On Wednesday, June 1, the relaunch of the DC Comics' superhero universe started its second phase, with the release of the first weekly set of comic books with the word "Rebirth" following the name of the hero featured in the comic.

Four titles came out last week, but the one I'd like to discuss, and arguably the most important one, is "Batman: Rebirth" #1. Crafted by the creative team of writers Scott Snyder and Tom King, artist Mikel Janin, colorist June Chung and letterer Deron Bennett, "Batman: Rebirth" was the opening salvo of sorts for the character, his world, and the immediate future of the Batman franchise.

RELATED: "Batman: Rebirth" #1 Gives Duke Thomas a New Role, Revamps Classic Foe

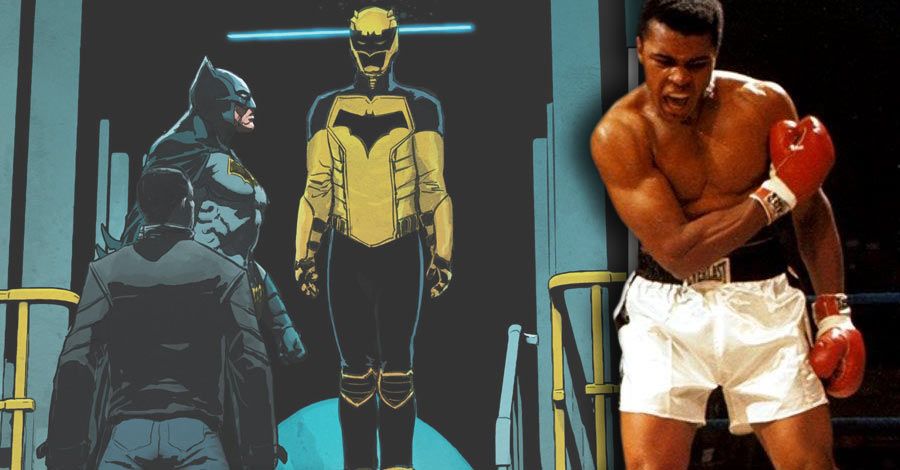

The issue had a storyline involving a supervillain, peril and action, but a significant subplot involved the induction of African-American teenager Duke Thomas into the Bat-ranks. Introduced during the "Batman: Zero Year" storyline sometime back, and later spotlighted in the "We Are Robin" series, Duke Thomas is a young man whose import to the world of The Batman has been growing.

Scott Snyder, arguably Batman's creative mastermind at this point in DC Comics history, has not shied away from social resonance and cultural diversity in his time chronicling the saga of the Dark Knight. Snyder's "Batman: Rebirth" co-writer Tom King is known for rich, complex character narratives seen in books such as Vertigo's "Sheriff of Babylon" and Marvel Comics' "Vision."

Yet, I found "Batman: Rebirth" to be not as engaging as I was hoping for, not the declaration of war on Marvel Comics, as one might expect the first post-"DC Universe: Rebirth" book with the company's (likely) most popular and possibly most lucrative character to be.

After all, a certain film with heavy investment and high expectations did have Batman's name before Superman's, didn't it?

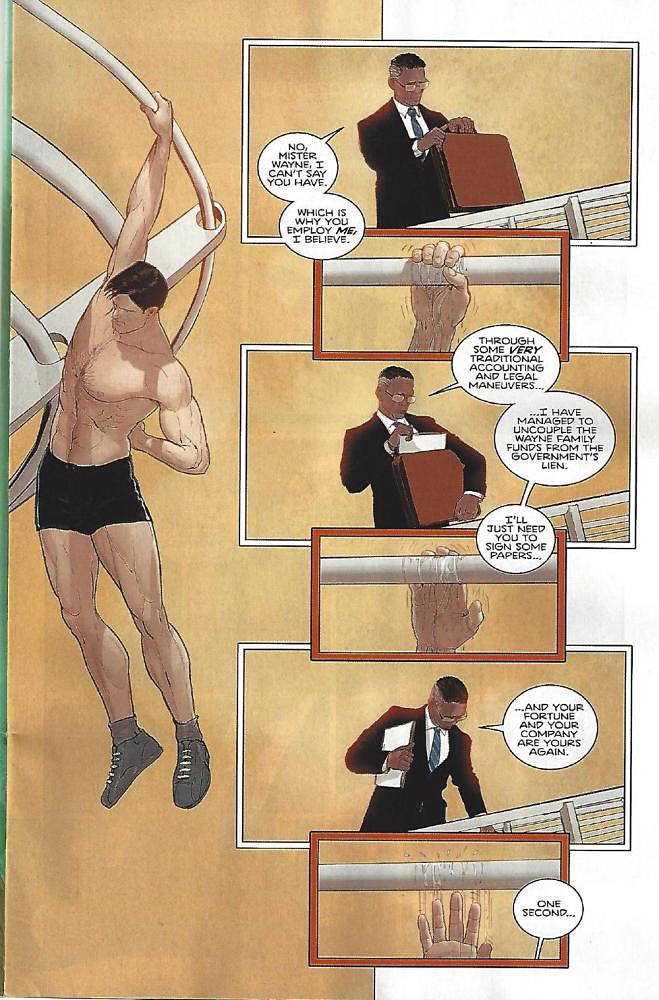

Part of the reason I found the book underwhelming is because the two Black men in the life of Batman/Bruce Wayne came off as appendages, neither of them having any weight of their own or providing any weight to the story. The aforementioned Duke Thomas, and Lucius Fox, the man who really runs Batman's corporation so Bruce can fight crime at a high-level operational scale.

Duke did nothing in the comic book, and Lucius did nothing, either. While I appreciated their story presence, I did not appreciate their lack of potency in said story.

On June 3, two days after the release of "Batman: Rebirth," a real-world tragedy occurred, reported in more media outlets than you can immediately count.

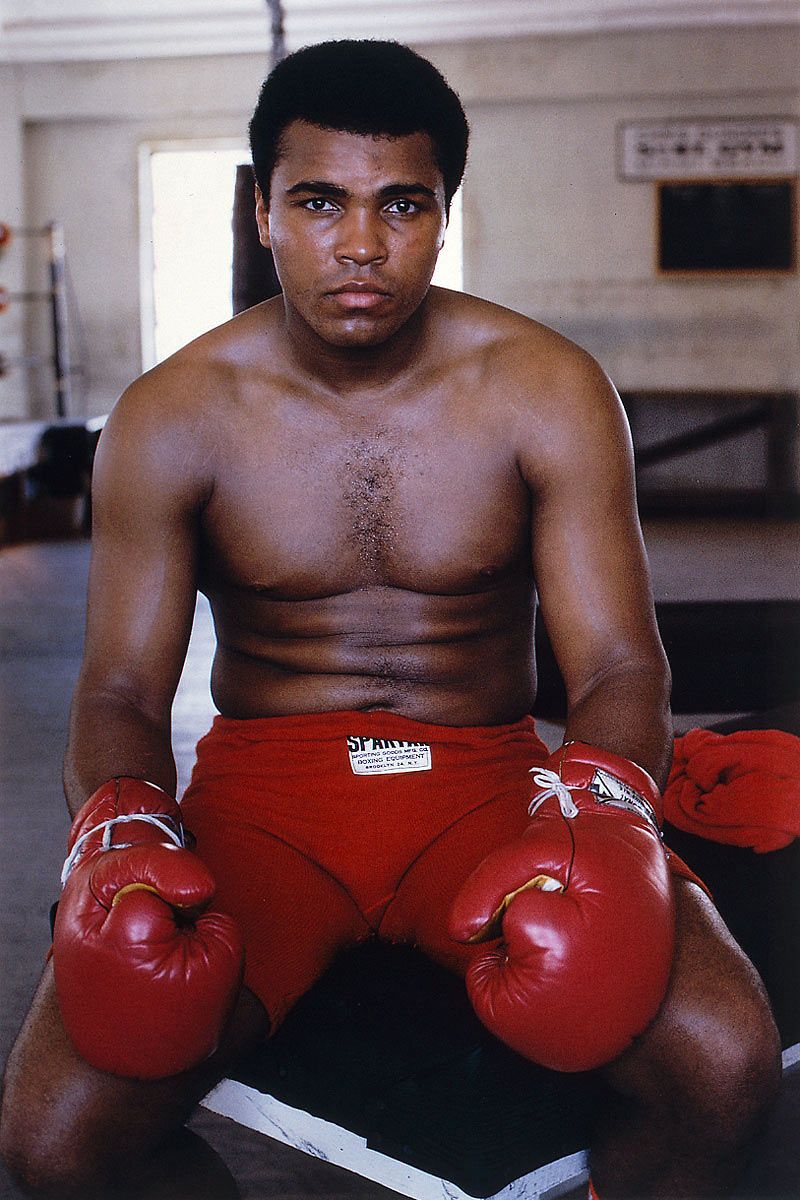

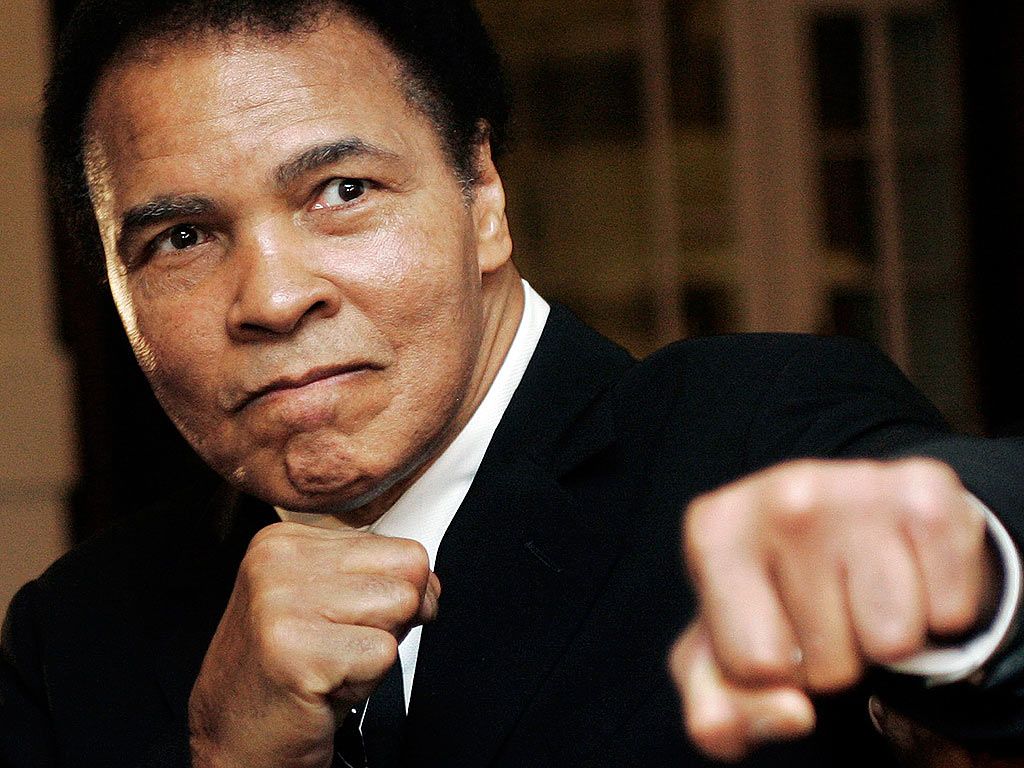

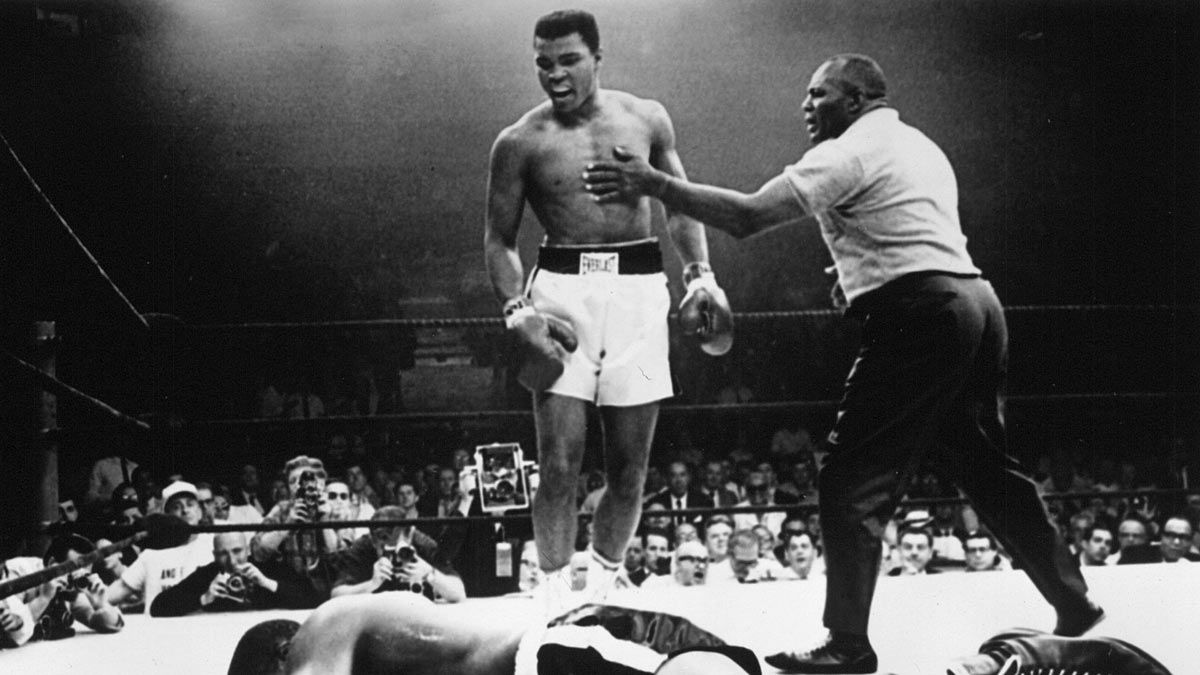

The death of legendary boxer Muhammad Ali.

He died suffering from respiratory complications and Parkinson's Disease, but he lived as an extraordinary man, a supreme fighter, a champion for civil rights, a combatant against the establishment when it came to his anti-war stance and his religious status as a Muslim, and as a father.

The public outpouring in social media, articles, news programs, and various print periodicals, is indicative of Ali's iconic status across generations, his import in American society and his symbolism. While Ali was loved, admired and respected across the racial divide, his symbolism and impact most greatly resides within the Black community.

If Muhammad Ali's maturation and presence, his conviction and compassion, his evolution and accomplishments, represent an always-relevant example of personal and professional success, then we have to examine the representation of Black people in America in our fiction. Our superhero fiction uses the roots of real-life and mixes them with fantastic story elements and constructs, to create the alchemy which gives us the advanced versions of ourselves, the idealized version, the version to which we aspire.

How, then, in 2016, does DC Comics believe a young, urban Black male teenager as sidekick to a wealthy White man of entitlement-supported privilege, represents this aspiration of Black youth? How does it represent a brick on the road to the desired destination of the Black man in society?

American society is now 38 years since the premiere of the sitcom "Diff'rent Strokes," in which two young African-American boys from Harlem were adopted by a wealthy White businessman. Such a dream is no longer in the psyche of Black American youth. Black American boys and girls want to survive, and grow to become Black American men and women.

Muhammad Ali was tested by decades of battle and adversity, but he was forged by an internal will, a fire, a sense of self that was the fulcrum of his existence and the sentiments which have been used for countless memes in the days after his death.

Being the sidekick of Batman is not in step with the present. At a time when DC Comics has initiated the Rebirth of their entire superhero universe, with reverence and excitement, with statement, with promise and promises, their need to be in step with the present while embracing their imaginative legacy has never been clearer.

With that, I submit that the next Batman should be a Black man. It is the idea mentioned in various conversations across years, realized in ersatz Batman-like characters at different publishing houses. The symbolism and potential for exploration possible with a Black man of means taking on the mantle of The Batman would be a controversial cash cow for DC Comics. We could only imagine how much media coverage and attention DC Comics would get from such a move.

Such a man could not be a protege of Batman, as was done with the 2011 series "Batwing," or existing in a parallel world. He would be in this world, in our time, and exist as the means by which DC Comics could show an extraordinary level of courage and confidence, to match the extraordinary conceits of their superhero mythology. It would snuff the categorizations of Marvel's Black Panther and Nighthawk characters as "The Black Batman," rendering such arguments irrelevant in the shadow of a wealthy Black adult male with a bat on his body armor-covered chest. A move like that would be a statement of war against their competitor, Marvel Comics.

And if you're asking what Bruce Wayne would be doing this time, well, at the very least, he would be working feverishly to uncover the cosmic mystery that could lead to the death or salvation of the entire DC Universe. The mystery first indicated in "DC Universe: Rebirth," the one that lies at the core of Chief Creative Officer Geoff Johns two-year macro-epic of great proportions.

The superhero genre is uniquely qualified to take chances, in order to present the kinds of stories which are both imaginatively magnificent and powerful in their social relevance. Both Muhammad Ali and Prince, incomparable Black men and icons of the past and present century, were certainly still alive when the DC Comics' Rebirth plans were being formed and refined. The stories of our times need not predict when our real-life heroes will expire and pass away. They should, however, be a reflection of our times, issues, concerns, struggles, and victories.

Where the mythology of The Batman is headed will be revealed more over this month and months to come in the "Rebirth" titles, but right now, it still reflects a worldview that is out of touch. More corporate and creative valor is required.

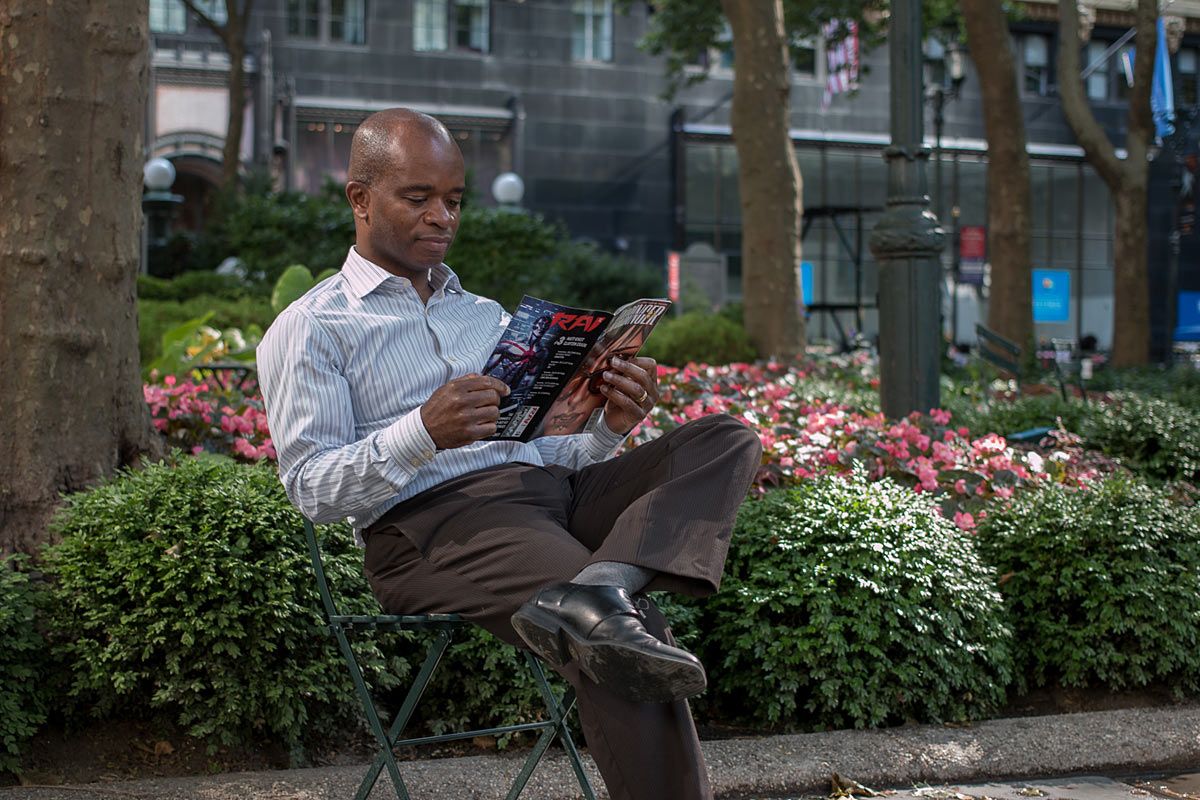

Joseph Phillip Illidge is a public speaker on the subjects of race, comics and the corporate politics of diversity. In addition to his coverage by The New York Times, CNN Money, the BBC and Publishers Weekly, Joseph has been a speaker at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, Digital Book World's forum, Digitize Your Career: Marketing and Editing 2.0, Skidmore College, The School of Visual Arts, Purdue University, on the panel "Diversity in Comics: Race, Ethnicity, Gender and Sexual Orientation in American Comic Books" and at the Soho Gallery for Digital Art in New York City.

Joseph is the Head Writer for Verge Entertainment. Verge has developed an extensive library of intellectual properties for live-action and animated television and film, video games, graphic novels and web-based entertainment.

His graphic novel project, "The Ren," about the romance between a young musician from the South and a Harlem-born dancer in 1925, set against the backdrop of a crime war, will be published by First Second Books, a division of Macmillan.

Joseph's newest comic book project is the upcoming Scout Comics miniseries "Solarman," a revamp of a teenage superhero originally written by Stan Lee.