"God gave us memory so that we might have roses in December." -- J.M. Barrie

In 1987, Tom Batiuk, the cartoonist behind the nationally syndicated "Funky Winkerbean" comic strip, teamed with artist Chuck Ayers to launch a spinoff strip: "Crankshaft." Later, when Batiuk began to chafe against the limits of gag-a-day storytelling, both strips evolved into real-time sagas of America, laced with comedy and tragedy in equal measure.

While "Funky" followed a younger generation as they reached adulthood and all that it entails, "Crankshaft" chronicled the exploits of an older generation dealing with the turmoil that plagues us in our twilight years.

Two long-running narratives in the "Crankshaft" strip followed the lives of two residents afflicted with Alzheimer's dementia -- one of them, Lucy, was followed from early symptoms to the disease's final stages, all unfolding in real time across the strip for over a decade. The other narrative dealt with the character Ralph, as he recalled a lifetime of memories with his wife Helen - memories that she no longer shared with him.

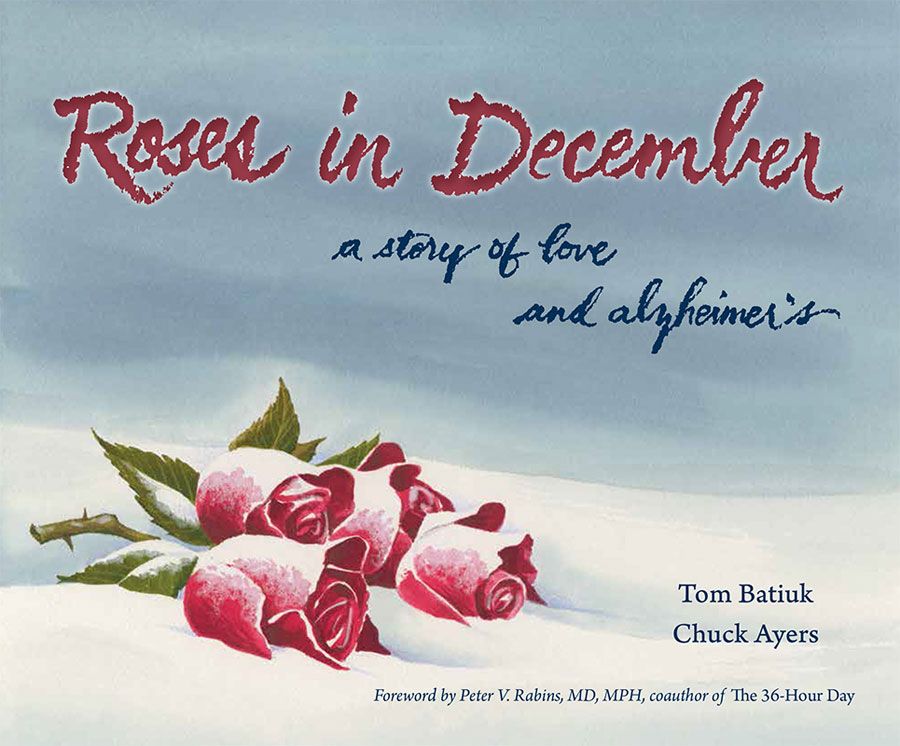

"Roses in December: A Story of Love & Alzheimer's" collects all the "Crankshaft" strips that unfold the stories of Lucy and Helen (and their family and friends who cope with the loss -- yet continued presence -- of their loved one) into one handsome volume.

CBR News spoke with Tom Batiuk about the importance of telling stories that resonate with his readership, and why comic strips -- even in this age -- remain a vital and irreplaceable storytelling form.

CBR News: What inspired you to tell a long-running story about Alzheimer's dementia?

Tom Batiuk: Part of it was the appropriateness within the context of "Crankshaft," where I'm dealing with an older community. Crankshaft is an older guy and the two neighbor ladies, Lillian and Lucy, were older. It was just an opportunity to explore it within that context. That's naturally where it's going to occur, and rather than ignore things that can happen as people get older, I think it's nice to integrate them and see if you can enrich the characters by telling stories with a little more substance to them.

When I decided to do that, I obviously went and started doing a lot of in-depth research. Then, inadvertently, something cropped up as the story was moving along, which kind of proves my first point. Chuck Ayers, who works with me on "Crankshaft" -- he does the artwork, I do the writing, and Chuck's artwork is absolutely amazing -- his dad was diagnosed with Alzheimer's, so we started dealing with that in the middle of the storyline.

That's what you want to try to do -- you want to touch on topics that resonate with your readers and that touch some part of their lives. You're always trying to do that and that's why you tackle things like this.

One of the most interesting aspects of the storyline is how you explore the experience of both the people afflicted with the condition as well as of their caretakers and loved ones. Was it important to you to explore the full impact of the condition?

Sure. First of all, like you say, it's not just the person who has the dementia, but the people who are helping to take care of that person -- they're a big part of the story, too. The way the population is aging, the baby boomers, you're going to be seeing more and more of this. This is where you pull things in -- a lot of the caretaker stuff came from experiences with my parents when they got quite old. They weren't suffering dementia, but they needed caregivers. They needed help, and all that stuff can be applied in some way or another to the work.

A daily strip is sort of the perfect venue for this sort of real-time unfolding drama.

Yeah, it is. The American comic strip is an incredible unique art form, because there's no other form where you've been in people's houses every day. For the longest time, it's just held this very unique spot where people get newspapers and these people end up on their tables, in their houses. They share experiences with these characters in, I think, a deeper way than you do with a novel or a movie. Once the book is over, it's gone, but these strip characters are still there. That's one of the reasons I like to have my characters aging and continuing to grow. They're kind of growing along with the readers.

When you put these strips together as a book, did you worry about the story losing any of that sense of time unfolding without the in-between strips and decade-plus of time passing?

You certainly have to watch out for that. You've got to go through and keep it focused, but you don't want to have a strip where we're celebrating Christmas and all of the sudden, it's Fall again, two pages later. You've got to kind of try to balance that, and it's difficult because a daily strip is not being written as a graphic novel, per se. Quite honestly, I'm amazed the work hangs together as well as it does, because it tends to create a narrative that is not seamless. I think we've taken out enough of those bumps to make it not too jarring. It seems like it's moving forward in a natural progression.

Over how long a period of time was the serialization of the strips in "Roses in December"?

They were started in the mid-'90s, and it initially started with Ralph. It was one of those things -- you could rarely do this, but I can actually pinpoint what started me thinking about Alzheimer's dementia. It was that phrase of James Barrie's, "God gave us memory so we could have roses in December." I just took that and I thought, Okay, then the Alzheimer's and dementia steal away that nice gift. So I started to explore that.

When I jumped in, Ralph had his wife in the nursing home, so I could explain it in those terms -- that's why she was there. It was already set. Then, I started the research and started dealing with all that stuff and found that I wanted to go back and explore it from its beginnings -- which is why I then involved Lucy, the next-door neighbor.

You can see that in the book. It starts off with Ralph visiting his wife and some tragic humor, but then it goes much more in depth when it shifts to Lucy and Lillian's story. Of course, then you come back to Ralph and his wife and fill in their back story and add so much depth there as well.

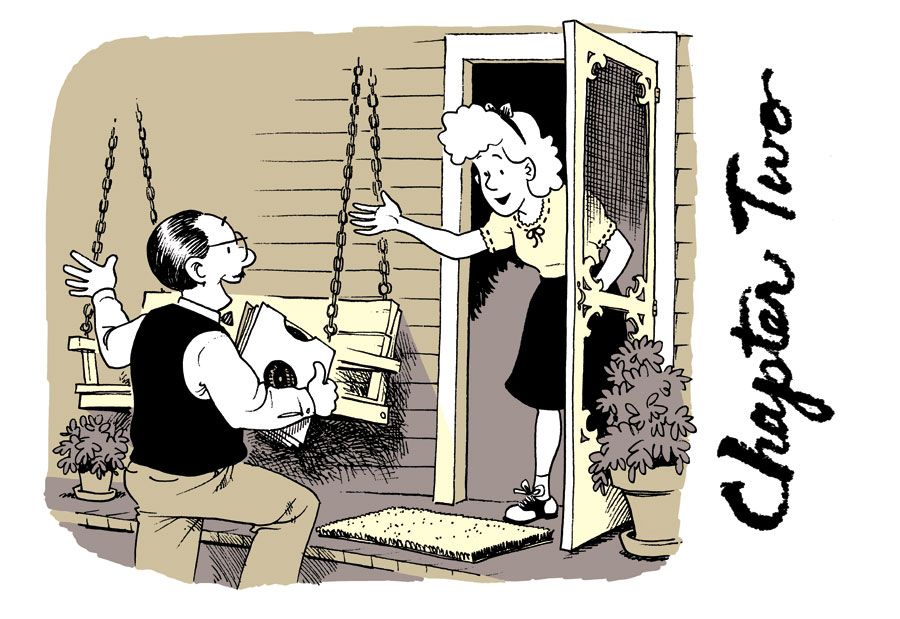

Yeah, and I wanted that back story in there. That's fascinating to me, because you forget what people's lives were like. When you encounter old people, that's where they are. You kind of forget that they were young and they had dreams and plans. I wanted to go back and look at Ralph and Helen's going to New York City to try to have a larger life and live out some dreams. I wanted to put all that in context.

One of my favorite storytelling tools you employed was framing the flashbacks as snapshots in a photobook. How did that technique come to you?

I think I started it first in "Funky." When I did it in "Funky," I actually used those little corner tabs. People probably don't even know what those are anymore -- you'd get a photo book and put these things on the corners and stick them in. With "Crankshaft," we went a little bit more sophisticated and tried to do it with color, sort of like sepia tone photographs and things like that. We used that as a way of capturing that. I thought that worked fairly successfully. Again, a lot of it is due to Chuck Ayers. His ability to pull that off is like black magic to me. He's really good.

Book collections of comic strips are certainly nothing new. The "Prince Valiant" reprints can't come out fast enough for me right now.

I know. I go into my comic shop and say, "Do you have any old cartoons?" Those Alex Raymond "Flash Gordon" books that came out were astonishing.

Oh, yeah, they're gorgeous. So strip reprints are common enough, but was there a particular point when you realized this long-running arc could be pulled out of the greater strip to act as a stand-alone book?

Sure. What made me think along those lines, in my other strip, "Funky Winkerbean," I had a story about a character named Lisa who died of breast cancer. I'd gone to the Kent State University Press to see if they'd want to collect that material into one complete volume. They did, and it worked really well. It was highly successful, but for me as an artist, it was especially nice to have that work collected in a book like that.

It was a pretty natural thought process to go back with this Alzheimer's material and say, hey, would you like to try to spool the same line one more time and collect all of these strips into one book? Fortunately, they said yes, and I think they created a beautiful book.

When assembling the book, was it difficult to choose strips for inclusion and keep the focus specific to the storyline? I imagine that a few strips touched on the storyline, but a little too tangentially, and wound up on the cutting room floor.

In a sense, it was. The primary focus is that the book has to flow as well as it can. You're right that there are moments when things had to be left out. My solution was to actually pull more things in. There's one story in there, for instance, about the violin the sisters have, and it had actually been a crossover with "Funky Winkerbean." In order for that story to make sense, I pulled in the "Funky" strips, too. It all makes sense and everything fits. The same thing happened when they steal the Tiffany lamp -- not steal it, but Funky finds the Tiffany lamp that Lucy had inadvertently thrown out in the trash. Again, I need to pull in that extra material, so it's not as painful when you get to add more stuff to it!

The Alzheimer's stuff was pretty extensive, so there are very few one-offs where I couldn't include something because it's just one strip. It was tricky. You just have to make sure you're paying attention to what you're doing. Then read it and make sure that it flows.

You're still plugging away with "Funky" and "Crankshaft," correct?

Yes. My time is totally occupied with those strips. That's a total focus. There are the books like this one that just came out. And "Funky" -- the KSU Press is collecting the complete "Funky Winkerbean," so there's a volume of that stuff every year to work on, which is a lot of fun. I love writing the intros and putting everything in context. It's fun. Working on the strips and working on the books are my main concerns right now. We just put volume five to bed -- volume five of the complete "Funky Winkerbean" will be coming out in the Spring, and Maggie Thompson wrote a wonderful forward for it.