Occasionally an editor hangs on to samples that artists send him, afraid they may never see this material again. Somewhere in my files, I have little gems sent to me by sometimes famous artists, sometimes soon-to-be-famous artists, and somewhere, I may still have some that never became either, young hopefuls that never carried through or people who I failed to find a place for.

Francesca Ghermandi is one of the people whose packages I cherished when they used to come to me. I think she wrote me twice, and as a result, I have copies of Helter Skelter and Hiawata Pete, both in Italian, both absolutely brimming with amazing cartooning. These would be great candidates for that Robot 6 column where they demand books get translated, and boy, I'd sure love to read them someday. For now, I just look at the pictures.

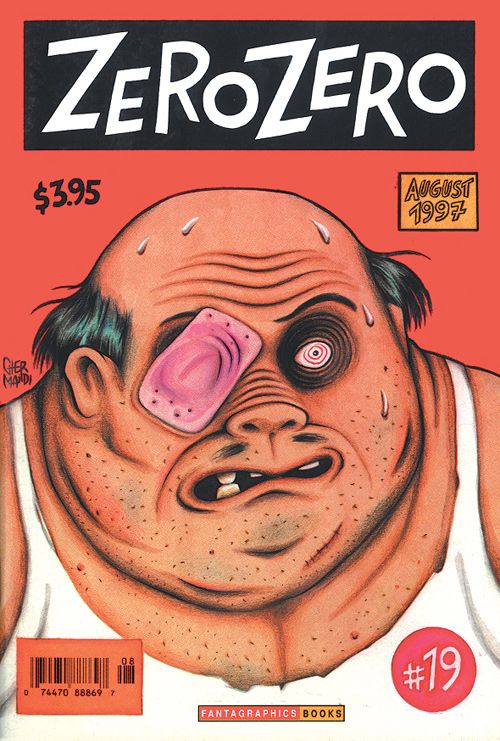

In with these is a plastic comb notebook with a clear cover and photocopied pages of the first several chapters of Pop. 666, then called Suburbia. It only had one chapter in English, the one published by David Mazzuchelli in Rubber Blanket, the rest was not translated. Like the hardbound cartoon books Francesca had sent me, however, the strange and grotesquely beautiful world she drew sucked me in. I really wanted to publish this stuff in Dark Horse Presents. I don't know why it didn't come to pass, maybe I couldn't get anyone else to see what I saw. There is no date on the letter, Francesca could have sent the same packet to Fantagraphics right about then. The timing makes sense. They started serializing the story off and on in their anthology Zero Zero beginning with the 19th issue in the summer of 1997. They eventually printed all 90 pages, but unlike some of the other strips from the magazine, Pop. 666 has never gotten its own collected edition.

I'm not sure who came up with the title Pop. 666, but it calls to mind the title of Jim Thompson's western novel Pop. 1280. Thompson is one of the best of the hardboiled school, having written classic genre pieces like After Dark, My Sweet and The Grifters, inspiring many a modern crime writer and filmmaker. Thompson's book is about a sheriff at odds with his town, the kind of squalid community where all life is a give-and-take proposition. These people are damned by their own evil deeds, they are the future populace of hell. Pop. 666.

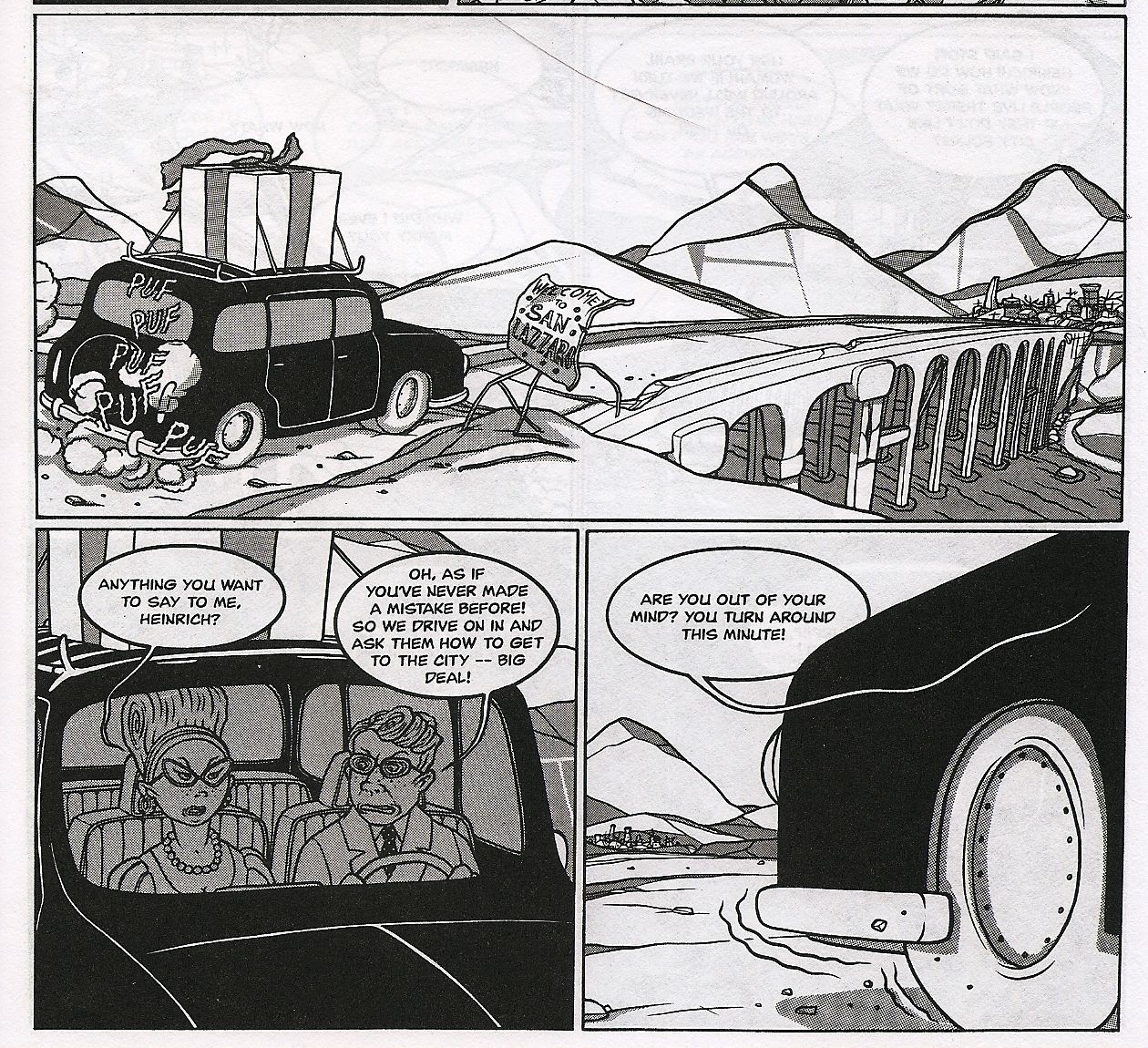

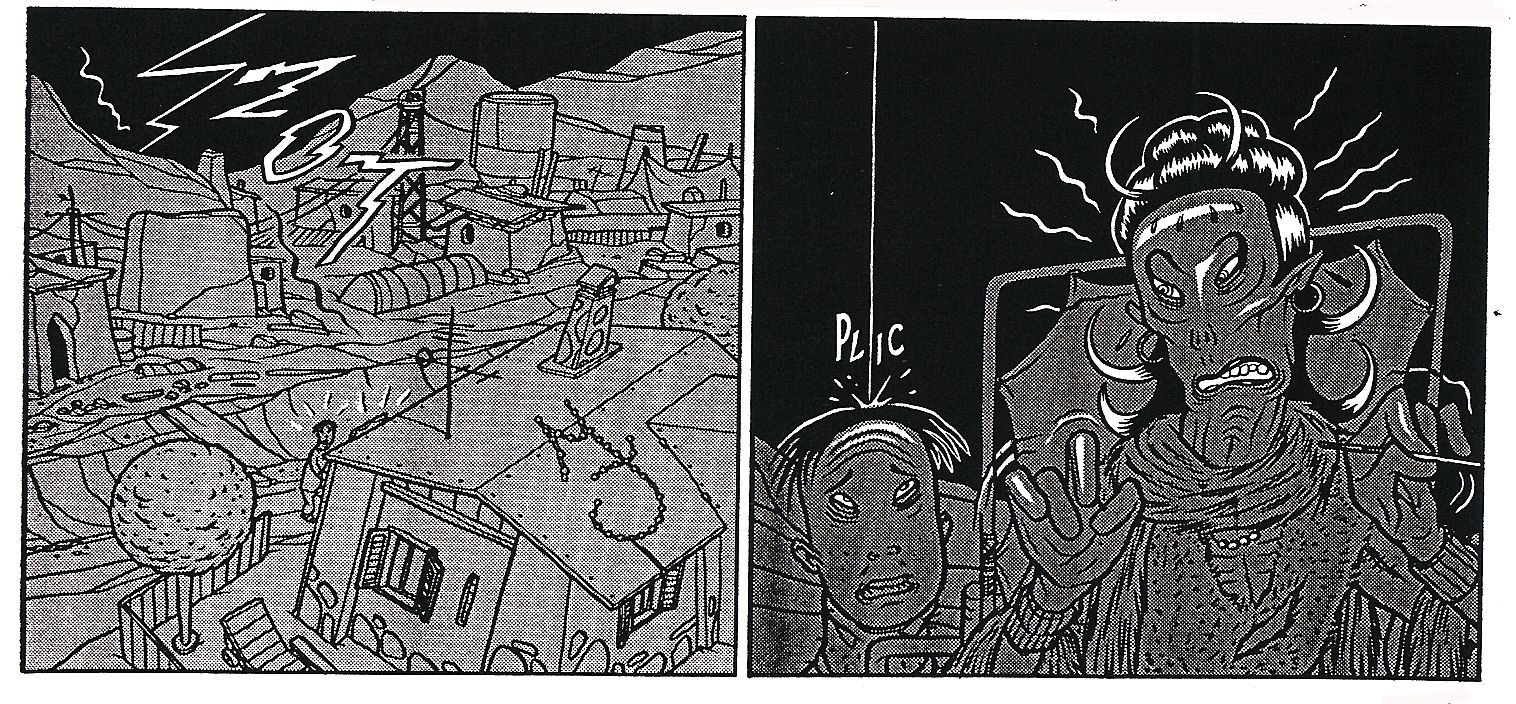

Ghermandi and Semerano's story is set in an unspecified slum village out in the middle of nowhere. As the tragically lost and soon-to-be-dead married couple who accidentally arrive there in the first chapter let us know, you've got to be plenty off the beaten path to land down in this sub-Dante inferno. Despite this being a junkyard society for the homeless, the folks in the area are muscled by a fat, one-eyed lout named Rocco. There may be no landlord, no deeds of ownership, but Rocco collects taxes all the same. He would rule the area completely if not for two things: the sinister Snake Eyes who refuses to pay this sweaty hood tribute and the fading movie star Hilde Historietta. Fear and love, many a villain and many a hero have fallen into the fire because of those two emotions.

All of this is pretty much set up in the first two chapters, and the storytellers take us through a labyrinth of weird twists and creepy scenarios from there. Social workers with a mean streak, mad scientist labs, vain television hosts--all of these get sucked into the overall plot. When life is on the skids, there are those who just lean into it and those who try to drive their way out. Some get run over, some step on the gas. In Pop. 666, fortunes change at moment's notice, and events are never anything short of bizarre.

If Pop. 666 were a movie, it might actually be too bizarre for its own good. No matter how wicked the special effects, the filmmakers would run the risk of making it seem like it's weird for no reason. They'd end up with something like Dan Ackroyd's Nothing but Trouble rather than Jeunet's City of Lost Children or von Trier's The Element of Crime. Comics have always had the benefit of being their own self-contained worlds without having to rely on any fleshy things or real world stumbling blocks to build on. It's all paper and pen, and with a clear vision like Francesca Ghermandi's, the world is complete and need no justification to seem believable. In his profile of the cartoonist, Paul Gravett mentions both Tex Avery and Chester Gould, both of whom provide pointers to Ghermandi's sense of slapstick and monstrous mugs. Her flare for tarnished glitz also reminds me of her fellow Italian, Federico Fellini, whose later cinematic portrayals of the dimming glamour of the performing life may have influenced Hilde Historietta. Maybe some David Lynch, as well? The 1950s monster movie tropes and the strange snouts Ghermandi gives a lot of her characters also recall the skewed work of Charles Burns. Her ink lines are as fluid as Burns', flowing naturally into rounder shapes, avoiding harsh angles. (No surprise, then, that she would invent Pastil, the girl with the aspirin tablet for a head.)

Fantagraphics has been promising Ghermandi's latest book, Grenuord, for a while now. Last explanation I read was that it was taking Kim Thompson longer than expected to translate, and since the third issue was published in 2006, we've been patiently waiting for the rest to be translated and one big book to be released. While this production continues, might I suggest a repackaging of Pop. 666 in the meantime? This weird and creepy sci-fi horror crime comic is a loopy piece of work, and it deserves to be experienced by more readers and might even lead the way to reminding some about Ghermandi in anticipation of Grenuord.

I mean, stranger things have happened. And if they did, it was probably in a Francesca Ghermandi comic.