"Yes, and her tears flowed like wine

She's a real sad tomato, she's a busted Valentine

Knows her mama done told her, that the man was darn unkind"

When it came down to writing You Have Killed Me, style came before plot. Joëlle Jones and I knew we wanted to do a comic book that paid tribute to the private detective lore that we loved, but we had to decide how. No irony, no modern context, no gimmicks--we wanted to do it straight. But how straight was too straight? Where does homage become rip-off?

Before I sat down to type a word, I had what could be called "the Hollywood pitch." It's that thing they do in the picture business, where everything is broken down into two comparable things and, by their combination, we can believe the new thing will be twice as successful as the old. I want to make Movie C, and it's Movie A meets Movie B.

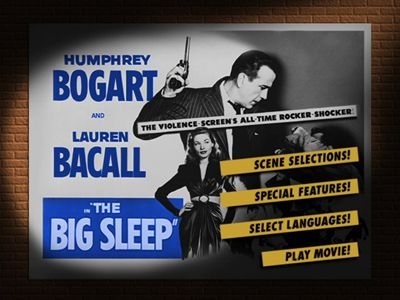

You Have Killed Me is Michelangelo Antonioni directing The Big Sleep.

That's how the pitch began, and it's the descriptive that has stuck with the book since. I've said it often, and it still holds true.

If The Big Sleep isn't the quintessential private detective movie, it's at least the quintessential Bogart and Bacall movie. Directed by Howard Hawks, based on a novel by Raymond Chandler and adapted by three writers, including William Faulkner and Leigh Brackett (the writer of Rio Bravo and later, the most non-quintessential Philip Marlowe picture, Robert Altman's The Long Goodbye), it was released in 1946. Though it has shades of film noir, it's not a snug fit in terms of that artistic movement. Not as dark, not as cynical, it's rooted more firmly in the pulpy traditions that spawned it. Humphrey Bogart stars as Marlowe, a PI that Chandler described as "a white knight in a trenchcoat," and indeed, he would come to embody the idea of the shamus as a sort of modern-day noble warrior whose armor has seen better days. Marlowe's outer shell can use a bit of a polish, but he essentially stands for something. Though The Maltese Falcon was the movie that made me fall for Bogie, over the years I've come to begrudgingly admit that The Big Sleep is the superior picture.

The plot of the film is anything but simple. Marlowe is hired by old man Sternwood (Charles Waldron) to take care of a blackmailer in possession of gambling notes owed by his youngest daughter, the petulant party girl Carmen (Martha Vickers). Turns out Carmen runs with a dangerous crowd, and on the first night of his trailing her, Marlowe ends up with two bodies on his hands and several more not long after. He also ends up trading barbs with Carmen's older sister, Vivian (Bacall). She's the one that Marlowe will fall in love with, and the one he hopes and prays isn't tangled up in this mess of gamblers, con artists, and wanton women any more than having a dizzy sister sitting in the middle of it.

Howard Hawks is a director who is as efficient as he is stylish. If there is anything that a visual storyteller should take away from his movies is his speed of delivery. There is hardly any time to pause for a breath in his best pictures. When he made His Girl Friday in 1940, he famously amped up the comedy by turning up the speed, instructing his actors to remove all the pauses after a line, for the first word of one bit of dialogue to come immediately on top of the punctuation of the preceding dialogue, resulting in two pages of script for every one minute of film, as opposed to the usual one-to-one ratio. He sticks to that kind of speed in The Big Sleep. It's particularly noticeable in the male/female dynamic, just as it was in Friday, though now it's Bogart and Bacall rather than Cary Grant and Rosalind Russell.

This keeps the story moving at a pace that keeps the audience as confused as the hero they are following, but since it's coming so rapidly, there's no time to pause and worry about it. Hawks and his writers expertly insert exposition throughout the movie, layering it naturally into the conversation so we don't realize we're playing catch-up. I also like how Marlowe moves his case along, usually by pretending to know more than he does and playing his hunches, letting his target's reaction confirm what he suspects. He can be rather playful and tricky about it. It's a trait that was even more obvious when Dick Powell played the snooper two years earlier in Murder, My Sweet, and a tactic I borrowed for Antonio Mercer in You Have Killed Me. Vivian asks Marlowe, "You like to play games, don't you?" In response, he smiles slyly and says he does.

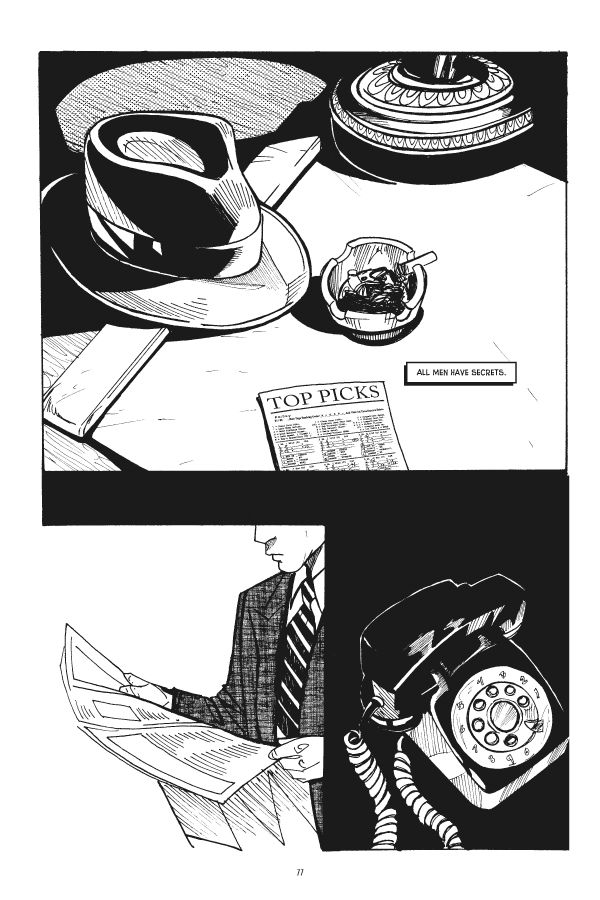

Outside of the dialogue, Hawks used his mis en scene to drop clues on his audience, to tease the confusion and evoke intrigue. He often did this by hiding details, by only showing part of the picture. Watch the scene outside the house of the effete bookseller, when the first murder happens, and look at the details that both the moviegoer and Marlowe are privy to, thanks to Hawks and editor Christian Nyby. A flash of light, a gunshot, a scream, a door opening, feet running by, a speeding car. We don't yet know anything, but we know someone was killed, a girl saw it, and someone else got away. It's a very quick scene, and you could isolate each element into a single comic book panel to achieve the same effect. The details are specific. It's obfuscation through precision.

Conversely, Antonioni's 1960 film L'avventura is precise in its obfuscation. It explores, but it avoids discovering. The object is to go through the motions of looking for the answers while trying to eventually create as much distance between you and them as possible--though, whether the characters know that or not is up to interpretation. At one point, the main male figure refuses to tell his new lover he loves her. Why? Because she already knows!

Here is the story: society girl Anna (Lea Massari), her fiancé Sandro (Gabriele Ferzetti), and her sister Claudia (Monica Vitti) go out on a daytime boat trip with their affluent friends to visit some rocky islands out in the middle of the ocean. When it comes time to leave--the visual/narrative symbolism: a shark sighting drove them out of the water and to shore, a weather change is forcing them back to the boat--Anna is nowhere to be found. Is she hiding? Did she fall off the cliff? Did she find another way off the island? There are no clues. Claudia knows that Anna and Sandro were fighting, so whatever measure her sister took, Claudia blames her future brother-in-law. Determined to prove his dedication, Sandro goes looking for Anna, and he eventually reconnects with Claudia. They follow some leads--a newspaper reporter points them to a druggist in a nearby town--but only end up in each other's arms. First Claudia denies Sandro, but she is drawn to him, perhaps drawn by the common bond of searching for Anna. Ultimately, though, she stops denying her desires, and as she does, not only does the search for the missing girl all but sputter out, but Claudia finds herself in her sister's same boring shoes.

I wanted to construct the dilemma of You Have Killed Me's missing debutante, Julie, to be like Antonioni's. Keeping the same two sisters device that both he and Chandler used, I had an older sister disappear from a locked bathroom. The younger sibling is in the bedroom outside of it, and to get out, Julie would conceivably have to pass Jennie. There are no other doors, no other windows, only a sheer cliff's drop to the ocean on the other side of the wall. Engaged just the way Anna was, about to be married, what made Julie run?

I was pretty conscious of the basic conceit I was lifting from Antonioni (who wrote the screenplay alongside Elio Bartolini and Tonino Guerra), but until I watched the movie again to write this column, I wasn't aware of how much the Italian filmmaker tapped in to the noirish tropes and how much I had really absorbed on my single viewing of the movie eight years ago. For a film that I've touted as one of my favorites, my memory of L'avventura was patchy, to say the least. For instance, I had no recollection of the overbearing father (Renzo Ricci) in L'avventura, and the conversation between he and Anna at the very start of the movie sets up a conflict that is similar to much of what is hinted at about Julie's past with the jilted detective, Antonio Mercer, in You Have Killed Me. Antonioni is establishing a conflict between old tradition and modernity, between the past generation and the present. Daddy wants Anna to marry someone that fits her station, Anna will marry Sandro just to spite him.

Because she clearly doesn't love him anymore. From what we see, Anna barely knows what she feels. As Antonioni sees them, people have become disconnected and out of touch with one another. Anna has cold feet, most likely because Sandro offers a marriage of convenience and a life that will trap her with its conformity. There is a scene where a distraught and lonely Claudia walks through an art gallery where baffled admirers look at abstract art. It appears to be leaping off the canvas, but yet confined by the square frame (not unlike a dynamic comic book panel). At the same time, the gallery building is crumbling and decomposing, and the stucco pattern on its walls could swallow the art into its own dying swirls if the barriers could be broken down. The threat of conformity is everywhere. Did Anna choose to run rather than be swallowed by it? Or did she choose the flux of the ocean, the ever-changing sea, as an escape? Is this the same choice Julie saw herself facing in You Have Killed Me?

There are signs of a certain age ending everywhere. The sisters talk of summer ending, inspired in this sad thinking, a rumination on carefree youth passing, by the shark that swims by, sniffing for blood. The encroaching modernity pops up again and again, often with a sexual or predatory guise, be it the foreign man who tries to trick the young girl on the train or the hungry pack of fellows making a spectacle out of a high-price hooker. Claudia will experience the same thing when left alone in one of the towns she and Sandro are searching, and she will also see the disrespect of lust up close when she meets the young artist who paints only nude pictures of women, and yet has no reverence for art. Anyone can pick up a brush, he says. Throughout, Antonioni uses motifs that suggest that his characters are at once pushing something old away and embracing something new, but that their eagerness to be free of puritanical restrictions has caused them to leap before they look. They are running to embrace new values, but they don't know what they are. There is a recurring image of Claudia closing a door on infidelity, first with Anna and Sandro and then with her friend (Dominique Blanchar) and the painter, and it's both her trying to keep these indiscretions a secret and to outrun them.

Antonioni also uses various touches straight out of crime stories to mark the path Claudia and Sandro are searching. Dishonest smugglers, disinterested police, rendezvous by train, and, of course, doppelgangers. The expensive prostitute looks like Anna, a more mature brunette to Claudia's younger-looking blonde. There is even some confusion with the druggist--was the girl he saw a blonde or brunette? A customer or his mistress? In addition to trying on her sister's boyfriend, Claudia tries out being her, wearing a shirt Anna gave her, and even once donning a brown wig. These sisterly entanglements are all basically variations on a theme, and though they may end up in different places, the Sternwood girls in The Big Sleep and the Roman girls in You Have Killed Me are all part of the same sorority.

The difference may be that in L'avventura, neither Anna nor Claudia is aggressor or victim, there is no crime or jealousy that passes between them, except for maybe a little early jealousy on Claudia's part. I suppose some argue that Anna gets out of Claudia's way and makes room for the romance, but Claudia might do better to interpret Anna's actions as a warning rather than opening any doors (the ones you keep closing, Claudia! Yeesh!). Once Sandro and Claudia fully embrace their passion, Claudia starts to regret it, starts to see that Sandro is just a man who goes through the motions. He laments that modern buildings aren't built to last--another case of where modern ideas are fleeting compared to the solid structures of yore--yet refuses to be an architect and design his own; instead, he prices out the ones others design. So, when Claudia wants to retreat to a new life, to stay indoors and avoid social obligation, Sandro returns to it, he doesn't change at all. Now that he changes his tactic and tells her he loves her, he's pretty much said the romance is dead. Claudia can choose to crawl in the casket with him, to accept the ennui and sadness, or she can follow Anna.

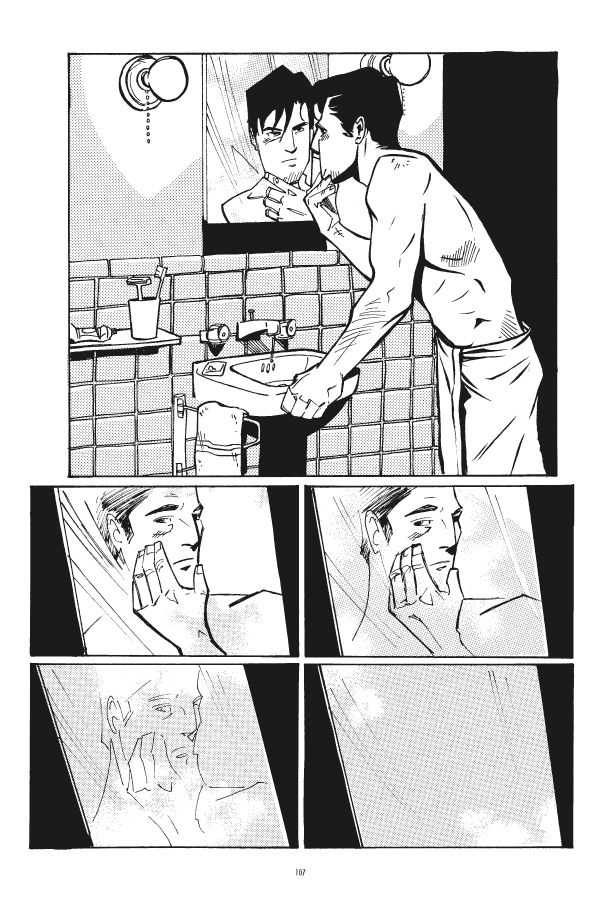

I made mention of how Howard Hawks and his editor used their cutting technique to tease out the information, to make scenes more exciting and heighten the mystery. Given that this is an article that is also comparing comics to film, I'd be remiss not to note that both directors would be nothing without their cinematographers, just as a comics writer would be nothing without his artist. In The Big Sleep, Hawks uses Sid Hickox's sense of shadow and his expert maneuvering of a confined place to create sinister scenes where the room often seemed to close in on the two people trapped inside it, leaving them alone with their secrets. On the flip, Aldo Scavarda creates a world for Antonioni that is expansive and alienating, gritty with its own detritus. The hallways of the estate at the end of L'avventura dwarf Claudia, and her smallness emphasizes her shame (compare the hotel hallways and spatial grounds Sacha Vierny shot for Alain Resnais a year later in Last Year at Marienbad; last year at Antonioni's?); when Scavarda moves away from these wide shots and in for a close-up, the effect is that the subject appears to be giant, once again emphasizing their singularity in a world that does not fit them. Both understand the variables of black-and-white, even if Hickox is more starkly defined and Scavarda is trying to smudge the very air into gray.

Joëlle Jones is my cinematographer for You Have Killed Me, and though I am fairly certain that she has never seen either The Big Sleep or L'avventura, she might find kindred spirits in both of their cameramen. Like them, she carves out space with an expert eye, whether it be the cramped basement where Mercer gets the daylights beat out of him or the wide shots of cliffside houses and racetracks, the scary hallways of abandoned hotels or the glitz of a jazz club. Her main tool is pure ink, and so she has more in common with Hickox's clearly defined shadows, but her use of tones gives her some of the ambiguity of Scavarda. The pattern on a man's suit, the sparkle of a woman's dress--these things smudge the lines between good and bad, ugly and beautiful, moral and immoral. That's why the auteur theory always breaks down, be it comics or cinema--unless you do it all exactly yourself, there is a shared vision at work. From the novel to the screen, through a director's suggestion and out a camera lens, off my script page to Joëlle's bristol board--it's all interconnected.