Note: Some images below contain mild nudity that may be NSFW, depending upon where you W.

Blutch, born Christian Hincker, was one of the most influential cartoonists to come out of the French alt-comix scene of the 1990s (although he arguably owes quite a bit to Edmond Baudoin). Blutch's masterful, expressive line, exemplified in works like Peplum and Le Petit Christian, influenced a number of artists both in Europe and here in America, most notably Craig Thompson. Blutch's art was such a strong influence on Thompson while he was working on Blankets that L'Association publisher Christophe Menu derided the work as being too derivative and the supreme example of the co-opting the French small press scene in his book-length essay Plates-bandes.

Very little of Blutch's work has been published in America. To my knowledge only three of his stories have been translated and printed in three anthologies: Two Drawn and Quarterly books and one SPX collection (the 1997 one). He was, however, one of the contributors to the animated film Fear(s) of the Dark, which you can find easily enough on DVD.

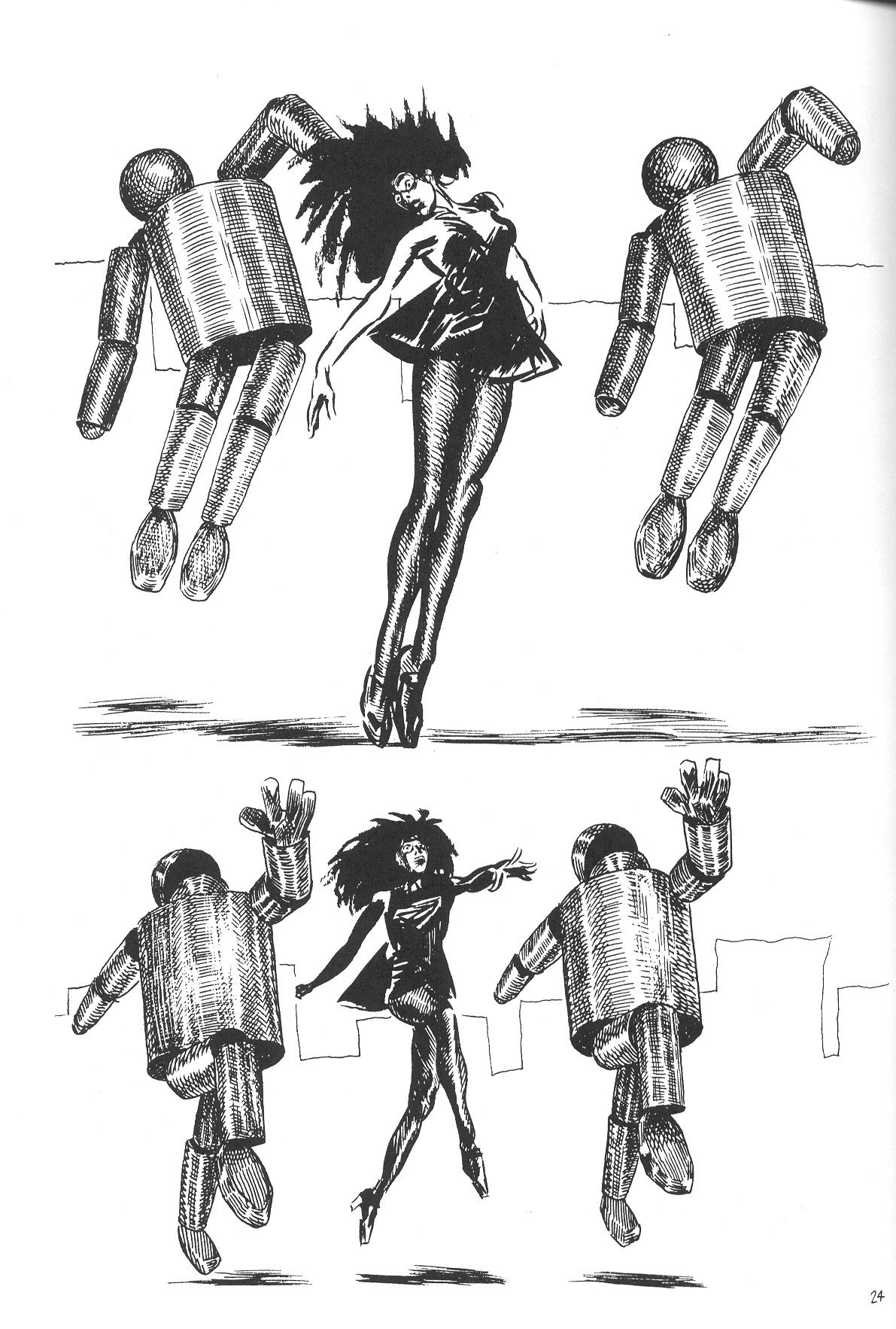

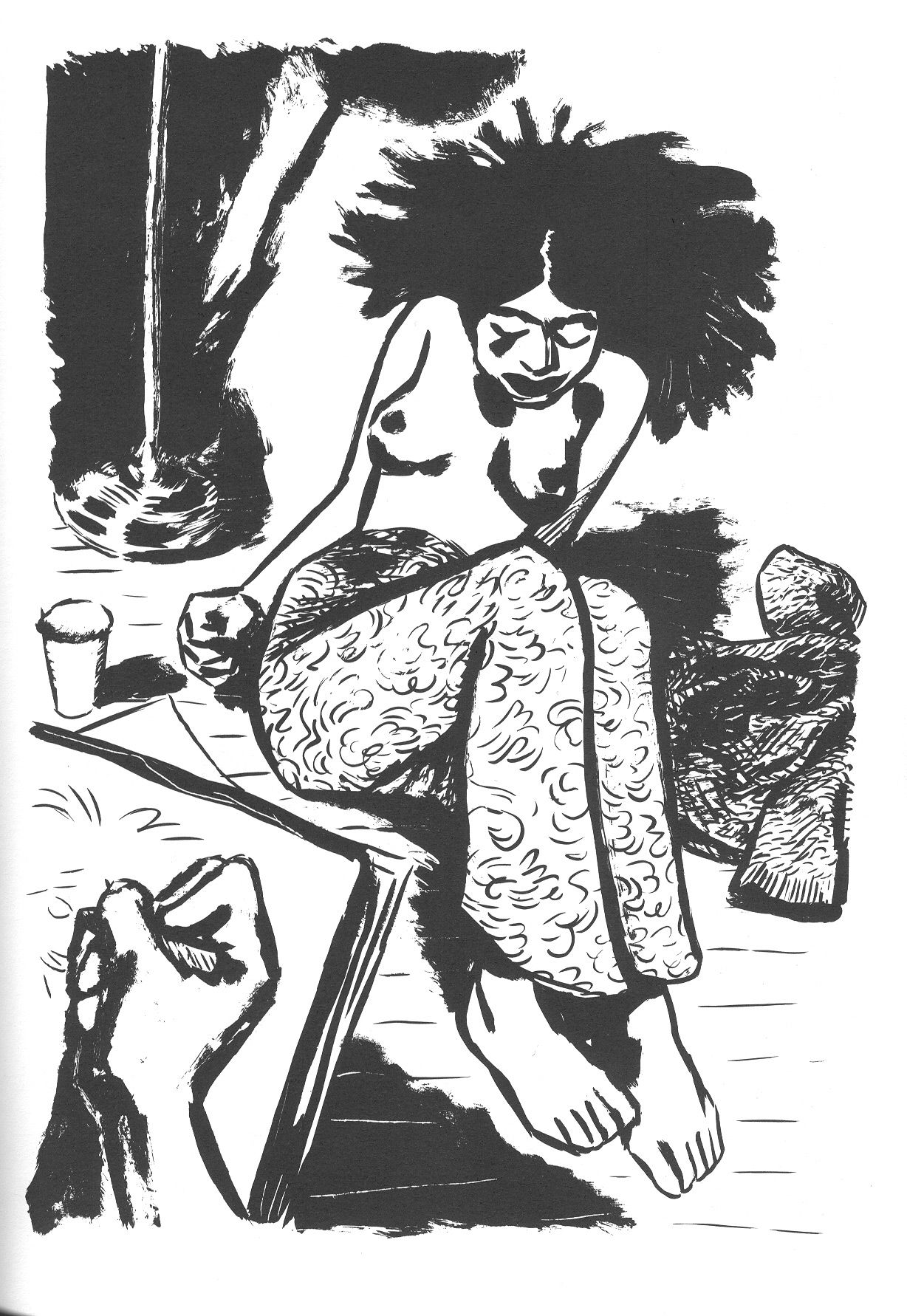

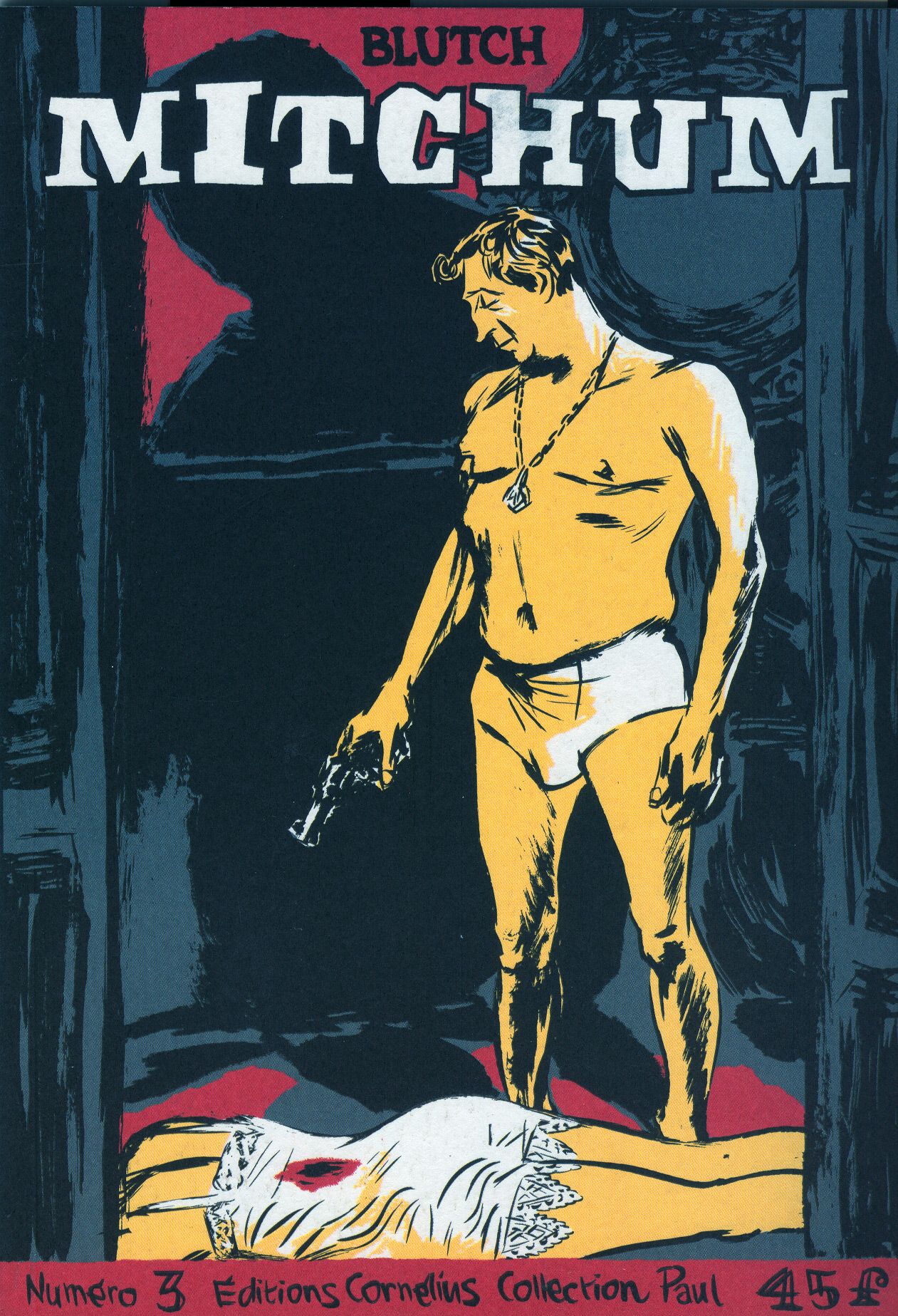

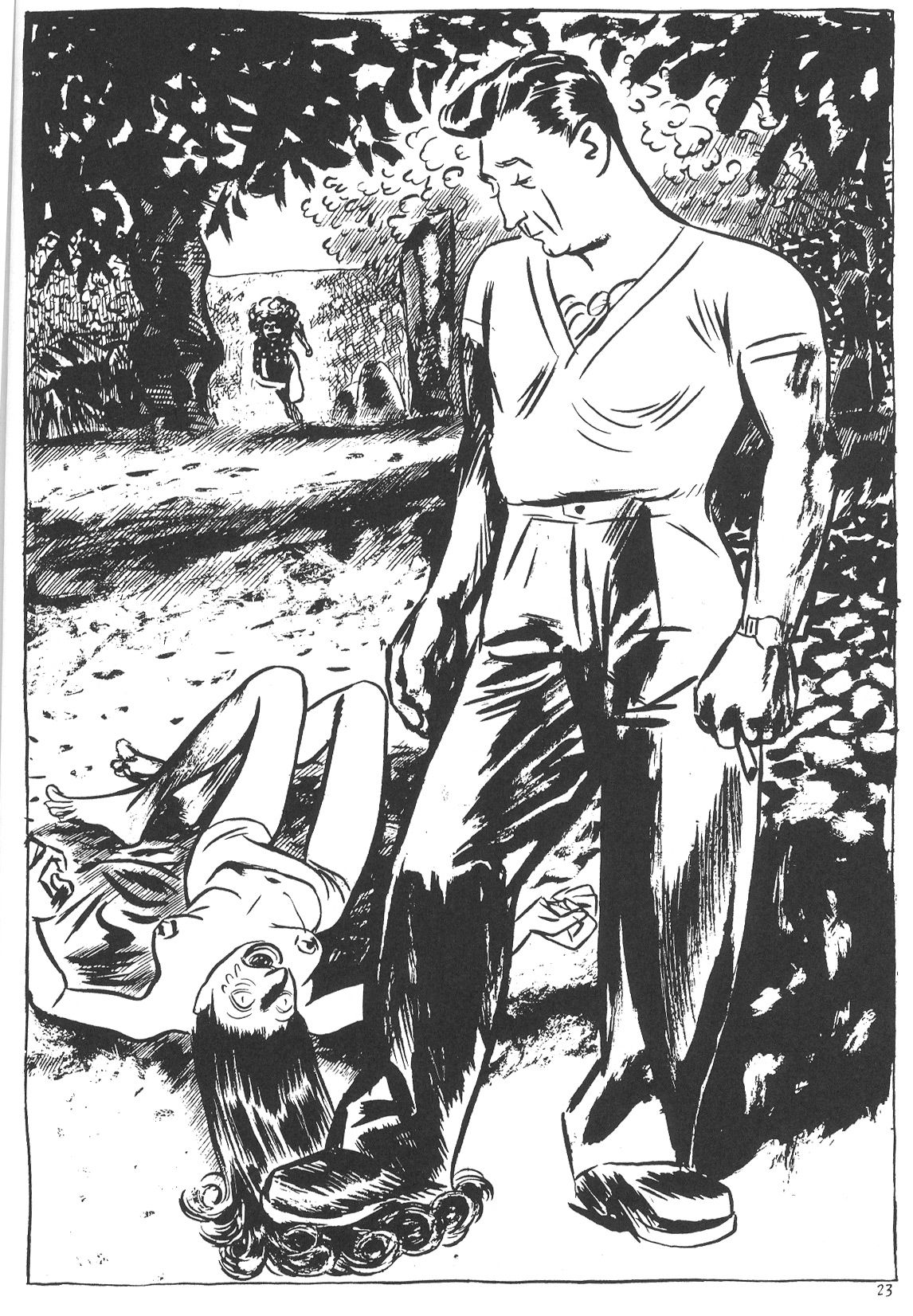

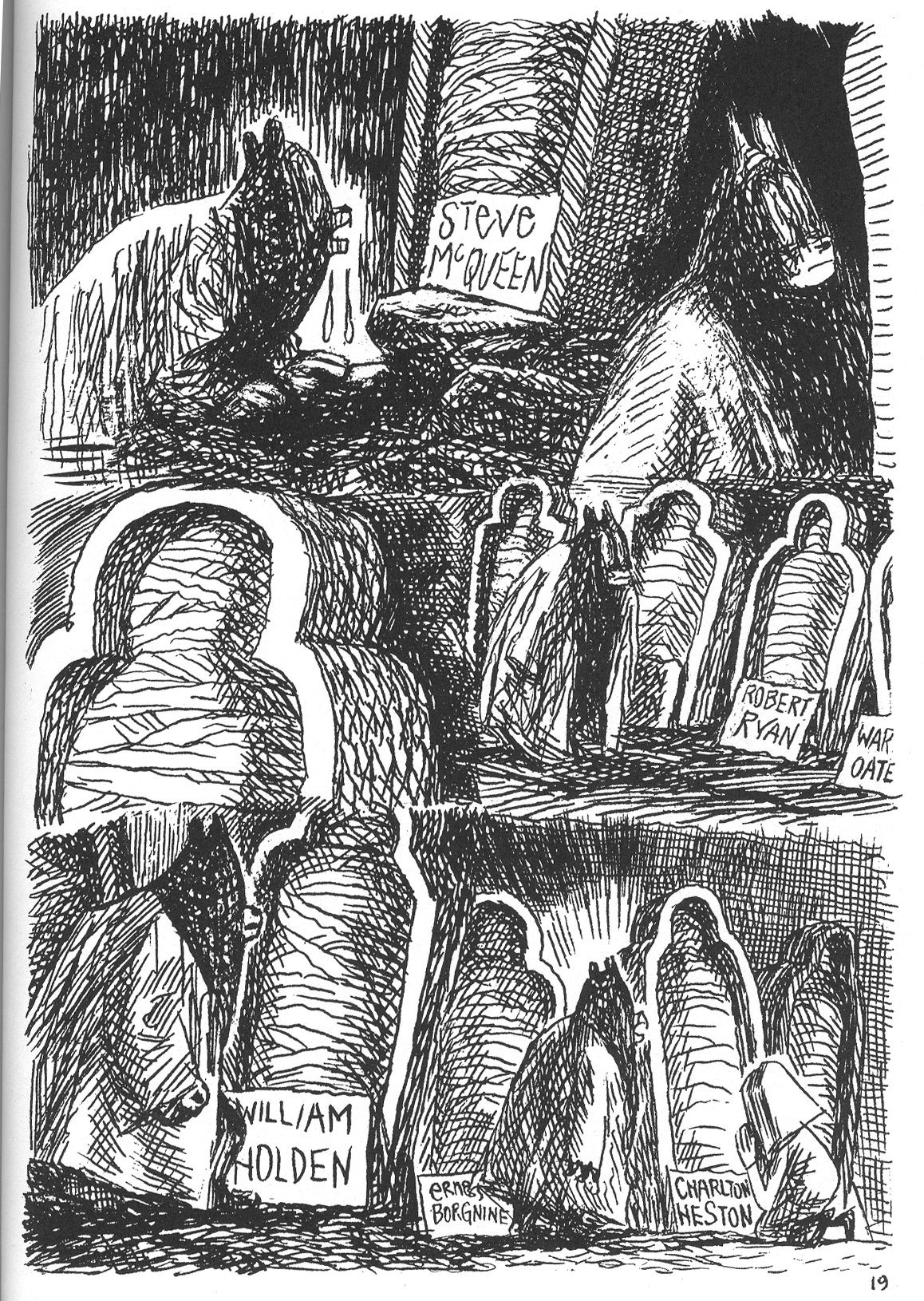

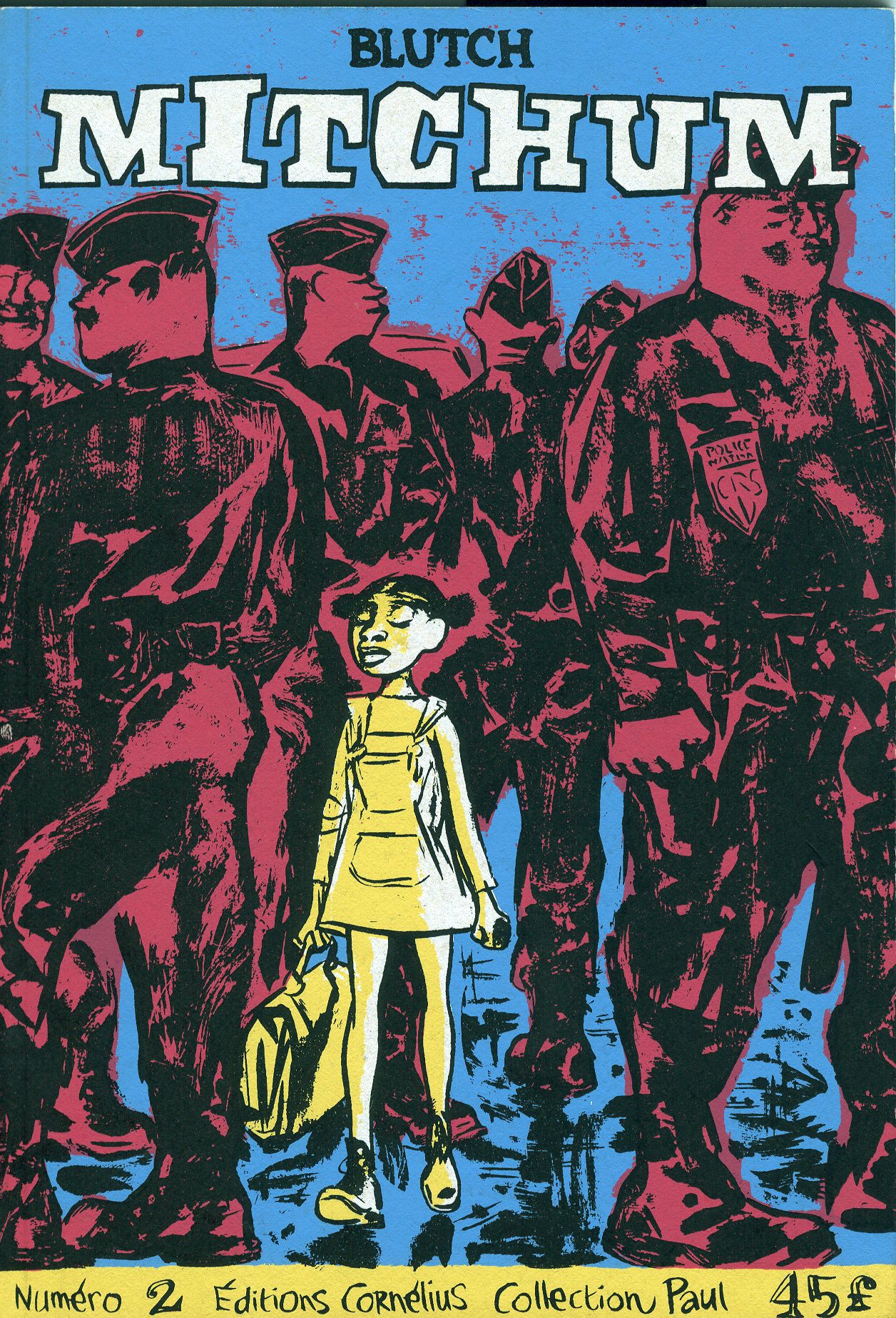

Published between 1996 and 1998 by Cornelius, Mitchum is a collection of five slim, seemingly improvised volumes. Abandoning straight narrative altogether, Blutch instead opts for a haunting, dreamlike reverie here that revolves around issues of sex, race, art, motion (especially dance) and, as the title of the series suggests, Americana. Although somewhat related thematically, there are no reoccurring characters or stories between the volumes and plots are not nearly as important as evoking mood. This is Blutch at his most experimental, expressionist and carefree.

The first volume (and the most straightforward) sets the tone right away with the wordless story of a Pilgrim who ventures out in the wilderness to chop wood, spies upon a young Native American girl bathing, and perhaps (it's never made clear) comes to an untimely end when caught peeping. The following story, Birth of a Nation, is even more explicit with a 17th century young boy, an artist, being coaxed into playing a game of blind man's bluff with slave girls, only to be reprimanded by his father, who then proceeds to have his way with one of the girls while the son embarrassingly returns to his painting. The final image is of the three slaves quietly sewing the American flag: sex, race and art all weighing in on each other to create a society.

The third volume is something of a surreal tour de force, with the appearance of the title's namesake. Here, a pretty African-American policewoman attempts to save a lithe young woman (or man -- his sex changes in the course of the story) from a predatory Robert Mitchum, who moves between various ages and stages in his career from panel to panel -- a weak but menacing old man here, a robust actor in his prime there. There's also an equally nefarious, spider-like Jimmy Stewart thrown in for good measure.

Blutch is clearly playing off American cinematic images of femininity and masculinity here -- the female cop, for example, bears more than a passing resemblance to Pam Grier. But there's no sense Blutch is attempting to make any overreaching point here. There's no easily discernible, grandiloquent statement on the nature of Western sexual mores or the America's cultural influence abroad. Indeed, Blutch seems to be exploring his own feelings and attitudes toward these issues as much as he is forcing the reader to consider them.

And it's all done with that thick, rough, beautiful line. It's perhaps overstating the obvious to say that Blutch's art is extraordinary. Heavily cross-hatched, even blotchy at times, Blutch's images refuse to stay still. Everything in Mitchum is constantly in motion. Even his scenic landscapes throb and pulse with vitality and power.

A criticism I've heard more than once against Blutch is that while he remains an incredibly expressive and facile artist, he's a bit of a shallow storyteller. I haven't read any of his other non-English work (my French is abysmal) so I can't really comment on that except to say that the stories contained in Mitchum are anything but shallow. On the contrary, they are rich, unsettling, evocative tales that, despite their experimental nature, leave an indelible impression on the reader.

Considering how influential he's been for certain American cartoonists (I believe Jessica Abel and Matt Madden are also fans), it seems odd that no one has made an attempt to bring more of Blutch's work to American shores. Mitchum seems like an obvious choice. Being mostly wordless, there's little need for a translator for one thing. But more to the point it's exemplary, hallucinatory, spellbinding material. Mitchum is a comic I never get tired of pulling off the shelves and re-reading time and again. I'm betting other American comic readers will feel the same way.

For more on Mitchum, I direct you to this essay.