The imminent arrival of Flex Mentallo -- a comic book few old-school Vertigo readers (myself included) ever expected to see collected in a fancy-dress trade -- has heartened Grant Morrison fans and lovers of lost comic causes everywhere. If that comic can finally see the day, perhaps there's hope for all sorts of beloved but forelorn projects. With that in mind then, let me present to you another Grant Morrison comic that has lingered unfairly in obscurity ever since its The New Adventures of Hitler.

Lest you think that title is some sort of ironic joke or that the book doesn't actually involve the person mentioned in the title, much in the same way Joyce's Ulysses isn't about the Greek hero (at least not on the surface) let me assure you, this is a comic book about the Adolf Hiter.

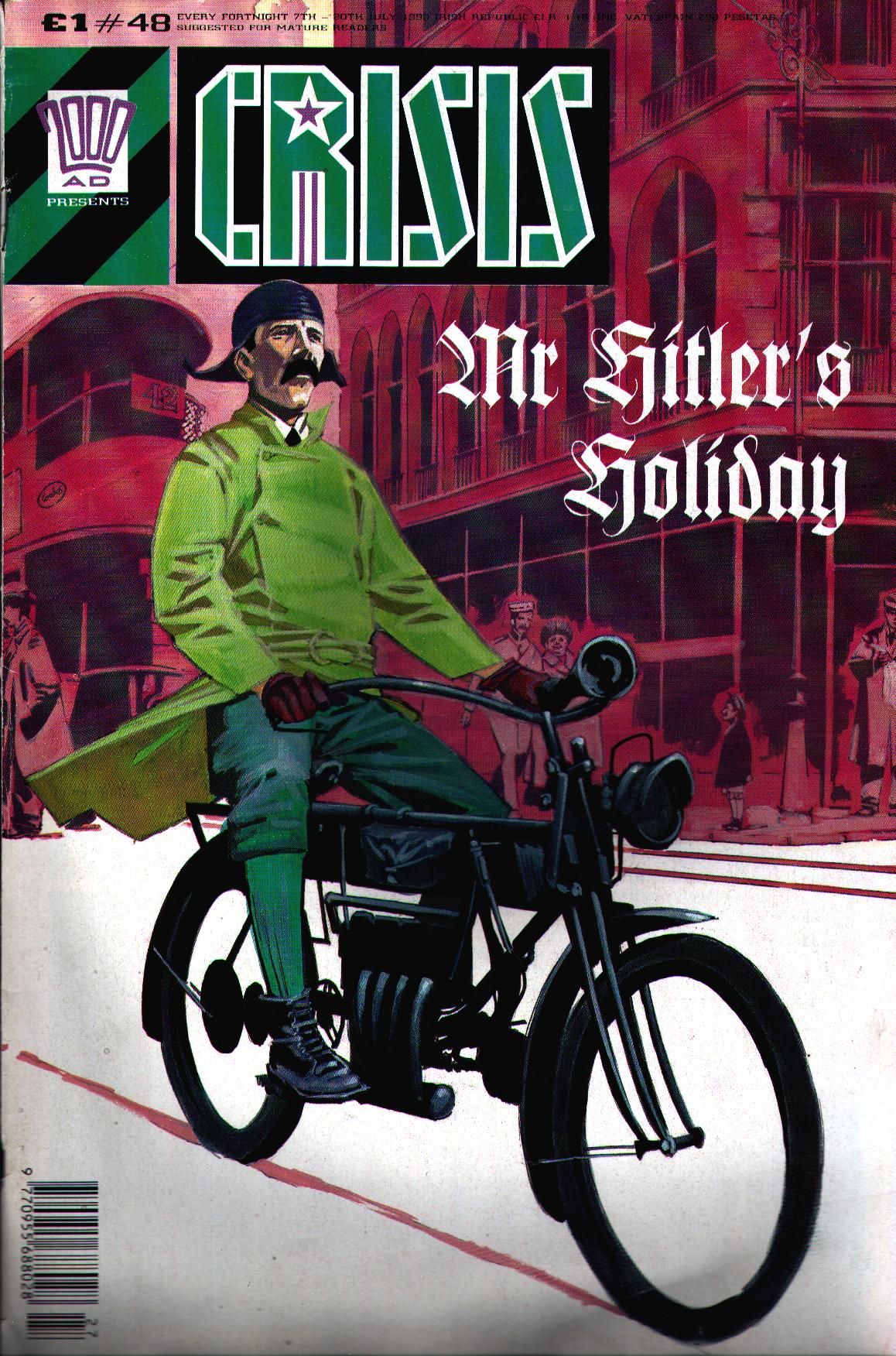

Morrison's story is based on a (extremely dubious) claim made by Adolf Hitler's sister-in-law Bridget Dowling that the future leader of the Third Reich had lived with her, her husband, Alois, and their young son in Liverpool, England, for a brief time between 1912 and 1913. Morrison's story runs with that premise and imagines a shiftless and down on his luck Adolf roaming through the Liverpool streets, consulting with fortune tellers and generally embarrassing his family, who consider him a slacker doomed to forever sponge off relatives while dreaming of grandeur.

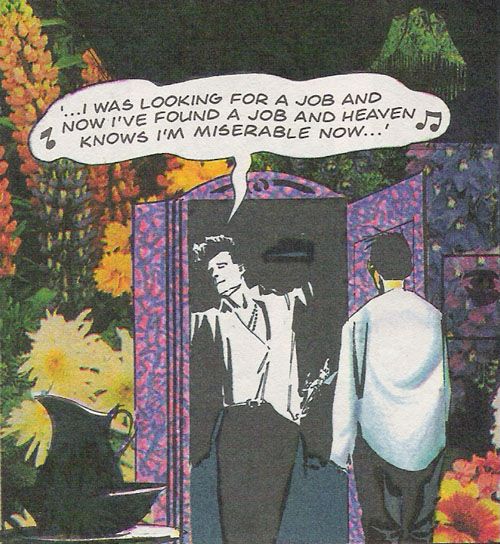

Now, lest you have any fears at this point that Morrison portrays Hitler in anything resembling a sympathetic manner, allow me to put them to rest. The Hitler portrayed here is little more than a hallucinating (early on in the story he opens his closet to find Morrissey there singing "Heaven Knows I"m Miserable Now") madman and buffoon, albeit a dangerous one since, for all his bizarre behavior and paranoia, he quickly grows to understand how to best exploit people's basic needs and fears in order to serve his own mania for power and make the world fit his view of how things should be. No, this story is not some awkward attempt to "understand" the most hated man in the world but more of a warning to modern readers about how Hitler was one man in a long line of certain types of people are always ready to take advantage of the rest of us if we allow them to.

The political allusions are obvious and somewhat ham-fisted. At one point, for instance, a giant image of Margaret Thatcher peers through a window as John Bull, the British version of Uncle Sam, tells Hitler how the country needs a "mad, vicious bitch in the driving seat." But if Morrison's text stumbles on occasion, Steve Yeowell's surreal art is more than ready to do the heavy lifting. While alternating between a basic four and six-panel grid, Yeowell, along with colorists Nick Abadzis, Steve Whitaker and John Buckle, fill this universe with an almost-oppressive psychedelic design that only serves to heighten the surreal atmosphere. Bright paisley and garishly flowery wallpaper overwhelm the rooms to the point where they run over the furniture and even at times the people. Brown and grey watercolor washes sweep across the panel allowing for not a single bit of vibrancy. It is one of the most original and stunning coloring jobs I've ever encountered in a comic.

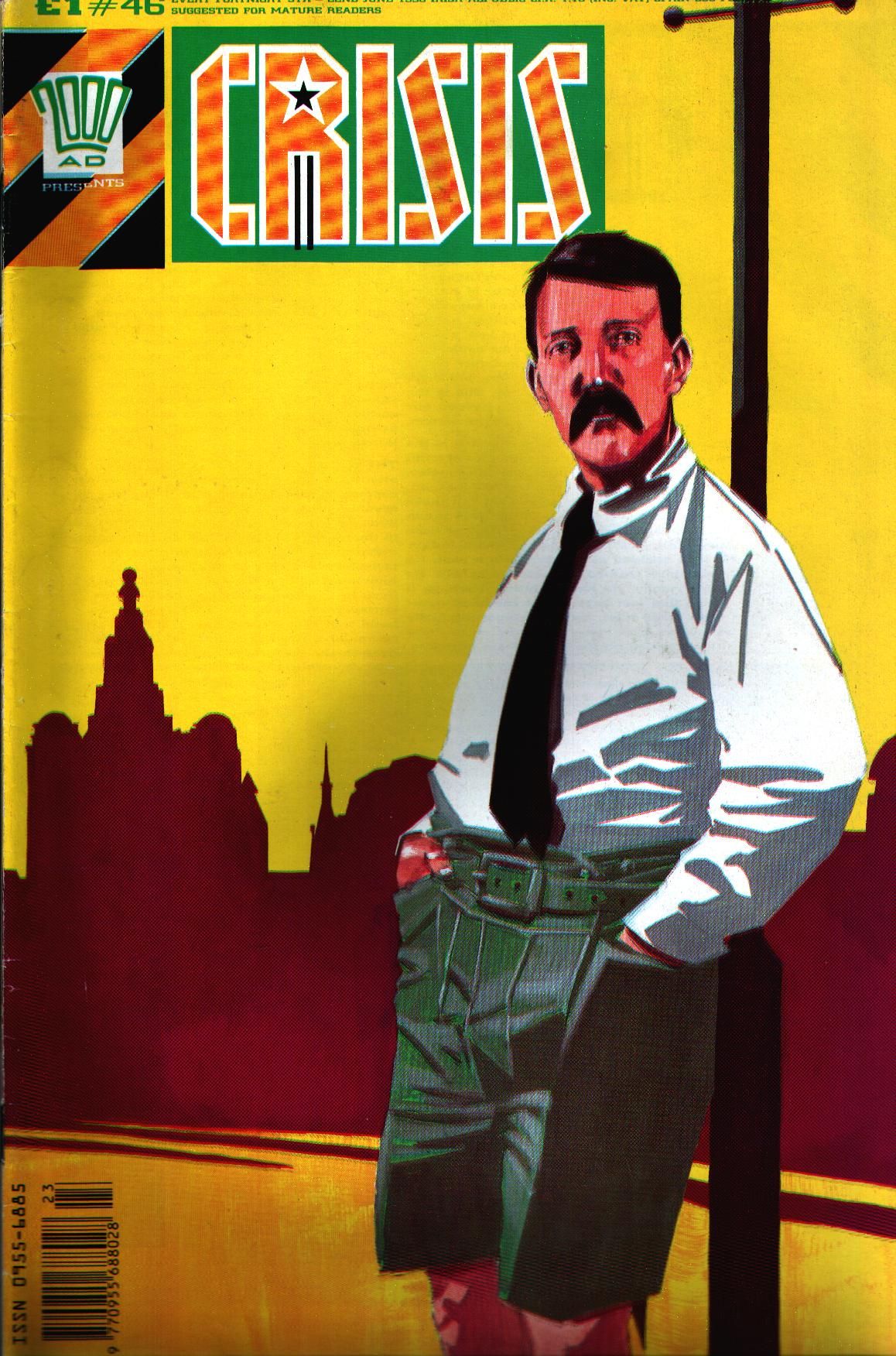

Hitler was serialized twice in the U.K. back in 1989 and 1990 but has never been collected since and it's not too hard to figure out why. The comic initially ran in a Scottish comics magazine entitled Cut, where it immediately got into trouble as one of the editors threatened to quit and national tabloids swooped in to cover the controversy. It then ran in the U.K. comics magazine Crisis (a spin off of the ever-popular 2000 AD anthology magazine) in issues 46-47, where it almost immediately garnered controversy again, as people falsely accused Morrison of either using the Holocaust and Hitler to garner attention or, worse, being a neo-Nazi.

Neither is true of course. While The New Adventures of Hitler may not be as exemplary a work as Flex Mentallo, it remains a compelling, fascinating and occasionally disturbing read, a fine example of Morrison's early work, with hints of the sort of material he'd explore in books like Doom Patrol and The Invisibles. Up till now the only way to read this comic was to either try to track down old issues of Crisis or download a pirated version. I ended up taking the latter route, but I'd prefer and gladly pay money to get my hands on a collected edition.