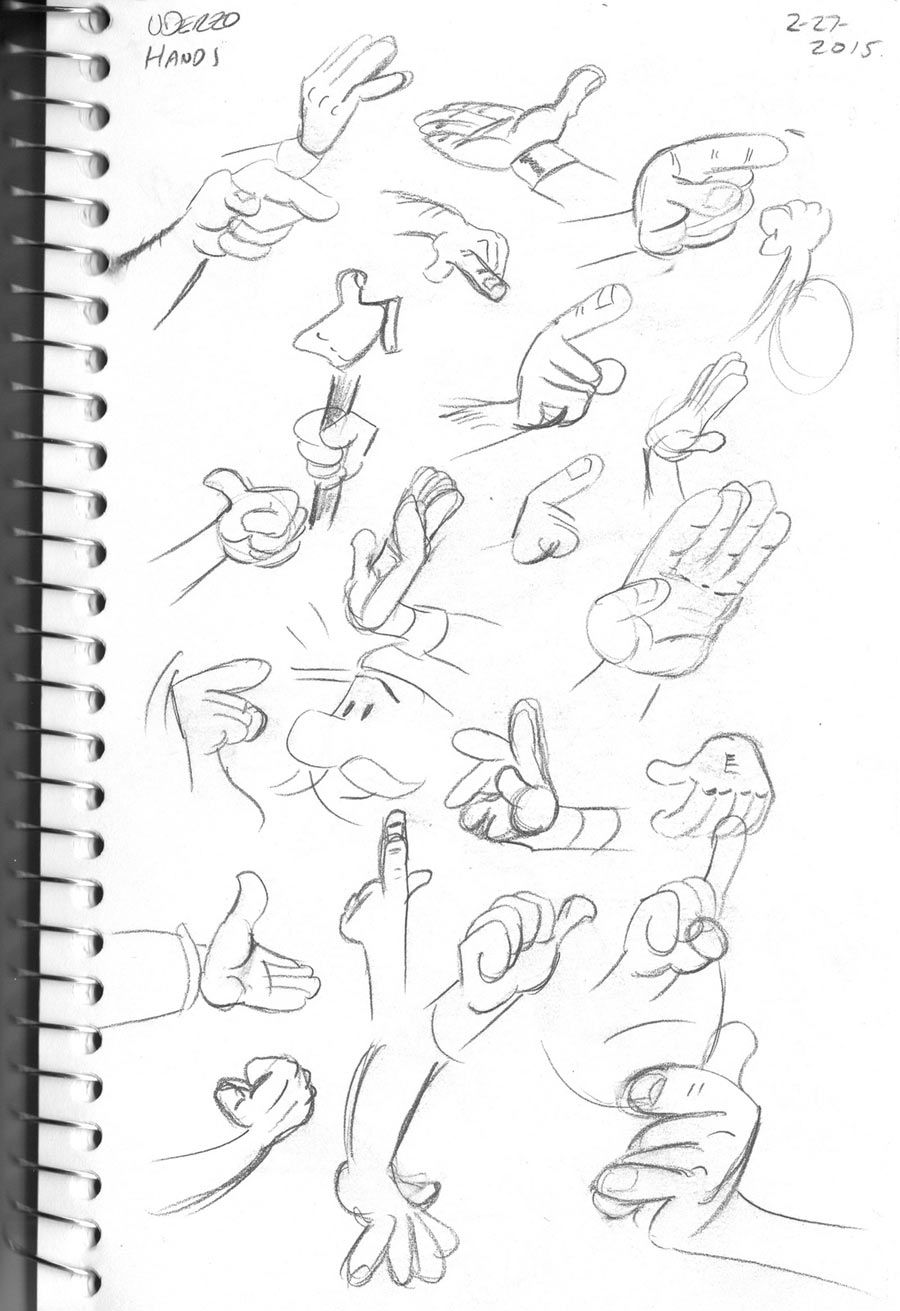

Asterix's Albert Uderzo and Lucky Luke's Morris come from the same style of Franco-Belgian art, the Marcinelle School. Their storytelling styles, their comedic sensibilities, and much of their pure art construction show that. Because I'm so enamored of that school, I set about last month to learn how to draw hands like they do. They're expressive and easy to understand. They have just enough proper anatomical elements to them that they feel real, but with enough added flair to make them stand out as something more.

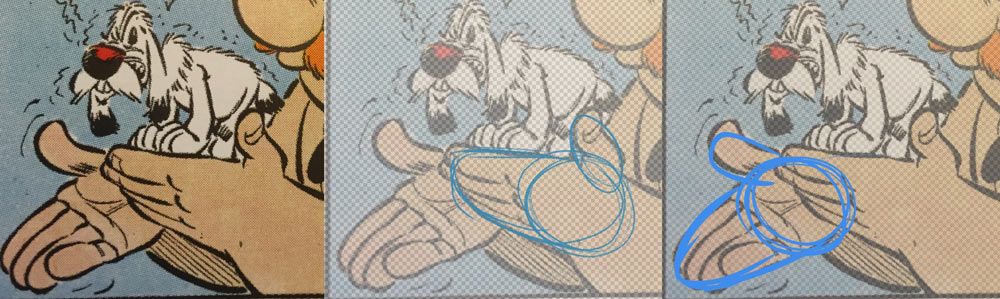

The basic construction is similar between Morris and Uderzo. Hands are a bit larger than normal. Fingers can be slightly squared off at the tips when seen at the right angles. Pinky fingers often bend slightly differently from the rest of the hand.

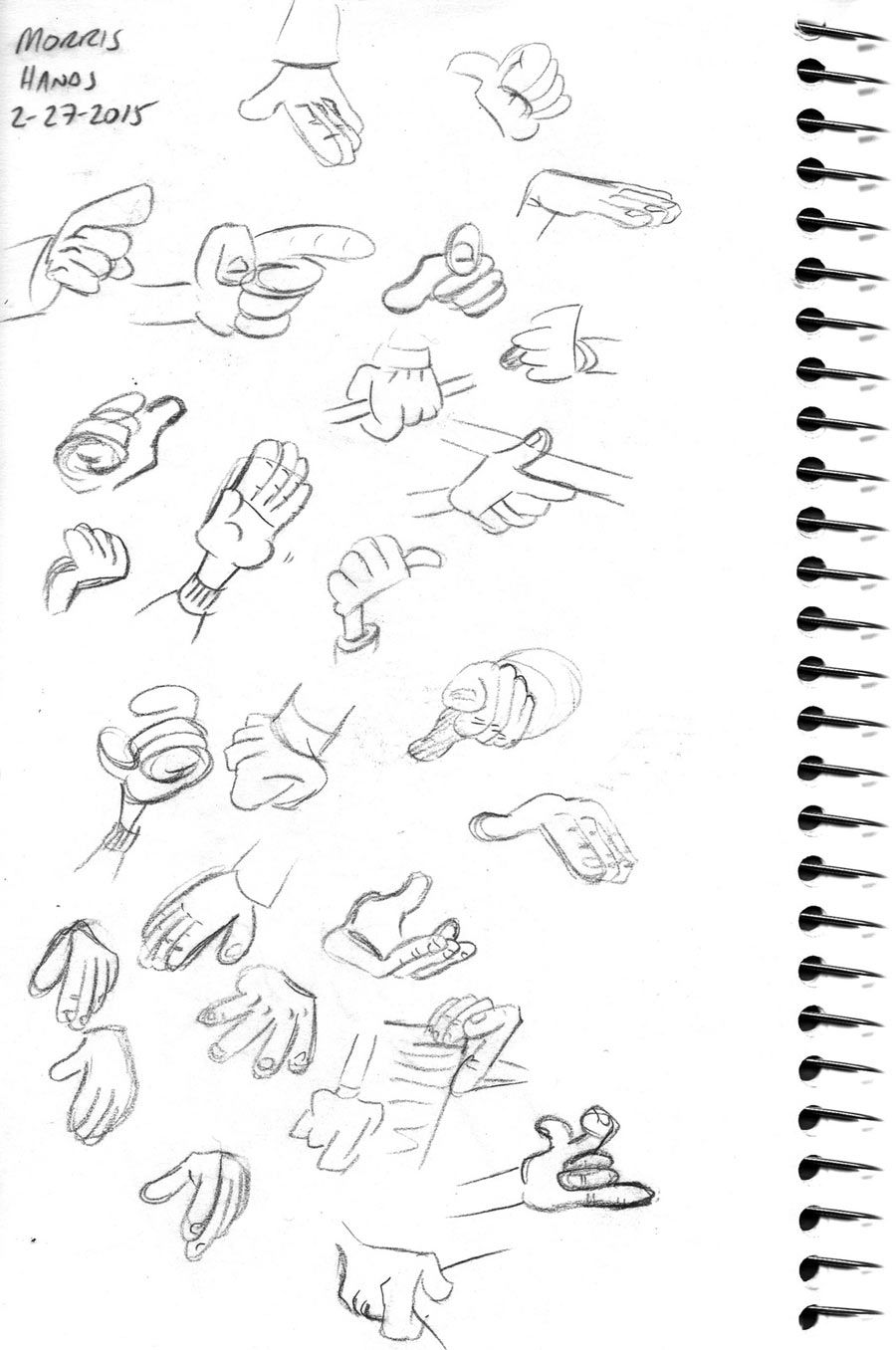

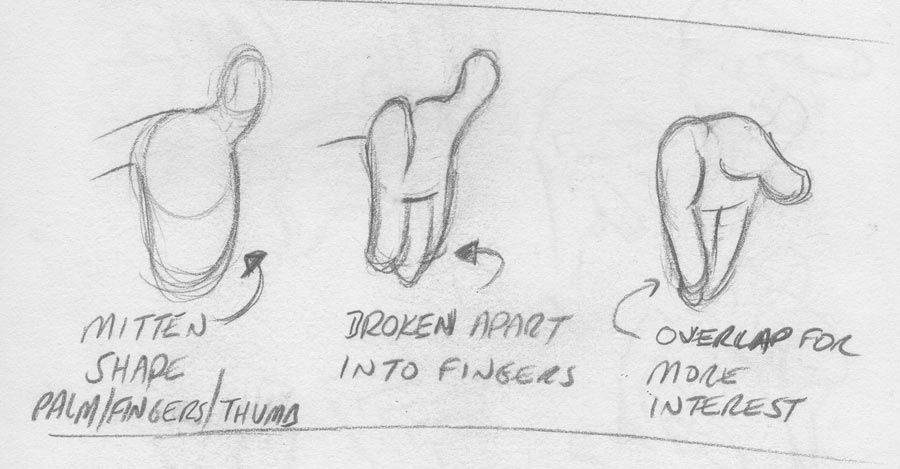

Morris' hands are more squared off, particularly at their base. He's capable of drawing skinny fingers and rounded hands, but his default hands feel more like square blocks with sausages for fingers. When the fingers are all together, you can get away with drawing a mitten and then dividing the proper parts into separate fingers. With an open hand where you can see the palm, you might want to start with a square to represent the palm and then build out.

While the hands from these different artists feel similar in ways, they're still vastly different in their overall effect. Peyo is the most cartoonish, fittingly, while Uderzo's hands are the closest to realistic, right down to the lines in the palms of the hands.

Uderzo's ink line also makes a big difference, I suspect. Uderzo's final lines are smoother, brushier. They vary line weight much more than Morris, whose hands often feel flat by comparison. So while Uderzo's hands might be the most "realistic," they just feel rounder just by the weight and smooth strokes of the ink lines.

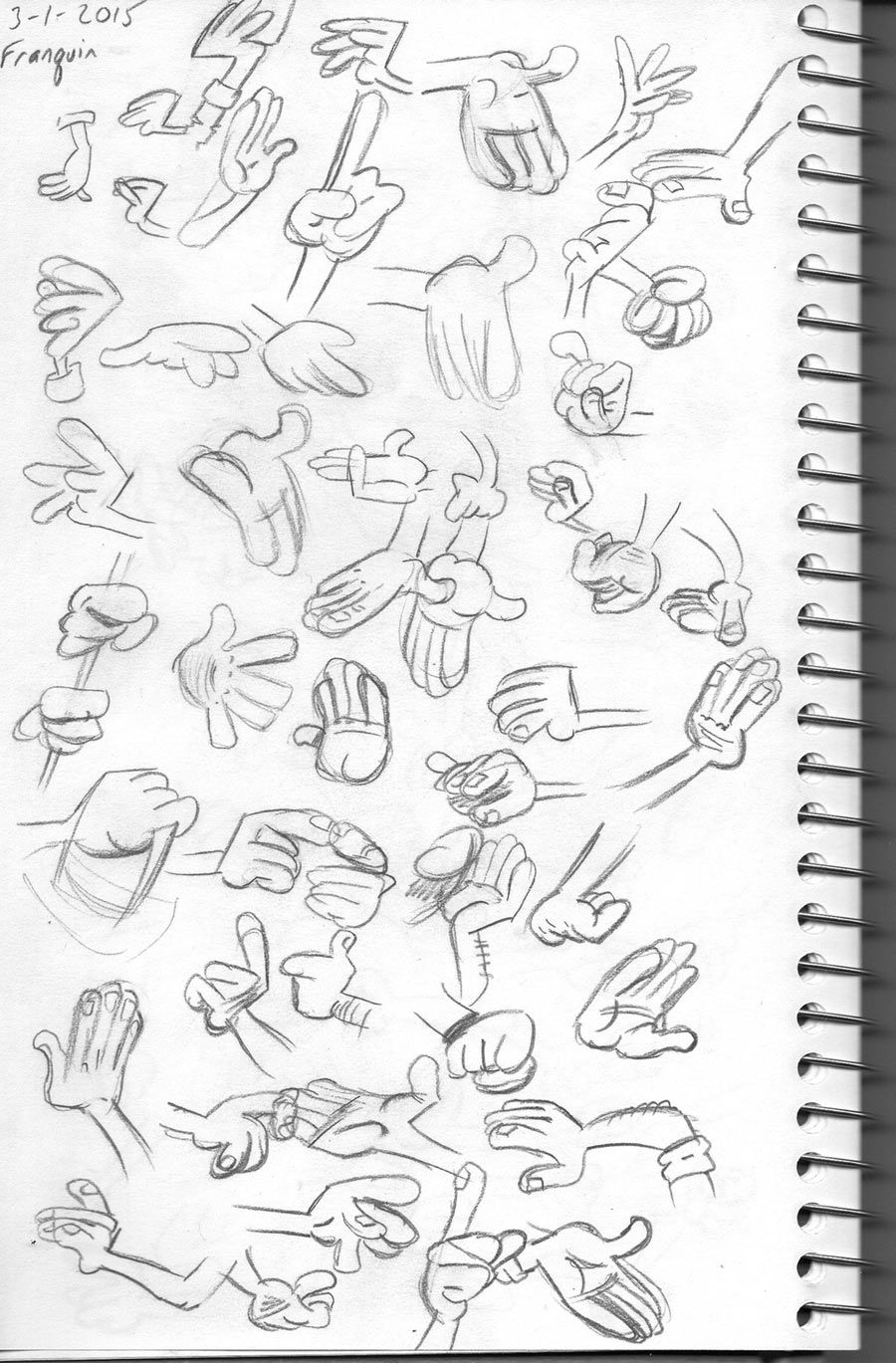

Franquin and his successors (like Batem and Tome) exaggerate it even more. The hands feel even larger, and the ink work gets larger, too. Line weights are heavier, knuckles are more pronounced, and some extra shadows are drawn in. There are some very heavy inks at work on some very exaggerated hands once you get to artists like Tome. Even Didier Conrad on his earlier "Les Innommables" was more ink-heavy, before he toned that down to look more like Uderzo's work for "Asterix and the Picts."

All of the above artists (minus Peyo) draw fingernails on their characters. They don't need to, since these are such cartoony images that such a seemingly-meaningless detail could be easily dropped out to keep the composition simple. But these fingernails are more than just bits of anatomy used to push the characters on the reader as being more human. No, they help sell the 3D image of the hand. The angle at which they're drawn gives you a better idea of the way in which the finger is twisted. The size, relative to the finger, helps show how big or small-handed the character is.

Everyone draws the knuckles (again, minus Peyo's Smurfs). With Uderzo and Morris, they're just a couple of lines to indicate the bends at the appropriate places, but they help break up the hand a little bit. The fingernails, though, serves more purpose, and I'd chalk the knuckle lines up to personal style, looking to break up the otherwise plain straight digits.

Morris' hands are also larger, proportionately to the rest of the body, than the other artists I looked at here. The wrists feel a little skinnier, and the hand overhangs the arm much more for it.

Practicing all these hands -- randomly from panels I'd turn the page towards -- I learned a strong lesson about "artistic vocabulary." That's a term I heard Jake Parker use in one of his recent videos, I think it was. It's the idea that the more you draw and the more you practice, the more tools you add to your tool belt. It's similar to the way a writer learns new words from reading and writing.

Those skills come out the other side during the act of creation when pasting together all these odd bits and bobs into something new and interesting. In Parker's case, he likes to draw spaceships. He can mix and match parts from the hundreds of ships he's drawn before to create a new one. Borrow a body shape from this one, a grill from that one, weaponry from another, and an antennae array from another. Presto! It's something new.

Drawing hands like this reminds me of how many positions a hand can take, but also of how few you really need to tell a story. Uderzo and Morris draw a lot in every volume of their respective titles. Each page can have 10 or 12 panels on them. Every panel will likely have at least two people on them, complete with their hands gesticulating and their faces emoting. But you know what? There aren't that many poses for their hands to be in. Seriously.

Drawing Peyo's Smurfs was the biggest eye opener in this exercise. He has 100 Smurfs to draw, all of whom are basically identical (save Papa and Smurfette). He draws dozens of them on every page. But the vocabulary of Peyo's hands doesn't run all that deep. I spent 20 minutes redrawing hands I saw in the "Astrosmurf" story and ran out of poses to use pretty quickly. I want to move forward in time now and grab a much later Smurfs story to see if those poses changed or morphed in any way. Were new ones added in as needed?

I'm not saying I've mastered them by any means. Peyo has specific quirks to his drawing, including the shape of Smurf fingers, which are usually tubes that are slightly square at the time with a little curvy bent to them. Fingers overlap each other in ways that you wouldn't notice at first until you try to deconstruct them and build them for yourself. And I can't, for the life of me, make a simple underdrawing to construct a Smurf hand with. There are times when the mitten approach works, but not that often. Peyo's hands vary in their structure, seemingly, from one angle to the next. Thumb sizes vary. Relative finger lengths come close to a human hand with the pinky being the shortest and the middle finger being the longest, but that's not always the rule. Peyo is pragmatic. He'll draw what looks good, even if it means occasionally pushing things around a little.

He's also by far the cartooniest of the artists I've copied from in this exercise. I need to try his non-Smurfs work next. As I recall, the Benny Breakiron stuff would have the same shape, but with slightly more "realistic" proportions. Also, since those characters are all human, they have five fingers per hand. You might notice in my samples above that even when I was copying from Uderzo, I often simplified it down to three fingers and a thumb. I like that construction for a hand, but that might owe more to my younger days of copying from Bugs Bunny cartoons...

If you're a budding artist looking for help in drawing hands, the best advice I could give you is likely the same advice everyone else has already given you: Draw more. On top of that, though, realize that it's not as bad a topic as you might have thought. You can get through a lot of storytelling with a relatively few poses. Having more helps, obviously, but it's not as big a hurdle as you might have thought. Once you get those first few hands down, you'll figure out how to push those fingers around and contort the shape into everything else you need.

Doing it consistently, though, just takes some time and effort. I still have a lot to learn, but I'm confident that I could get there now.

Next week: I'll review a comic book. Promise.

Twitter || E-mail || Instagram || DeviantArt || Pipeline Message Board || VariousandSundry.com || AugieShoots.com || Original Art Collection || Google+