Nancy Goldstein’s Jackie Ormes: The First African American Woman Cartoonist suffers a bit from a lack of access to information.

While the author’s sources include Ormes’ sister and a cartoonist colleague, and her subject was, as she put it, “a saver,” she also notes early on that she didn’t have letters to or from Ormes, a traditional source for what’s going on in a biography subject’s head, nor, apparently, did she have any sort of journal or diary.

The resultant book then is, perhaps, imperfect. Goldstein makes quite clear what an incredible, colorful person Ormes was, and what a fascinating life she lead, but the biographical sections are tantalizing: One may find oneself wanting much more detail, to join Ormes in the newspaper offices or society functions she covered and put on.

And while there is an awful lot of comics art reproduced within its pages, but due to the special and financial limitations of this book (it’s not an archival project, after all) and the simple lack of availability of original art, original newspapers her work was published in, or even copies or microfilm of those papers, much (too much) of Ormes’ work is lost to history.

No matter. Perhaps someone will find more and more immediate sources in the future, and turn out a big, fat biography that reads like a novel. Perhaps a comics publisher will devote their resources to a complete—or near complete—run of one or more of Ormes’ comics.

In the mean time, Goldestein’s book is a wonderful introduction to a woman who turns out to be as fascinating a person as you could hope to read about, an incredible artist and cartoonist who was pioneering not just for the reason given in the sub-title, but because of how far ahead of her time much of her work was. Ormes’ life and work seems even more exciting, because so much of what Goldstein does seems like an act of discovery or introduction: Here’s one of those great real-life cartoonist characters who, chances are, you’ve either never heard of, or never heard so much of.

Ormes spent her career in newspapers, drawing cartoons off and on from 1937-1956, but she was also proofread, covered society and sports and, on a few occasions, was a crusading, Lois Lane-like girl reporter (She referred to the male reporters as “boy reporters"). While she was born in Pennsylvania and spent some time in Ohio with her husband’s family, she spent most of her life in Chicago, where she was heavily involved with the art scene, the fashion and social scenes and was politically active enough to get her own hefty FBI file (which Goldstein spends a brief chapter on).

She had four major comics features, each of which Goldstein devotes attention to in the book, to varying degrees.

The first was Torchy Brown in "Dixie to Harlem", a year-long strip following a farm girl from the rural South to New York City, where she wants to make it as an entertainer. Only 12 strips are reproduced here.

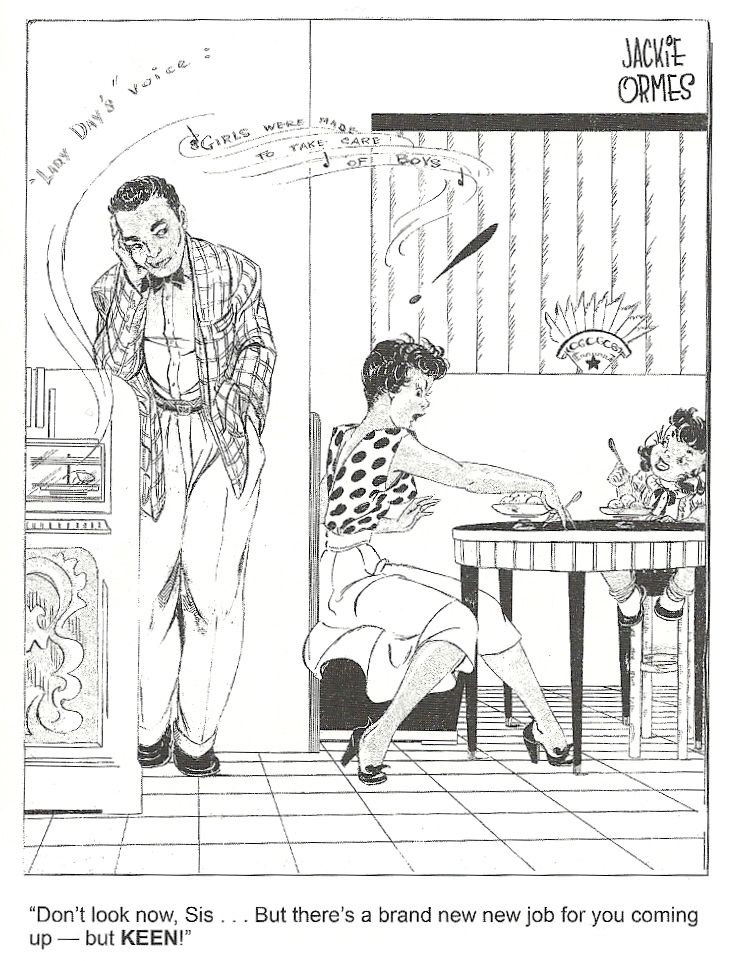

That was followed by Candy, a short-lived one-panel cartoon featuring a sexy, sassy maid making sly observations about her employers and society in general.

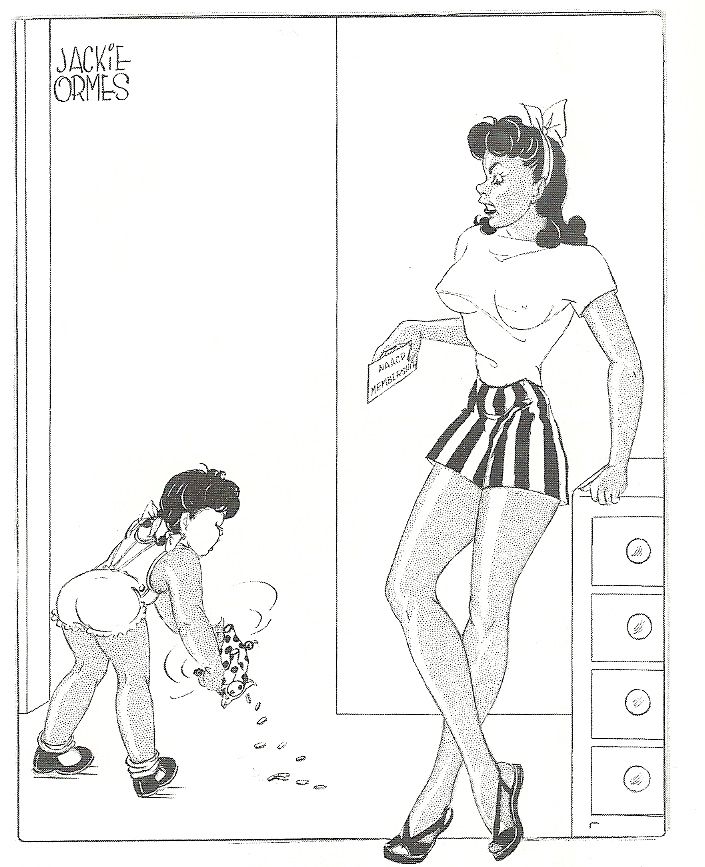

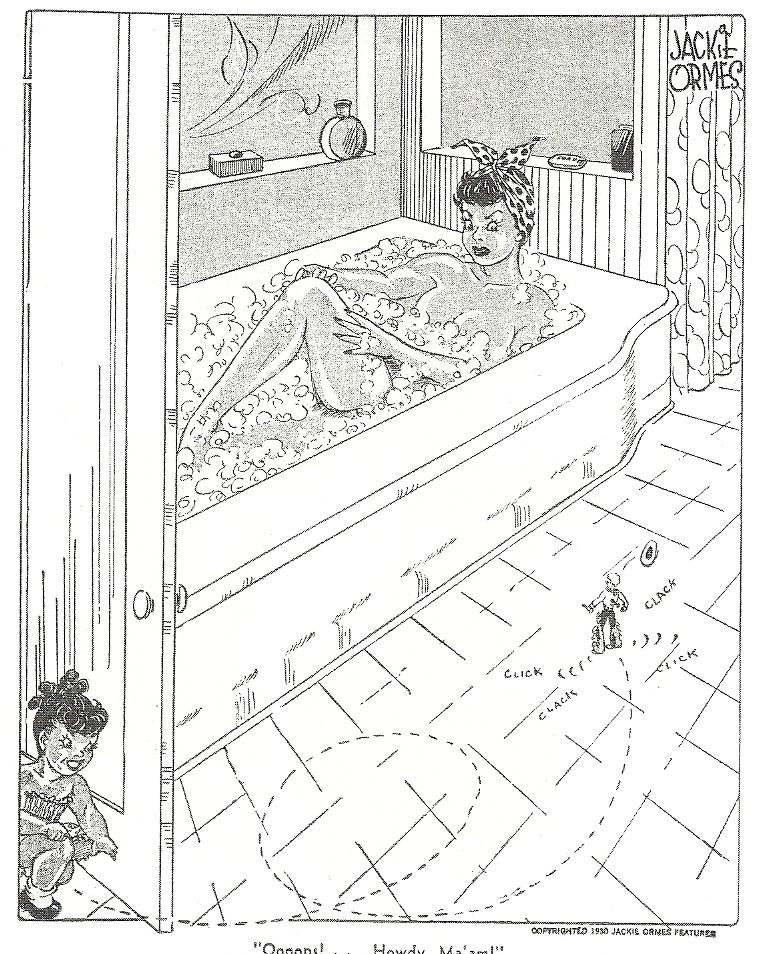

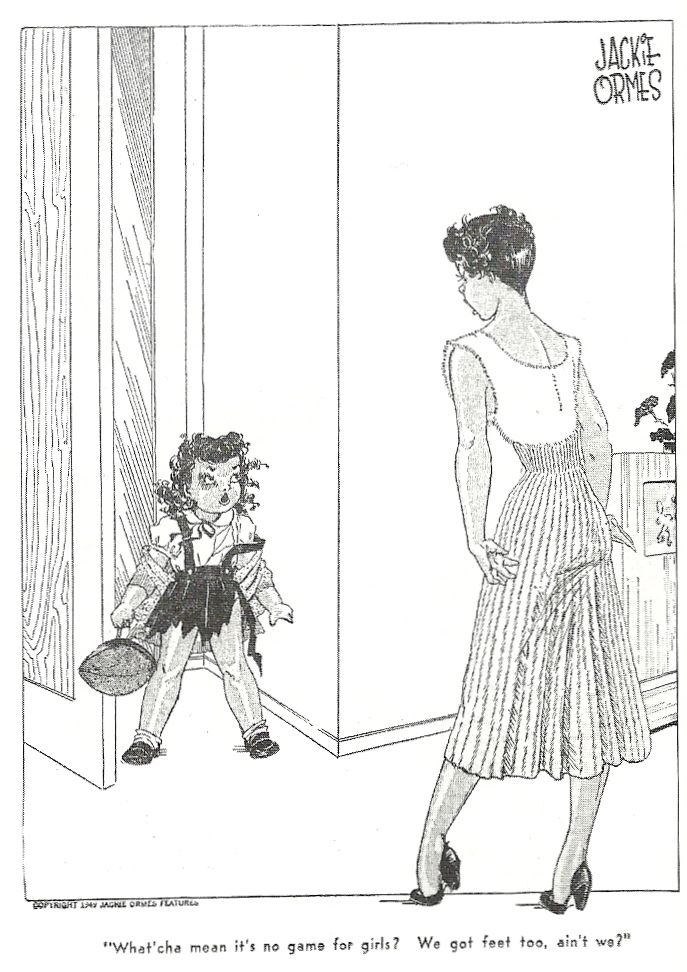

Next was Ormes’ most successful feature, Patty-Jo ‘n’ Ginger, another one-panel cartoon. It starred doll-like little girl Patty-Jo (Ormes would go on to license that character as an actual doll, and she became the first black doll) saying the darndest things, while her older sister Ginger, a beautiful girl with a pin-up figure and an infinitely deep and varied wardrobe, reacted silently.

And finally there was Torchy in Hearbeats, a full-color soap opera/adventure strip, differentiated from others of the era by the all-black cast and Ormes’ sexy, often-daring portrayal of her lead. That, and the “Torchy Togs” paper dolls Ormes often included, featuring a scantily clad drawing of Torchy and various outfits Ormes designed to dress her in.

That last one features some of the best and most accomplished art, and the most sophisticated storytelling, and is best remembered by comics historians for its forward-looking attitude towards social and racial justice, but Goldstein makes a compelling argument that Patty-Jo ‘n’ Ginger is Ormes best work.

The book contains over 80 installments, featuring commentary to help explain some of the gags and references—it ran weekly from 1945 to 1956, and often commented on the big news of the week—and the dialogue caption reprinted in the book’s font to make it easier to read.

This cartoon does seem to distill various aspects of Ormes’ life and work into a single feature. There’s the beautiful woman with all the great clothes—whom Ormes modeled after herself as with her other leads—the little girl that inspired the doll with her own vast wardrobe of cute outfits, and constant commentary on issues important to Ormes.

As Goldstein explains, the reason Ormes was able to get away with so much in her strips wasn’t merely that comics strips could always say things that editorials couldn’t or that she had a seemingly naïve little girl saying them, but because Ormes worked for the weekly black newspapers of her day, she was free of the various layers of self-censorship that would have plagued her contemporaries at the major, mainstream “white” newspapers and syndicates.

Cartoons like these—

—from respectively, seem daring by 2012 funny page standards, after all.

That disconnect between the subject matter and the time it was produced is ever present while reading Ormes’ work reproduced here. Black characters in comics of any kind before the 1960s are so tended to be portrayed in such cringe-inducing ways that it can be difficult to encounter them today in books collecting the work of past American masters.

But here are smart and beautiful black women, adorable, darling black children, upwardly mobile, politically aware black families, and ambitious, attractive black professionals, appearing in comics drawn at the same time, or, in some cases, years before, Mandrake the Magician’s Lothar, The Spirit’s Ebony White, Young Allies' Whietwash Jones and the unfortunate caricatures of some Disney comics.

That is important, and it’s important to consider when we look at troubling racial stereotypes from the Golden Age and excuse it all simply with a “those were different times” or “no one knew any better,” because obviously Jackie Ormes and her editors and peers and thousands of readers did know better.

But it’s also important not to think of Ormes simply as a pioneer in her field, as one of the first women, as one of the first African-Americans and the first African-American cartoonist to succeed in the field of American newspaper comics. Or as someone who got race right years or, in some cases, decades before the rest of the funnies pages and comic book field caught up.

She was also a hell of an artist, and Goldstein’s book gives scores of examples of her work. Ormes drew beautiful women, cute kids, handsome men, elaborate and well-appointed backgrounds and amazing fashions.

She had a fine, delicate line, and was downright masterful in her “acting,” as so many of Ginger’s reaction faces betraying various emotions evidence. And she knew how to marry a single image to a single line of dialogue in order to deliver a direct-hit of visual/verbal information, the very essence of comics-making.

In other words, while Jackie Ormes may be the first African American woman cartoonist, she was also a cartoonist, and damn fine one at that.

Goldstein’s book doesn't suffer a bit form a lack of sources on that front. Sure, it would be great to read whole story arcs of the two Torchy comics, but there's more than enough of Patty-Jo 'n' Ginger in here to prove Ormes was someone worth reclaiming, remembering and celebrating—for the work she produced at the drawing table as much as anything else.

********************

Jackie Ormes: The First African American Woman Cartoonist by Nancy Goldstein, The University of Michigan Press, 225 pages, $35