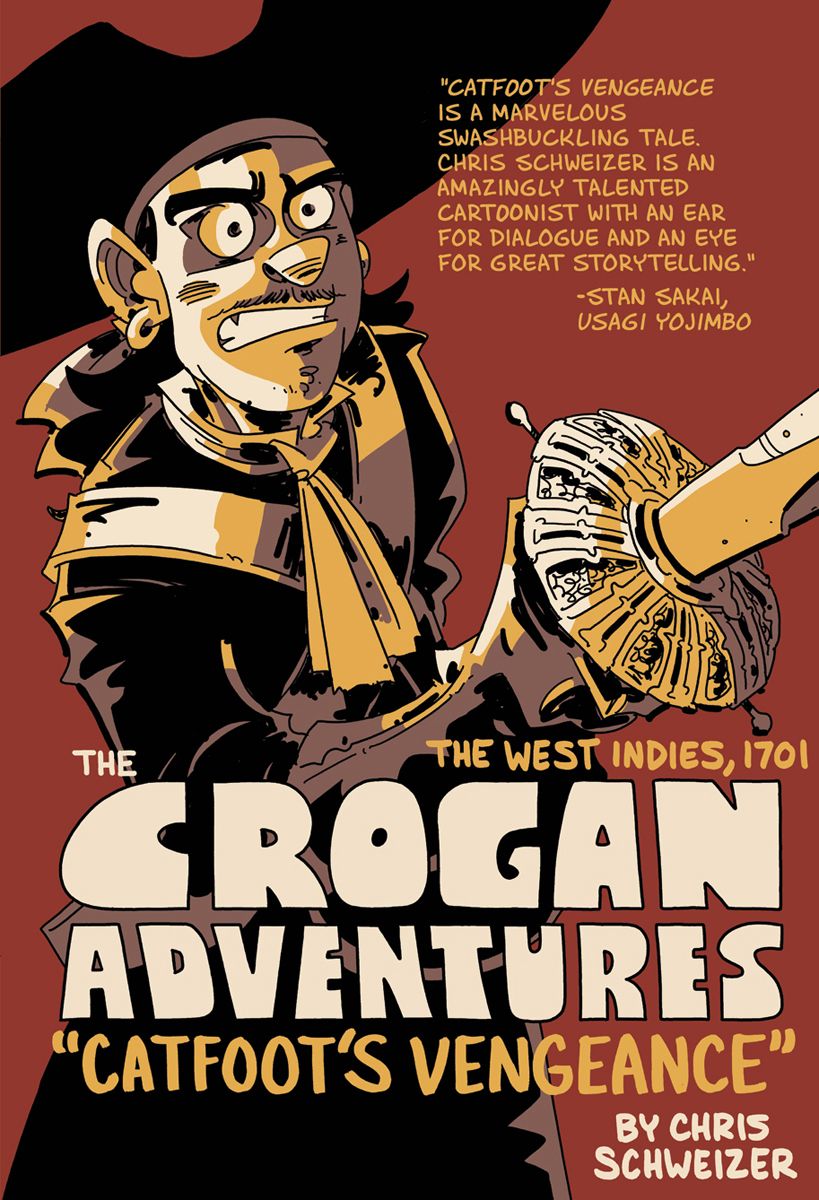

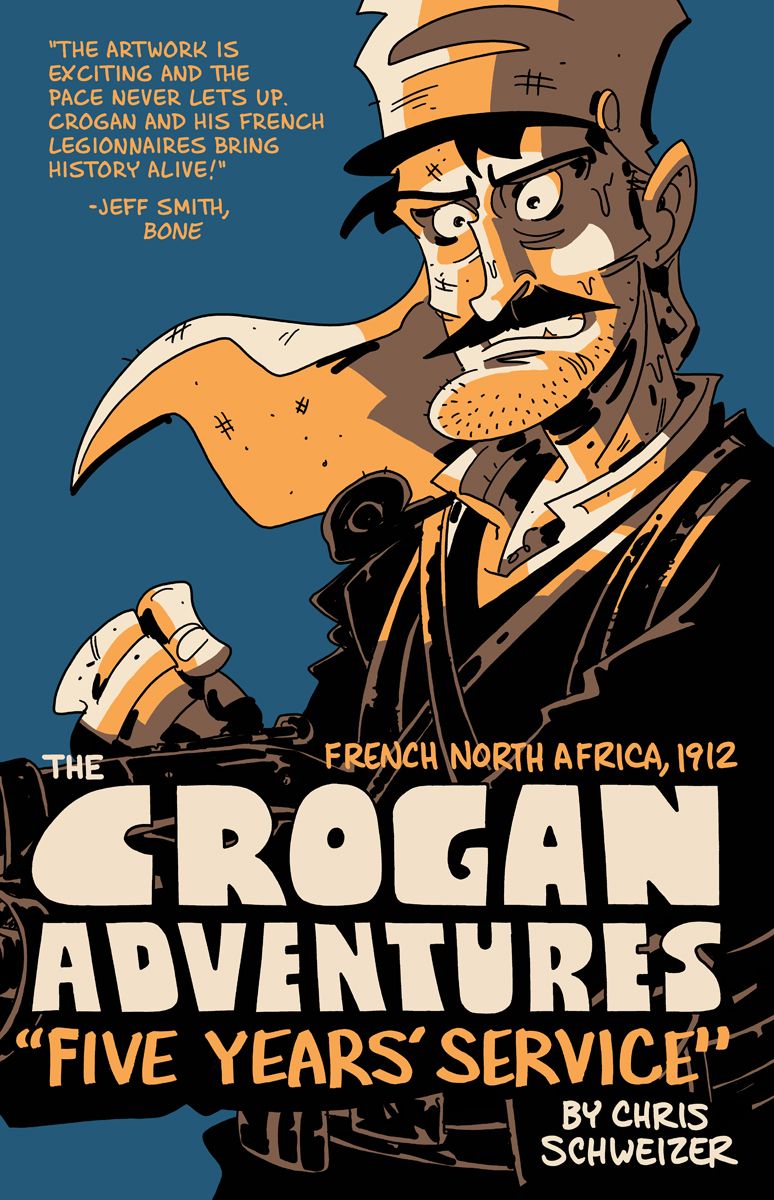

It's difficult to say why I enjoy interviewing Chris Schweizer so much, but it may be because he's always looking to improve his craft. And Oni Press' new editions of his Crogan Adventures series, which are in full color due to the inspiration of Brian Hurrt and Matt Kindt, are only the tip of the iceberg.

Schweizer took some time to talk with me not only about the move to color, but also the expansion of the Crogan family tree to include women, his collaborators, and whether the former SCAD instructor might some day return to teaching.

Tim O'Shea: How flattered were Brian and Matt that they indirectly prompted your decision to switch to color with Crogan?

Chris Schweizer: Yeah, I talk about their role in this a bit in the foreword to Catfoot’s Vengeance, where I explain the reasons for going to color. I wouldn’t really call it “indirectly.” They were the catalyst behind my decision to work in color on everything (if you can call the direction that one’s work takes a decision; I feel like artists have very little say in the matter -- artists can hamper their own evolution but can’t really steer it), which ended up requiring revisiting these earlier books to make them consistent with the ones on which I’m currently working. Their influence over that direction couldn’t be more overt.

As to their reaction, I’m not sure they’re fully aware of the role they played, though I expect I’ve told them. Surely each of them has influenced enough artists that it’s no longer a novelty experience.

When did you realize the family tree needed to have more than male branches?

When I first conceived the series, I had an enthusiasm for history but very little knowledge of it (I’m still no historian, but I have a much better grasp than I used to). I knew that I liked specific historical periods in fiction, and I crafted the family tree (and the series) to highlight them: Westerns, pirate swashbucklers, flying ace stories. The examples of these stories with which I were familiar all revolved around men, and I thought of the series as a kind of “boys’ own” adventure series, similar to some of the stuff I grew up reading and watching, and that was the justification that most folks accepted for having just males in the tree, that it wasn’t a tree so much as an advertisement for future books, books demographically aimed at boys. I had logistical concerns, too. What if there was a romantic plot? Would knowledge of the outcome ruin the story? That sort of thing.

Upon this book’s initial release five years ago, I was invited to speak at the Texas Library Association annual conference, and spent some time with student participants, a large group of San Antonio middle-schoolers that had come out for the event. I was doing sketches for them, and they were looking through their copies of Vengeance, asking for sketches of different characters, some from the book, some from the tree endpapers. Some of the girls, warily, asked if there were any girl characters that I could draw. And I felt like dirt. I’d never reflected on the impact that not finding any girl characters in the endpapers (or in the stories) would have on girl readers, how it might make it feel that the book isn’t for them. I know that sounds ridiculous, that it hadn’t occurred to me, but it hadn’t.

I also had a real fear of writing women characters. I had a professor in college who opined that a man couldn’t write good female characters, that they would always ring of falseness, and that terrified me, I’d rather avoid it all together than do it wrong. It also created a dichotomy for me, this idea that I’d need to treat male and female characters differently, which is the root of the problem. You treat all characters differently from each other, there’s absolutely no reason to approach writing one gender different from the way you’d approach writing the other, it all comes down to the context of the individual characters. That’s simplifying things somewhat, but it does hold true, and it is liberating, artistically.

Anyway, Five Years’ Service [published as Crogan’s March in 2010] was done, or close to done, while I was thinking about this at the conference, but I resolved that in future books I would never not have adventure-y lady characters. But I was worried, to some degree, about how much I could do without damaging historical accuracy. My thought was, well, I can’t have, say, a lady pilot in World War I, because if there had been one historically then that would have changed the course of aviation so far as women's roles in it were concerned. But I set out to study, to see what I could find about each era.

This was one of the biggest punches in the face I’ve ever had, so far as worldviews go. While I could read dozens of history books about World War I or Aviation in it, the only time women might be mentioned is in the popular gender-appropriate role of nurses, etc. But once I started researching women SPECIFICALLY, I found tons of stuff. Women flyers who attempted to start ladies’ air combat units, flying ambulance services, that sort of thing, but were banned from continuing or enacting these things due to their gender. Women who fought openly as women in regular Army units during the U.S. Civil War, the U.S. Indian Wars, the French Revolution, the Mexican Revolution. So many examples, and aside from the famous pirates Anne Bonny and Mary Read, almost none making their way into the “overview” texts on any given historical subject. I really can’t stress enough how flabbergasted I was at this.

So once everything I thought I knew about gender roles in history got upended (and around this time I started looking into the history of different races throughout western history, with much the same outcome), I started trying to figure out the best way by which to work this into the series.

It’s tricky, and I made the same mistake that I think a lot of people who come to this point make. You’re so surprised that this aspect of history has been, to your eyes, at least, unexamined, that you make stories ABOUT how it’s unexamined. I did this with the Free Comic Book Day story from a few years ago, “The Black Brigade,” about an all-black commando unit during the American Revolution. I was so aghast that I had done six months of hard research on the era and never even stumbled on a footnote about it (or almost anything on the other black Loyalist soldiers), that my story was simply a reflection of my shock and discovering their existence, and it was more about the novelty of it than it was straight adventure. I had a student who mentioned to me that he’d never read a book about a black kid when he was young where the plot wasn’t about being black, and here I’d done that same sort of thing with this story. I’m pleased at its technical execution, but that aspect of it really bothers me, it would be a much different story were I to do it now. But that’s one of the reasons to do shorts, to help you work through things. Anyway, it’s helped me focus on the adventure side of things in future stories rather than the social novelty, which wasn’t a social novelty to the participants, it was just life.

So it took me a few years to find historical examples of women in these different roles in the different eras of history, but I wanted to do so because I wanted to have ammunition should I be accused of warping history for the sake of trying to appeal to current market trends, that sort of thing. Pretty much all of the women in the tree spring from an existing historical figure or spring from a composite of multiple figures, except the cartographer. I couldn’t find examples of women cartographers in the sixteenth century but there are enough women who aided their fathers, husbands, brothers in their crafts and excelled that I thought it entirely plausible for this character to arrive at her profession through that sort of official channel. Anyway, I’ve been wanting to do the whole tree, all the progenitors, since shortly after the first book came out, but it’s taken a few years of research to do it the way that I wanted to do it.

What prompted you to team with Eric Newsom on the lettering?

I’d been toying with the idea of creating a font of my hand-lettering for a while, because, although I like hand-lettering, it was adding an hour and a half to every page, time that I thought would be better spent on other aspects of the work. I mentioned this online, and Eric told me that he had experience with font creation. I knew that Eric had worked with other comics folks in the past, and his role with Lady Sabre, and I also knew that he was aware of how nitpicky I was regarding the books, that he wouldn’t be miffed at me wanting to take multiple passes at everything. I also like Eric a lot, which was a factor.

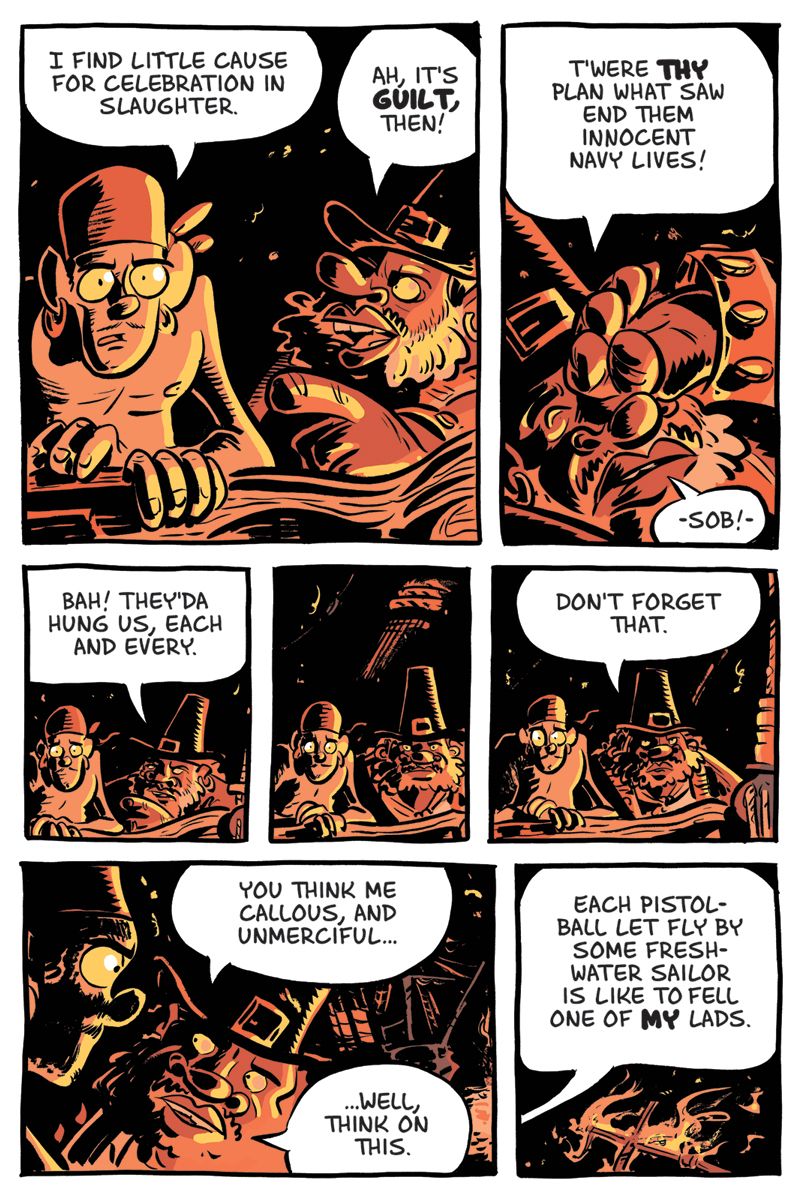

I still use a mix of hand and digital lettering, even with the font. Yelling, whispering, that’s usually done by hand. I still draw the balloons. And as good as Eric made the font, and it’s a treasure, I still tweak a lot of it, manually adjusting the kerning and the leading on different letters or words in almost every balloon. I treat it the way that I did hand-lettering, and so it doesn’t feel too different, it’s just faster, and I have more confidence in the page looking professional, and its legibility.

What is it about Joey Weiser and Michele Chidester's coloring approach that made them the right fit for The Crogan Adventures?

They’re a lot bolder with their color decisions than I am. They use a lot of heavy saturation, a lot of vibrant local color, a wide value range, all things that I’m very hesitant to do. But I felt like Catfoot’s Vengeance needed that bombasity. So that was the first factor.

The second was that we’re friends, AND that they spend most of their time on their own projects. Michelle paints, Joey makes Mermin, they know what it’s like to invest oneself entirely in a project, to have a clear idea as to how you want that project to come together. Whoever I worked with, it was clear from the onset that I was going to be making a lot of changes to the colors that they delivered. Pacing, mood, historical accuracy, directing focus, these are all things over which I wanted to have a lot of control, and I wanted to work with folks who understood and encouraged that. Any changes that I made to a colorist’s work might be seen as a judgment on their decisions, on their art, and I wanted to work with people that I knew well enough to know that they wouldn’t feel that way. Because that isn’t where the changes sprung from. They sprung from me having very specific ideas as to how I wanted each scene to play out. And I wanted Joey and Michelle’s work, specifically, as the foundation for those changes. They would bring things to the page (a sky color, a value, etc) that I never would’ve thought of on my own. My color conservatism, my inclination towards uniformly lighter values, I subscribe to these principles for a reason, but they can also lead to boring, washed-out pages. Joey and Michelle have such punch, and the marriage of our sensibilities is something that I’m quite happy with.

Given how clear a creative vision you always have, I was surprised to learn you had a co-designer on this book. What drew you to collaborate with Keith Wood on the design?

Honestly, if I could have a collaborator at every stage of development, I would. I have a lot of skills and no expertise, and working with an expert on any given component would help the overall work, I’m sure. Keith is a brilliant designer (his work on The Sixth Gun is still some of my favorite comics design work of the last few years), and though I knew what I wanted the book, and series, to look like, it was invaluable relying on him to help me see that through. He handled all of the technical aspects (layout, etc.), and we collaborated on things like what would be on which page, all of that sort of thing. He let me handle the brunt of the cover and made a few suggestions and tweaks that improved my initial concept considerably. The series title, for instance, was a color in my pass, and the volume title white, he suggested switching the two, and it pops far more. He handled things like the spot gloss, all of that.

As with Joey and Michelle, the biggest draw to working with Keith was his willingness to let me be the big ego on the project. When I collaborate on a project from the start, there’s a lot of back-and-forth, give-and-take amongst the participants, but The Crogan Adventures are books that I think of as wholly mine, and so the collaboration is less a collaboration than it is me working with other people to see my “creative vision,” as you put it, executed. And that seems like such a stuck-up thing, such a jerky approach to take, that I’m hesitant to ever work with anyone on any aspect of it, because I don’t like to act like that. Working with friends who know me as other than a creative tyrant makes it possible for me to act like a creative tyrant.

You are a constantly evolving creator. Given the time/development difference between when you first put this out and its re-release: how has the passage of years impacted the way you view this era of your work?

It’s weird, immediately after I finish something I no longer feel like I made it, it feels like it’s just something that exists, that was published, whose execution I happen to know a lot about, but that’s it. I guess because once it’s published it no longer belongs to me, it belongs to the readers. Their responses, what they take from it, that outweighs my intentions, my motives. That might be the reason.

Were I to do the book today, I doubt it would have a single thing in common with the existing story, except maybe the cast (which I would’ve added to). But that’s a good thing. It’s a lean swashbuckler. It’s built around a series of cliffhangers, there are good sequences, I’m not hitting anyone over the head with historical anecdotes, it’s a stripped-down exercise in storytelling above everything else, and I’m proud of that. It lacks pretension, and is better for it.

I dwelt on what I didn’t like with the book, or my approach to it, in crafting its successors, so I wasn’t really surprised by anything. The most problematic part was the lettering, which we addressed, and otherwise I feel like I can stand by it. Some sequences are better than I remembered them being, or at least I can see now that they worked, removed from the making of them.

Looking at this volume with all of its improvements, do you have three or so story beats you appreciate on a whole different level than you might have as a younger creator?

I feel like I’m usually pretty conscious with what I do, try to find the narrative or thematic meaning in a moment, so I wasn’t really surprised by anything. I’m still most proud of the parts I was most proud of when I made it. The dialogue feels period, which is something I’m usually critical about when reading historical comics/watching historical movies. I feel like the ship-burning scene effectively conveys the social and strategic necessity of brutality on the part of the pirates in a way that lets you understand where they’re coming from. I think I wrote it for that reason, but it’s far more succinct and effective.

The new trade dress emphasizes the series more than the individual volumes, what brought about this change? Does it make The Crogan Adventures more accessible for librarians and patrons?

This was something that James [Lucas Jones, Oni's editor-in-chief] and I really, really wrestled with. We went back and forth as to whether we should highlight the series or the individual volumes, which are crafted to be read in any order, as standalones. But the truth of the matter is that if it’s a series, people are going to treat it as a series, and so we decided to push that aspect of it.

I like having a little more freedom with the titles, not being beholden to “Crogan’s this-or-that.” What was once called Crogan’s March is now called Five Years’ Service, Crogan’s Loyalty is just Loyalty. I wanted to call Catfoot’s Vengeance “On the Account,” a term for turning pirate, but James, rightly, was concerned that if the book had a dramatically different title from its original edition that people might buy it thinking it was something entirely knew, and be miffed when they realized it was a story they’d read. Catfoot’s Vengeance is close enough Crogan’s Vengeance that probably anyone who knew the old version would pause before buying the new, make a conscious decision instead of an erroneous one.

In issuing the new edition why did you stick with the original 2008 “about the author” pic?

I think it’s important to remember that works, even ones that are part of a series, are a product of an author at a particular stage in his or her life. I made Catfoot’s Vengeance when I was 27, so to me it seemed most appropriate to include a picture of me from that age. I’ve done the same on other books upon their initial release, and could see no reason to change it on reissue. When I’m 80, God willing, the book I make that year will have a picture of me at age 80.

How critical is your wife Liz to your overall career success?

She’s essential. Regular human stuff (health insurance, groceries, etc.) takes me an inordinate amount of time, and I do it all wrong anyway. She handles all of the family stuff. I mean, I’ll run errands for us and things like that, but she manages it all, our calendar, our finances, all of that. That in itself is a huge help, because it frees me up to work. She’s incredibly supportive, which goes a long way, emotionally. Having your partner on board with your goals is really the only way that they can happen, I think.

Over the past year or so she’s been assisting me in a more practical arena, work-wise. She runs my online store, so things actually get shipped out in a reasonable space of time, original art and prints and that sort of thing, and I’ve started teaching her how to color digitally. I’m coloring my other series, The Creeps, and she’s been going in and doing local color flats on the main and primary supporting characters, coloring them according to the model sheet. This is saving me a ton of time, as I can just add cell shading when needed, tweak according to the demands of a given scene, and concentrate my coloring attention on the backgrounds, which are a little looser, more gestural. It’s making an otherwise impossible deadline doable. Like this book now, I have five weeks in which to ink and color 122 pages if I want to have it done before the end of middle of May, and I have to, because I won’t be able to work on the boat, and I won’t be back home until July. Artists’ spouses used to spot blacks, I feel like local color flatting is the new spotting blacks for spouses.

Creatively, do you find there are less distractions vying for your attention living in Kentucky versus your days in Atlanta?

When my attention is diverted from something on which I should be working, it’s almost always by another project, so location has little to do with that. I’ve always been good at limiting the time I spend doing non-work stuff and, living in a rural area now makes it harder to concentrate, because instead of taking ten minutes to walk down the street to drop something off at the printer, or drop by a bookstore, or something like that, I’d have to drive to Evansville or Nashville, make a day of it instead of a lunch break. So I almost never leave the house anymore because I can’t do so for a brief outing, and I haven’t time for anything other than brief.

Is there ever a time you might teach again? Do you still mentor some aspiring creators even though you are no longer a professor?

There’s no way to know what the future will hold and what my priorities will be, so I’d never write anything off, but I have no plans in the foreseeable future to teach in an official capacity. Which is hard, because I miss it a lot, almost every aspect of it. But I’m able to produce the work I’ve wanted to produce at the pace that I’d wanted to produce it, and that’s extremely satisfying. I have the freedom to pursue multiple projects, I have more time for my family. As much as I would like to be able to balance work, family, and teaching, history has shown that I can really only manage two, and I’m happy with the two that I’ve chosen.

If my schedule permitted, I’d like to someday do something along the lines of what Svetlana Chmakova, Craig Thompson and Paul Pope did in New Smyrna, an extended live-in workshop with a select group of accepted students. There are no plans for that sort of thing any time soon, but it’s the most likely avenue by which I could do any teaching outside of occasional weekend guest lectures at colleges.