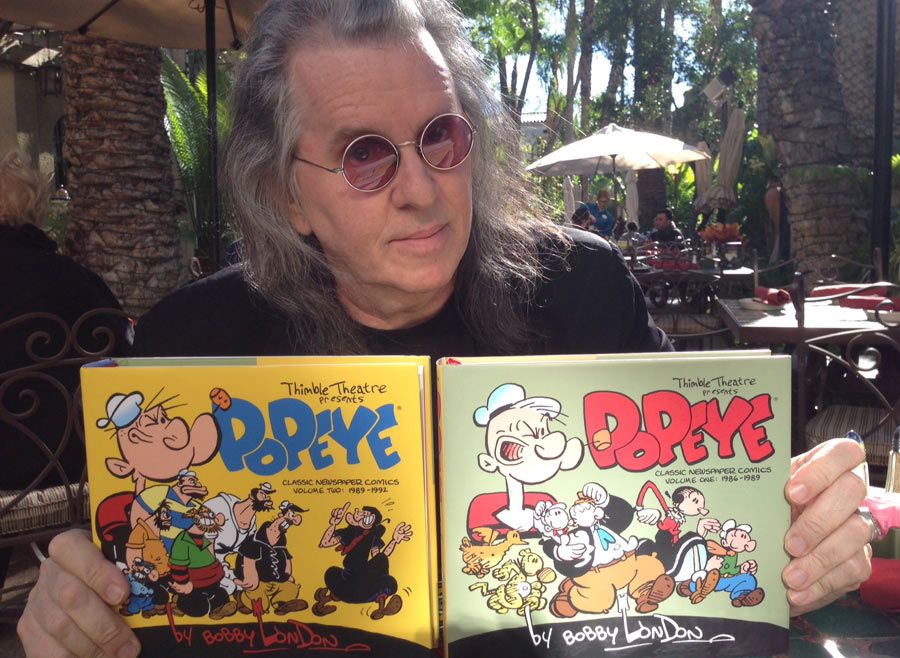

A noted member of the underground movement, and a member of the infamous Air Pirates, cartoonist Bobby London is best known for creating "Dirty Duck," a character he's drawn for more than four decades in the pages of publications including "National Lampoon" and, currently, "Playboy." London was also a contributor to "Nickelodeon Magazine," where his strip "Cody" was a readers' favorite.

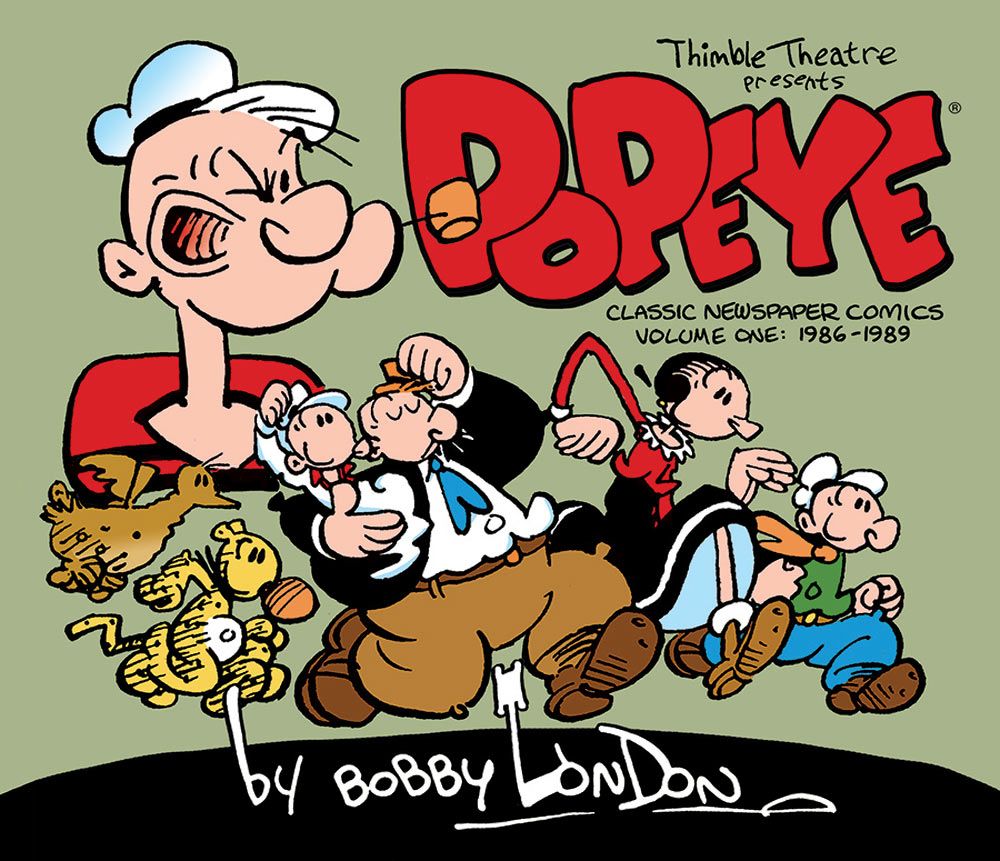

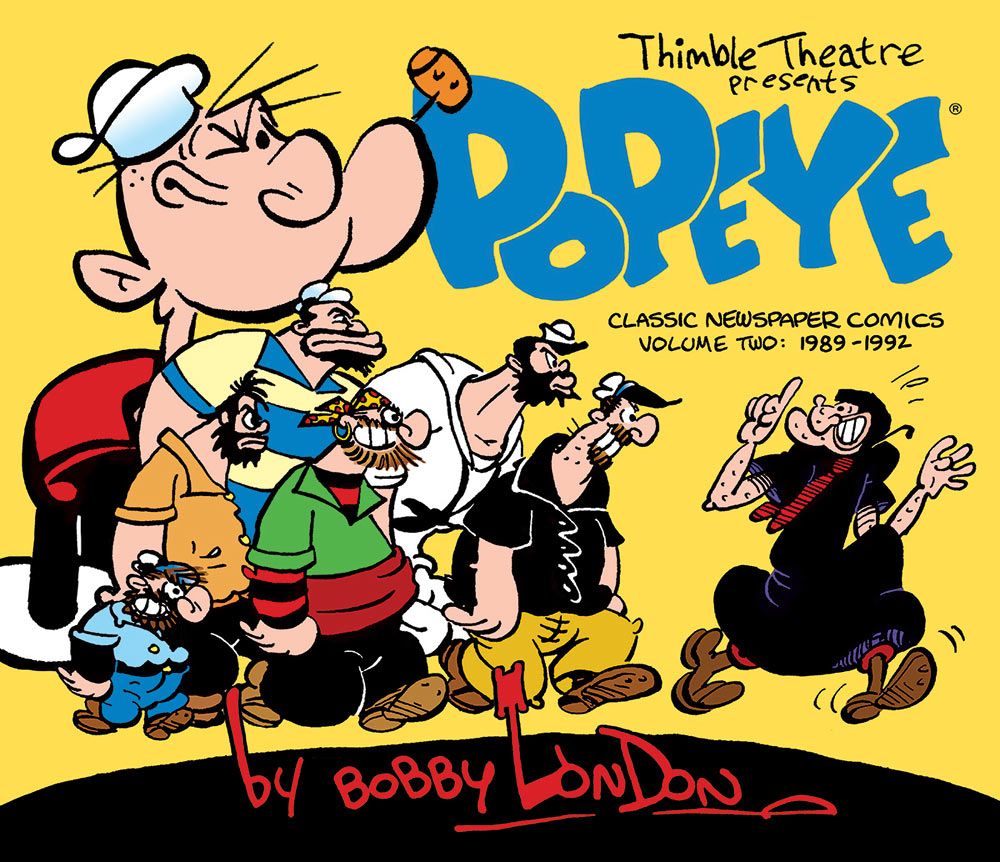

In 1986, London took over the daily, syndicated "Popeye" comic strip from a retiring Bud Sagendorf. A longtime fan of E.C. Segar, London's tenure on the strip ended abruptly in 1992 when he was publicly fired, ostensibly due to "Witch Hunt," a story which touched upon the topic of abortion. But as London explains to CBR News, the problems were far more complicated than that.

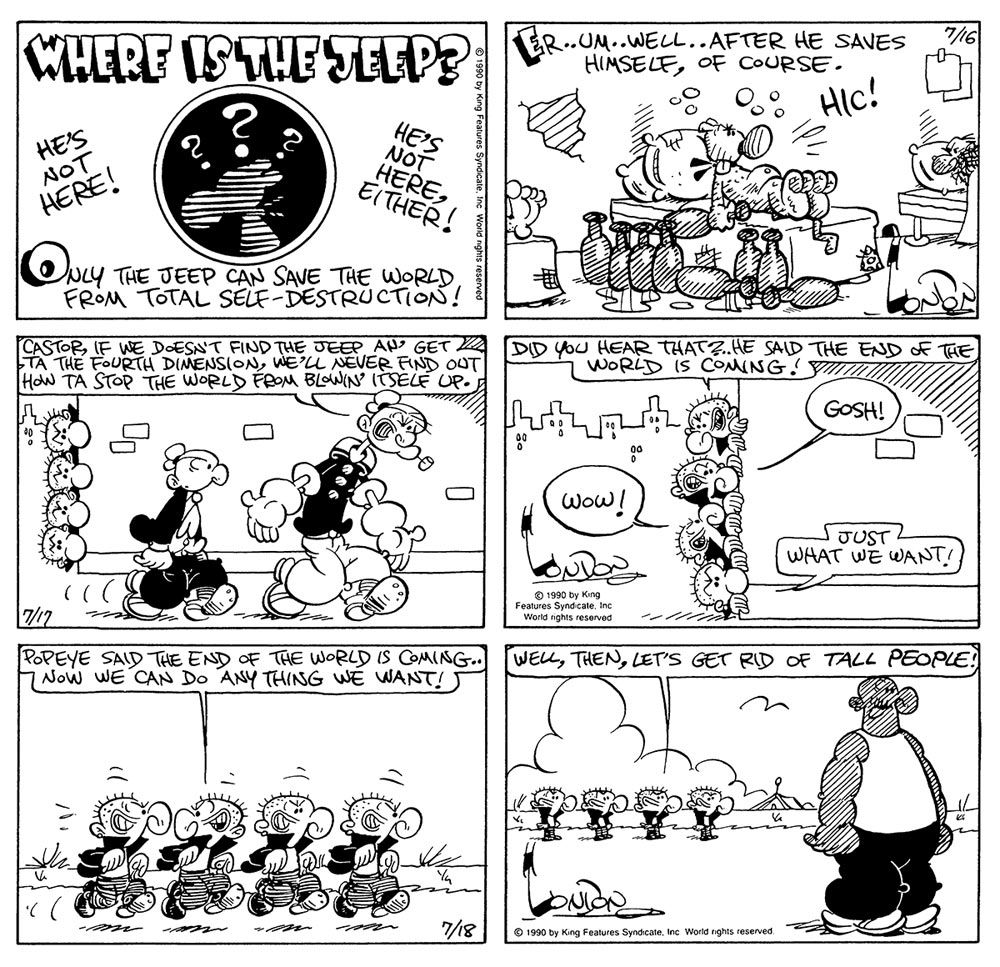

IDW Publishing's Library of American Comics has now released the second of two books collecting London's run on the strip, including those that never saw print, wrapping up his final storyline and his run on the comic. The second book represents London's take on "Popeye" and the result is a beautifully drawn mixture of topicality, reverence and timelessness, features which mark the best comic strips.

CBR News: I've been really excited to read these books because my local papers never carried "Popeye" so I never read these before.

Bobby London: I was very surprised when this book project happened. I bumped into one of the editors from IDW over a year ago, and he asked me what I thought about doing a collection of "Popeye." I said, that'll never happen. He got a very strange look on his face and said, well, think again. [Laughs] I was always under the impression that I would be the Henry Miller of Popeye-dom.

Henry Miller was eventually unbanned, though I would imagine that after being unceremoniously fired as you were, you never expected these strips to be published.

At least I can still eat my spinach.

When you were first approached to take over "Popeye," what was it that interested you about the gig?

I suppose at the time I was as surprised as everybody else, but not for the same reasons. I was well aware that the boilerplate reaction around town would be, "Do they know who that guy is?" You know, the old 'underground monster' thing. But I was surprised that they got it, that they made the connection. I was also pitching my own family strip idea to them and the other syndicates, based on the characters in my "New York Times" illustrations. I got lots of mainstream illustration work when I returned to New York in 1976; thanks, initially, to my original art director from "National Lampoon," Michael Gross. I also got offers to either launch or relaunch licensed character strips -- famous titles -- for big money and turned them all down because they were bad fits.

"Popeye" was another story. I was tapped by "Heavy Metal" magazine in 1980 to illustrate the "Heavy Metal" comic book version of the Robin Williams movie, a script by Jules Feiffer, and no-one to tell me how to draw, but the movie bombed and that was it. I knew all the Westport-area cartoonists, including Bud Sagendorf. When I got the call from Bill Yates, he said, I hear you know all about "Popeye," how about coming down and trying out? You see, they had a problem: They couldn't find anybody who knew all the characters. My first sample was rejected because they looked too much like E.C. Segar. The second was drawn too big and the third was the charm. I was ready to pick it up wherever Sagendorf left off, but somewhere in between tryouts, they told me they were changing it into a gag a day strip and I balked. I didn't see how that could work. Then Yates said Elzie Segar was his instructor in a mail order cartooning course, he and Sagendorf were close friends and he was choosing me because my stuff had "a lot of heart" and he didn't want Popeye to "go the way of all the others." The flinty look in his eye disappeared when he said that, and I thought, okay, maybe I can do this.

So from the beginning, you were thinking about how much the strip should look like Sagendorf and how he drew it, and finding a way to adopt your approach to the rhythm of the strip.

Of course. I had no objections to drawing like Bud Sagendorf. I had spent an afternoon with him and his wife in their home in Waterbury in 1976, and we got along famously. I had a subscription to his Dell comics when I was a kid and was familiar with his writing style. Of course, I had hopes of segueing into my own version eventually but I'm more of a traditionalist than most people think. The one thing I was not prepared for was this gag-a-day thing. "Popeye" is a story strip. The Sunday page was traditionally a gag strip or limited continuity separate from the daily. Easier to market, I understood that, but a gag-a-day "Popeye" daily?

They may have wanted to make "Popeye" a gag-a-day strip, but later you got to make long stories than lasted for months.

I think they were getting bad feedback about their gag-a-day concept and eventually relented. Writing a gag-a-day "Popeye" strip was a total game-changer, I must say. I had to rethink my whole approach fast, and come up with something that would maintain at least a shred of continuity. I remembered my couple of years at Disney Licensing in New York where they would dress Mickey Mouse up as Michael Jackson or have him skateboarding, and all that pseudo hipster stuff, trying to update his image. I thought, what if I lampoon that whole approach with Popeye -- only keep Popeye the same and have the other characters freaking out and trying to keep up with the times? It sounded good to me, and obviously it sounded good to Bill Yates because he okayed it.

I wasn't concerned about the style changing radically, because my drawing style was already in that neighborhood to begin with. However, I had been drawing Disney characters for two years previous to that, so I almost forgot what my own drawing style looked like. It took a while for me to draw like myself again, but it did happen. Many artists' first moments on previously created properties have sometimes been a tad awkward -- however, I have to say that Bela Zaboly's first year on "Popeye" was titanic as far as doing Segar's style was concerned. In the course of my research for that project, I found newspaper clippings of his first year or two and I was just blown away by how perfectly he drew like E.C. Segar from 1939 to say 1942 or so. He even broadened the graphic scope, but he wasn't the writer and poor stories gave him fewer opportunities to expand his art, which I saw before Sagendorf's or Fleischer's.

This second collection felt like you doing "Popeye" in a way that the first didn't. When I say that, beyond the art, you were telling long stories, they were topical, but the strip also had this weird timelessness.

Oh, yes. Timeless stories. Funny how I've been accused of just the opposite, of defiling the sanctity of the strip, of putting it on its ear. Did they realize that I was being pressured to redesign the entire series to look like "Popeye & Son?" And refusing to do so probably cost me my job? I defended the sanctity of that strip, I didn't destroy it. I was twenty years old when I created "Dirty Duck," and I stuck with him because I knew he was this timeless character -- he had one foot in the past, one foot in the present and his butt in the future. That sort of equals timelessness. I knew I could bring that same quality to "Popeye" if I could just overcome all that ill will.

"Popeye" was very much of his time. He talked about the Depression, fascism, unions, gangsters, short skirts, politics. I wanted the average reader to relate to him again. I certainly wasn't afraid to draw a cell phone or ATM machine, because the way I would draw a cell phone or an ATM machine would look exactly like a Popeye version of a cell phone or an ATM machine. He was in good hands because I left him alone. I had him walking around in that same old suit, and the party girls would say, "He's so punk!" There's no difference between what I did and having him fight gum card monsters from the 1950s, but, no -- they hated it. They would rather have had him in a Hawaiian shirt, a baseball cap and little blue shorts. You cannot change Popeye, kids. He is the one constant in an ever-changing universe. His credo is "I yam what I yam, and tha's all that I yam" -- how can he go against his own credo?! Sure, you can put him through costume changes for story purposes, but take away his pipe forever? Even his bloody theme song has a pipe.

Well, they can all rejoice. I'm not in the Popeye business anymore. They can do whatever they want with him now, it's all the same to me. But as long as I was the proprietor of Elzie Segar's newspaper strip, that wasn't gonna happen. Not on my watch. No, sir. And, yes, I know Segar is dead and King Features has owned Popeye for the last 200 years. This article seems to think I was unaware that I was work for hire, which isn't true. After all, I signed Bill Zaboly's contract. Unfortunately, that issue came up when I got in, shall we say, a "dustup" on the post-firing interview trail with a feller from the Chicago Reader who, in spirit if not the letter, accused me, in the final story, of holding all clergymen up to ridicule.

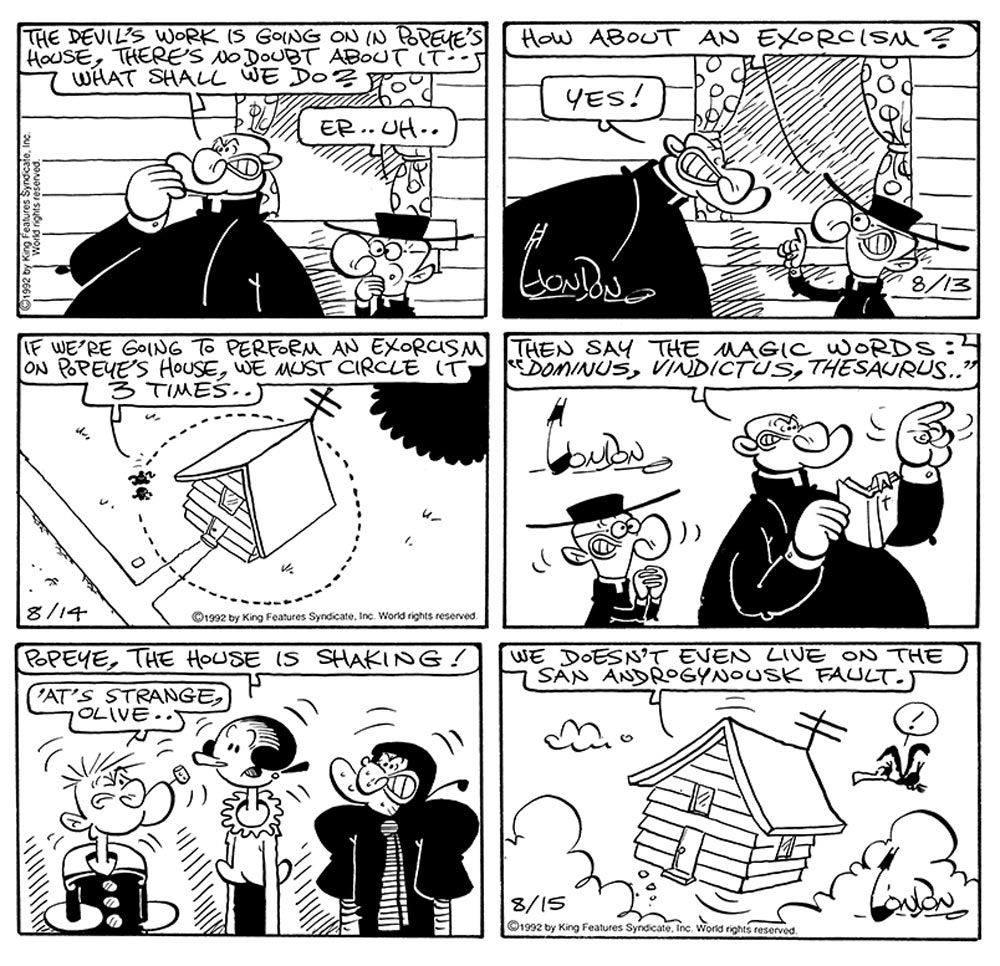

I said I had as much right to draw a clergyman as Doug Marlette. The interviewer disagreed on the grounds that I didn't own my strip, but personally, I thought he was really saying that I, a cartoonist who is not of the Christian faith, had no right to draw clergymen at all. The story was destroyed in mid-stream, and is here in condensed form, so who is anyone to say what I had in mind -- including myself in 1992, battling with a hostile interviewer. Maybe I was shocked to find out not all liberals were my friends.

Regardless of what I said, those priest characters were not villains. The tall priest was the same one administering last rites to Popeye in "Return Of Bluto," so he was definitely not a villain, and at no time and in no place did I depict either of them doing anything villainous. If the big priest was surrounded by sheep in one panel, well, he clearly loved animals in the nicest of ways, and if the "Chicago Reader" thought otherwise, they're the ones with the dirty minds, not me. Okay, my rant is done. Sorry, it's been over twenty years. I had a lot of time to think about it. Now, you kids get off my lawn!

In this second book, you do have one arc where you play with licensing and Popeye's hat, and you really take aim at your bosses.

Ah, yes. "The Stupid Little Hat." The Butoni Macaroni Box hat. Stephen DeStefano's favorite little hat. I adore that story. That was towards the end, when I knew I hadn't much time and I simply had to go there. It was all part of my nefarious little plan.

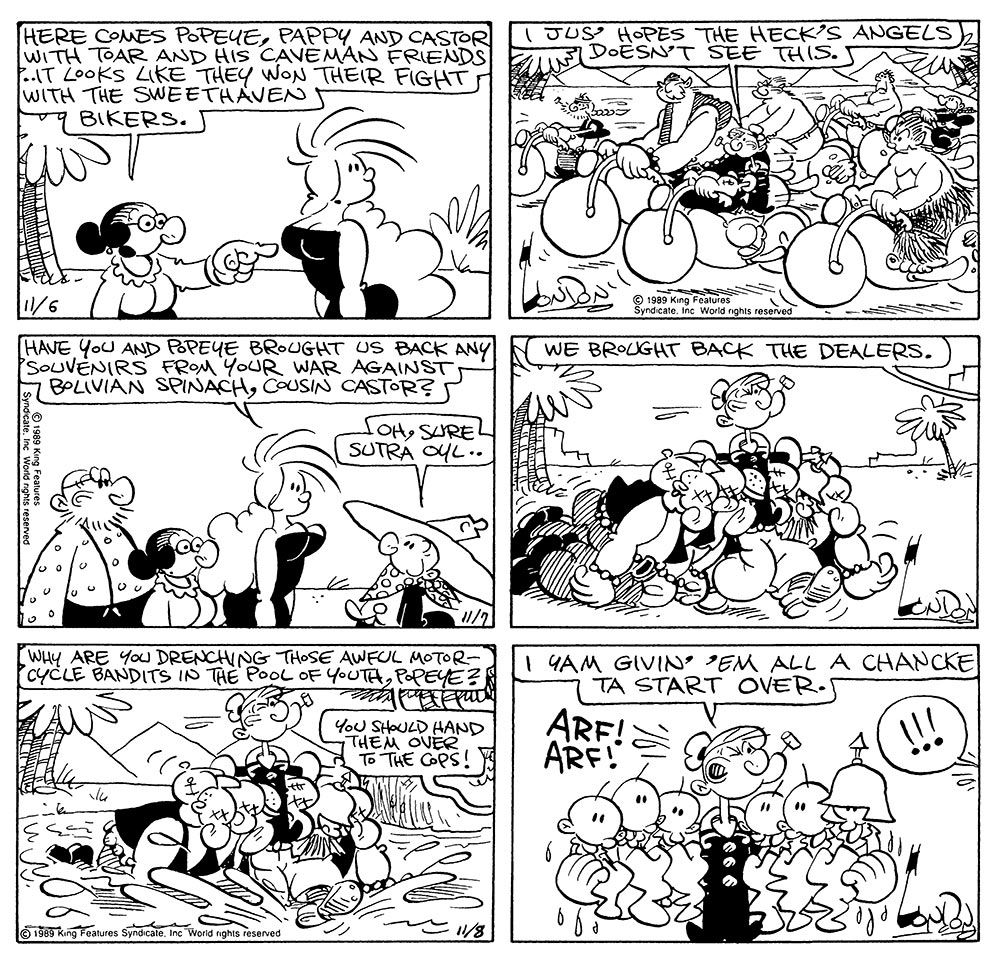

Before those last few stories, though, the stories in the second volume are great. "Heavy Metal Toar" and the Bolivian spinach cartel is hilarious.

I always wanted to do a Spaghetti Western and a motorcycle chase. I love those old Clint Eastwood movies.

That one, the advertising agency story, Popeye's apocalypse, Bluto coming back -- they were great "Popeye" stories, just insane in the best way.

I never thought there would be a best possible way to be insane, but you're very kind. I was told -- just before the final week, I was told that they hated those stories. They said, we hate everything you've been doing for the past six months or whatever. I asked him what he wanted, he said, "Popeye punching Bluto."

There was a three day sequence of Then-President George H.W. Bush dancing.

That was "Oyl Crisis," and Bush was both a desert mirage and an homage to Jules Feiffer. The mythical dictatorship is a Popeye tradition, and I decided to make mine in the Middle East. I was writing it as the Gulf War was unfolding, and it was very challenging. I thought if the war was about oil, then why not have this oil sheik kidnap Olive Oyl and family, because he wants all the oil in the world and Olive and her family are the only Oyls he doesn't have! Uncle Standard Oyl (Castor Oyl in muttonchops, get it?) sends Popeye into this Middle Eastern inferno to save his buddies. I don't know why, but it was one of my favorite stories. The Americans don't come off very well, either, in case you think I was being unfair.

I loved that, but I can also see lots of people scratching their heads at it.

Popeye's mirage of George H.W. Bush in the Arabian desert was a homage to my early role model, Jules Feiffer. It was also one of the first comic strip crossovers, which everybody does today, so what did I do wrong? Nobody had any objections at the time. I didn't hear a thing about it until later.

I also loved Bluto returning and fighting with all the Brutuses.

"The Return of Bluto" was a parable. The original Bluto is actually a stand-in for E.C, Segar. He returns to the strip after decades in exile to find the place almost unrecognizable, overrun with impostors doing his act. Even Popeye is resigned to beating on these dumpy stand-ins day after day. Bluto is morally outraged and the Sea Hag is able to manipulate him into extracting her revenge. It gave me the opportunity to stretch my drawing skills and do all those different versions of Bluto/Brutus: the Famous Studio Brutus, the Gene Deitch Brutus, the George Wildman Brutus, even the Italian Brutus by Sandro Dossi. Every Popeye fan -- and even people who are casual observers of the strip over the years -- have wondered what happened to Bluto? Why was there this name change? I was the first person to formally address this serious social problem in public. By the way, that story was inspired by the 3 Stooges short where Shemp comes down from heaven to reform Moe & Larry. I only refer to the classics.

I love how it causes the town's economy to collapse. It's completely absurd, but it makes perfect sense.

Thank you! The story of my life.

When you started "Witch Hunt," which became the last story, had you had that conversation about how they hated your work, or were there conversations and signs before that where they made it clear that they weren't happy with what you were doing?

I think taking my name off the strip as early as 1990 is a mild indication that they were not amused.

So the problems had been going on for a while, in one way or another, between their complaints and pressures.

The "Popeye" daily died the day they ordered me to make it look like "Popeye & Son."

So with "Witch Hunt" you decided, if this was your last chance to do a "Popeye" story, then go for broke.

Yes. But I was all ready broke so I had nothing to lose.

You wanted to make a story that would be political and push buttons.

No, I was doing it to protect myself. If they really wanted to punish me, they would have kept me on. When I first went up there, I had asked for an option on the Sunday page when Bud retired; they told me that if I behaved and proved my worth, I would get it over time. That was the promise my first editor had made to me; when I brought the subject up again five years later, the second editor reneged on that promise, in a very insulting and passive-aggressive fashion, I might add. I was stunned and I didn't know what to do at first, so I did nothing for a long time. People who really know me know that deep down inside, I'm an honorable person who's as good as his word, depending upon what that word is, of course; but their promise had been broken and all bets were off, so I wrote the "Stupid Little Hat" story. When they called and said stop writing stuff about a licensing execs and go back to Popeye punching Bluto, I said, okay, I promise I wont write about the licensing guy anymore -- then I turned around and wrote "Witch Hunt." The rest you know.

Years later, I read somewhere online that they had no intention of ever giving me the Sunday -- that they promised it to Hy Eisman before they even hired me, so my instincts were correct. To stay on board after all those years of hard work and not be chosen to draw the Sunday page would have been far more humiliating to me than getting fired on a slow news day and being all over the media for 24 hours. And, then, of course, there were the financial losses being denied the Sunday page.

The last batch of strips that were never published and people are seeing here for the first time, you wrap up "Witch Hunt" and ending like you did with Jeep saying goodbye, did you know that would be your last strip?

Well, sure. Of course. I had already been dismissed, and they said you have four more weeks to fill out, so I knew they would be my last strips. I wrapped up the Roe v. Wade story as best as I could according to my original outline and said my goodbyes. Those strips were flatly rejected, and they've been sitting in my files ever since.

I'm sorry. They fired you -- publicly -- and then said you're still under contract for four more weeks of strips?

Yes. They fired me and said, oh by the way, you have four more weeks of your contract to fill out, and you're gonna do these strips whether you like or not.

[Laughs] And then they rejected those strips, which they made you draw.

Yes, Kafka-esque, ain't it? I said, so what? You already fired me! What are you going to do, fire me again? [Laughs]

I'm laughing because it's a different experience from most of us who have been fired or laid off.

I've been through worse. At least it makes for a very nice book.

It does. The book reads well and it ends nicely. Looking back at the strips, 20-25 years later, how do you feel about the work?

I think they hold up great. It really doesn't matter if people don't remember who Milli Vanilli was. I mean, so what? Go look it up. For every Milli Vanilli reference in there, there's a Pete Townsend or Willie Nelson reference. Those people are forever! If Harpo Marx can be in a Popeye cartoon, why not The Beatles? I guess I knew that there wouldn't be a Mount Rushmore-type monument to poor Milli Vanilli anytime soon, but I was trying to be absurd. I try to go for the absurd as much as I can -- the same way Segar did. The way Stan Laurel did! Like Cervantes! Jonathan Swift! Rabelais! Willy Elder!

When I first took the cartoon on, there were people who said, who do you think you are? E.C. Segar created what is arguably one of the greatest comic strips in the history of newspapers. Who do you think you are to try to top him? Well, I know who I am -- at least part of the time -- and I wasn't trying to top E.C. Segar. I figured the only way I was going to get through it was to be myself. And may I say, I got as close to the original with that final story as anything I'd ever written by being myself. I think they proved they'd have fired E.C. Segar if they had half the chance. When you consider the lengths the Reagan Administration went to in those days to to demonize liberals in the media, and the unfortunate results on the evening news for even children to see, my little cartoon story had the Lubitsch Touch by comparison. All of it, from start to finish, was first rate. I have no regrets and clearly, neither does King Features, otherwise they wouldn't have published it all in two delightful volumes. Of course, they had twenty years to think it over.

You've had some strange experiences as a cartoonist, and you'd been working as an artist for many years by that point, but after being fired like that, was it hard to get back into things and draw again?

No, I kept drawing all the way through it. I drew myself getting kicked out of King Features for "Time Magazine," and I was back drawing for the Op-Ed page of "The New York Times." The publicity got me a lot of offers. My friends at Disney gave me work. My face was on television, so people recognized me in restaurants for a while. I became a gym rat, working out three days a week. But my mother was sick, she went into a rapid decline not long after that, and I spent most of my time looking after her in her last days. When that was over, I went back to work full time. I called the offices of MTV and they said come on up -- we don't have anything for you, but maybe someone else does. Chris Duffy, who was comics editor of "Nickelodeon Magazine," picked up a family strip I originally created when I was 12. I had used the characters in my "New York Times" illustrations, but the strip version had been rejected by the syndicates long before and then immediately after I did "Popeye." Chris Duffy and the editors of "Nickelodeon Magazine" liked it and ran it on a fairly regular basis until they ceased publication a few years ago.

That would have been "Cody." Is there a chance we'll see a collection of the strip?

I don't think there are enough pages for a collection, but I might be up for drawing new episodes. Chris Duffy was my editor on "Fairy Tale Comics," most recently. I had three pages where I adapted a Grimm Brothers fairy tale. All it really takes in this business is an editor who believes in you and has faith in what you can do. Chris Duffy was one of those people.

Is there a chance that we'll see a new collection of "Dirty Duck" or some of your other work one of these years?

If you don't, you'll know who to blame.

What are you doing now?

Well, as you know, in 2000, I went West, young man, and drew storyboards for Cartoon Network and character concepts for the first Spongebob movie. It was cool with all of those generous, open-minded folks in Hollywood for me to do that between "Dirty Duck" strips and "Nickelodeon Magazine" assignments. Unfortunately, one particular producer at Disney chose to pressure me to quit "Playboy" before I could work on his show. That would have meant quitting my own characters, and I just couldn't do it. I've been with "Playboy" since 1976. It was funny how there were other comic book artists they didn't ask that of.

People have issues with "Playboy" for many reasons, but I've hard a lot of very good things from cartoonists over the years. Obviously, people like Harvey Kurtzman and others worked there, Gahan Wilson has had a great working relationship with the magazine, and Jules Feiffer called Hefner one of the smartest editors of comics he's encountered.

Hefner saved the "Dirty Duck" strip from an ignoble fate back in the 1970s, so I'll always be thankful to him for that. The blogs say he left me "high and dry" during the Reagan Era, but that's simply not the case. They offered me a full page but I took a half. It was my decision. I'm just amazed at the things people say. About ten years ago, they had a general manager who wanted to get rid of all the cartoons and make it look more like "Maxim." They fired him pretty quickly. They chose their artists over a suit. I couldn't well leave them after that. I don't understand the problems that people have with "Playboy" at all, and I don't want to get into first amendment issues, okay? I don't wage wars, I draw funny pictures.