Welcome to the CBR SUNDAY CONVERSATION, a weekly feature where we speak in-depth -- and at-length -- with some of the most interesting members of the comic book community. These discussions run the gamut in terms of topics, from current projects to classic stories, talking trends, tastes and wherever else the conversations lead.

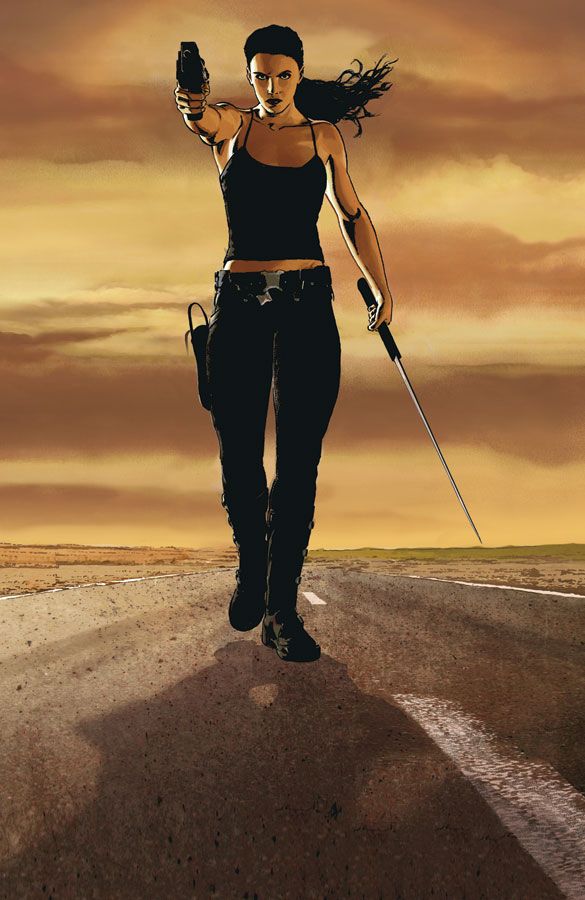

Whatever news of science's triumphs and pitfalls writer Greg Rucka doesn't filter into his fiction, he shares with readers through his letter columns and Tumblr blog, Front Toward Enemy. Not only is "Lazarus" -- his ongoing Image Comics series with artist Michael Lark -- a product of his research into transhumanism and economics, it also provides a venue for the writer to develop his own opinion on the ethical questions involved. "Lazarus" is as much the journey of the nigh-invulnerable Forever Carlyle and her dystopian world as it is the working laboratory of a writer deeply concerned about his own world and where it's headed.

CBR News spoke to Rucka about the science that drives his speculative fiction, his own curiosity and the fears and wonders it inspires in his work and waking life.

CBR News: Anyone who stays past the credits and delves into the back-matter of those "Lazarus" issues can see, pretty clearly, that you have a deep curiosity. It's not just research or fact-checking homework. It drives your fiction. Do you think writing speculative fiction like this is a kind of research in itself?

Greg Rucka: As a whole, I think a lot of us writers use our writing to try and determine what we feel about some things, as well as to express or exorcise those things that are bothering us. The older one gets, the more one realizes that very few things are entirely bad or entirely good, though there are some. I've just turned 44. The rage of the young man has been replaced by the burning anger of the old man. That anger turns out to be more directed, I think.

Greg Rucka Talks Loyalty, Lies & Love in Second "Lazarus" Arc

Would you go in for any of these procedures alluded to in "Lazarus?" Is there a line for you in terms of what you'd be willing to do cheat death?

When science is growing brains in vats, there is good and bad. There are, as always, ethical issues to be addressed. At the same time there are people out there watching loved ones suffer from Alzheimer's or other forms of dementia. If you had a way, medically, to maintain that tissue or that organ in a healthy fashion, that could legitimately not alter the person, wouldn't you take it? If you could grow a new set of lungs to save someone dying of lung cancer? It's very difficult for me to look at a lot of the medical stuff and say it's intrinsically wrong. But there are questions we have to ask about it. Sports science is doing it already. We have blood-spinning, all sorts of manipulation of athletes. At the same time, we're screaming about steroids in baseball. At what point is it legal? At what point is it ethical?

Do you think that's a question of morality or of a level playing field?

I think the two can't be divorced.

In all this reading, have you ever come across something that's genuinely scared you?

There are things I've read that I don't put into my writing and I don't share in the letter columns.

I do worry as a parent what the world's going to look like in ten years, when my son is 23 and my daughter is 20. I do worry. What are we leaving them? Are we leaving them anything? The environment is in a horrible situation and getting worse. I have some faith in humanity's ability to solve a problem when we have to. We did reach the moon. I worry that the moment when we had to had already passed us by. I really do worry that.

Do you think you're writing down your nightmares so you don't have to experience them in your sleep, when you're more vulnerable?

I don't sleep well. [Laughs]

Really? I'm sorry to hear that.

Yeah, I really don't, for any number of reasons. I've actually been trying to track my sleep for the past couple months and I don't sleep very well at all.

Do you think writing about a dystopia and researching all this is in any way therapeutic, or does it just exacerbate the problem?

The problem with learning stuff -- and this is the thing -- there's so much information coming in, much of it unpleasant. There's the temptation to bury your head in the sand and debate whether the PS4 or Xbox One is the better console.

Hey, that could well be my topic next week, so you calm down, sir.

[Laughs] But you know what I mean.

I do.

And there's a reason we do because you can't look at deforestation statistics all the time. But sometimes the best I can do is climb up on my tiny soapbox and scream at the top of my lungs. And if two people write letters, added to my one, that's three letters that go to the senator's desk. Which is better than none. When it comes down to it, we are going to have to save ourselves, and to do that we have to acknowledge that we can. And one of the things that has happened is that we've been led to believe that we can't, that it's too difficult and too complicated. Of course, that way death lies.

Greg Rucka on Collaboration, "Lazarus" Origins & Warren Ellis

If you were to drop everything and start over as a scientist, what branch of--

I'd be a physicist.

That's a lot of math. I was under the impression you didn't play well with math.

Yeah. There's a piece of me that wishes that I had fallen in love with the numbers enough to understand what they were trying to say and stuck it out long enough that I could speak it. I find theoretical physics fascinating. I find the potential there daunting and beautiful. What little I understand constantly leaves me with a sense of wonder that I think is miraculous. The idea that my moving this pen on my desk from the right side to the left side -- that act alone -- is impacting the universe in such a way that we'll never see it. I just impacted the orbit of Jupiter. I impacted the orbit of Jupiter! It's going to be 100 million years before it matters, but I did it. That's amazing. You and I are sharing instantaneous conversation, but we're not. We're each in slightly different pockets of time.

I think it's interesting that you chose something that's arguably so abstract. It's right there in the name. People might choose something with more easily defined practical applications, more immediate results.

Well, but the argument there is that so many of these discoveries in that work has never had a literal practical application, yet we got an atomic bomb out of it.

Fair. That's a pretty big whoop, if we're being honest.

The big thought leads to the literal advance. It's got to start somewhere.

It still sounds a bit like delayed or even deferred gratification though, doesn't it? It's noble, don't get me wrong.

Well, yes. [Laughs] I don't think there's anything wrong with that. We live in a world where people expect it NOW! I'm not sure I ever would have made it. I don't know that I'd ever have contributed anything, but I think I could have been very happy having a love affair with physics.

Is there anything that comes close to that sense of awe in writing?

Sometimes I'm fortunate enough to read work by others that I look at and I go, "I could never in a million years write that. How did they do that? How did they make that thing?" It happens far more often than it doesn't, honestly. There are a lot of writers out there who do work I think is sublime.

Rucka Talks Thematics of "Veil," Los Angeles & Staying Creator-Owned

To someone who's not a writer, that probably sounds awful.

Really?

I think I get what you're talking about. But let's look at that objectively. To say, "I could never do that no matter how long or hard I try," and to continue writing in spite of that, sounds almost despairing.

But the problem with that is to imply that all writing is the same, and it isn't. One of the reasons everybody says they want to write and so few do comes out of that misconception. I don't stay up nights going, "Wow, I don't write like Fraction. I don't write like Jeff Lemire. I don't write like Scott Snyder or like Brian Bendis." I don't go like that and wish I did. "Oh my god, I wish I wrote like Jason Aaron." I love Jason Aaron's writing. I mean I love it. I could eat it with a spoon. But that's writing like only he can do, which makes it all the more wonderful. I know my own writing and what I can do. Sometimes I hit my numbers really well and I do it well. One of the joys of writing is that it isn't a static profession. The desire to make the thing you write tomorrow better than the thing you wrote today is a driving force. It is a process of self improvement. I don't believe in competitive writing. We're not all in the starting blocks. I'm competing with myself because it's the only person I can compete with.

What is your favorite part about being human?

[Laughs] You have a list of these.

I may have some things written down. I think it's worth asking since "Lazarus" pushes the definition.

My favorite part of being human? I know what a lot of people would say, but I'm not gonna say that. Being able to know I am. Higher thought. I like that we can look up at the stars and understand that we're made of the same material. I don't think dogs can do that. And I think dolphins can't.

Why do you suppose that's important?

I don't know that it is. It's just what I love. I love that we have the ability to ask about ourselves. That way we have a future. This is a very deep conversation. How did this happen?

We can reel it in a little. We know you read a lot of scientific news, but how about some of those works of fiction that inspire that same awe? What are you reading these days?

I've got to tell you, one of my favorite sci-fi books is Joe Haldeman's "The Forever War."

Yes!

I loved that book to death. We could spend hours just on that. I loved Dan Simmons' "Phases of Gravity." I like a lot of his stuff, but I really loved that one. It isn't really sci-fi, but a wonderful novel nonetheless. I cut my sci-fi teeth kind of late, coming to it by way of William Gibson's "Neuromancer." That book had a profound effect on me and I believe you'll see a reference to it in the letter column for "Lazarus" #5. I was asked why we leave so much in the back-matter that doesn't make it to the story itself. I understand that frustration, but "Neuromancer" is sort of my bible for this. Gibson doesn't explain squat!

With that book in particular he really does throw you right in there, no hand-holding.

You work it out by context.

He's like the Mamet of science fiction. There's nobody saying, "As you know, we're brothers-in-law."

Exactly.

Let's end on a difficult question. We talked earlier about the willingness to use fringe science to cure disease or replace existing tissue, but how far would you really be willing to go? Would you agree to wings or robot legs? A wheel?

I lose my legs. They ask me if I want these more traditional robot legs or wheels. I'm probably going to go for the legs. They pitch me the wings, I'm going to ask whether it's an aesthetic choice or what.

It's an elective thing, more cosmetic than anything else, in all honesty.

Yeah, and see for me, no. Now, how would I feel about somebody else doing that? That's kind of like asking me how I feel about some guy who's got a full-face Maori tattoo out in Topeka. That's his choice.

For more on Greg Rucka follow him on twitter @ruckawriter and tumblr at http://ruckawriter.tumblr.com