On Free Comic Book Day (May 7), First Second Books promotes its new "Science Comics" imprint. Under the tagline "Get to Know Your Universe," the line of graphic novels will examine topics including Coral Reefs, Volcanoes, Bats, the Solar System, and Dinosaurs.

In the FCBD introduction to the initiative, creators Maris Wicks and Jon Chad have each drawn a short comic introducing some of the issues covered in their books. The offerings offer a sense of the tone and approach they and the publisher are taking in trying to make science fun.

Wicks' book, "Coral Reefs: Cities of the Ocean," is available in stores now, while Jon Chad's book, "Volcanoes: Fire and Life," comes out this fall. We spoke with both cartoonists about their projects, and the unique rewards and challenges that come from marrying their loves of science and sequential art.

CBR News: "Coral Reefs" and "Volcanos" are large topics. How do you start with those and turn the idea into comics?

Maris Wicks: First Second actually asked me to specifically do a book on Coral Reefs! I had been an educator at the New England Aquarium for 5 years and was itching to do some sort of comics project related to the ocean, but the topic of "oceans" is so broad, I didn't know where to start! When the "Science Comics" series was in its initial phase, Calista Brill -- one of my First Second editors -- had the idea for a coral reef-themed graphic novel. I used coral reefs as a platform to launch into a broader topic that involved global ocean health, because you can't have coral reefs without the ocean, and you can't have a healthy ocean without coral reefs!

Jon Chad: The first thing I did was, I thought about what people's default thoughts on volcanoes are, and that was my starting point. I think a lot of peoples' entry point to volcanoes is one of fear. They think of Super Mario lava pits, eruptions that overrun homes, the evil mountain where Sauron forged the One Ring, etc. I'm not going to deny that volcanoes are dangerous, but I realized that I wanted my primary goal to be to change a reader's perception of a volcano as a purely destructive force, to a force that promotes life and change all over the Earth.

After I honed in on that as the goal, it was just a question of, what qualities of volcanoes do people not know about, and how can I relay that information? How can I balance the reality of hot, destructive magma with its potential for good?

Maris, you use a fish to narrate and guide the book, and Jon, you present a group of people in the far future as your framing device. Why did you decide that you needed to convey the information in this way, and how did you settle on these approaches?

Wicks: Short answer: I think the idea of a talking fish is funny. Long answer: A lot of the material in "Coral Reefs" is on the scientifically-dense side. I think that having an engaging -- and often silly -- narrator, as well as using the medium of comics to help explain complex ideas like the water cycle and climate change, helps to make the information on the book more accessible.

Chad: I wanted to provide a cast of characters that would be prone to being in awe of a volcano's tremendous power and capacity for good. The reader would be able to share in the characters' excitement at learning facts. Setting the story in bleak, frozen future created characters that valued heat and life. The visual of the frigid landscape contrasted with the imagery of volcanoes, making each eruption leap off the page. Also, I get very excited in toeing the line between fact and fiction, and how I can get readers excited about characters and stories where learning and science -- instead of conflict -- solves problems.

Jon, people might know you from the "Leo Geo" books, and in one book the character travels through the layers of the Earth and I'm sure you had to do research to get a lot of those details right. Talk a little about what was different with this book?

Chad: "Leo Geo" is more of a shopping list of geology terms, while "Volcanoes" arms the reader with analytical tools to understand volcanoes' many characteristics using just a few key concepts.

In "Leo Geo," I had the character present a wide myriad of geology facts. I had more to work with; Leo went through all the Earth's layers. With "Volcanoes," the information is more specific. At first, I worried that I was going to have to focus on complicated, in-depth terms and concepts about volcanoes if I wanted to have any chance of filling a whole 128-page book.

What I realized, though, was that as I started writing and thinking about the basic facts about volcanoes, my own knowledge was too compartmentalized. I had learned (and I suspect other learn the same) to look at/identify volcanoes as you would Pokemon. "Oh, look, there's a composite volcano! Oh, and over there, that's a shield volcano!" This treats different volcanoes like separate types of phenomenons. In reality, though, it's more like a continuum. Volcanoes can exhibit traits of one, but look like another. A volcano can start as a shield volcano, but turn, over time, into a composite volcano.

I know that's a long answer, but that's the difference between "Leo Geo" and "Volcanoes"; I want to give readers analytical tools to understand volcanoes, and not just a shopping list of volcano facts. What is the cause of the aforementioned volcanic continuum? It actually has to do with what magma is in a volcano! What determines that? Over the course of the book, I introduce facts about volcanoes, starting from where they are formed and work my way out, making sure to reinforce, several times, the idea of a continuum.

Maris, as an educator at the New England Aquarium in Boston, you're coming at this as a very knowledgeable non-scientist who has to explain a lot of difficult concepts. What was different for you making the book as opposed to guiding field trip through the aquarium?

Wicks: I actually left my education job at the Aquarium a few months ago; it became too difficult to balance both teaching and comics! So my role as an educator has certainly evolved and transitioned into my comics.

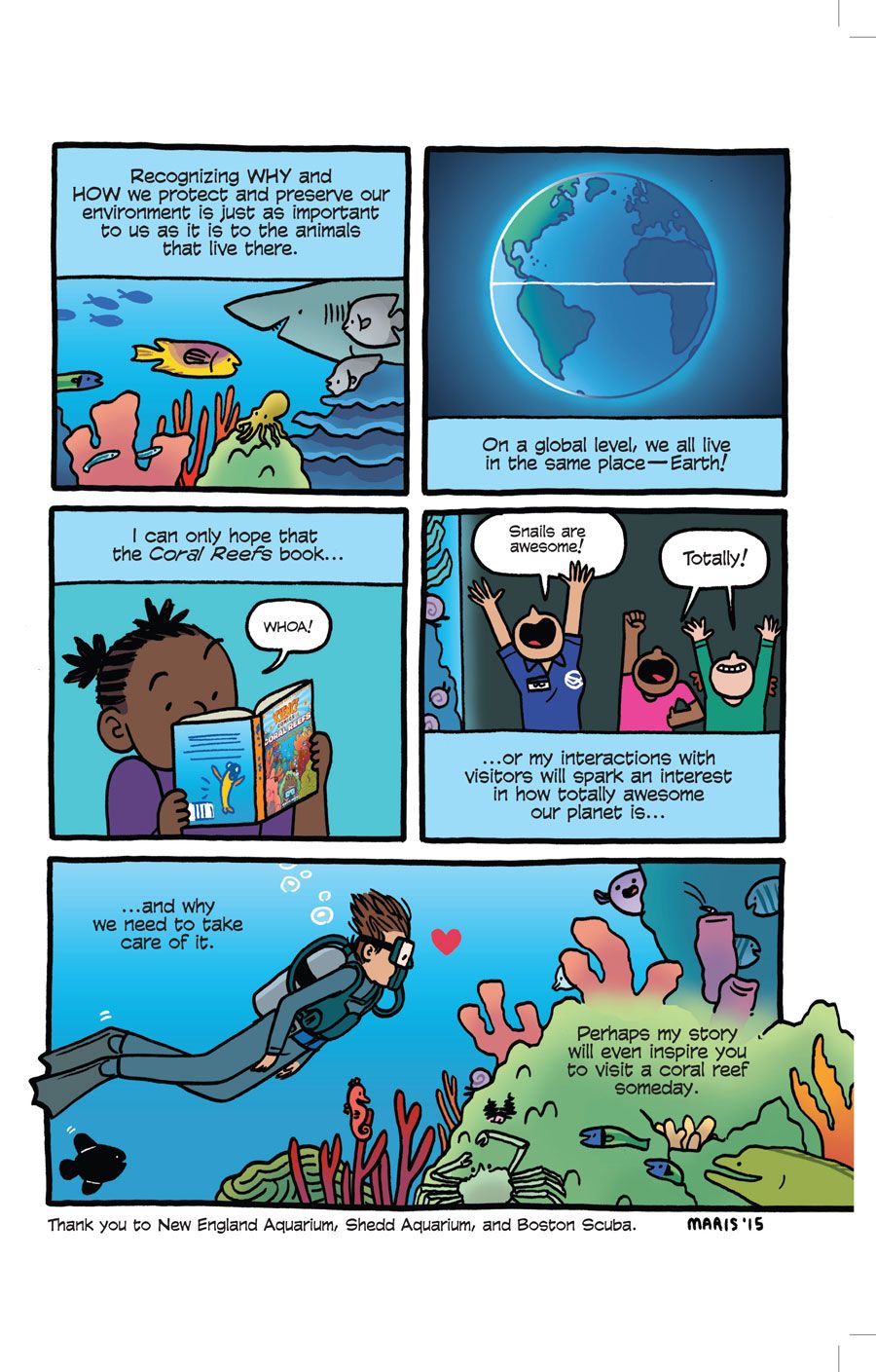

I think the hardest part of making comics about science topics that I am passionate about is, I'm not physically there, talking to you. So much of my role as an educator involved one-on-one conversations, where I could describe elaborate relationships in the ocean using ridiculous faces, broad hand gestures and even interpretative dance. Ask me about my jellyfish impersonation sometime! In comics, I have to translate my educator persona into words and pictures. I can only hope that a fraction of my in-person enthusiasm got bottled up in these comics.

What do comics provide you to help in terms of teaching science, and what was a big challenge to convey?

Wicks: Images -- whether they're graphs, diagrams, or reference illustrations/photographs -- are already heavily present in science and science education. It just seems natural (to me) to use comics to stitch this imagery together with a narrative. All too often, subjects in school are broken down and separated from each other. This is sometimes necessary, but it also can prevent us from seeing connections. Everything that we have done or observed as a species is connected through history. Advances in science are often accompanied by breakthroughs in literature, art, music, mathematics, philosophy, etc. To be able to see these connections helps us to be better creative and critical thinkers, and, as a result, better problem solvers.

Chad: First, comics are wonderful for showing the passage of time in a concise, understandable way. The Earth's crust moves at a rate of about 4 cm a year. Pretty slow! With comics, I can speed up natural processes that take eons.

Also, I can use visual comparisons. For example, I've drawn a spread where I talk about the viscosity, or thickness, of magma. It can be hard for young readers to understand the idea of "thick" liquid, let alone thick, melted rock, but if I put images of magma next to, say, peanut butter or honey, they'll get the idea.

What was your favorite thing about researching your books?

Chad: I think my favorite thing that I did was watching the videos of volcanic eruptions made by Katia and Maurice Krafft. Those two were really on the forefront of volcanic observation, and their videos are truly breathtaking. I haven't been fortunate enough to visit an active volcano, and while I've seen many a science specials on PBS or National Geographic about volcanoes, the Krafft videos are, bar none, the most spectacular.

Wicks: I got scuba certified! Then, I went to the Bahamas to live on a boat for 10 days, where I dove on coral reefs and helped to collect fish for the New England Aquarium! It was awesome!