Oyster War cartoonist Ben Towle posted an interesting consideration this week about how we discuss comics, and the tendency to rely on film terminology. From scripts to reviews to casual exchanges, we often rely on film language, referring to a panel composition as a "shot" or "camera angle," for instance, despite the vast majority of comics never employing cameras (fumettis not withstanding). By Towle's own admission, the post is a collection of disorderly thoughts, but it encourages an examination of how we think and talk about comics, and how we make them.

His "Let's Stop Using Film Terminology to Talk About Comics" is likely to elicit responses like "I'll use whatever terminology I want" and "What difference does it make?" That first reaction is of course true: We can all use whatever terminology we like. A blog post isn't going to change that, and certainly the ubiquity of film won't prevent its terminology being used in the context of comics from being understood. However, the answer to the second response might cause someone to reconsider that first. As Towle explains early on, how we talk about something affects how we think about it. It's why politicians are so careful in the terms they use to describe opponents and allies. They're hoping to establish terminology for a group of people, which in turn influences how we think about them as well. Is someone receiving welfare relief or government hand-outs? Was information obtained from prisoners or detainees, and were torture or extreme-interrogation techniques used? Obviously those are very politically charged examples, but to bring it closer to home, there's a reason the term "graphic novel" was promoted over "comic book" to bookstores and other mainstream outlets. Words not only have meanings, but also connotations; they can imply judgment, status, and much more. They influence how we perceive the subject of discussion and how we're likely to think of it in the future. So yes, it does make a difference.

The real question is, "Do I care what difference it makes?" I hope the answer is "yes," and here's why: If we predominantly think of comics in terms of film and film terminology, then we're eventually only thinking in terms of how comics can reproduce what film does. Comics are a powerful medium, and my favorite one, but I have news: Comics can't do what film does. That's good news, however, because comics don't need to do what film does; film already does it just fine. A comic shouldn't aim to be nothing more than an unproduced movie. There are certainly plenty of comics that are just that and little more, and usually those instances are obvious and fairly uninspired. But there's no reason comics should settle for that. Comics get to do what only comics do. Film and comics speak different languages. Like French, Spanish and other Romance languages, there are commonalities, shared traits. But there are also distinct differences.

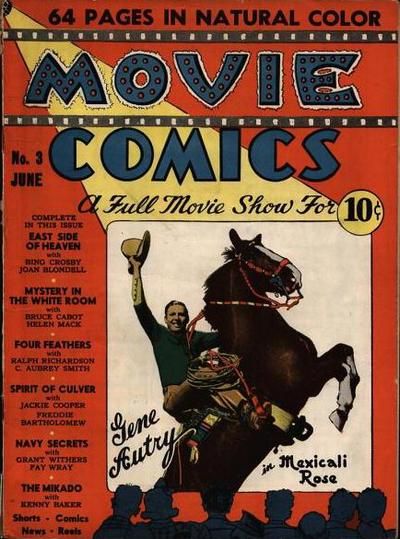

The shared languages come from their shared starting point, as far as how they composed their respective shots and panels. Theater, and particularly vaudeville shows of the late 1800s and early 1900s, were the dominant source of entertainment when comics and film began. Initially, both newspaper comic strips and silent films shared a similar composition style that essentially recreated the audience's point of view in theater: a static, eye-level perspective looking at the full figure of each character. Of course, there is plenty of evidence to suggest that comics predate these early days by centuries. Even those proto-comics share a similar composition style, which is reflected in a lot of the contemporary art in Egypt, France and elsewhere. As Towle points out, this more limited depiction is also generally used by children in their drawings, not by choice but because they aren't yet able to manipulate perspective in their minds and reproduce it on a page. Shifting perspective, cutting to different scenes and other techniques now completely taken for granted were developed through experimentation in both film and comics. Which made what developments first is hard to say, but it's clear at least some practitioners of each discipline were paying attention to each other early on. Comic strips like The Katzenjammer Kids and Alley Sloper were among the first comics adapted into film in the late 1890s. The Happy Hooligan short films were extremely faithful adaptations of Frederick Burr Opper's strip of the same name, carefully attempting to recreate the look of the characters and the slapstick comedy. A few decades later, Walt Disney Studios repurposed the comics form into storyboards, a technique to plan camera angles for an animated movie in 1933. Eventually, that pre-production step became an industry standard.

But the mutual admiration wouldn't last. The '50s gutted the comic book industry and soured public perception to the art form, although comic strips somehow sidestepped any association. Meanwhile, Hollywood went through several booms. Film along with television, which shares nearly identical terminology, became the dominant form of entertainment in America and much of the Western world. While comics predated, and even helped to shape, film, they no longer mattered in modern discourse. Comics themselves seemed to admit defeat with stories frequently borrowing popular movie titles.

Despite that, others in comics experimented with form and function, and we came to realize the art form really had its own language: the shape of panels and how they relate to other panels on the same page while presenting a fluid narrative between them; the ability to read a moment of a story yet also see the before and after on the rest of the page; playing with time through the use of space; the effect of fonts and styles of words on the story and how they react and respond to the art around them. Those are things film cannot do. There's so much more, as we continue to discover. Largely these discoveries happen because those creators weren't thinking about their panels as camera angles. They realized comics are their own thing.

Today, comics' influence on Hollywood and beyond is unmistakable. Between the nadir of post-'50s self-exile to now, there have been a number of creators who have helped establish, or re-establish, comics terminology; there's no longer any reason to rely on film. Influences come from all kinds of sources, so that's not to say that comics can't use film and film elements in their creation, but not to the exclusion of theater, music, literature or any other experience that shapes what we create and how we see things. Comics are great enough to stand on their own.