Comics fandom is a place of diversity. Among the fans -- both men and women -- there is no sameness: we are thin, tall, fat, short, flat chested, athletic, curvy, skinny and proud, all gathering to freak out about our art of choice. But does that art truly reflect the real world? Do we see ourselves represented fairly in the pages of our favorite books, or does it seem that a single idea of "attractiveness" tends to dominate the page? Does the comics world echo too many of the same tired and rigid expectations that have been accepted as the norm for far too long?

It sometimes feels that way.

However, there are creators unafraid to do things differently -- writers and artists committed to delivering work representing people of all shapes, sizes and colors. CBR News spoke with three such creators from the vast pool of comic book talent -- "Drumhellar" artist Riley Rossmo, Eisner-winning illustrator Hope Larson and "Rat Queens" writer Kurtis J. Wiebe -- in a special roundtable discussion to explore the reasons behind a lack of diverse body image in comics, the responsibility of editors and publishers to allow creative freedom and how they think readers have the power to change the industry.

CBR News: What are your impressions on the current state of diversity, especially around body image, in comics? Do you see changes in the industry?

Kurtis J. Wiebe: The truth is, I don't feel like there's been a lot of change when it comes to the mainstream stuff. We get a lot of the standard stuff we've seen all along as far as body type goes. Especially when it comes to female characters, it's the same thing we've always seen. There hasn't been a lot of exploration into characters in superhero role that have normal features, or features you'd see in a person everyday, and I don't feel like there's a lot of experimentation. If creators were to go that route, there would be people who could identify more with those characters. I just think it would be interesting if there were a bit more experimentation, you know? Especially if we're talking Marvel and DC. Like, let's see what the fan reaction would be! We're already seeing with a lot of the female led stories with "She-Hulk" coming out, and there's a huge demand for female-driven stories, where a few years ago that wouldn't have gone over as well. Maybe we should just keep trying new things and see what happens.

Hope Larson: I can't speak for superhero books because I don't read anything like that. Most of what I read are indie YA comics that are published by book publishers and Manga. I can't say that there's a whole lot of body diversity going on in any of those that I've seen. I'm struggling to come up with any examples of lead characters that are actually fat, or overweight or however you want to put it, in books I've read recently. In YA stuff, at least stuff that's domestic, authors make an effort to draw normal/average body types but they're still on the thin side of average typically.

Riley Rossmo: I think that there is some progress, but I don't think its big steps. For midrange publishers, like Oni, there's Ross Campbell's "Wet Moon" that has some great body diversity. That's my go-to thing as there's a wide variety of representation. "Love and Rockets" has some diversity, and I think they're an exception because they have an age range that more mainstream stuff doesn't necessarily have in it's depiction of women. But there's still a lot missing. It's most apparent to me, especially when you look in mainstream superhero books, when you look at the age range and morphology for different body types. If you look at how the men are represented, there's a huge range -- super skinny, obese, young, old. But with women, especially in mainstream books, its either Aunt May or Mary Jane. There's no middle ground.

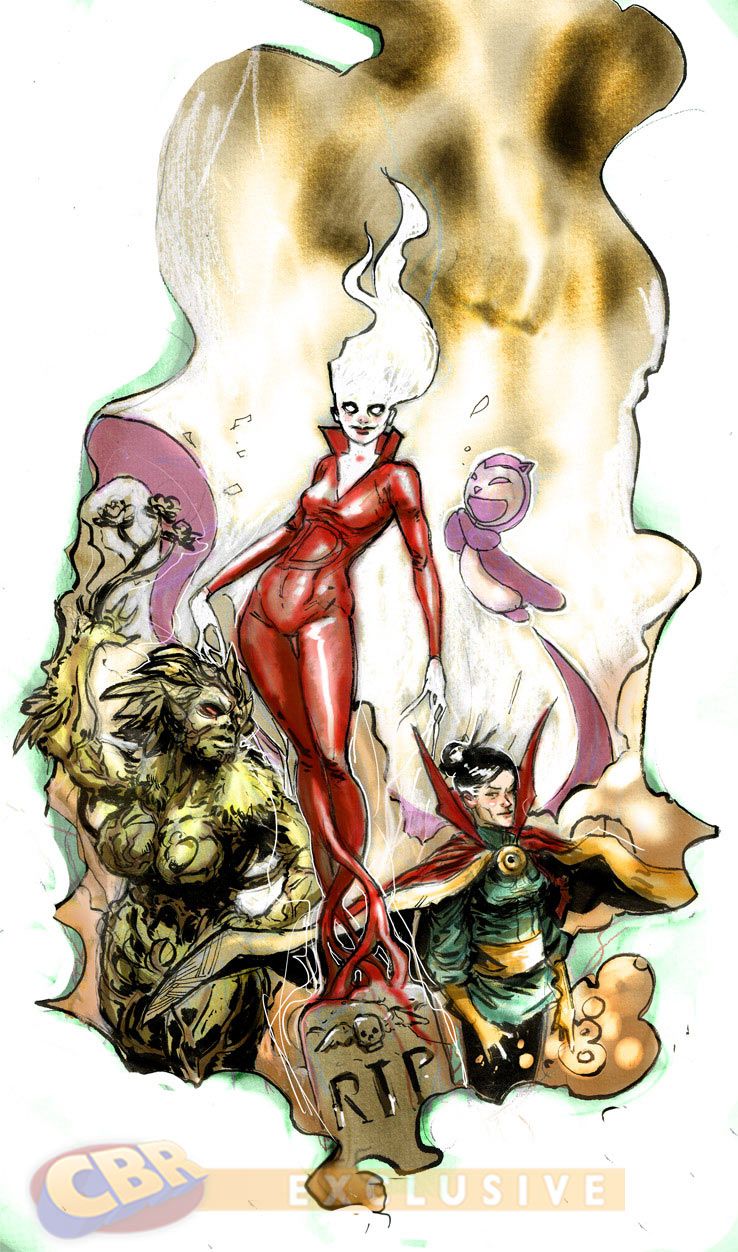

With male characters, you get ones like Wolverine, who's short and hairy, and if there were a female character like that, it wouldn't fly. Superhero comics represent a lot of industry sales and they aren't necessarily representative of the readership.

What do you think the message of the sameness in depictions sends? How does this influence fandom? Do you think anyone that's a lifelong comics reader has their perceptions influenced?

Larson: I think any time you're fed any kind of image, that gets to be normal for you, especially when you see it over and over. It gets to be normal, whatever that image may be.

Wiebe: It's weird that there's a difference in the levels of diversity we see between Marvel/DC and the smaller publishers. I notice that there seems to be more diversity where there is less editorial control. I think it's interesting, and I think it means that people don't want a standard where everyone looks the same.

It does affect the readership. As a male reader, pretty much every character I read is usually a tough, muscular guy. It ties into the general perception of what men are, and what we're told to be through film and advertising. And Casey, this is something we've talked about before, but you don't hear it mentioned that often -- when it comes to body image, the male side of things isn't talked about much and I think this is a good opportunity to do it.

Riley, part of why I wanted to have you be a part of this conversation is because of how you depict the lead character of your series, "Drumhellar." He's not some muscular tough guy, but a very average, maybe even nondescript, lead character. Tell me about his character design.

Rossmo: When I was designing Drum, I borrowed a lot from character designs where I felt like it was easy for the readers to inject themselves into the character. I'd been reading a lot of "Tintin" stuff, and why Tintin is interesting and relatable to me is that he doesn't even have features. He's more like an icon. It's easy to project yourself into that. On top of that, he's kind of handsome, but his head is a sphere. So you're reading that into his character -- like, I don't know why I think Tintin is handsome, but I do. So in creating Drum, I wanted to borrow that. He's just a guy. And Tintin's not hypertrophic, he doesn't blow things up, sometimes he shoots stuff but he doesn't seem to kill people. He just shoots in the direction of bad guys. I think that makes a more accessible character.

What do you think the risks are by not showing diversity in body type?

Larson: I always try to have a little range in the books I draw. I think it's more welcoming to readers to see someone who looks a little like them. Even though I have a limited amount of characters and can't have the full range of body types represented each time, I like to at least hint in one direction or the other so it feels more like the real world.

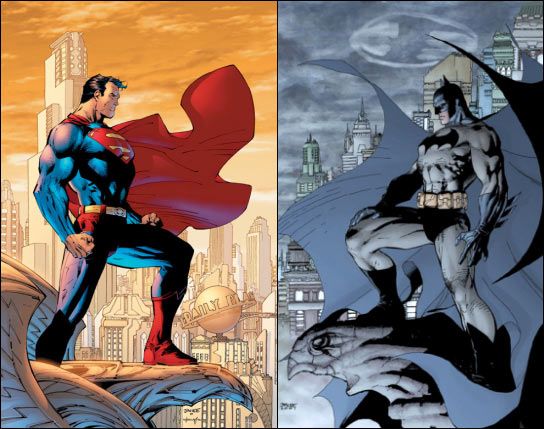

Rossmo: By having different body types, it makes it easier to tell your story. I was reading a book recently that had both Superman and Batman both out of costume and they are the same guy. I like to try and include even something small, like a bulbous nose. If you look back at superhero comics for the past 15-20 years, you wouldn't find that many characters with round noses, right? And it helps me because I don't have to draw as well! I'm just like, "Oh, there's the round nose guy. Or the hairy guy. Or the girl with freckles."

Larson: Since I write for teens, I always try to make sure that I have characters with features, like big boobs, but done in a way where they aren't sexualized. I know that can be a thing when you're an adolescent. It's so complicated, and I just want to be welcoming to my readers.

Wiebe: I don't read a lot of superhero comics either, but there are definitely ones that come to mind when you bring up the subject of anatomy, like Power Girl. I don't know anything about that character at all except the fact that she has a rack. And that's a bad thing! There should be more than that.

With "Rat Queens," a very important part of the process in defining the appearance of the characters was deciding how they looked related to who they are. How would their appearance make them feel about themselves? How would it make them feel about the world? It's not about just making them look good or have a certain figure, but it was about informing who these characters are. I think that's important. When I sit down to write Betty, for example, I mean, she's tiny. And she's very skinny. How would that change her worldview compared to Dee, who is curvy woman of color? It brings a lot more depth to characters when you take this stance, incorporating their physique into their personalities in a way that makes sense, versus something like Power Girl who is predominantly known for her body instead of who she is.

When you're writing a book and not doing the art, how do you communicate the appearance of the characters to your artist? Are you making intentional choices or do you let them decide?

Wiebe: I'm lucky because when Roc draws people, there's never the question of whether or not he's going to make them look realistic. He just has this ability to draw women and men very naturally. When we sat down to talk about "Rat Queens," there was maybe one line of physical description for each character, but it was truly focused on their personalities. There were some things about fashion, since we're adding a lot of modern tropes into the series, but it was always directly tied to their personalities, and how they looked the way they did and wore the things they do because of who they are.

Larson: I don't think that I ever specify body type at all when I'm writing for other artists. I give them age, some character description of what they're like and what they do, but not really a lot beyond that. And now I'm thinking that I should probably be more specific about body type because an artist might not consider injecting a range of physical types into the story.

Rossmo: I don't know if I think about it usually, either. I can't remember the last time I worked on something where there was specific direction. I just draw the people how I draw them, and like I said earlier; it's just easier for me if they're shaped differently from one another. From a character design perspective, it makes a lot of sense to me to add different body shapes for men and women, like a super short guy or something. It works to differentiate them. What do you guys think about the characters in superhero comics? Like, how they're supposed to be these ideals? It makes it -- weird, I think. We were talking about superhero books and I was thinking about Cliff Chiang's "Wonder Woman" and how she's a little different.

Larson: She's a bit more ripped, right?

Rossmo: Yeah, she looks like she works out. She's got big muscles.

Larson: Yeah, I've seen pictures of her. She looks like she actually lifts. I have such an appreciation for really built women, and I wish that was represented more. That would make me actually want to read superhero comics -- if there were really strong looking women as opposed to these ones with really dinky, superficial looking muscles. The powerlifting thing is so prevalent right now, and we all know what female athletes look like. We know what bodybuilders look like. I don't think there's much excuse for not having more range for realistic looking superheroes.

Rossmo: I thought it was cool that the editorial team didn't crush it. All of the previous designs I think of for Wonder Woman show her being more willowy with big boobs, so seeing Chiang's version definitely shows some progress.

Wiebe: I've been doing research for a new project I'm working on about a Thai female kick-boxer. They are all so built and so cut from their training that it's sometimes difficult to distinguish if they're male of female. I got the sketches back from the artist on this project and a lot of people who've looked at them said they couldn't tell if it's a guy or a girl -- and I think that's interesting. That's something I'd like to play with. It's another thing you don't often see in mainstream comics -- transgendered characters. It's something that's not really talked about, which could be interesting to do.

You see it out there a bit, like in "Saga." That book has tons of variations on characters. There are different shapes and sizes of men and women, homosexuality, some characters are almost transgendered -- and yes, it's a great book overall, but I think there's more to the success of it. It's hitting these subjects and showing this range that other books are failing to do.

What about times where diversity is just for the sake of diversity, and not at all an authentic part of who the characters are?

Rossmo: It becomes weird when you can see a series making these choices about diversity just because. Where you can tell it's like a checklist, just to artificially create something where the attributes become the character, versus the character embodying these things. I feel like you can really tell when it's genuine and when it's not.

Larson: It's hard. As a writer, I try to always think about this stuff, and it doesn't always work. I feel like every time I do a book, I think I could've done a better job representing diversity in a bunch of different ways. You can't check every box every time, all you can do is be aware of the issues and try to tell the best, most progressive story you can -- that, first and foremost, is a good story.

Let's talk about the point of view of editors and publishers -- do you think they view it as a risk to show different things, like transgendered characters or body diversity?

Wiebe: Oh yeah. Definitely, if we're talking about more mainstream ones. When those characters do come out, the ones that are different, it's because people were basically screaming their heads off about wanting to see it. It almost feels like it has to be proven that there's an audience for it before they'll take a risk on something.

Larson: I've never had any issues, but I'm working in such a different world.

Rossmo: Same for me, I've drawn one "Superman" comic and no one ever said anything to me about what I did. But one time I remember getting called out was when we were doing "Green Wake," Kurtis -- although that was more about violence. It was more of an issue than even the nudity.

Weibe: I think it pertains to part of this discussion -- showing sexuality in comics-- because we got edited on one of the two sex scenes we had in "Green Wake." The last page was a guy going down on a girl, and that got cut. We had to make the change. It's weird, because the rest of the scene was fine, but that was too much?

Rossmo: You were squeamish about the innards. You were like, "I don't really feel comfortable with some of the gross stuff."

Wiebe: That was because you showed two guys pulling out a guy's intestines and eating them in bed! It was weird!

Larson: I've gotten called out on sex, violence, swearing and smoking but never anything about body type or race.

It seems like it's the kneejerk reaction is for people to call comics out for being too sexy or violent or showing subversive behavior, rather than calling them out for not showing things like diversity, or healthy sexuality.

Larson: Yeah, honestly I think it would be awesome if I had an editor that was like, "Could you put in some more fat people? Or Black people?" Because I do try and do that, to include lots of different types.

I've never put down one of your books and felt like you missed the mark on creating realistic, whole people with a variety of backgrounds.

Larson: I feel like it's one of those things that, as a white chick, I have to be thinking about all the time. I was fortune to be married for a long time to somebody who wasn't white. I learned so much from getting to see the world through his eyes, and getting to see how people treated him, and I try to always be aware of the issues people face. I can't lose sight of my own position of privilege as I'm writing.

Riley and Kurtis -- as men working in the industry, do you feel like you have to maintain a different level of awareness about what you're portraying?

Wiebe: Not really. I sometimes worry that in writing a series like "Rat Queens" with four female leads that I'm not being accurate in the way I portray women.

Has there been any backlash on that subject?

Wiebe: Not really. The only thing I've seen is people calling me a femi-nazi, and accusations that I'm writing for the femi-nazi crowd -- which is both laughable and offensive all at the same time. This is an issue, though, because there's this weird elitist aspect to the comics community out there that is still unwelcoming toward women. It's bullshit, it's infuriating, and I'm sure those are the people making comments about me.

I'm writing characters that, in spite of the fantasy setting, I feel are real people. I try to write them as real people with real desires, wants, fears, weaknesses -- and somehow by making them real, people think I'm pandering to a female audience to try and get them to like me?

What about with the merchandise coming out for "Rat Queens," which is geared more toward your female fans? Any complaints there?

Wiebe: Yeah, actually, we got a bit of blowback on that. Some of the guy fans have said, "Don't forget about the male fans!" And I'm like, come on! No one's forgotten about male fans for 70 years! Our female fans have been asking for merchandise, and, sure, you can get shirts made through Image but they're just general one-size shirts that fit one body type.

So I started talking with my fiance and she suggested that we make things specifically for female fans that they feel good wearing, that also fit their body types. It's a very important part of getting to those readers -- not just with the story, but also with giving them things that make them feel comfortable. And its not like it's a marketing thing, it's just a natural part of what we're doing. We saw a demand for it and we're running with it. Who knows, it could totally fail.

What do you think the catalysts will be in creating meaningful change in comics, where people of all body types and genders will be naturally included?

Wiebe: I feel like the emergence of independent comic work is only going to make it better. There is a desire for creators to be genuine without a lot of editorial getting in the way of the true voice behind what they're doing. It's a topic that's being talked about, and female comic readers are coming out of the woodwork now that they have a voice, and that's only going to get stronger. I really do feel that indie publishers like Image and Oni are the ones bringing these books out, helping them become the mainstream, and that's a pretty big factor.

Larson: I think the world is moving in that direction. Maybe that's too optimistic, but kids today and the generation coming up as the next group of comics creators are super-aware of these issues. They're incorporating it into their work because that's what you do as a writer. These kids growing up on the internet, on message boards and Tumblr, having all of these discussions about diversity -- my hope is that it will just continue and self-perpetuate.

Rossmo: Thinking about what Kurtis said earlier, about his male fans -- the haters are always going to hate. The people who are the angriest and the most vocal about stuff, especially on the Internet, are always going to have a voice. I do see some progress, and I hope it gathers momentum. From a business perspective, fans are good. The more fans people have, the better, and the more you cater to those fans, the more money you'll make. So as the fans demand better, the comics industry will have to keep up. The best thing fans can do if they don't agree with books is to not buy them, and to buy the books that are getting it right.