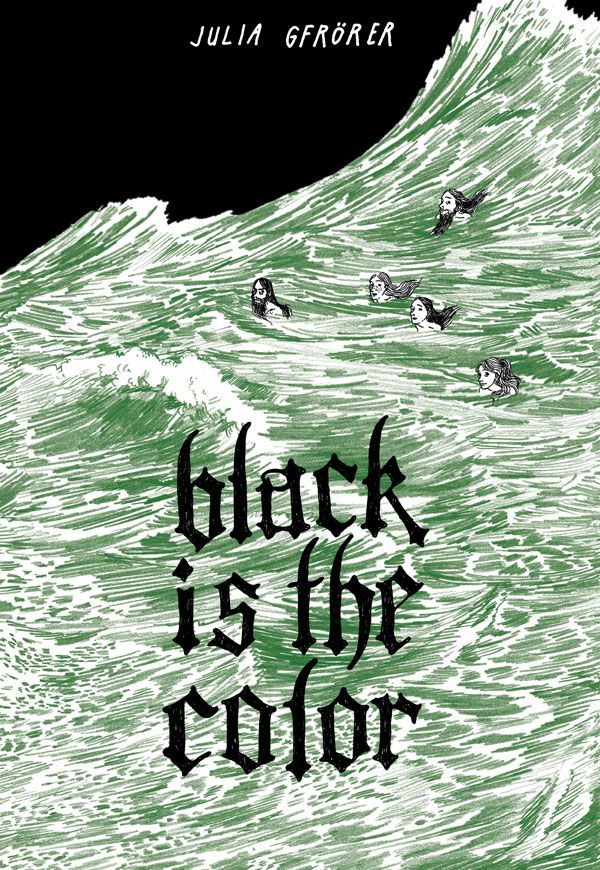

Julia Gfrörer has been making mincomics and posting comics online for many years, with work including "Black Light" and the acclaimed "Too Dark To See." She's won fans in many circles because of her horrific non-horror comics. Gfrörer's stories are atmospheric and often supernatural, but she doesn't depict monsters -- rather, her comics deal with emotional agonies, depicted with elegant linework and haunting imagery.

Gfrörer's new book, "Black is the Color," centers on a group of sailors on a doomed voyage and a group of mermaids. With scenes that could be equally real or fantasy, "Black is the Color" also includes a ghost, pain and death with a resulted haunting tale that, like the best stories, stays with the reader long after its conclusion.

CBR News spoke with Gfrörer about her experience in comics, the ideas behind "Black is the Color," the dark nature of her work, the differentiation between her work and traditional horror comics, and more.

CBR: Julia, while you've published many minicomics in the past, "Black is the Color" is your first full-length graphic novel. Where did the concept begin when developing the story?

Julia Gfrörer: Three years ago, my marriage ended suddenly, and a couple of weeks after that I was laid off from my full-time job. That dispassionate condolence speech felt like a death sentence. I took my infant son on a long-weekend camping trip to the Oregon coast, and I read "The Descent into Maelstrom" and "The Premature Burial" and "The Imp of the Perverse," and I listened to "Ocean Songs" and "The Sea and the Bells." I stood on the beach and felt that impulse you sometimes feel there, the longing to give up and be smashed and torn apart, and at all other times I adopted this wry, resigned apathy, and "Black is the Color" assembled itself in my brain from those things. It started with just the sailors, I wrote all the sailor scenes and then I was like, "Sure, mermaids too. Why the fuck not?"

One of the comments often made about your work is that it's dark. Do you think of your work that way?

It's certainly occult, in the sense that it mines extensively from whatever shadows I myself contain. Almost anything that inspires in me strong feelings of discomfort, my instinct is to dig around in that abscess and yank on the nerves. I go looking for exceptions to every deeply-held moral principle; I try to justify the things I consider reprehensible and to subvert those that are laudable, until I get to a place where every answer makes me equally uneasy, and that's what I write about. When I start to think I've written something that might make me too vulnerable, that's so painful I hate to talk about it, that I'm ashamed to let other people see, I tell myself that means I should stick with it. I have a lot of bad habits that involve damaging myself for comfort.

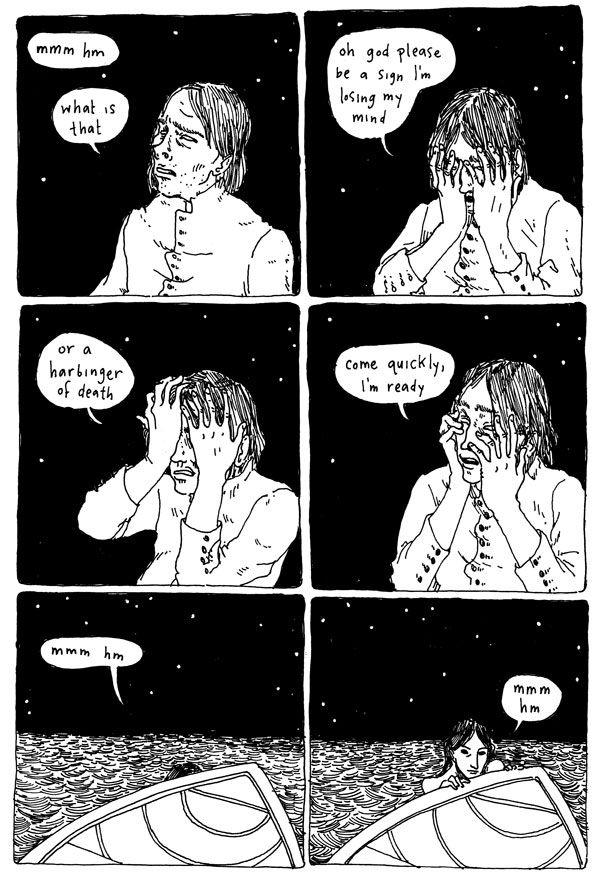

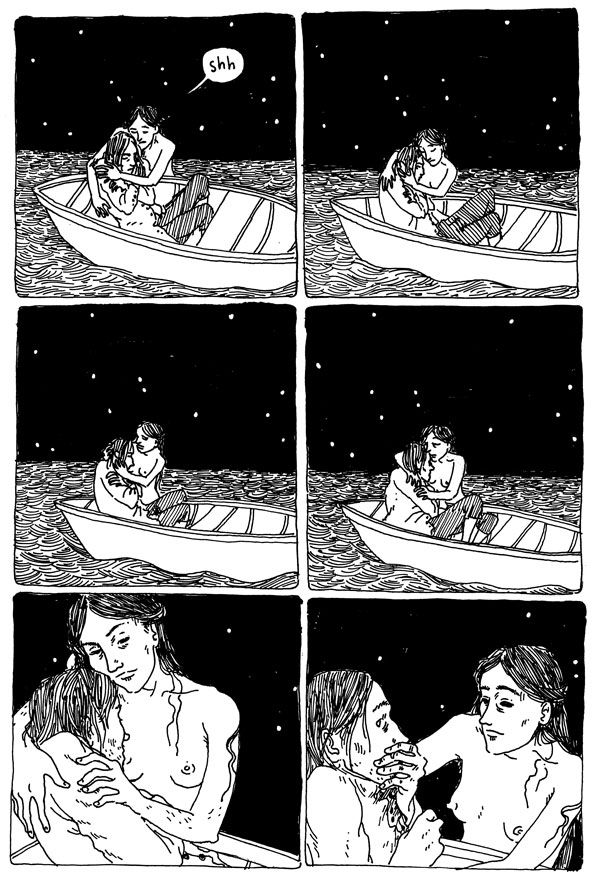

Yes, the work seems dark to me, although the extent to which other people will also find it so I feel unqualified to predict. Certainly it's always gratifying to learn that my demons are also tormenting other people. But I don't intend my stories to be cruel or sadistic, it's not torture porn. I don't want to take cheap shots at anybody or plough blindly through a minefield just for the sake of detonating something. For what it's worth, every type of pain depicted in my work has been extensively alpha tested in my personal life, and the comics serve a therapeutic purpose.

Considering the darker nature of your work, do you think of yourself as a horror creator?

Possibly the relationship of my work to horror is similar to the relationship of post rock to rock music, in that I make use of a lot of the traditional instruments and structures of the genre, but my intent is to create something more textured and exploratory, less goal-oriented, more humane. I find my own work frightening, and I like when people call it "horror," but my stories tend to be anchored more by sadness than by terror. To the extent that I'm interested in conjuring emotions in the "fear" genre, I like creeping dread, contempt, self-directed disgust, the compulsion to extinguish oneself, a crushing sense of futility. I like those moments when you seem to perceive the world with perfect rational clarity and precision, and you see it for the black, remorseless chasm that it is. They might be more accurately called "tragedy" comics than "horror" comics.

Apparently there's a little cohort of alt comics artists mining this emotional vein at the moment, Rob Clough recently dubbed us the Coal Mine School.

I'm really interested in how you use the supernatural in your work, "Black is the Color" included. So much of the time, it's unclear whether the mermaid is real or a hallucination/dream, for example. Are you conscious of planning that and making sure it could be read as happening or just being fantastic and thinking about the ways people can read aspects of it?

I guess this is an issue I leave intentionally unresolved. Possibly too much credulity or certainty, too much precious world-building of any kind would ruin the entire enterprise for me. So there are no tedious origin stories ("at the dawn of time the first teenage boy had his very first wet dream and that's how the succubus was born"), and none of those smug resumes of supernatural abilities ("Don't be silly, garlic is harmless! But yes, I am condemned to eternal living death"), and also no big reveals to restore the established order ("the entire town was high on hallucinogenic gas all along, and none of this really happened"). As both a reader and a fiction writer I tend to be strongly explanation-averse. (In a non-fiction context I'm a tireless explainer, QED.)

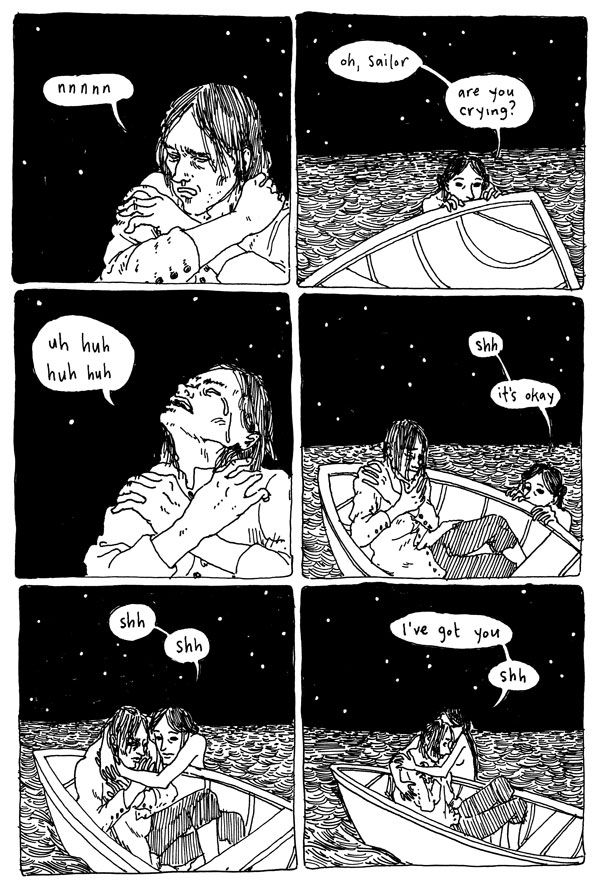

In my minicomic "Too Dark to See," uncertainty about whether the supernatural characters are actually present is part of the machinery of the story. A succubus and an incubus seem to embody the discord creeping into the home of a young couple in love, and it's difficult to know for sure whether the problems are real, whether the monsters are real, and which of those factors first conjured the other. On the other hand, the mermaids in "Black is the Color" are shown doing things-watching a ship sink, catching lobsters, planning experimental music projects-unobserved by the human characters, so I guess that means they're real enough and not the hallucination of another character. I don't know about the ghost, though. Might be. I mean, what is real. It's a novel. None of it is real.

In another sense you also like to play with the quotidian and the fantastic: like the mermaids watching the ship sink and their conversation. At what point were you thinking about, how to present them and what should they do and contrast it with the events happening?

The jeering tone that dominates the speech of the mermaid characters throughout the book is a response to the more traditional depiction of mermaids as playful or seductive. "The Little Mermaid" specifically describes the mermaid sisters calling invitingly to sailors on a sinking ship, somehow unaware (though the main character realizes it later) that the men are in danger. My mermaids were a little more astute, so their flirtation has conscious overtones of cruelty. When writing supernatural characters it's important to me to show that they don't think of themselves or the events of the story as exceptional-the human characters behave with extremity because they're usually experiencing the most painful events of their lives, whereas to the supernatural characters it's all more or less normal, and they're relatively flippant as a result.

You have a lot of panels and pages of the ship, the sea, the sky. How much did that shape the story?

I don't dislike drawing the sea and the sky (though I struggled a lot with the ship), but the real reason I included those things was that it was important to me to create a sense of loneliness, of both spatial and temporal infinitude, of boredom, and then also within Warren's confined space an irreconcilable claustrophobia. My stories are shaped less by what I get pleasure from the physical process of drawing, or from looking at, and more by what I get pleasure from dwelling on emotionally, as a philosophical exercise. And I like to think about despair, I like to think about helplessness, I like to think about things that are big enough to crush me, so I was drawing this vast landscape again and again to evoke those feelings.

Mermaids and dripping black liquid appear frequently in my automatic drawings, so I guess that means I enjoy drawing them. I did try, though, (I don't know how successfully) not to make the mermaids too pretty or seductive. They're supposed to be monsters. I, too, have been mistaken for seductive when I was in fact monstrous.

Where did the title for "Black is the Color" come from?

It's a folk song. Here's Nina Simone's very moving rendition featuring Emile Latimer. I like this version by the Espers, too. I chose it because it's a sad love song, it's a song about longing, and in particular the line "I love the ground whereon s/he stands" was very affecting to me when I considered it in the context of a love story where certain characters are bound by the sea. Removing the title from the context of the rest of the lyrics, the color black itself plays a role in the book, and darkness also tends to have redemptive power in my work.

Are there any plans for a collection of your short comics?

You know, a lot of my pocket notebooks contain little running tallies of the exact number of pages of comics I've completed over the course of my career, and if you exclude "Flesh and Bone" (addenda to which I still occasionally write, though haven't drawn yet, and therefore I don't consider it completed) and "Black is the Color" (since it's already been published as a stand-alone graphic novel), I don't think it comes to even a hundred pages. I self-published two new minis this year ("Black Light" and "In Pace Requiescat") and I'd like to a couple more for next year, and maybe after that I'll have enough material to start thinking about a collection.

"Black is the Color" is now available from Fantagraphics.