Back in 2008, Brad Guigar, Scott Kurtz, Dave Kellett and Kris Straub co-authored How to Make Webcomics. There weren't too many other books on the topic then (and it looks from Amazon like there haven't been many since), and with the backing of some of the biggest names in webcomics, How to Make Webcomics became the standard reference.

The world moves quickly, though, and the past five years have brought us the iPad, comics on tablets in general, social media, same-day releases for almost all major comics, Kickstarte, and the demise of DC's Zuda and of Joey Manley's Webcomics Nation group of webcomics sites. It's a different world, and it's time for a different book.

Now Guigar, flying solo, is producing that book, and he's doing it via Kickstarter. The Webcomics Handbook is a sequel to How to Make Webcomics, and it's based in part on Guigar's subscription-only website Webcomics.com. I asked Guigar to explain what he is doing with this book, why he is doing it on Kickstarter, and how the webcomics scene has changed from his insider point of view.

Robot 6: Is this a sequel or an expanded edition, and will this book include some of the information in the first book?

Brad Guigar: This is a sequel to the original, but it does include some of the content from the first book — updated. I wrote three chapters of the original How to Make Webcomics book and several sidebars in the other chapters. Some of that information is still solid, some of it needs to be updated, and some of it needs to be re-addressed.

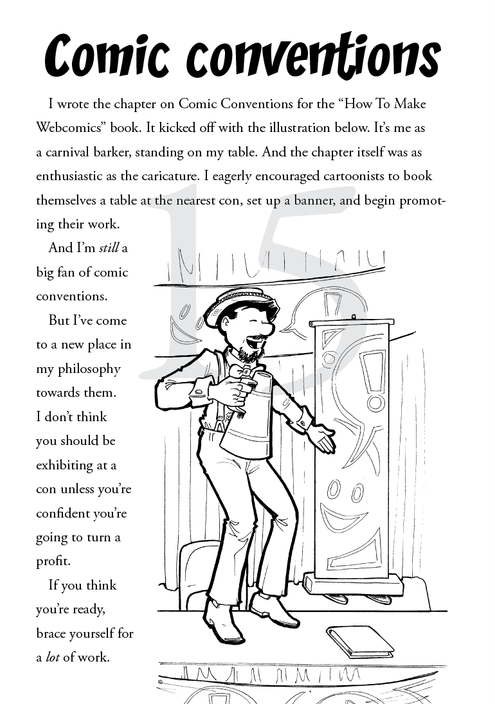

Here's a great example: When I wrote the chapter on comic conventions, the opening page had a self-caricature of me, standing on top of a convention table, dressed like a carnival barker. The chapter on the same subject in the new book reprints that illustration, and I write how I think I over-amped on the importance of comic conventions, and how my personal philosophy has matured on the subject. I have a whole new criteria when deciding whether to do comic conventions and I share the thinking behind that in the book.

What areas are you adding or emphasizing more strongly compared to the first book?

Two chapters have been included that weren't even topics in the first book — social media and digital downloads. But the chapters on business, advertising and marketing each get several pages of extra information over the other chapters. I also have a chapter on writing, like the original book, but I've included a chapter on the general topic of creativity that I think has some very strong material.

Conversely, what seems less important?

Honestly? Comic conventions are a little less important than they were in the first book.

How did the book and the website influence one another?

Webcomics.com was a big part of my writing that book. For starters, I have a goal of trying to update that site every day with something meaningful and significant. I started in 2009. That's a lot of time to cover a lot of topics. So I had some good raw material to work from. Secondly, I could gauge interest in different topics by the reaction of my members. If something caught fire in the comments, I knew it would be important to drill deeper on that subject.

Looking at the Kickstarter, I see you are offering digital copies of the book as premiums. Will it be available on other digital platforms after the Kickstarter is over?

Yes, but I'm not able to share any details at this point.

Is the first book available digitally?

I'm afraid not.

The webcomics scene now is very different from the way it was in 2008. What do you see as the important changes?

The biggest change is that we're not mavericks in a wild frontier anymore. At one point, we web cartoonists could do almost anything and get a huge push out of the sheer novelty of what we were doing. Now that we're sharing space with Batman and Spider-Man, we've got to bring our A-game to get noticed.

Is it still possible to make a living from webcomics?

It always amazes me that that's even a question — but not for the reason you might suspect. (And I write about this in the book, as well.)

First off, of course it's possible to make a living in webcomics. What amazes me is that people seem to think that it should be somehow easier to make a living in webcomics than it is to make a living, say, as a comic artist for Marvel ... or any other creative profession (professional actor, musician, etc.).

And here's why: Although "webcomics" has removed a lot of the traditional gatekeepers that were in place under traditional publishing structures, there's one, stubborn fact that will always remain: Doing this — and doing this so well that people will pay you to do it — is a difficult task.

Anybody can do a funny cartoon once. Everyone has probably told a story in an interesting way at least once in their lives. No problem. But to create something on a regular basis that's consistently high-quality work? For a month? For a year? For several years?! Herculean.

THAT'S why there aren't more people making a living in webcomics. It's also why there aren't more people making a living as actors in movies ... or as professional musicians. 'Cause this is hard. The ability to self-publish on the Web (and in print ... and, now on tablets) will get you in the door. But the rest is up to you.

How has the model changed?

The model has not changed — not the basics of it. But there's a tremendous increase in the variables that you have to apply to that model.

What do you think about having your own site vs. being part of a collective vs. putting your comic on a group site such as Keenspot?

Running my own business was crucial for me. I don't think I could have gotten to the point where I felt comfortable leaving my day job otherwise. Is it better than a collective? For me it has been. I know other people who feel being part of a collective works well for them. If it works, it works.

How have the iPad, iPhone and Android devices changed the webcomics scene?

The tablet market is a huge part of webcomics. There's a tremendous amount of potential there for cartoonists. And we're really just beginning to see the full extent of the effect it's going to have on what we do.

In part, its effect has been to push the pendulum away from independent comics and back towards a traditional model of publishers and distributors. ComiXology, Apple, Amazon ... these companies are filling some very familiar roles in comics. I'm not saying that this is necessarily bad, but it is a shift in webcomics business that we have to be familiar with.

Do you regard digital-first comics on those platforms as webcomics?

Yes and no. Yes, they're webcomics. They're comics delivered through the Internet. Done.

But I'm a geezer. I've been doing this every day since February 2000. This has been a big part of my life. And, for me, "webcomics" will always convey a sense of independent comics. Folks like Scott Kurtz and Dave Kellett and Kris Straub — my co-authors on the first book. For me, they're what webcomics are all about. Follow their careers — they each exemplify the very best of what we all hoped for in the late '90s. Same goes for Mike Krahulik and Jerry Holkins and Kate Beaton and David Malki and Ryan North and Erika Moen and a whole metric ton of other brilliant people who I'm going to hate myself in the morning for not listing. It's not about the mechanical method used to deliver comics. It's way more important to me than that.

What do you see as the biggest challenge that any aspiring webcomics creator faces today?

Doing it again tomorrow.

And what advice would you give that person?

The words that I want on my tombstone: "It's impossible to get worse at something you do every day."