To all those who have been enjoying this column and wondering where it went, I apologize about the long hiatus. I have no excuses other than it's been a bumpy year. In any event I shall try to keep things proceeding from here on out at a more regular pace. It might not be weekly, but it won't be bimonthly certainly.

Anyway, for the return of Collect This Now, the column wherein I pick long-neglected comics and make a case for them to be reprinted, I've picked the mother of all lost causes. You can pray to St. Anthony all you like but you'll see gold-embossed Miracleman Omnibus with a foreword by both Neil Gaiman and Todd McFarlane before you'll ever set eyes on the trade paperback of this puppy, thanks largely to the Walt Disney company.

Wherefore you ask? What possible reason could the Disney Conglomerate (Inc.) have to prevent this material from ever being printed again? And is it possible that if I click on the link below I will encounter images that are most definitely Not Safe for Work?

Mmmmmmmmm ..... could be.

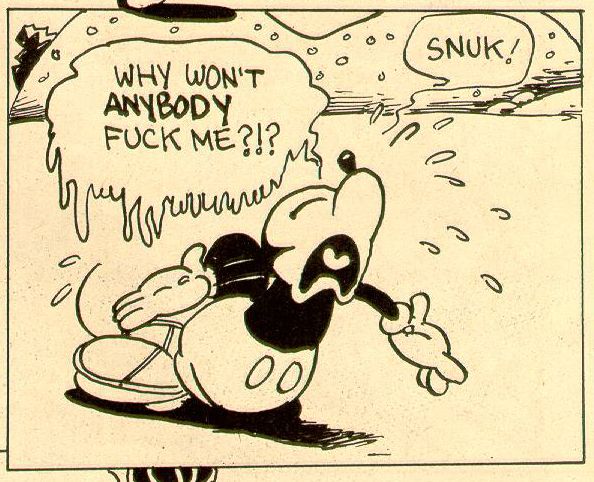

So yeah, there's that.

And yes, we're in smartass, underground, sophomoric, "ha-ha, Mickey Mouse has a penis" territory, but there's a lot more to the story (and the comics themselves) than that.

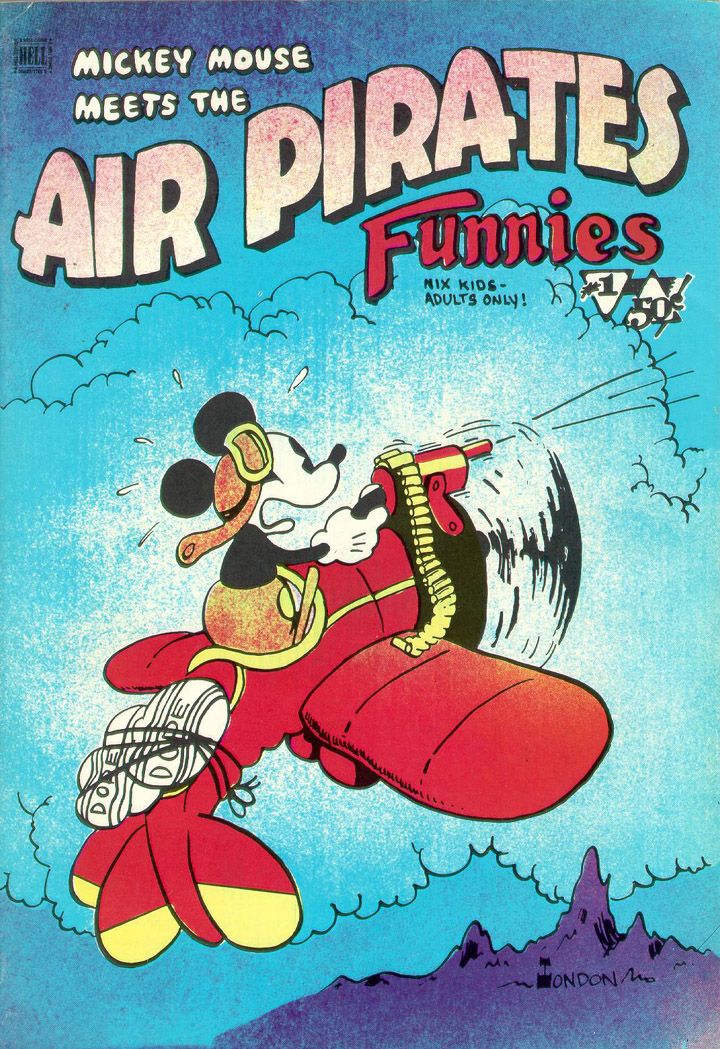

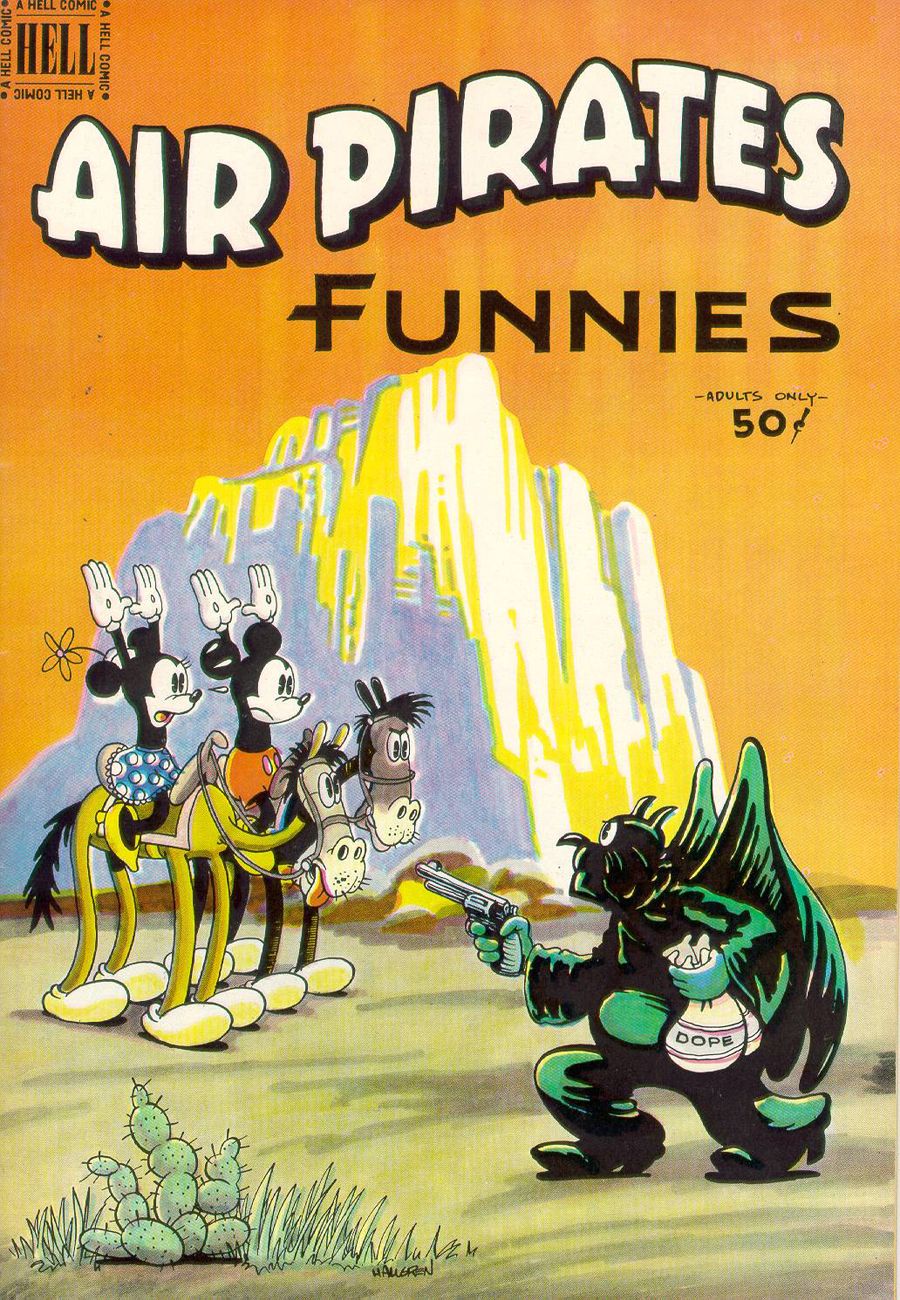

The Air Pirates (yes, it was the name of an actual group of people) were a group of underground cartoonists led by one Dan O'Neill, but also including Shary Flenniken, Bobby London, Gary Hallgren, and Ted Richards. Bound loosely together by a love for old comic strips, the group, encouraged by gadfly O'Neill, decided around 1971 to take on Disney's then-most famous icon. Rather than offer up a over the top, Mad-style parody, a la Mickey Rodent, O'Neill and friends (minus Flenniken, who declined to participate) decided it would be much better -- and antagonize the company that Walt built even more -- if they just went ahead and used the original character instead of calling him Rickey Raus or what have you. Everyone knows who they're making fun of, why even bother pretending?

Perhaps they might have gotten away with it if had it just been one stand-alone issue, but when the second issue came out soon after the first it was clear that O'Neill meant for this to be an ongoing, serialized story, that he was going to try to do his own Mickey Mouse comic independent of Disney, a notion which, naturally, the company didn't exactly take a shine to. It didn't help matters much that O'Neill seemed to be spoiling for a fight, to the point where he had the son of a Disney board member smuggle copies into a board meeting.

I'm not going to delve into the sordid history of the inevitable lawsuit that ensued here except to say that it was extremely lengthy and colorful and remains to this day a seminal case in copyright law. Instead I'm going to attempt, in the short amount of time and space allotted, to talk about why this book should see print again. For those interested in the sordid details I heartily recommend Bob Levin's excellent The Pirates and the Mouse, which goes into much greater detail and insight into the personalities involved than I can here.

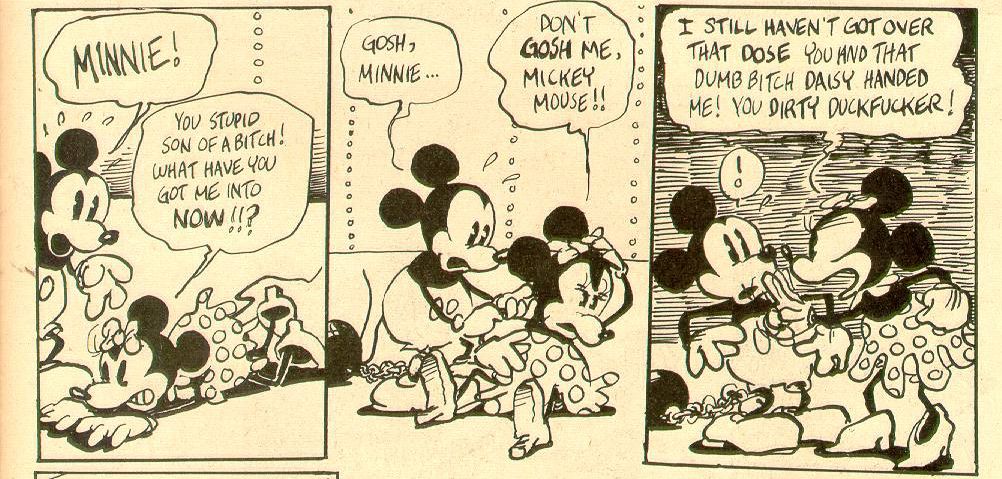

To an extent, the Air Pirates comics suffer from all the sins that clung to underground comics of the '60s and early '70s. They were sexist. They didn't make much narrative sense. And yes, as noted earlier, they indulged in the sort of "x-rated action and drugs fer laughs" stuff that gets tired rather quickly.

But the Pirates' enthusiasm for their material goes beyond the simple desire to irk a bunch of stuffed shirts in a major entertainment company (not that there isn't something to be said for having that as your long-life goal). In addition to their love for the work of folks like Segar and Herriman, the cartoonists were obviously devout fans of Floyd Gottfredson's Mickey newspaper strip that ran a staggering 40-plus years, from 1930 to 1975.

Those strips, at least the early ones, saw Mickey as not some simpering, brainless icon but as a man of action who battled all sorts of nefarious characters like the mysterious Phantom Blot. The Air Pirates comics, sex and drugs aside, feel like an honest attempt to continue in that vein, to show that Mickey doesn't have to solely be a neutered pitchman but can easily become a living, interesting character in a universe that's thrilling and entertaining.

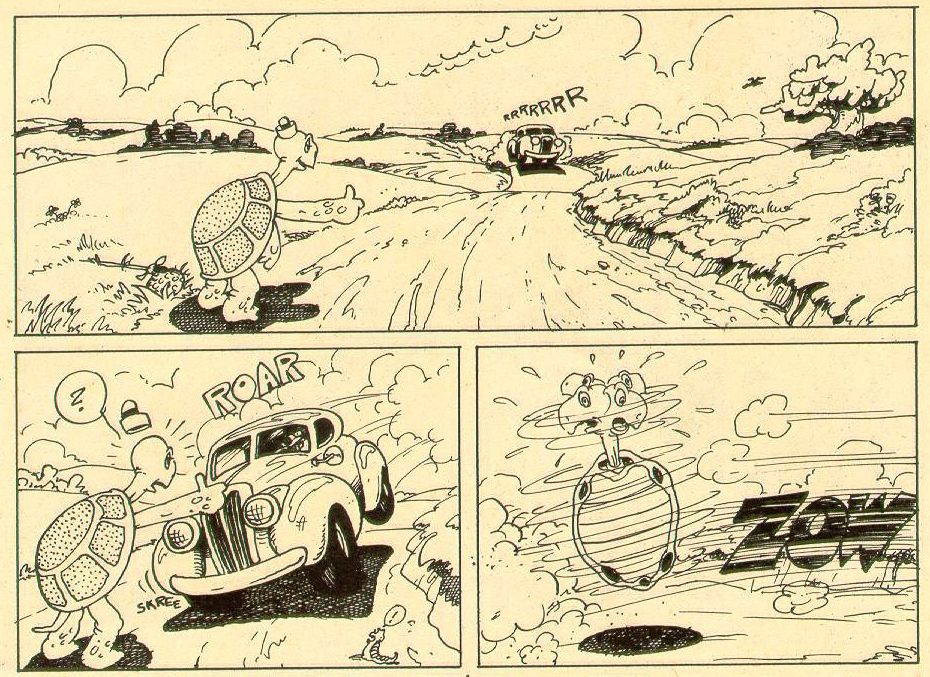

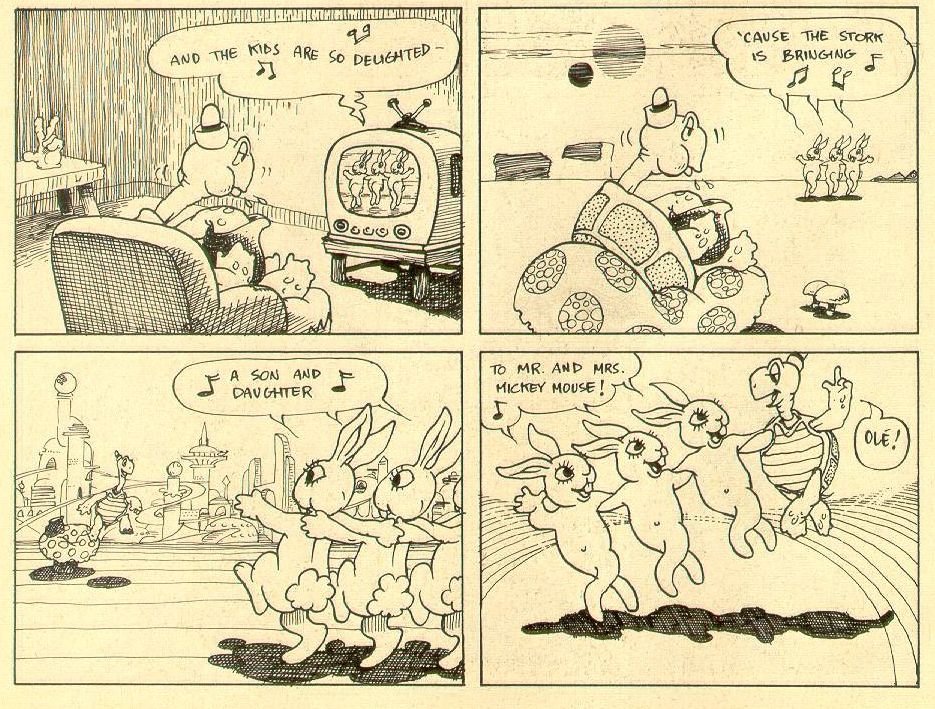

What's more, there's some really fantastic cartooning going on in these comics, particularly from Hallgren, whose Tortoise and the Hare sequences are crammed with detail, invention and a childlike sense of playfulness that many underground comics of the time (at least the ones I've read) severely lacked.

But O'Neill is no slouch either. In addition to his Mouse tale, he provides a "Silly Sympathies" spin-off involving a horny bug who converses with about the nature of Jesus' love (apparently Jesus wants you to be dead and frowns upon masturbation). Despite his slap-dash, rough-hewn style, O'Neill here manages to evoke both Herriman and the old-time look of those early animated cartoons.

In a weird way, these comics are closer in spirit to the original Silly Symphony and Mickey Mouse animated shorts than anything that runs on the Disney Channel today. The Mickey portrayed in cartoons like Plane Crazy was much more of a mischief-maker and closer in spirit to Gottfredson's version than the kid-friendly . The Air Pirates captures that initial. devil-may-care essence extraordinarily well. These comics have a manic verve and spontaneity that I doubt today's Disney could easily reproduce (assuming they were even interested in trying).

Today your best bet to reading any of these comics is to buy Levin's book or track down a bit torrent copy online (and we certainly don't approve of such things around here). It's hard not to see that as a real shame. Ultimately, the Air Pirates comics are simply too historically significant, too outrageous, too weird, too outlandish and too goshdarned good to have them never see print again.