Marvel's "Captain America: Civil War" was released on Friday in the United State and debuted to $181 million in its first weekend at the box office. Mother's Day happened in the same weekend, and it speaks to a core theme which threatens to shift the numbers between the #TeamCap community and the #TeamIronMan community.

Loss.

The film was loosely based on Marvel Comics' "Civil War," the event series published from 2006-2007, in which a fight between superhumans on American soil leads to the destruction of a small town, and a lot of casualties. The U.S. Government passes The Superhuman Registration Act, requiring all superheroes to work as officers of the government. Those who don't register are considered criminals, hunted down, captured and imprisoned in a high-tech Guantanamo Bay detention camp-like installation.

Spider-Man, Black Panther and 9 Other Things We Love About "Captain America: Civil War"

In the film, the global devastation and loss of life due to various Avengers battles leads over 100 nations around the world to establish The Sokovia Accords, based on the devastated nation of Sokovia in "Avengers: Age of Ultron" film. The Accords set the guidelines for the regulation of, and military control over, superheroes.

At the core of this grand drama is a mother, a Black mother played by actress Alfre Woodard, whose son died in Sokovia while providing humanitarian services for the nation's residents. Woodard's character confronts Tony Stark, AKA Iron Man, after an MIT presentation in which he offers grants for every student in attendance to design and determine the future with their imaginations and perseverance.

Stark's presentation uses virtual reality tech to show the last time he saw his parents, in 1991, before they were killed in a car crash. The last time Stark saw his stern, proud, self-righteous father, and his loving, sympathetic mother.

The confluence of a son's loss of his parents with a mother's loss of her son, the painful reenactment and the confrontation a few minutes later, served to rattle Tony Stark to his core, to propel him to support The Sokovia Accords in order to keep The Avengers intact by keeping them under the supervision of the Military Industrial Complex.

But there was another layer at this commonality of loss. The point of unity between a White man of wealth and social stature, and a Black woman, implied to have considerably less means. This was a brilliant and timely move on the part of Marvel Studios, to cast a Black woman as the mother of a killed male child.

While only for a few minutes, her time on screen served as a cultural reflection of the aftermath of Black male death and murder in America. Future lives and accomplishments cut short, reduced to statistic and afterthought. When the mother reached for an unknown object which Stark expected to be a gun, it turned out to be a picture of her child.

The gravitas of this scene, played to full effect by Woodard and Downey, Jr., implied a multilayered guilt for Stark; of power, of class, and maybe of race intermingled with class.

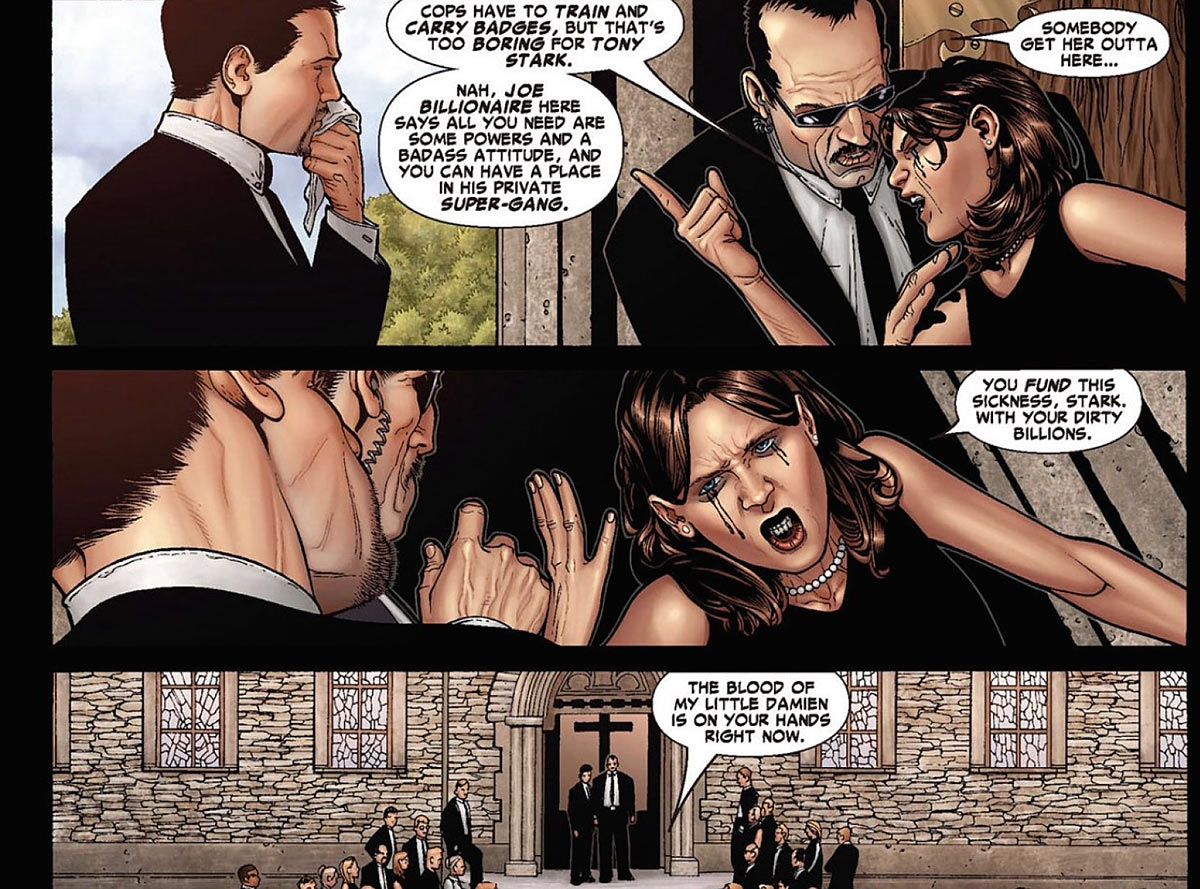

In the "Civil War" comic book, a similar scene was shown, but the mother was White. That comic book was published before the murders of young Black men became a re-galvanized subject in the national consciousness. The scene rested on racial issues, and transcended them at the same time, when the secret of how Stark's parents died is revealed in the film's third act.

Stark, as Iron Man, sees video evidence that his parents were killed by the Winter Soldier, a formerly-programmed American soldier turned assassin for the Russian government. Bucky Barnes, Captain America's best friend. The friend he defends and protects with his life; defends and protects to the point where he knew his friend killed Stark's parents and kept it a secret from him.

The video footage showed Winter Soldier punch Stark's father to death, and choke the life out of his mother. A slower, more intimate murder, for the parent Stark still felt love from, the one in whose physical and psychological womb Stark found humanity and solace.

In that moment, Stark and Woodard's character were bound by chains greater than points of view, financial status and the social programming of prejudices built on a legacy of plunder, violation and greed. When Stark as Iron Man fought Captain America so he could get to the Winter Solider, he said, "He killed my mom."

Not "Mother." "Mom."

This was a man speaking with a boy's sense of heartfelt injustice, and a feeling of righteousness above all. If I was #TeamCap before that revelation, I certainly could not be afterward. Stark had his mother taken from him. A mother had her son taken from her. The irony of this theme, presented on the same weekend as Mother's Day, is an eerie reminder of the thematic loss that made classic Marvel comic book stories work so well.

I don't know about you, but after the film was over, I was neither #TeamCap nor #TeamIronMan. I was #TeamMom.

But I understand where Iron Man was coming from.

Joseph Phillip Illidge is a public speaker on the subjects of race, comics and the corporate politics of diversity. In addition to his coverage by The New York Times, CNN Money, the BBC and Publishers Weekly, Joseph has been a speaker at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, Digital Book World's forum, Digitize Your Career: Marketing and Editing 2.0, Skidmore College, The School of Visual Arts, Purdue University, on the panel "Diversity in Comics: Race, Ethnicity, Gender and Sexual Orientation in American Comic Books" and at the Soho Gallery for Digital Art in New York City.

Joseph is the Head Writer for Verge Entertainment. Verge has developed an extensive library of intellectual properties for live-action and animated television and film, video games, graphic novels and web-based entertainment.

His graphic novel project, "The Ren," about the romance between a young musician from the South and a Harlem-born dancer in 1925, set against the backdrop of a crime war, will be published by First Second Books, a division of Macmillan.

Joseph's newest comic book project is the upcoming Scout Comics miniseries "Solarman," a revamp of a teenage superhero originally written by Stan Lee.