There are a lot of existential questions one could ask about this project: Why does it exist? Why is it an original graphic novel instead of a comic book series? Why is it subtitled “Earth One”? What does that mean, this year? What does it have to do with Superman: Earth One? Who on Earth is it for? Why was DC Comics promoting it as the more-or-less official Dark Knight Rises tie-in, distributing previews the week of the film's release? And so on.

The whys I asked myself the most once I actually started reading it, however, regarded the particular choices writer Geoff Johns made while creating it. It's full of significant, even radical, changes to the familiar elements of what you might think of as the basic Batman story and cast, and many of those changes seem completely random, in service of nothing in particular ... save maybe a pretty messed-up message.

I’ve read just about every single comic Johns has written, and while I wouldn’t’ go so far as to say I’m a fan of his writing, I’m definitely very interested in it. I enjoy reading it for its faults as much as for its strengths, and I share his interest in the colorful characters and deep, complex history of the DC Universe, which the bulk of his writing has been concerned with.

In my experience, his very worst work has been that done without the crutch of DCU continuity, the sort of anything-goes wheel-reinventing he’s attempted on the recent Justice League reboot, with which he was paired with the direct market’s most popular artist Jim Lee, who brings strong drafting skills to Johns’ script, but little personality, flair or emotion. Johns' very best work, on the other hand, has involved in-progress characters he was shepherding from a pre-established Point A to his own desired Point B, with artists capable of emotive character design and accessible, warm work. (His too-brief run on Superboy with Francis Manapul leaps immediately to mind, as does his early Stars and STRIPE with Lee Moder and his long, uneven run on Green Lantern with various artists of various skills and styles.)

With Earth One, Johns is reinventing without the benefit of the continuity wires or the DCU net, and he’s reinventing probably the most malleable, flexible character in comics, even if it’s unclear what the mandate here is exactly. (Like, if Superman: Earth One was Superman for the Twilight/YA book audience, what’s the point of this one? There are already plenty of Batman graphic novels that meet that particular need, and "A Dark Knight For A New Generation" on the back cover sounds a little grandiose, coming as it does when there's a Batman movie in the theaters and one Batman cartoon series for kids just wrapped up and another's about to launch.)

What he’s come up with is basically another Batman comic, one that is original and parallel to those starring the “real” Batman (like the All-Star Batman series was, but less faithful to the source material, or like a rebooted, "New 52" version of Batman, if DC had actually gone ahead and rebooted Batman like they did the rest of the universe). This is an Elseworlds Batman, lacking only the "Elseworlds" logo and the sort of strong What If … Batman Was Peter Pan? or What If … Bruce Wayne’s Parents Were Killed by Bigfoot? sort of hook. Basically, for want of a better comparison, this is Geoff Johns and Gary Frank on Ultimate Batman.

The most obvious point of comparison within DC’s library of Batman books is Frank Miller and David Mazzucchelli’s Batman: Year One, which this is a sort of riff on (and say, there’s a fine example of a Batman book filling the Batman-for-YA-book-audience market right here!), with the fourth panel serving as Frank’s visual allusion/homage to a famous image of Mazzucchelli’s of the shadowed Batman running across Gotham rooftops.

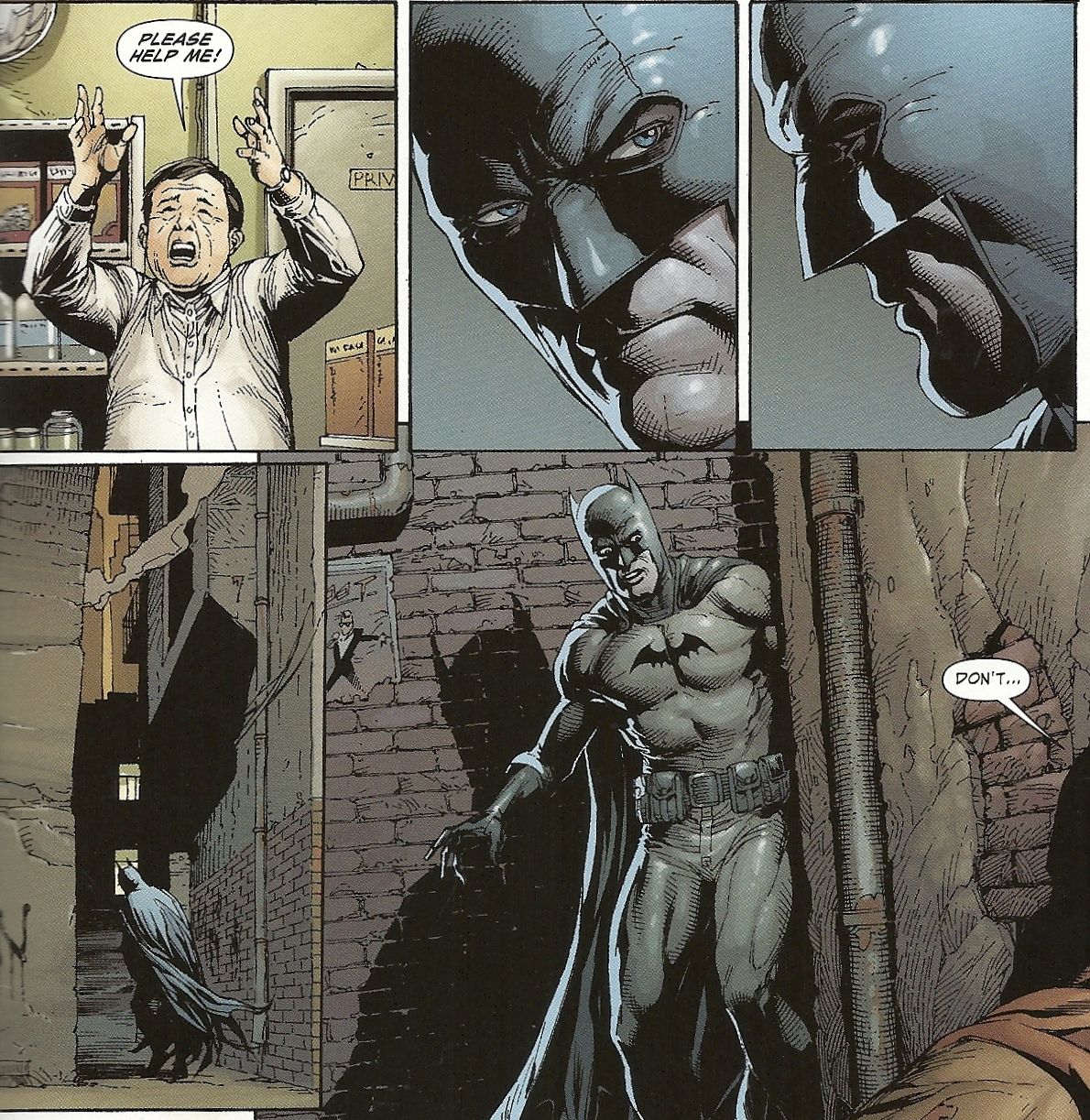

The single scene from Year One that most heavily informs Earth One, however, is that one in which the brand-new Batman messes up while trying to stop a few guys from lifting a television set from an apartment, and almost dies on a fire escape. Johns and Frank are interested in exploring that Batman; the new, struggling wannabe vigilante of his first nights out, not the polished, professional crime-fighter we’re used to.

That’s not a bad route to go, of course, but the choices Johns makes while in the process of doing so are, as I say, pretty random.

Not only is this Batman not omnipotent, he’s barely competent — this Batman didn’t travel the world, using his wealth, time and focus training with master detectives and martial artists in order to become a perfect crimefighter. He was simply trained to fight by Alfred Pennyworth. He’s not a very good fighter, however, nor is he much of a detective. In fact, he lucks his way through this particular conflict, and it’s up to others to save his life and avenge the deaths of his parents.

This Alfred isn’t a butler, but a former Royal Marine hired by mayoral candidate Thomas Wayne as a security consultant, his first night on the job being the one on which the Waynes are killed, and he’s given sole custody of young Bruce. It’s a strange, reflexive and defensive take on the character, akin to Johns’ take on Aquaman, in which he tries to ratchet up the macho of the character to such an extent that it strains against the mold.

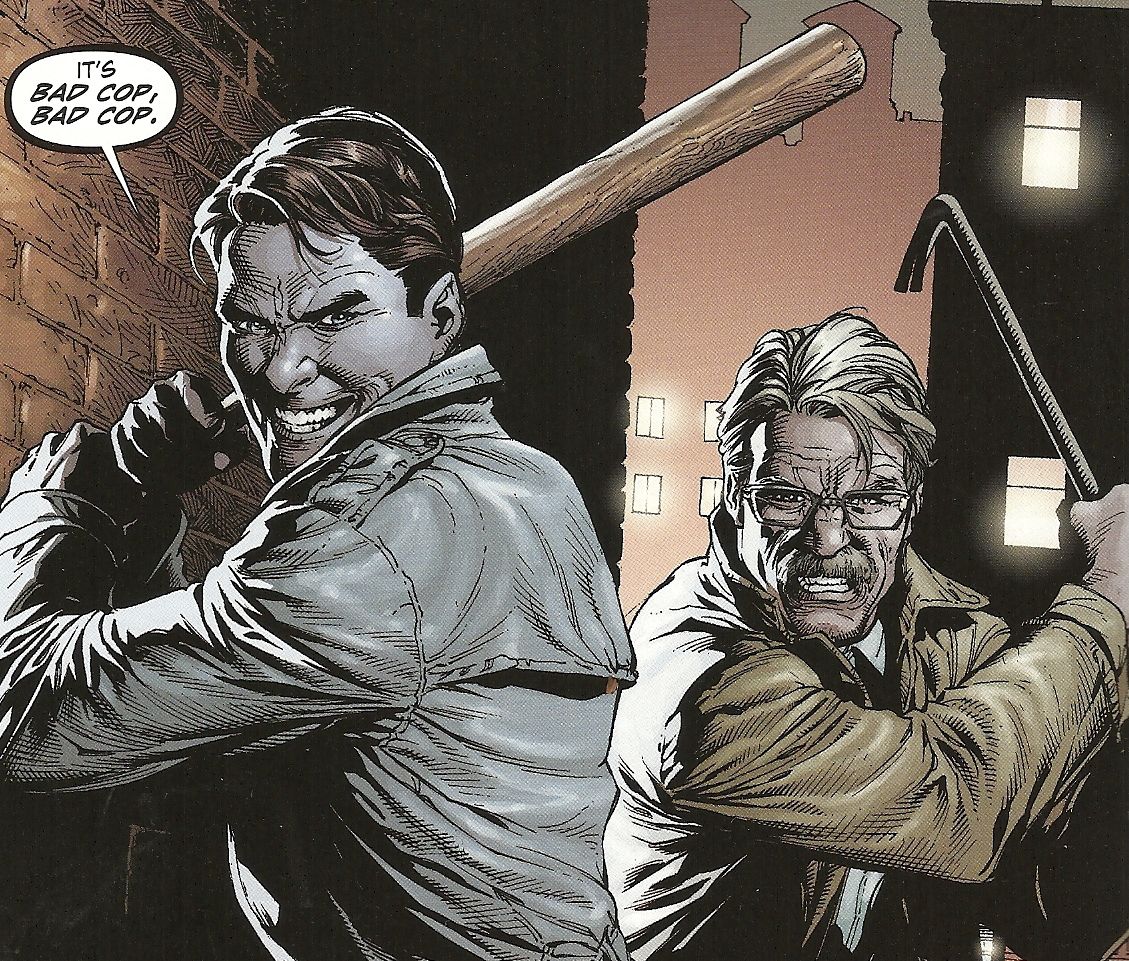

James Gordon is a broken-down, cowardly and corrupt police officer, crawling like a worm to protect his teenage daughter Barbara from reprisals. Unlike Batman, he actually has something of a character arc in this book, and, by its end, he’s finally on the path to being the heroic cop we expect him to be. Unfortunately, he begins to show a backbone not by enforcing the law, but by picking up a crowbar and joining his partner in beating information out of a bad guy.

Harvey Bullock is slim, fit and handsome (that's him on the left), an attention-hungry but genuinely idealistic television star who comes to Gotham City to solve it’s most famous cold case and pump up his TV Q-rating in the process. He too changes by book’s end, and will likely evolve towards the more slovenly Bullock that has been the standard model.

And The Penguin isn’t really “The Penguin,” but Mayor Oswald Cobblepot. (First the plot of a 1992 feature film, now this; they sure have gotten a lot of mileage out of a plotline from two episodes of the silly 1966 TV series where The Penguin ran for mayor, haven't they?)

The mode isn’t necessarily more realistic, other than Batman being more Phoenix Jones than Zorro. Sure, Johns and Frank took a lot of the super out the superhero whose name is in the title, but theirs is still a comic book in which the mayor of a major American city keeps a serial killer on his payroll, and pays him not with money, but with little girls.

The great weakness in the book, however, is how it essentially proves Batman’s beliefs and philosophy about crime-fighting and doing what’s right wrong. Rather than being right, this Batman is quite clearly shown to be wrong, and naive and even a bit silly on top of it. He’s not a hero in the traditional sense of the word; he’s simply a protagonist.

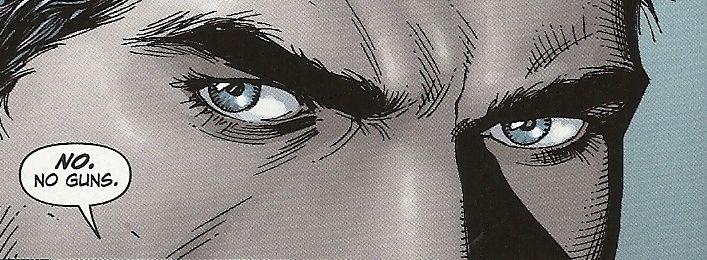

Throughout the book, Batman refuses to use a gun to wage his vigilante war on crime, a point former soldier Alfred continually argues with him. He also refuses to take a life, leaving the serial killer -- the one with a basement full dead little girls -- in handcuffs for the police to take in.

When Batman finally confronts Cobblepot, the man who orchestrated his parents’ murder, Cobblepot stabs him in the gut with a blade-tipped umbrella, clobbers with a paper weight, unmasks him, stabs him again, and is about to slit his throat when Aflred blows him away with a shotgun.

Were it not for a big gun and a willingness to kill one’s foes, Batman would be some combination of dead and unmasked. I guess that’s one thing that differentiates this Batman comic from all the others: It’s the one that calls bullshit on Batman’s opposition to firearms and lethal force.

With so many creative choices and mythos changes made, statistically speaking, there had to be good ones.

I liked Frank’s Batman-with-eyeballs version of the mask, as it’s something we so rarely see (outside of Alex Ross paintings and the movies). It fits the more human version of the character, as he has a soul we can peer into, rather than two white, angry pupil-less triangles, and it allows us to read fear, surprise and angry in his first adventures as a man in a bat-costume.

That bat-costume is a rather fine one, too. Overall, I don’t much care for the design, but compared to other, more recent “realistic” takes on the Batman costume, like the armored version we saw in the Christopher Nolan Batman movies and the recent Arkham video games, or the overly busy New 52 ensemble, this one manages to look functional while also resembling something a comic-book superhero might be able to wear while also running, jumping and punching.

I also liked the revelation of Martha Wayne’s maiden name, which, since I’m spoiling things anyway, is Arkham, descended from those Arkhams. That change really does put Bruce Wayne/Batman front and center in this universe, as suddenly all those criminally insane people he will eventually fight are likely tied to him personally and, as hinted at here, Wayne is engaged in a lifelong struggle to come to grips with the fact that insanity may run in his family. Basically, it literalizes the decades-old Is Batman a little, uh, batty? conflict that’s run through so many of the comics (and cartoon and film adaptations).

Although we won’t be seeing Cobblepot again, other villains are hinted at throughout the book, including a cliffhanger appearance by The Riddler, a brief appearance by a boy named Harvey Dent, the name “Crane” gets name-dropped and we see a collection of clown dolls in a room at the abandoned Arkham Asylum. Barbara Gordon is seen sketching a Batgirl costume, and her dad and Bullock have both changed their ways and started on new paths by book’s end. It will presumably continue in other volumes, as Superman: Earth One is to continue, and it’s possible that a lot of what is ugly in this book will eventually recede, and maybe even it’s tacit endorsement of torture, guns and killing will be emphatically denounced in coming volumes.

That would be nice, but I’m not in a hurry to read those volumes.

Ultimately, Earth One is maybe the most confounding, confusing Batman comic I’ve ever read (and, like comics written by Geoff Johns, I’ve read a lot of Batman comics). It reads easily enough, of course — together or apart, Johns and Frank are both accomplished, experienced professionals — but it’s just one strange choice piled atop another, and lacks either clearly expressed point of view to justify those choice or a great and unique artistic vision of the sort that helps the weirdest and wildest of the various alternate Batman stories get over.