Be afraid. Be very afraid. This spring, one of writer/director David Cronenberg's most disturbing, gory and disgusting films of all time gets a comic book sequel.

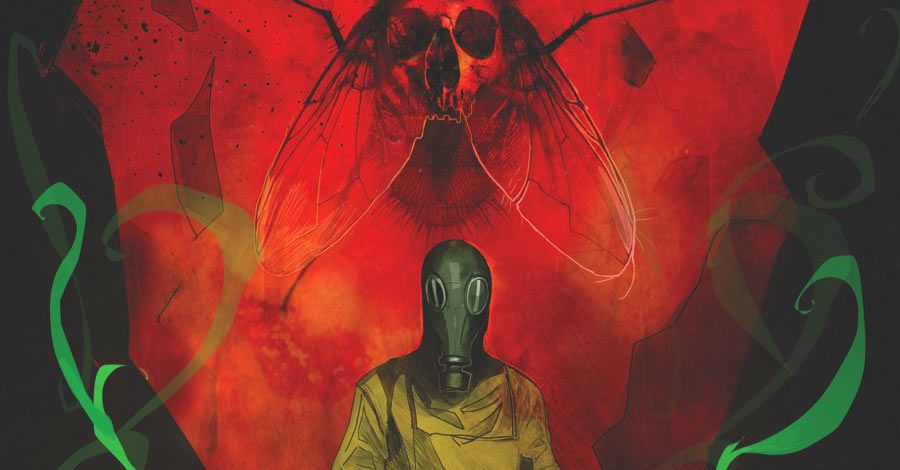

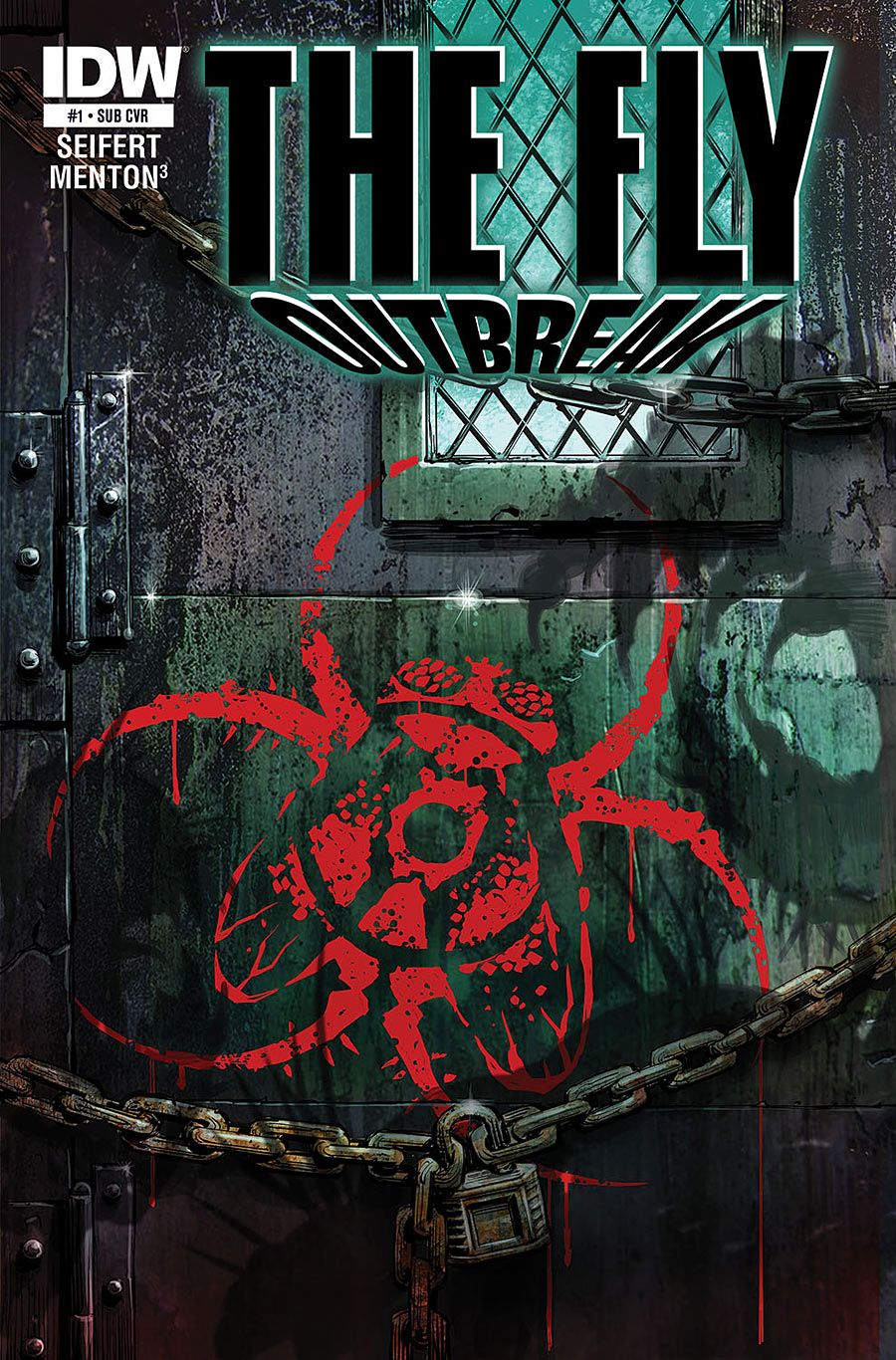

"The Fly: Outbreak," by "Witch Doctor" writer Brandon Seifert and "Monocyte" artist menton3, picks up where from 1986's "The Fly" and its 1989 sequel left off, following mutated scientist Seth Brundle's son Martin as he attempts to stop a genetic plague from transforming the human race into transgenic insects.

And don't think for a second that the fact that neither Seifert nor Menton consider themselves "horror guys" they won't crank up the body horror in the IDW Publishing-released series. In fact, Seifert told CBR News he conducted research with a friend who genetically modifies organisms for a living, just to make sure he got the science of "Outbreak's" horror as right as possible.

CBR News: As this is a sequel to a well-known project, where does it pick up? How does it fit in with the previously established mythology?

Brandon Seifert: "The Fly: Outbreak" is a comic sequel to 1986's "The Fly" by David Cronenberg with Jeff Goldblum. It's also a sequel to the 1989 film "The Fly 2." It's set a few years later and follows the characters from "The Fly 2," including Seth Brundle's son Martin, who inherited his father's transgenic insect gene. During "The Fly 2," Martin was able to cure himself -- but at a cost.

We pick up with Martin trying to pay back the debt he accrued at the end of "The Fly 2." Although his intentions are good, he ends up basically creating an outbreak scenario with this transgenic fly infection that started with his father. Our story is Martin and everybody else trying to deal with that and keep it from becoming a global plague.

Considering it is not nearly as beloved or revered as the original film, why did you decide to use "The Fly 2" as your jumping off point?

Seifert: The sequel certainly isn't the classic that the first one is, but I find it a much more interesting launching point for a modern day take on "The Fly." There are not so many options for picking up the story of the original film other than the direction that they took in the second movie, which introduced Seth Brundle's kid. The second one is certainly not as good as the first -- but I saw a lot more storytelling opportunities picking up after it.

Menton3: Obviously, the original was a lot better, but I'm a big fan of Eric Stoltz, and the sequel was one of his first big roles. I thought [the sequel had] good storytelling, but the directing was kind of bad. For the year it came out, though, it wasn't all that bad. But it doesn't stand up as a classic. The first "Fly" is a classic.

The original "Fly" is extremely famous for its violent and graphic "body horror." Are you fans of that particular horror subgenre? Will we see those themes reappear in "Outbreak?"

Menton3: You know, they're giving me some freedom with the monster that's getting created. I want to do the story justice and make sure I'm getting the right emotion with the monster. If it comes off as body horror, then great, but it's not something I feel I need to do and if I don't people will be upset. I'm just doing what the scripts are calling for, and going for the mood that Brandon and [editor] Denton [Tipton] want. But there's a lot of gross stuff, for sure.

Seifert: On my end, I'm certainly trying to stay true to the body horror element of the original movie. But one of the things that most occurred to me when doing a modern day revisiting of the Cronenberg film was that ["The Fly"] was an effective allegory for the disease scare of the time. Cronenberg said it wasn't intended that way, but a lot of people thought that it was very metaphorical for the HIV/AIDS outbreak of the '80s. I find that really interesting, especially in the context of doing a modern version because we are so afraid of infectious diseases and epidemics and pandemics at this point, but they're all very, very different from HIV. Things like Ebola, swine flu, SARS, antibiotic resistant bacteria, all these different things. Very few of them are spread sexually, so they're very different [from HIV/AIDS]. The core is the same, but the exterior is very different. So one of the focuses I've done involves both the body horror of your body betraying you and mutating and transforming and getting sick, but then also involving other scary parts of infectious disease like the fear that people around you might be infected and might infect you, too. In different issues, we focus on different kinds of horror.

Really? How will that work?

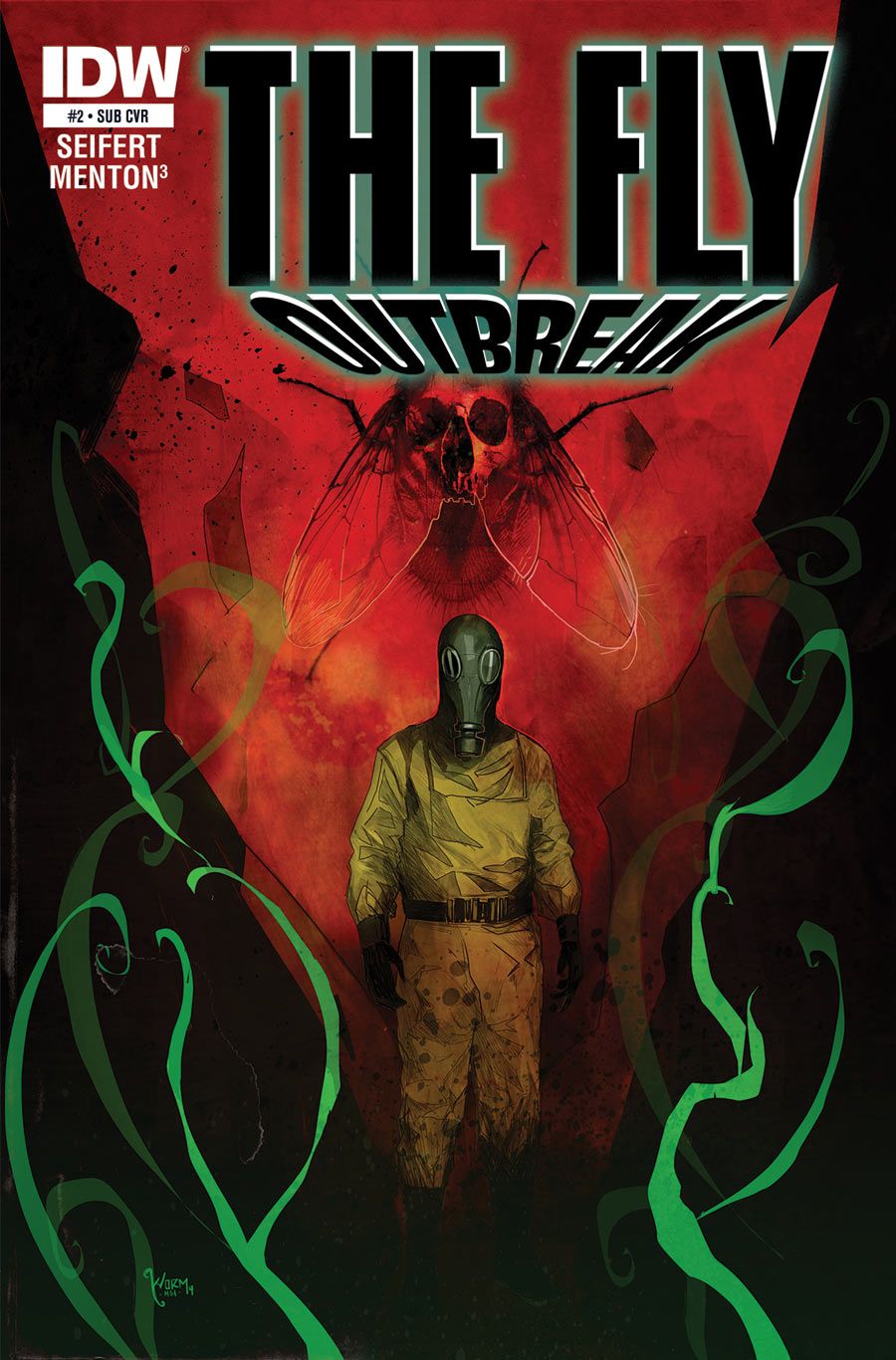

Seifert: Well, Issue #2 is about these people who have been exposed to this infection and have eventually caught it. They're quarantined to get them away from the general public until government scientists can determine whether or not they're really infected. We focus on the quarantine and the kind of paranoia that comes with wondering if your friends and loved ones are going to infect you with an infectious disease that's going to kill you. That's a big element. It's more like John Carpenter's "The Thing" kind of fear rather than body horror. And then we go full on into the body horror from there.

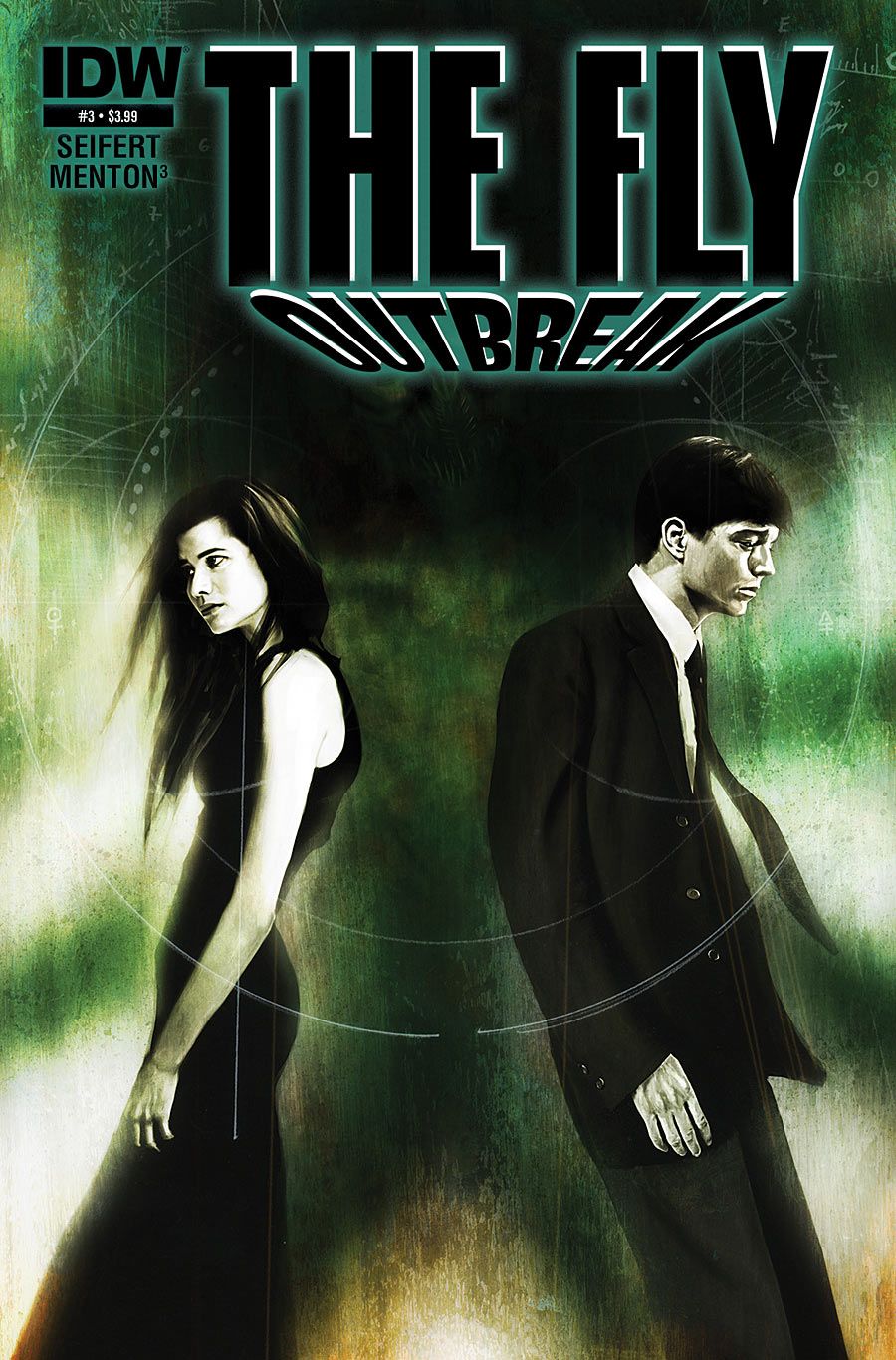

Starting in Issue #3, we find out who is infected and who is not. The people who are infected begin to really show signs of the disease, and it gets much more into the horror of mutation and de-evolution. Becoming less human.

Menton, are you trying any new art styles or techniques with "Outbreak?"

Menton3: I always try to change up the style of every book I do. I always try to do different stuff, and this one is no exception. I'm trying to do a lot more line art, which is not easy for me to do. At all. Traditional comic stuff is not easy for me. So I've been trying to do that more. When it comes to the monsters, I'm trying to get those fully rendered and make them a much different reality than the people around them.

Menton, your "Monocyte" had some pretty disturbing stuff, and Brandon's "Witch Doctor" definitely has a horror bent to it. Do you consider yourself horror guys? Do you set out to get these assignments or does it just sort of happen that way?

Menton3: I was shocked and surprised that people thought my art was horror-based. I've always been like, "Really? Ok, cool!" It sounds kind of cheesy, like I'm some old lady who collects cats and listens to Tori Amos all day, but I meditate and then I paint and draw what I see in my mediations. That's for my own personal artwork, for gallery work. When it comes to comics, I also keep some of that influence. I spend a lot of time doing that, and to me the art is beautiful, not dark, so it's always a surprise to me when people tell me I'm a horror artist. I had absolutely no idea! But I enjoy the genre and I enjoy being associated with the genre. I watch a lot of horror movies, but I wouldn't consider myself a horror artist at all. I just kind of do that a lot. You mention "Monocyte," which people view as a horror book, but I don't.

Seifert: It's interesting that you feel that way. We've never had a conversation about this before, but I'm also in the exact same position. I love horror, but with a lot of people who love horror that's their thing. They love horror, and they don't love anything else remotely as close. You get a lot of horror writers and artists who are much more interested in doing horror than anything else.

I am completely not at all like that. I enjoy doing horror, and I want to keep doing it, but there are so many other things I love and want to do, too. I think that's reflected in my horror-based projects. There are a lot of other influences that end up included in it. With "Witch Doctor," I always feel it's a harder science-fiction story masquerading as a supernatural horror story. With "Outbreak," it's a horror story, but it's also very, very much a science-fiction story. I'm approaching it from the science-fiction angle. It's one of the things I'm most excited about.

Menton3: It's strange -- I've been asked in interviews, 'What do you consider to be horror?' and a lot of stuff other people consider to be horror I don't think of as even remotely scary. I never remotely thought Freddy Krueger was scary. I thought he was like a superhero. To me, [horror is] the Nazis turning murder into numbers so nobody was ever responsible for murder. That's pretty horrible. I live in a city where we spend millions of dollars a day on trains, but we can't feed people. That's horrible. That's scary. That we as human beings can't take care of each other and are really terrible to each other. It's all about these power plays. But as far as what most people consider to be "horror," just seems like an allegory and exploration of tonality. These are archetypal structures we are all interacting with on some level. That doesn't really seem scary to me. Obviously, Freddy and Jason don't exist. They just exist in your mind. They don't make me afraid, which is what I think horror is supposed to do.

What's your working process like in "Outbreak?"

Menton3: [Editor] Denton [Tipton] is really awesome to work with. He can be really hard on you, but he also inspires. So this time they made me do thumbnails that I just really hate doing. But I did them and it was good.

Then I go into the pages. A lot of people ask me for sketch work but I don't sketch. People find that weird but I really don't. I have a YouTube channel where I just show me doing digital work so people will finally believe the fact that I don't actually sketch. So I just dive into the pages and then when I'm done I send them to Denton and if he has any issues he lets me know. But this has been an incredibly fun book to work on. Brandon's writing has been really intriguing and fun to be a part of.

Seifert: My writing process always starts with a hell of a lot of research and a hell of a lot of brainstorming. Both in terms of plot and character elements, but also themes and ideas. With this project especially, of all the projects I've done so far, this is the one I've agonized over the most. It's been the one I've found the hardest. So my working process on it has involved a lot more revisions and going back to the drawing board than I usually do. And then also a lot more going back and figuring out new angles and new things that I need to research.

For instance, one thing I like to do in the stories that I write with science in them is to get the science as close to right as I can, with my layman's understanding of it, with both the constraints of the amount of time I have to do research and the constraints of the story. It's not just techno-babble stuff.

Menton3: Well, the techno-babble stuff adds realism. If the science is right about it, then it's a lot more believable and engrossing of a story. I respect that about you. I think you're really good at it.

Seifert: Thank you! And for me, I really feel that way, too. But I also feel that if you're making up that techno-babble, and you're making up details that aren't based in the real world, then there's a lack of verisimilitude. I feel it's something that people can detect. Whereas if you're basing stuff on reality there's a level of detail and texture there.

Menton3: It's the intentionality of it. The intentionality is you're trying to make something that is real to you in that regard. I think that comes through as storytelling.

Seifert: Me too, definitely... And since ["The Fly: Outbreak"] is about transgenic organisms and humans with animal DNA, and that's something we can actually do now, it's important to get it as close to reality as I can in the story. I had been banging my head against the wall on this project for nine months, and then one day I go, "Oh, one of my best friends genetically modifies organisms for a living." It's what she does. So I bought her coffee and she explained to me how all of this could potentially work. I mean, it couldn't actually work, but she found a bunch of concepts that are actually used in genetic engineering and actually make sense.

That was one of those minor victories for me. To learn something, have it make sense and figure out how to incorporate it in the proper quantity in a story. Enough to add texture but not so much that it distracts you.

"The Fly: Outbreak" #1 from IDW Publishing is available now. Issue #2 debuts on April 22.